11.1 – The origins of debt

Over the next couple of chapters, we will cover the basics of debt mutual funds. As you may recollect from the earlier chapters, there are about 16 debt mutual fund categories. I don’t intend to discuss all these categories of a mutual fund, because a typical investor does not need these many categories of debt investment. Instead, I’ll discuss the following which I think are essential –

- Liquid funds

- Overnight funds

- Ultrashort term funds

- Medium duration

- Dynamic bonds

- Corporate bond

- Credit Risk

- Banking & PSU

- GILT funds (2 different types)

In my opinion, this is a fairly exhaustive list and will cover many different investment situations which may arise. However, if you would like to know more about a category which isn’t discussed here, then please do post a comment and I’ll be happy to give you clarifications in the comment section.

The debt-oriented, liquid, and overnight funds together constitute nearly 50% of the 27 lakh crore assets under management (AUM) in the mutual fund industry (as of Jan 2020). So as you can imagine, this is a relatively large chunk of investor money. The debt funds play an essential role in the investor’s portfolio, and it serves a variety of purposes, including capital protection.

Before we understand how and when to use a debt fund, we need to understand a more fundamental concept, i.e. the origin of debt. To help you understand this, I’ll take the example of a simple debt structure, which I guess we all would have come across directly or indirectly in our daily lives.

So let’s get started. Assume you want to buy an apartment.

You do your research and shop around for the apartment with a checklist. After an exhaustive search, you eventually circle in on your dream apartment. The apartment comes with everything that you ever wanted – swimming pool, clubhouse, convention centre, supermarket, tennis court, and everything else desirable. The apartment costs you a sweet 1.5Cr, all-inclusive. You have 40L stashed away in your bank, which suffices as the down payment. You still need 1.1Cr to fund the property purchase. How will you source the additional fund?

Chances are, you will approach a bank and request for a loan. The bank evaluates your request and either give you a loan or denies the loan. Needless to say, before deciding to provide you with a loan, the bank will do a ton of background work and dig up every bit of information about you. One of the critical inputs for the bank is your credit score issued by agencies such as CIBIL or Experian. The credit score is a reflection of your creditworthiness, higher the rating the better it is for you and of course, a low credit score implies no loan or a loan at an exorbitant interest rate.

So let us just assume that you have a fantastic credit score and the bank decides to give you a loan of 1.1Cr against your apartment purchase. The details of your loan are as follows –

Credit score: 850

Amount : Rs.1,10,00,000/-

Tenure: 10 years or 120 months

Interest rate: 8.5%

Total interest payable : Rs.53,66,129/-

Total payable (Int + Principal) : Rs.1,63,66,129/-

Monthly EMI: Rs.1,36, 384/-

There are plenty of online calculators you can use to get these details. I’ve used the one available on Bajaj Finserv site. Of course, the credit score is arbitrary here 🙂

These details, along with a bunch of terms and conditions are printed on a document. A stamp paper is attached with stamp duty paid, and the document is registered. Finally, both the parties sign off. A document such as this is called a loan agreement.

Finally, the loan amount is credited from the bank to your bank account. The apartment will remain hypothecated to the bank till the entire loan amount is repaid. The hypothecation works as backup security for the bank. In case you refuse to repay the loan, the bank can sell your apartment and make good their principal and interest.

From the bank’s perspective, the loan is a ‘collateralised loan’, because the loan is secured against collateral, i.e. the property in this case. A collateralised loan is a safer bet for the bank as opposed to a non-collateralised loan.

At this point, I want you to recognise how a debt obligation is created. A debt obligation is created when a person needs to carry out an economic activity for which the fund requirement is far higher than what is available to him.

Going back to the apartment case, assuming things go smoothly, on every month, for the next ten years the borrower is expected to pay back a sum of, i.e. Rs.1,36, 384/- to the bank. The regular inflow to the bank is the ‘cash flow’.

So far, so good, this is a reasonably simple debt structure to understand. Let us now shift focus on the risk involved here. By risk, I mean the risk involved for the banker, i.e. the lender. What do you think can give the lender sleepless night?

There are a couple of things that can go wrong –

- Cashflow risk – The borrower can skip paying a couple of EMIs and make irregular repayments. Irregular repayments mean that the bank will take a hit on the expected cash flow, potentially leading to a chain of undesirable events

- Default risk – The borrower may get into an insolvent situation wherein servicing the loan becomes very difficult; hence the borrower decides not to repay. This is called ‘default’ or the ‘default risk’.

- Interest rate risk – The loan is given out at a specific interest rate. However, the economic situation may change, and the interest rates may drop in the future. This means that the bank will be forced to reduce the rates, and hence the expected cash flow takes a hit.

- Credit rating risk – The bank evaluates the borrower’s credit rating at the time of giving out the loan. At this point, the borrower’s credit rating could be excellent. However, for whatever reasons, the credit rating of the borrower can suddenly degrade, thereby increasing the chance of default risk.

- Asset risk – In case the borrower defaults, the bank has the right to sell the hypothecated property. What if the property itself loses its value? This is a double whammy situation for the lender or the bank. The bank loses both the principal and the asset.

These are the most common risk associated with a debt obligation. We have taken the example of a bank and an individual, the same can be extended to corporates as well.

Imagine a manufacturing company wants to build a new plant. The company needs about INR 800 Crores to commission this plant. How can they raise this money? There are two ways the company can raise this money –

- Approach a bank and seak a loan, pretty much like the apartment case we discussed

- Instead of a bank, the company can choose to raise a smaller amount of money from several people (investors). Say in multiples of 20Crs. The company, instead of paying interest to the bank, now pays the interest amount to multiple investors.

If the company takes the 1st approach and seeks a loan from the bank, then the binding agreement is called the ‘loan agreement’. On the other hand, if the company decides to raise this money from multiple investors (multiple lenders), then the binding agreement is called ‘bond’.

Think of a bond as a promissory note from the company to its investors/lenders promising to repay the principal amount at the end of the tenure and a periodic interest amount, also called a coupon.

I agree this is a rather crude and unconventional way to introduce the concept of ‘bond’ to you, but I hope you get the point. A bond is a debt product wherein the lender with surplus capital provides capital to the borrower who requires the capital. In exchange for the money, the borrower promises to pay interest (coupon payments) and repay the full principal at the end of the tenure.

As simple as that.

The risks that we discussed in the bank-apartment example applies to bonds as well. Three risks matter the most when it comes to the bonds –

- Credit risk

- Interest rate risk

- Price risk

At this point, if you’ve managed to understand what a bond is, the risk applicable (very briefly) then I suppose we are off to an excellent start to learn more about the debt funds.

Remember this though – debt funds and the functioning of debt funds is one thing and investing (or trading) the bond is another thing. You as mutual fund investors should only be concerned about three things –

- When to invest in a debt fund and how to choose one?

- What a particular category of debt fund does

- The risk associated with that category of debt fund

The fund manager of the debt fund should be concerned about investing or trading in the bond market.

The bond market is a reasonably big market, not just in India but across the world. Companies often issue bonds to full fill their capital requirements and these bonds are subscribed by the investors.

The mutual fund companies which have the capital subscribe to bonds issued by the companies which have a capital requirement.

With this background, let’s start discussing the different categories of debt funds.

11.2 – The liquid fund

The liquid fund is perhaps the most popular debt fund within the debt fund universe. A liquid fund makes investments in debt products which have a maximum maturity of up to 91 days.

In simple words, the liquid fund invests in debt obligations, wherein the borrower promises to repay the borrowed money (principal) within 91 days (maturity) of such borrowing.

