Stan has been following Apple (AAPL) for the past two years. It’s his most favourite stock in his portfolio. He loves the products and likes the company. He anticipates new product announcements with excitement and can’t wait to see consumer reaction. He has read several books on the history of the company, and he admires CEO Steve Jobs. Stan has most of his trading capital in AAPL. Although he has a strong passion for the company, you might say that Stan is a little over-attached.

He may have too much of his personal emotions wrapped up in the company, and it’s possible that these emotional attachments may overly influence his trading decisions. He has not only invested a lot of his money in the company but a lot of his personal time and effort. These financial and personal costs may lower his objectivity. When it comes to making decisions about trading the stock, it’s quite possible that he may be unduly influenced by what scholars call the “sunk cost effect.” It’s useful to be aware of this bias, and make sure that it doesn’t subconsciously influence your trading decisions.

The clearest examples of sunk cost effects are when we overpay for something, whether it is with money, effort, or time. The more you pay for something, the more you value it. For example, if you spend a year’s salary on a new car, you believe it’s worth what you paid for it. So when you try to trade it in a year later, and the trade-in value is a lot less than you think it should be, you feel a little upset. You may defiantly think, “How could it be worth less than what I owe? I think I’m getting ripped off.” You feel “cognitive dissonance.” That is, there is a logical inconsistency, or conflict, that requires resolution.

You paid a lot for the car, but now its value is less than you had thought. To resolve the uneasiness of the inconsistency, something in your psyche must change. You may think, “I’ll keep the car longer and get more value out of it.” But, even if you decide to trade it in, it’s hard to just write off the amount lost to depreciation. Humans have a natural aversion to loss of any kind, and that’s especially true when it comes to the market.

People tend to believe that an investment is worth what they paid for it. They believe that the original purchase price endures, even when current market prices suggest that the value has decreased. Sunk costs tend to increase when the value of the stock or commodity decreases. It’s hard to write off a loss, so when the value decreases substantially, it causes cognitive dissonance.

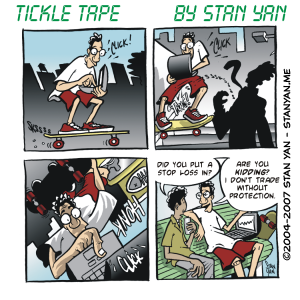

You think, “I paid $50 a share. I thought it would at least go up to $55, but now it’s down by 40%.” That’s logically inconsistent, so the easiest course of action is to believe, “I don’t care what the current price is. It is worth at least $50, so I’m going to wait for the price to recover.” Such a belief returns logical consistency to your psyche. That is the easy thing to do but not the most prudent. A losing trade rarely turns around, and all the hoping in the world isn’t going to make the price go back to the entry-level. One has to do the hard thing: Admit you were wrong, write off the loss, and close out the position. It’s hard to do.

When sunk costs are high, some traders may take on a fatalistic outlook. They may believe that since they have lost a large amount of money anyway, they have very little to lose by waiting to see what happens next. It’s like thinking, “I’ve lost so much already that I can’t lose much more.” Although such thinking makes one feel better about a losing trade, it’s dangerous psychologically.

One could lose the entire investment and experience excessive stress unnecessarily. There are real financial and psychological costs for refusing to ignore sunk costs. It is better to evaluate the potential of a trade based on what you can realistically make in the future and assume that you will not be able to recoup what you have lost. If you cannot see how the trade can turn itself around, cut your losses. By doing so, you will reduce your psychological and financial costs in the long run.

It’s useful to be aware of the ways the sunk cost effect may influence your trading decisions. Don’t let it get the best of you. Now that you are aware of it, you can identify this decision making bias. Don’t be afraid to cut your losses and move on.