Here is a typical example – Power Finance Corporation (PFC) of India needs 150 Crs to fund its working capital requirement. They agree to repay the borrowed amount to the lender within 50 days. PFC agrees to pay 8.5% interest (also referred to as the coupon) against this borrowing.

HDFC AMC has 150Cr to invest; they see this as an excellent opportunity to earn 8.5% interest; hence they give the funds to PFC.

The deal is done.

After 50 days, PFC repays 150Cr to HDFC AMC along with 8.5% interest.

Note, when any interest or coupon rate is quoted, it is quoted on an annual basis. So this is 8.5% for the 365 days. For 50 days, interest on a pro-rata basis is –

= (50 * 8.5%)/365

= 1.164%

So HDFC AMC will get back 150 Cr + 1.746Cr back from PFC.

I suppose this is a relatively simple deal to understand.

Like I mentioned earlier, a liquid fund by regulation can invest in debt which has a maximum maturity of 91 days. When a corporate entity borrows for such short term basis, they do so by issuing something called as a ‘commercial paper’ or CPs. In the arbitrary PFC example I used, PFC is deemed to have issued a 50 day CP, which was subscribed by HDFC AMC.

The Government too borrows on a short term basis to fund its short term financial needs. However, when the Government borrows, it does not issue a CP but instead issues a treasury bill. The Government has three variants of t-bills –

- 91-day T-Bills, the maturity of 91 days

- 182-day T-Bill, the maturity of 182 days

- 365 day T-bills, the maturity of 364 days

You can read more about the treasury bills or the T-Bills here.

Now, place yourself as a lender, someone with surplus capital. You are looking for an opportunity to invest 100 Crs. There are two possible borrowers, both wanting 100Crs each –

- A sugar manufacturer willing to offer 6.5% coupon

- The Govt of India provides a 6.5% coupon

Whom would you lend? This is a no brainer; you’d give to the Govt because you know that with the Government, there is no credit risk. The Govt will repay, but the same cannot be said about the sugar manufacturer.

Does this mean that the sugar manufacturer will never get the required funds? Yes, as long as the sugar manufacturer offers a coupon equivalent to the Govt, it will be hard for them to source the fund. The lender will lend if he is compensated for credit risk; hence the coupon has to be higher than the equivalent T-bill.

So in this case, the sugar manufacturer should offer say 7 or 8%.

Let’s extend this thought. Assume there are two sugar manufacturing companies –

- Company A with an impeccable track record. It is in business for 25 years, profitable, and steady cash flows.

- Company B, five years of operations, breaking even, backed by young entrepreneurs.

Both need 100 Crs. Both offer 8%, you have the money, whom would you lend?

Company A, of course, because company A has a better financial history, hence lesser probability of default.

Does that mean, Company B will never get the funds? Of course, they will, as long as they compensate the lender for the additional credit risk. Hence company B has to offer something like 10 of 11%.

The credit rating reveals the credit risk of a company. The credit rating of a company is equivalent to an individual’s CIBIL score. The higher, the better, which also means companies with higher credit rating can borrow money by offering lower coupons.

In its portfolio, the liquid fund contains several CPs and T bills, while T bills are relatively safer, CPs aren’t.

This leads me to the most critical point about liquid funds.

11.3 – Why liquid fund?

People invest in liquid funds to park cash, which they intend to use sometime soon. By ‘sometime soon’, I mean within a year or at the most within a year and a half. The purpose of this investment is to protect the capital, use it in its entirety for the purpose planned. So think about the liquid fund as a parking space for your excess funds.

Question is – why to invest in a liquid fund and why not let it be in a bank’s savings account. Well, people opt to invest in a liquid fund because the liquid fund offers a slightly higher return compared to the bank’s savings account.

The problem, however, is the fact that the liquid fund is often pitched as a better than a savings account (SA) or the fixed deposit (FD)’. This is not true at all. A liquid fund may offer higher than SA/FD account, but also comes with a certain amount of risk.

To put this in perspective, an average SB account rate as of today (Feb 2020) is 3.5% to 4% whereas the average Liquid fund gives you a 6% return.

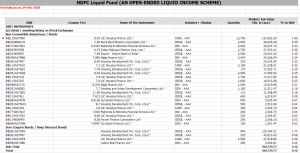

However, the liquid funds consist of several CPs, which are suspectable to credit risk. Here is the snapshot of HDFC’s Liquid funds –

As you can see, HDFC Liquid Funds has several CPs its portfolio. Of course, the credit ratings of the issuer of these CPs are all good, but then things change quickly in the markets. A downgrade in the issuer’s credit rating means a steep cut in the NAV of the liquid fund.

HDFC’s portfolio also has Government securities, which virtual consists of no credit risk, thanks to the implicit sovereign guarantee.

While this is a good liquid fund, it is still not risk-free, you can lose your money if something were to go wrong, which is not the case with a SA or FD.

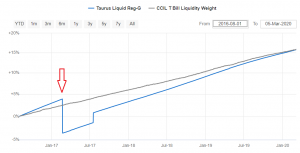

To give you a perspective of how bad things can go, check this –

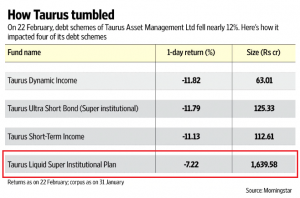

This is the NAV graph of Taurus AMC’s Liquid fund. The NAV fell close to 7% on a single day in Feb 2017. All gains were wiped off, and in fact, the investors took a hit on their investment capital. It took almost a year for the fund to recover back to its previous levels.

The reason for this fall was that Taurus had nearly 2000Cr of CPs issued by Ballarpur Industries. The credit rating agencies downgraded Ballarpur’s CPs, and that translated into a 7% vertical fall in NAV.

Anyway, I’d suggest you read this news article, and I think it puts all the discussion we have had till now in some perspective.

So if you are investing in Liquid funds, you need to be aware of a few things –

- Invest only to park your spare cash

- Expect a return slightly higher to your SA account

- Liquid fund is not risk-free, you can lose money when you invest in it

- Choose a fund which has relatively less default risk – meaning the liquid fund portfolio should have a higher concentration of Government securities.

I’ll stop this chapter here. In the next chapter, I’ll discuss the close cousin of the liquid fund, i.e. the ultra short term fund.

Stay tuned.

Key takeaways from this chapter

- When a corporate entity borrows funds (for more than one year), they do so by issuing bonds

- Corporate borrowings for less than a year are done via the issuance of a commercial paper or the CPs

- When the Government borrows, they do so by issuing a treasury bill or the T-Bill

- Against the borrowing, the borrower pays interest (coupon) to the lender

- The lender faces multiple risks when lending funds to the borrower

- Credit risk and interest rate risk is the primary risk for the lender

- Liquid funds can invest in CPs, T-bills, G-Secs, SDLs, and corporate bonds, as long as the residual maturity of the instruments is less than 91 days

- A liquid fund is not a proxy for a savings bank account; it carries credit risk.

This is the NAV graph of Taurus AMC’s Liquid fund. The NAV fell close to 7% on a single day in Feb 2017. All gains were wiped off, and in fact, the investors took a hit on their investment capital. It took almost a year for the fund to recover back to its previous levels.

The reason for this fall was that Taurus had nearly 2000Cr of CPs issued by Ballarpur Industries. The credit rating agencies downgraded Ballarpur’s CPs, and that translated into a 7% vertical fall in NAV.

How exactly does the math\’s work here. I don\’t get how Credit rating fall relates to decline in NAV. Pleas elaborate

Credit rating is an indicator of the probability of a default. The higher the probability, the higher the fall in NAV. This is based on perception, not really math.

Got it but how to quantify the fall, like who has the authority to decide how much variation in NAV should be there

Ah, that is anybody\’s guess right?

I have the same question. Thinking a bit more, i am still not clear.

Taurus Liquid fund\’s NAV is based on the CPs issued by Ballarpur. Agenencies rating Ballarpur down wouldn\’t mean, Ballarpur will default right? Unless Taurus liquid fund invested in the equities of Ballarpur and when someone rates Ballarpur down, Ballarpur price goes down causing a problem to the fund. Did Ballarpur default on the same day – i.e., on the day when their ratings went down?

I dont recollect fully, but as far as I they they did default.

Under the sub heading \”11.3 – Why liquid fund?\” in the last line;

However, the liquid funds consist of several CPs, which are suspectable to credit risk.

In that line the word \”suspectable\” is wrong as there\’s no word like that, the right word is \”susceptible\”. I know it might be a spelling mistake but just pointing out so that you can correct it. Thanks for the easy to understand content with explanations and definitions.

Thanks so much for pointing that out, will fix that 🙂

Can we park funds in debt funds and pledge them to buy stock in delivery in the cash market?

Yeah, but please do call the support desk once.

MARGIN TRADING FACILITY FOR LIQUIDCASE. Is there any working model that can be thought about for Zerodha users.

Users like me would be happy to take this facility(MTF) to buy Liquidcase, Pledge and trade safely in option.

6.5-7% return from Liquidcase.

8% return from Option will get us to Breakeven ( to pay 15% for MTF)

Anything more than 8% from Option Trading would go to user\’s kitty.

Can you pls throw some of your thought on this.

Regards.

Ah, I\’ve not thought through this. But that said, there is nothing like \’trade safely in option\’, 🙂

Thanks Karthik, super happy that you responded to my last question. I have another question. I have gone through all the great content that you have created but I miss content on exit strategy. I understand long-term and goal based investing approach. But how one should react to free falling market in case of major financial crisis lasting several years. When one should pull emergency break in free falling situations or one should not? Another related question to above described situation: If I see market wont be recovering any time soon, does it make sense pull out my investments to collect good returns I have made so far and then may be reinvestment principal amount back may be after few months or year in case of falling market. Does this make any sense at all?

If you have clarity that its a free falling market that will go on for several months, then you should probably exit the earliest you have this realization. The sooner the better. Move all the funds to safer assets. But the tricky bit is – how do you even figure this? Things like 2009 sub prime crisis also lasted just 1 year. So it is very hard to figure this in the first place.

Hi Karthik, I am an NRI so I have an option to invest in NRI FD which gives me tax free and risk free returns of 7-7.5%. So am I better of investing my debt portion (for diversification purpose) in NRI FD instead of Debt Mutual Fund? So far, debt MF doesnt make too much sense to me in my case even though I eventually plan to return to India. Am I missing something here? Am I diversified enough by investing my Debt portion in NRI FD as long as I have this option?

Gaurav, for this I\’d suggest you speak to a qualified RIA to check if this is indeed the best alternative, don\’t think I can advice you on this 🙂

But that said, 7.5% tax free is a great return for a debt product.

Hi Karthick Sir,

Golden Pi is the platform by Zerodha we can Invest directly into Debt instruments without the help of Mutual Funds

Yeah, but it is not a Zerodha platform, it is an independent company.

can you explain bit about ESG Funds and How it is different from Nomral funds

Here you go – https://mf.nipponindiaim.com/mutual-fund-articles/esg-(environmental-social-governance)-funds

Thank you Karthick Sir,

Give some examples of how much the ticket size will be. Is the ticket kind of lot size like an IPO? How much does the retail investor need a minimum amount to invest in corporate bonds when it is trading secondary or primary?

No, there is no ticket size as such, but there is a minimum investment in each fund. Something like 500 or 1000 based on each fund.

Hi Karthick Sir,

I just want to know that Individuals can\’t invest in individual debt issued by the company

For example: If Reliance issues bonds, as an Individual is that possible for me to invest directly in bond else I need to invest only Via debt fund?

If Retail Investor like me with 15,000 as an investment can\’t invest in corporate debt can you explain why?

Retailers can invest, there is no issue with it. Its just that the ticket size for these corporate bonds is quite high and hence most retailers dont invest in them and would prefer investing via a debt fund.

How will I receive the coupon payments on debt? It is reinvested or paid out every month/ quarter/annually?

There are no coupon payments in a debt funds, Ananya.

It\’s really helpful 🙂

Happy learning.

Suppose I invest in Liquid fund on day 1 and I need this money after 1 year. Such liquid fund invests in 91 days Commercial paper. So will I receive my money in 91 days or I will receive it upon selling the units of Liquid Fund?

If I receive on selling the units, then is it possible that I keep my money invested for more than 2 years?

In how many days will I receive my money on selling the units T+2 days or T+1 days?

Yes, you can as the money you invest is in the fund, which in turns invests in a liquid fund. As far as you are concerned, its a fund. So you can invest and withdraw anytime.

Hello Karthik,

I wanted to express my gratitude for the dedication you\’re putting into Varsity – it\’s truly commendable.

Could you please develop educational modules about Hybrid funds? Specifically, I\’m interested in learning about Balanced Advantage Funds, Dynamic Asset Allocation Funds, and Multi-Asset Allocation Funds.

I\’ve already invested in Indian equities and now I\’m looking to venture into Debt investments for better asset allocation. I have a couple of questions:

Given that the indexation benefit is no longer applicable to Debt Mutual Funds, would it be a prudent choice to go for hybrid funds or stick with debt-only funds?

I understand that investing in hybrid funds also exposes me to equity-related risks. Since the decision of allocating between equity and debt lies with the fund manager, how can I make well-informed choices in the hybrid category?

Considering that retail investors often have limited funds to invest, diversifying into numerous funds might not be feasible.

I\’m eagerly anticipating your response. Thank you for your continued efforts in contributing to Varsity and Zerodha\’s success. Keep up the fantastic work!

Best regards,

Nithin

Thanks Nithin, will surely add content on this. Yes, hybrids are a decent option and you should explore this, especially in the context of no idexation benefits.

Sir,

You have stated-“Interest rates and bond price are inversely proportional. If the interest rates increase, the bond price reduces and vice versa.”

With the above understanding, can the below be concluded?

(i) If the RBI increases interest rate, and a person is able to capture the bond price in the secondary market with lesser price then does that imply a person will earn more benefit/yield at maturity?

Yes, based the interest rate movements, fund managers do buy and sell bonds to profit from capital appreciation.

Sir,

You have stated-\”Interest rates and bond price are inversely proportional. If the interest rates increase, the bond price reduces and vice versa.\”

With the above understanding, can the below be concluded?

(i) If the RBI increases interest rate, then the bond price in the trading market decreses which means a person will earn more benefit/yield at maturity?

Sir,

You have stated-\”The yield of a bond and the price of the bond are inversely proportional. If the price of the bond increases, the yield of the bond decreases and vice versa.\”

Does it mean that if one manages the buy a bond in secondary market at a lower price than the launching price of the bond, then he manages to get more benfit at maturity?

Yes, this is like capital appreciation in Equity markets.

Sir,

Are the MF debt instruments open ended means can the retailers close any scheme at any time?

Yes, they can.

Sir,

Under ultra short funds, you have cited an example with investments for \”Money market investments\”, \”Bonds & NCDs\” and \”TREPS\”.

(i) TREP also falls under a particular type of bond baering 1 day validity. Correct?

(ii) Are this \”Money market investments\” also referring to several types of bonds only?

1) Yes

2) Mainly TREPS

Sir,

Suppose due to some discrepancy the crdit rating or demand for a particular bond decreases. The bond was primarlily floated from the company for Rs. 100/-. With this demand fall, will it like the bond value now decrease to Rs. 80/-. Since, I don\’t possess any undrstanding on bond markets/trading, could you please help here to understand?

This is possible. You need to figure out the factors that drag down the value of a bond, just like the ones that drag the value of equities down. Once you do, understanding bonds become easier.

Sir,

Do the AMCs publishes each day NAV of its different schemes? How can retailers then decide which schemes to invest?

Yup, they do. But the decision to invest in debt funds or MF funds in general is not based on NAVs, its more about other aspects, that we have spoken about in details in this videos.

Sir,

Like in equity MF, someone has the option to pay as little as 500. Is there any concept of such in debt MF also? can someone invest in SIP and lumsum?

Yes, each fund has different least minimum that you can invest in.

Sir,

You suggested to park money in Liquid funds foe a period of more than 3 months and in overnight funds for less than 3 months. Now, liquid funds have a maturity period of 91 days while for overnight funds have maturity for 1 day. Suppose, I have some surplus cash and want to park for more than 3 months and I invest Rs. 100 in an AMC\’s overnight debt fund scheme. Please let me know if I am correct on the below understanding.

(i) The fund manager decides the proportion of Rs. 100 and segregates into different schemes of 91 days. He will have to buy schemes frm secondary market in trading platform at the time I invest the money at different prices than the primary launch price. Is it correct?

(ii) He may find an opportunity to buy a debt instrument in primary market if my timing of investment matches with floating of a debt instrument of a company and the AMC wants to buy that floating.Is it correct?

(iii) Suppose I want to withdraw the scheme after say 5 months. I shall receive the amount based on the portfolio price of all the debt instruments the fund manager investment at that moment. Is it correct?

1) There is an overall fund structure that the fund manages, which makes it smooth for investors. You don\’t really have to worry about the 91 day thing when investing in liquid funds, the fund structure takes care of it.

2) Yeah, they do keep an eye on the primary market to spot these opportunities

3) Yup

Sir,

I got stuck when came to Ultrashort term debt funds. I am unable to make the dots connected. Equity was too easy to understand but debt fund seems a little tricky.Since, I don\’t have understanding on how trading goes with debt instruments, I feel that may be one cause for this. Meanwhile, could you please help to understand on the below?

We understood that a debt is such an instrument which pays regular interest and pays the principal at the end of the tenure. In that understanding, how can a scheme under a debt category bears risk. Like the one you cited with an example with Tarus ivestment with Ballarpur industries. With credit rating goes down for Ballarpur, the NAV of all the funds of the AMC which have investment in Ballarpur goes down.

(i) Now, suppose Tauraus has invested in Ballarpur for a bond of Rs. 10 and for some reason the credit goes down to the Ballarpur. But they have not yet defaulted yet to give the real shock. Is it then like in the trading market the Ballarpur has reduced its value (say Rs.8) just like the equity market and that carries the sense of the risk?

The debt papers get traded in the bond market and the value of these bonds keeps changing based on the creditworthiness of these bonds. The same factors that impact equity kind of impact debt as well. So yeah, if a bond falls from 10 to 8, then that is a mark to market loss for debt fund managers holding these bonds.

Sir I don\’t have any idea about loans. Could you tell me how did the figure Rs.53,66,129 come up with 8.5% interest for a principle of 1.1 Cr. Thanks.

Thats the amount the company would have raised, mentioned in the document.

I am new to investing and maybe missing something in article or my understanding . What I understand is that bond funds invest in CPs and T-Bills, and give you returns based on the promised interest rates by corporates/government schemes. What I am not able to comprehend is , how reducing the rating of Taurus effected NAV ?

CPs are issued by corporates. So if an MF invested in a CP of a company and the company shows signs of weakness in financials (risk of default increases), then the ratings will get impacted.

Just a typo on the page.

To find, please use ctrl + f and search for the word \’seak\’

Will fix, thanks 🙂

Please add the categories: money market fund and corporate bond fund too.

Noted.

can liquid funds go down from there previous close NAV on a day to day basis.

if yes then is it the natural demand and supply which effects the price of the NAV or something else

It should not. But sometimes they do due to change in interest rates.

Dear Sir,

why liquid fund has so much aum?Does liquid fund Aum size matter?

Hmm, not so much. AUM is high because lots of corporates park cash in liquid funds.

Hi Karthik,

Love all the structured chapters.

At the risk of sounding stupid, I wanted to ask – based on my understanding from the above learning, A liquid fund is a scheme that makes investments in instruments having a maturity of up to 91 days and itself has a Macaulay\’s duration of 91 days, does this mean the scheme will also mature in 90 days? If, no. How will the AMC reinvest my money when it has to credit my bank regularly with interest amount and principal by the end of 90 days? Asking this because Axis Liquid fund was showing the returns (if invested) for the last 1-4 years in the performance section of their site.

Jai Ailani

Jain, so the AMCs keeps rotating the funds between 91 and 180-day bills, so they are constantly invested. There is no maturity for the fund as such and works on a continuous basis.

Thanks. Understood.

I never realized there is anything such as flexible interest loans.

Yup its there. Helpful for folks who have a view on interest rates.

Thank you, Karthik. I was half-joking about financial mentorship. I already know how busy you are with the Zerodha Varsity and helping other people too here in the comment section, not just me. Reading Varsity and discussion with you in the comment section has already taught me a lot 🙂

I am still a beginner in investing world. I will see how my portfolio goes over the next 1-3 years and then adjust the ratios.

Regarding the personal loan example, you said if the interest rate reduce in next year, the bank will be forced to reduce interest rate for my existing loan.

It is still not clear to me. Why do they have to do it if we already have a fixed agreement? If the interest rate increase, will the bank force me to pay an even higher interest rate?

Or do you mean to say that the statement only applies to the new loan and not the existing ones?

For a personal loan, it may not affect much as these are short term loans. But for a long term loan (or a long term bond), it does. Like a housing loan. Loans are either flexible interest or fixed, most prefer a flexible interest to benefit from their view of declining interest rate. Here is an article – https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/07/fixed-variable.asp

Hi Karthik,

First of all, thank you for the welcome. I am quite surprised that you remembered me considering you probably get 1000s of queries from tons of people here. 🙂

It\’s been an incredible journey during the last 1.5-2 years. I started as a day-trader -> options trader -> momentum trader. And now I am creating my own long-term portfolio. I had to give up on day/options trading after 5-6 months because I was making 10x more money in my full-time job while having 10x less stress and ~0 risk. Day trading was very exhausting mentally too. I think in a way, I am learning the age-old wisdom at my own speed.

I am currently 50% invested in US stocks, Indian stocks, Crypto, Tech ETFs like NDX, SOX, and so on. I make good money in my job and have 0 dependents so I think I can afford to have a high risk for a 50% portfolio.

I think my portfolio is very volatile already so I want to play it very safer with 50% of my remaining capital. I\’ve been planning to learn more about the debt funds to decide if it\’s what I want. I don\’t want to chase returns and they don\’t seem very safe. So I guess I am good with FD.

I think I have completed 11 modules now so far (I skipped some chapters in modules 3,9 and 10 through which were above my head). Every time someone asks me for resources, I always tell about this book and always mention that you are very active in the comment section 🙂

I think we are also connected on LinkedIn. I would love to have you as a financial mentor but I guess you probably already have too much on your plate.

Anyway back to the question.

Question 1:

> Interest rate risk – The loan is given out at a specific interest rate. However, the economic situation may change, and the interest rates may drop in the future. This means that the bank will be forced to reduce the rates, and hence the expected cash flow takes a hit.

You said that in this post. I have never taken a loan so I don\’t know for sure. But isn\’t the loan interest locked for the tenure?

Question 2:

I assume these interest rates, credit ratings affect bonds price if you trade them like a stock trader. But, If you invest in govt security for 10 years and don\’t exit mid-way, you are going to get the coupon amount mentioned while purchasing. Even if rating or national interest rate changes your bond returns will be locked like an FD if you hold it till maturity (assuming there is no default)?

Hey Varun, happy to learn about your progress. I think you are headed in the right direction with respect to your portfolio split, wishing you the best of luck with that. About the financial mentor bit, that won\’t be possible given the workload, but I\’m always here and will reply to all your queries 🙂

Q1 – Interest rate in an economy is a function of many variables. As the economic conditions change, so does the interest rates. For example, if the inflation increases, interest rates in the economy decrease, so yes, interest rates changes making the loan cheaper or expensive over time.

Q2 – Yes, that\’s correct. YOu buy a Govt Security and sit on it for 10 years, you will continue to get the promised coupon, unless the Govt itself is at the risk of defaulting on their obligation. We have seen this happening in the past (Venezuela, Argentina, Indonesia).

How can I invest in a debt fund through my Zerodha app? Help please.

You can invest via Coin, our mutual fund platform – https://coin.zerodha.com/

Same with \”Asset risk\” in previous comment. We had a deal and we are going to stick with it.

Note: I am not talking as a trader of bonds. I am talking as someone who is going to hold it till maturity.

As long as there was no default, I should get my 10% interest? Why did my bond returns changed just because credit rating changed. I should still get 10% interest (assuming there is no default)

Hope my previous reply answers your query.

Hello Karthik,

I don\’t understand why credit rating or interest rate affects bonds or even loans.

Suppose I have a contract with someone and I gave them 1L on 10% interest for each year.

Now their credit rating changed over the years, but they paid me 10% interest annually without any default. So why did the bond/loan value change?

Same with interest rate. We had a deal of 10%. Now whether the T-Bill increase or decrease, why does it affects our deal?

Varun, welcome back! Seeing a query from you after a long time 🙂

Credit rating agencies rate the debt paper to indicate the likelihood of default. Yes, you will receive your money for this payment cycle, but what is the guarantee that you will receive for the next? That\’s what these guys rate and the price of the bond is dependent on the rating.

The images are not clear in the downloaded PDF

Let me check, Maaiz.

Sir

If CP is break by the corporate saying it can\’t return the interest also the principal. Than do we get any asset of the corporate so we camln sell and atleast generate the principal

Yes, debt holders have a claim over the company\’s assets in case of a default.

Hi, can you please explain why it took a year for Taurus AMC liquid fund to recover back to its previous levels, considering CPs in liquid funds have a max maturity of 91 days. If there was just a rating downgrade (and no default), shouldn\’t the fund be out of the bad exposure as soon as the CPs expired?

Please do check the portfolio, maybe there was a paper that went off.

The 3rd variant of T-Bill should be 364 days instead of the mentioned 365 days.

Checking this.

Sir these CPs,T-bill,bonds are the government securities?

Or all these things are debentures?

Gsec and T Bills are, CPs can be of corporates.

Hello Karthik,

If I need to redeem the amount from, liquid fund what is the cut-off time for NAV applicability?

and

How many days it might take to credit the amount to my account if I redeem liquid fund as I am planning to put some amount of Emergency corpus in it.?

T+2, Seetaram.

Hello Kartik,

I am eager to know about interest calculation on loan amount. What is the formula for interest calculation?

Please look for an EMI calculator online.

Hi Karthik,

After doing a lot of research, still am not able to conclude on FD vs Debt Funds.

Apart from taxation benefit (that too for long term), I dont see any reason for debt fund if we have auto-sweep option in FD or we have FD of Small finance banks and other banks which are covered for 5 lakh insurance. Why to enter such an asset whn there is a risk element and as you mentioned capital protection is our aim and not returns. Liquidity I already have in auto-sweep accounts.

Returns are higher if you start looking at longer duration funds and funds with higher credit risk. But then, this cannot be compared to an FD return as the risk profile is different.

Sir,

After the downgrading by credit rating agency the NAV falls. But what happens to NAV if the company pays the Principal and intrest without default? Also what action will the AMC take against the company if it defaults?

That will increase their ratings for other bonds.

Dear Sir,

SGB comes under liquid funds?

I had pledged SBGs in my zerodha demat account and collateral showing under liquidbees collateral?

I did not know that SGB are cash equivalent as they r not liquid enough.

Hi Karthik,

Was going through some of the funds under Short Term Debt category and observed many of them had GOI bonds with maturity year to be 2030, 2027 or so and if the short term debt fund needs to have maturity to be between 1-3 years, does that mean that funds can infact have bonds with maturity greater than 3 years but still maintain the average maturity requirement ? or is it like all the bonds in the fund have to mature within 3 years ?

On an overall basis, they need to have a maturity between 1-3 basis. But there could be few funds that are slightly higher maturity.

Sir,

In the HDFC AMC & PFC example, what formula is used to calculate the interest on pro-rata basis? This may sound naive, but I want to get my concepts right.

BTW very lucid explanation and so relatable with real life examples. Thank you for all the effort!

Lakshmi, the formula is – Number of days interest is applicable * interest rate / Number of days in a year.

Hello sir, loved the way you teach each and every concept! I had a doubt how will reduction in the ratings of the bonds by rating agencies will reduce the fund\’s NAV, Even if the ratings are reduced it will indicate falling of credit worthiness which will eventually lead to formation of new bonds with higher coupon rates right? And the company may also have paid the interest to its lenders so how did the fund\’s NAV went down?

It\’s a perceived risk. If the credit ratings are downgraded for a fall, then the fear of the company defaulting on the bond increases, which means the price of the bonds increases, which in turn decreases the yield on the bond, hence lower NAV.

Yeah. Systematic Withdrawable Plan is clearly an advantage of Liquid Funds.

Just FYI, I just finished \”Module 3 – Fundamental Analysis\” and now in the middle of \”Module 11 – Personal Finance\”, I must say the content is really awesome and understandable and to-the-point. Learnt many things on the go, as well as your content answered a lot of my concerns.

Thanks Karthik 🙂

Ritesh, thanks for letting me know. Happy to note this. Hope you continue to enjoy reading and learning from Varsity 🙂

Karthik,

Considering an investment horizon of 1-3 years AND considering the safety of fixed deposit amount which is guaranteed up to 5L per bank OR 100% guarantee in Post Office Term Deposit,

As both the instruments are liquidable, why would an investor choose LIQUID FUNDS or any other debt fund for that matter over a FIXED DEPOSIT, if returns are similar?

It should not really make a difference. One advantage is where you can park funds in a liquid fund and withdraw regularly to invest in another fund.

Hi Karthik,

I learnt that the returns (interest rate) of liquid funds are higher / slightly better than the savings account\’s interest rate. I agree.

Keeping the risk and tax factors aside,

1. What\’s your thought on Liquid Fund vs Fixed deposit?

2. Whose returns would be higher for the 3/6/9/12/18 months period?

3. Which instrument would you advise to opt for, for the aforementioned time frames, liquid fund or fixed deposits?

I think the returns are similar, Ritesh.

Any plans of writing a module on real estate investing? 😀

Not really 🙂

Hi Karthik,

Asking this for my understanding. You mentioned NAV will drop if one of the CP in liquid fund ending up in non repayable due to default credit risk. But that is helping NAV to drop is because that whatever the AMC liquid fund invested in that CP is not going to get back its principal ? Is that the right reason ? is there any other reason for drop in NAV if the company defaults credit risk ?

That\’s right, Ashok.

Is it possible i can take N number of liquid funds with N number of AMC company with small amount of investment in all of them and whenever required can withdraw money from any one.

Sure, you can. But why would you want to do that?

Was looking for further clarification on this: why did the NAV decrease with the fall of credit rating of Ballarpur Industries? They did not default in paying back to Taurus I guess.

Bond prices are sensitive to the probability of default along with the actual default. So when a downgrade happens, the probability increases, hence the bond price decreases.

Hi Karthik, why all the modules available in varsity website are not available in varsity app?

We will update in a month\’s time.

Hello Karthik,

Thanks for the nice article.

I had invested in the \”Indiabulls-ultra-short-term-fund\” through the coin, but now Zerodha is saying this fund is no longer active and can not be redeemed. I didn\’t find any information in AMCs official website.

I could sem fund\’s AUM is increasing every month from 1783 in November to 1794 in January. How can closed fund\’s AUM increase, I could notice all its investment is in TREPs CCIL. Can you share more details on what\’s CCIL?

Checking on this, have passed your email ID to the team and they will respond to you on this.

Sir, have gone through the entire module. Have one doubt- What\’s the benefit of going with Debt funds over FD, since debt funds are riskier then FD and gives the same return in current scenario. What are your views, should we invest in FD or Debt fund ?

Debt funds have an advantage in terms of taxation and also offers liquidity. These are the two big advantages of a debt fund over FD.

Hi,

I couldn\’t quite understand the risk in CP. Suppose , I purchased some CP offered by a company and due to any reason that company defaulted then , in such cases aren\’t there any legal ways by which I can get my money ? Like a share holder gets from company properties etc?

No, if the company files for bankruptcy and defaults, there is nothing much you can do.

k sir, will check it out.

What to look in their portfolio profile sir, sector wise risk or company wise risk? Or any other things sir? Because I saw that all the CP and CD has good ratings.

The next chapter (will upload by mid next week) is about this topic, hopefully that will answer most of your queries.

I checked HDFC, ICICI and SBI liquid funds sir, all the three has more than 50% government bonds, so how to filter further and select one among the three?

They all are similar in terms of returns. Look for the detailed portfolio profile.

Do AMC\’s collect collateral against the money lended to companies ?

Collateral is usually wrt to the bonds they hold.

How does downgrading of credit rating translate into losing NAV? Can you elaborate?

Lower credit rating indicates the possibility of a default, which is not really great news for the bonds. Traders dump the bond, driving the price lower and hence the NAV takes a hit.

k thanks.

I am trying to allocate my trading money between funds for pledging sir, I listened to DSP liquid ETF video, so there it was explained that they invest through TREPS, so I concluded that liquidbees and liquidETF are like overnight funds. So the risk and returns of overnight fund and liquidbees will be the same. Is my understanding correct sir?

They are slightly different Mani. Overnight funds have securities with overnight maturity, whereas liquid funds have maturities ranging from 90-365 days.

Also I have one more question sir, where can one fund HDFC liquid fund holdings sir?

https://www.hdfcfund.com/our-products/hdfc-liquid-fund – downloads section doesn\’t have that information.

Look for the fact sheet Mani.

Sir, in which category liquidbees fall into? is it overnight debt fund?

Liquid fund is a separate category on its own.

Hi Karthik,

A fantastic module once again as I am binge reading a lot.

Could you shed some light on how a reduction in the credit rating of Ballarpur translated to a decline in NAV of Tauras AMC?

Had this been an equity, i.e a company listed on stock market, a decline in their credit rating would have led to a bearish market sentiment which would mean investors selling and hence a decline would seem justified.

However, this is a debt fund. What exactly led to this decline in NAV when no market sentiment or selling was at play?

BR,

Ajay

The compnay must have messed up something 🙂

Are Liquid Funds good instruments to store emergency cash?

Hmm, you can use liquidfunds to park your emergency corpus.

Thanks Karthik 🙂

Right. But if I invest in a liquid fund, does it mean that the AMC Fund Manager can only pick debt instruments wherein the repay/maturity period is 91 days ?

For e.g., in the earlier chapters you mentioned that Large Cap funds means that the fund manager has to allocate >80% in large cap stocks (and the rest 20% is upto their judgment). Is there a similar mandate here (like >80% has to be in 91 days)?

I do realize that I don\’t need to be really concerned with the concept of maturity when investing in a liquid fund but it helps to know.

Yes, these are largely a mix of 91 day bills and TREPs, which are overnight debt.

Hi! Nice article on Liquid funds.

Are

\”182-day T-Bill, the maturity of 182 days

365 day T-bills, the maturity of 365 days\” not a part of liquid debt funds since they have maturity > 91 days? If no, which category do they belong to?

If you buy T bills, then yes, the maturity is 182 or 365 days, however, if you buy liquid debt funds then there is no concept of maturity as that is taken care by the fund itself.

Is it safe to invest retirement amount in debt funds. If yes, what should be the tenure. Please suggest. Thanks

Depends on your current age. If you are saving for retirement and you are sub 40, then you need to look at equity-oriented funds.

Hi Karthik,

Just wondered, isn\’t T-Bill arguably the SAFEST among all investments i.e even more than SBs and FDs? Ofcourse, the potential downside, not being fixed on long term basis thus having to roll them over again and again.

Would love to know your thoughts on this.

Of course it is, hence the low returns also with it 🙂

Respected sir ,

I have one question . can an individual apply for fund manager license or only corporate bodies can do that ?

It has to be a corporate body.

Hello Sir,

Firstly, I am totally new to the markets & financial field but this series has proved to be an excellent starting point – simple, crisp and easy to follow. Thank you!

My question – Why should I, as an individual opt to invest in a debt liquid fund v/s and FD to park spare cash – from what i gather, the returns and timelines are similar and a bank FD would carry a lower risk on my investment. Is there any specific advantage on choosing a debt liquid fund ?

Thats right, Vidya. At this point, FDs are safer and carries no additional risk. Its just that FD usually has a lockin but you can liquidate your investment in debt fund anytime you wish.

Please have a button at end of each chapter linking to this next.

Please look at the index on the left panel. We have just updated the entire reading experience on Varsity.

Hi Karthik, what are your views on Nippon India Liquid Fund Dir?

Now this fund has NAV around 4930 and I barely get units for 1000 rupees, so is this safe now to stay invested in this fund?

Appreciate your response on this.

I\’ve not checked that specific fund Rohan. But we have discussed the liquid fund, maybe you just put that lesson into practice 🙂

Do AMC have NAV for liquid bonds as well??

Liquid bonds?

Hi Karthik,

From investor prespective, it doesn\’t matter when the maturity period of 91 days are getting over for fund manager. Your 91 days period in liquid funds start from the date when you invest and after 91 days, it\’s get over. Am I correct?

What about if I don\’t reedeem the money after 91 days, will it roll over for another 91 days (and I could face the same liquidity problems in case I try to sell in between). Please advise.

Thats correct. You as an investor only need to be aware that these funds have 91-day maturity bills in the portfolio and therefore the risk associated with it. You need not have to rollover, you just hold the fund and the fund manager does what he is supposed to do. You can hold it for however long you want.

Hi,

in example given above for property, if we take a loan from bank then we give collateral ie our property. If company making any bonds with AMC, then what is collateral that company gives to AMC.

If the company winds up then the investors money gone forever.

Yeah, hence its best not to complicate these things.

Yes sir, the example was just hypothetical.

But sir we were discussing about a risk-free bonds.

Assuming AAA-rated bonds to be risk free as well even then the problem remains the same.

Why to buy a portfolio of mixed bonds assuming they are risk free when you can buy highest return bond from that portfolio?

AAA Bonds are not risk-free. Only the Sovereign bonds are perceived as credit risk-free…that too internally within the country. For example, S&P can downgrade India bonds..but internally we all know that RBI may not let us down (hopefully). You always need a portfolio to diversify risks of all kinds…known and unknown.

I am sorry sir. I still didnt understand.

Yes we have to look at returns.

Say there are 5 gov bonds in a portfolio.

Bond A- 5%

Bond B- 6%

Bond C- 7%

Bond D- 8%

Bond E- 9%

Now if we diversify between these say equally, then the return will be 7%.

But if we buy bond E directly then we can get 9% right?

Yeah, but that is if you find a bond which gives you 9% and is also credit risk-free. But hypothetically if this were true, there will always exist a AAA-rated corporate bond with 9.5%, wouldn\’t you want that?

Thanks Karthik for the article. It is nice reading about the concepts. The article about how to select mutual funds will help most of the readers that too when the market is showing lot of opportunities during this COVID pandemic. Many people say to consider multiple factors while selecting mutual fund like past performance and Greeks like alpha standards deviation which is like a bouncer for most of us. Please consider this kind request of writing the article about selection criteria on behalf of majority of the readers at the earliest.

Am always fan of your article. Storytelling is a good way to convey message in any article and you definitely have it. I have been in and out of equity market since 2008 but without knowing a bit. I was introduced to varsity knowledge base by my cousin in 2018 and ever since I view the market very differently. Kudos to you and your team.

Thanks for the kind words, Prasad. Yes, I will shart writing about it shortly.

Hey sir.

I am sorry but i didnt understand the concept behind these funds.

Why to diversify between different Government bonds if they are risk-free? Why not to invest in the bond with the highest return directly?

Thank you.

While risk is one part, you also need to look at returns right 🙂

You diversify if to improve the overall return profile of the fund and fare better than the rest in the AMC industry.

Hi Sir,

Do you have article about how to select mutual funds and build a portfolio? If you have kindly share

Not yet, plan to write that shortly.

got it, thanks, stay safe

You too!

I don\’t understand how a fall in credit rating might affect the return of the CP, for that to happen, the company has to actually default on its payment and the credit rating can fall due to other reasons too.

It would be better if the mechanism of the credit rating is clarified to me first, I might have misunderstood it

Thank you

Credit rating in an indication of the probability of default. As and when the probability increases (with credit downgrade), the price cracks. Remember, markets will not wait for the final outcome, it will react much earlier to it.

When i choose to invest in a debt fund which has investments made into CP / T-bills of short maturity period (say 91 days) what happens to the mutual fund after that? I am assuming the fund manager will swap those funds for another fund and continue to maintain the Mutual Fund active. Its like replacing 1 spare part of a machine with a new one.. Is my understanding right?

They continuously invest in securities which have short maturities. Yes, that\’s right they churn it regularly.

Hey,

I just wanted to know that when can we expect Financial Modelling and Financial Valuation certification course from Zerodha (approx timeframe). I am eagerly awaiting for the same and the 2nd question is

Are there any certification courses on Mutual Funds that Zerodha is offering and if not are there any plans to launch the same?

Financial modelling I will start maybe by mid-July 🙂

No certificate courses on MF yet, will probably include one in the app sometime soon.

Sir, I have gone through all the modules in varsity but I don\’t have practical experience in trading. I became your big fan after reading this invaluable content. Could you please suggest few books on investing?

Happy to note that, Prithvi. At the end of Fundamental Analysis module, I have suggested a few books. Please do give it try.

Hi sir,

I deeply appreciate the great initiative you have taken to educate us. Hats off to your immense knowledge in this field. Thanks a lot for this great content. Could you please suggest further reading to learn more about intraday trading and investing?

Thanks for the kind words, Prithvi. I\’m glad you liked the content here.

While there are plenty of books on investing, I hardly find any on intraday setups. Let me look for it again.

Hey,

1. What are Zero coupon / Deep discount Bonds? If they don\’t yield interest (assumption), why would anybody invest in them?

2. Are bonds unsecured like CP\’s ?

3. In the HDFC Liquid Fund example above why is there no coupon% for Treasury Bills?

1) Ppl invest for the discount so that they can redeem for face value

2) Bonds can be secured or unsecured

3) T Bills are zero-coupon bills, bought at a discount.

As the interest income from bank fixed deposit is fully taxable ,will there be any deductions on the interest income which we had earned through liquid funds?as it was the short term gain?

Yes, they are treated the same way.

Will there be any tax deductions on the interest income which we had earned through liquid funds?

No, not really.

Can you please tell which has low risk commercial papers or certificate of deposit?

Hmm, PSU CDs maybe 🙂

Thanks,

I have read this module fully and others 4 or 5 modules… Plz solve my one dilema … I have not invested anywhere till now.. now I want to invest for long time.. I am a government employee… With decent earning..But the dilemma is this when high qualified fund manager after using all the knowledge just give 6 to 7 percent return than why we should Not invest money in small saving scheme like PF , SUKANYA CHILD scheme etc… Why go for mutual fund….??

Vipin these are debt funds. Equities have a higher potential. PPF is a great option as well. I will discuss MF portfolio construction soon.

Hi ,.

Sir

I am in this lockdown period while doing my government duty .. is too much concerned about my father investment in sbi credit risk regular plan growth. As the investment is around 25 laks it\’s been 2 year and 8 months…. Of that investment.. Plz tell is it safe there…. Or I should redeem..plz

Vipin, I\’m not a financial advisor, so I cannot advise. Having said that, I don\’t like credit risk funds as it carries a high degree of risk. I\’d avoid using credit risk fund. Please do check with your financial advisor for this.

Sir, I have invested in Aditya Birla Sun Life Floating Rate Fund – Direct Plan – Growth.

The returns are so far, so good.

Kindly share some light on floater debt funds please.

I will try and do that in the coming few chapters.

Are there liquid funds , which invest in only T -Bills so credit risk can be avoided

I think only Quantum Liquid funds do that.

I understand that there is some credit and default risk with certificate of deposit, though they may be considered low risk. My question specifically pertains to liquidity risk. Are these assets liquid or do they need to be held to maturity. I assume CDs are not traded and so, can they be redeemed to meet liquidity obligations if required prior to maturity.

Liquidity is generally on the lower side, its best to held to maturity, interim redemptions may not be feasible.

How safe is Franklin liquid fund in todays situation ( ongoing debt fund saga and the pandemic). A glance at their portfolio shows that they are not having any Gov-securities in stark contrast to the rest of the liquid funds available for pledging in zerodha.

Hate to say, but you should avoid investments here.

How safe are Certificate of Deposit held in the portfolio of Liquid Mutual funds. I assume they are safer than commercial paper. Are they relatively low credit rsk?

They are relatively low risk. But the end of the day, they are all issued by Pvt entities, carries both rating and default risk.

Karthik, most of the liquid funds have something called Certificate of Deposits, which I presume is basically FDs. Can you tell what is their risk factor compared to Commercial paper & T Bills?

1) \’Commercial Papers’ or CPs, issued by companies. CPs are unsecured

2)‘Certificate of Deposits’ or CDs. CDs are issued by banks to entities depositing money

3)T-Bills, issued by the Government, carries sovereign guarantee

can you suggest other liquid funds .to park for shorter time and pledge to get margins

I think they are all the same, more or less. Do check the asset ratings once.

Hi sir,

Any platform you would suggest to start mutual fund investment? There are many apps which have come up. Are they safe?

Yes, please do check out Zerodha\’s own MF platform. Its called Coin – https://coin.zerodha.com/

hi karthik,

returns are better in liquid funds in comparison to liquid bees post tax.

ur views

Hmm, perhaps. However, you should not be chasing returns with liquid investments 🙂

HI KARTHIK.

PLZ TELL ME THE MAIN DIFFERENCES BETWEEN LIQUID BEES (NIPPON) AND LIQUID FUND (AXIS ,HDFC,ABSL ETC).

WHICH INSTRUMENTS IS SAFE IF I M HOLDING IT FOR MORE THAN 5 YEARS FOR FNO TRADING

ANNUALY RETURNS

RISK

DEFAULT

POST TAX RETURNS

ANY POINT U WANT TO ADD ACCORDING TO YOUR EXPERIENCE .

Bees are exchange-traded funds whereas a fund has a mutual fund structure. Although ETFs are better, they lack liquidity in India. Hence Liquid funds are a better option.

hi karthik ,

when is the best time to redeem our mutual funds (liquid funds) after 2 pm or before 2 pm to get maximum return .

any experience u can share on this .

That time does really matter, Ankit 🙂

hi karthik.

can u provide the link of rbi website (ncd issue

)

Auction details will be mentioned here – https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_PressReleaseDisplay.aspx

hi karthik,

on 22 march nav 2186.55

23 march nav 2184.78

24 march nav 2183.60

and after that it recovered

plz check

axis liquid fund regular

That would be a minor dip, like any other fund. This is possible given the fact that the entire market (across asset classes) were volatile.

HI karthik,

i see the chart of axis liquid fund.

there is a drop in nav between 15 march 2020 to 30 march 2020.and then it recovered

what is the reason behind the drop of nav .

plz explain .

Ankit, I don\’t see any dip in the fund.

HI KARTHIK .

HOW CAN I KEEP A TRACK ON UPCOMING NCD ISSUES

You can check the RBI announcements (press release) section of the site.

hello karhthik,

Can you please share the link of hedging of portfolio via option. Actually i am not able to find where exactly mentioned in option theory?

We dont have content on that. However, we do have a chapter on hedging via futures, check this – https://zerodha.com/varsity/chapter/hedging-futures/

Thanks for the explanation. You mean once the interest is received it would almost always increase right and decrease if the company defaults in repayment?

Yeah, all of these things adds to the NAV fluctuation.

Hi Karthik,

Could you shed some light on how the NAV of the liquid fund fluctuates. I know in case of equity MF\’s it\’s based on the actual share price of the companies but in case of liquid funds the fund lends the money to corporates or government and gets the interest as return. So not sure how the NAV changes here.

It does not change as much as an EQ fund does. The NAV is impacted by the payments received in terms of coupons which results in a change in the fund size and therefore the NAV.

\”The bulk of HDFC’s portfolio, i.e. 89.95%, is parked in Government securities\” – Just curious how you have calculated this percentage. As I could find from the Feb2020 Portfolio Summary taken from hdfcfund website, this value is only 38.35% and CPs are 42.28% of the portfolio as against 9.12% that you have mentioned. Can you please help me here?

DEBT INSTRUMENTS -> 9.12% (Non-Convertible debentures / Bonds – 6.34% and Zero Coupon Bonds / Deep Discount Bonds – 2.78%)

MONEY MARKET INSTRUMENTS -> 89.95% (Certificate Of Deposit (CD) – 9.32%, Commercial Papers (CP) – 42.28%, Gov Sec – 38.35%)

Hey, thanks so much pointing this out. I think I made an inadvertent mistake. I looked at the wrong subtotal. Will change this right away.

Hey Karthik ,

You guys at Zerodha are doing great job by helping many budding investors like us. Thank you for bringing financial literacy among young investors of India. These modules on Varsity made me clear on every aspect of investing and trading.

Happy to note that, thanks for letting us know 🙂

I am not getting how NAV is falling upon downgrading of Credit rating? The interest payment on the bond is fixed.

Credit rating is an indicator of a likely default on repayment. If the rating falls, then the probability of default increases, hence the bonds are sold in the market, bringing the value down. Therefore the drop in NAV.

update app asap please

We are working on the app sir.

Thanks… eagerly waiting for this…

And.. why is all the Varsity web content not present on Varsity app yet ?

We are working with one module at a time, hence the delay.

when is the next chapters coming ?

This week, Jatin.

SO. are Liquid Funds Close Ended funds ? ,As Company or government Repays the the due and Fund Closes and Company stating with New Portfolio.

and If Not the is Liquid Fund Portfolio Changes every time by 91 Day\’s?

These are open-ended funds. The fund manager keeps rolling into new CPs and bills.

Why are these modules not uploaded or updated in the Zerodha varsity app? It\’ll be very convenient to read from there.

This module is still work in progress. However, we are working on it, hopefully soon.

Hey Karthik,

Is there any chance you manage any fund? If so, I would like to invest in that fund.

No Sir, we don\’t manage any funds 🙂

Sir if the credit rating agencies downgrades the cps and if we want to exit from that fund can\’t we exit before the maturity.

You certainly can, Srinath.

Sir,

If I transfer it to Zerodha and then want to hedge, can you please provide me any document on how to do this hedging against those MF in Kite?

One of the best ways to do this would be with options. You can read more about options here – https://zerodha.com/varsity/module/option-theory/

Hi,

Where is the link that continues to explain about other types of debt funds? I wanted to read more about the other types of debt funds. I am not able to find any more chapters that discusses other types of debt fund.

Thanks

This is work in progress, I\’ll put up the next article in few days.

Same question

Sir,

I have around Rs. 10 lakhs value of Mutual Fund with some other broker. If I transfer the whole amount to Zerodha, then is there any possibility to hedge Mutual fund in Zerodha using OTM Options in Kite against this? I want to generate some return when my MF value goes downside. Is it possible? If possible can you guide me?

Sir, if these units are in DEMAT mode, then yes, you can transfer it quite easily. If it is in non DEMAT mode, then you will have to sell the units, realise gains and then re invest the same. Also, to be fair, if these units are with another broker, then I\’m sure the broker allows you to trade F&O, so you can hedge it there itself.

Sir if we have to invest in a liquid fund can invest through zerodha directly,like we invest in equities directly,and where to check for the amount of exposure of cp and government securities for a particular liquid fund.

Yes, you can invest in liquid funds via Coin. Check this – https://coin.zerodha.com/. However, for the portfolio constituents, you will have to check the AMC\’s website. Look for it under the statutory disclosure.