17.1 – Background

In the earlier chapter we had this discussion about the range within which Nifty is likely to trade given that we know its annualized volatility. We arrived at an upper and lower end range for Nifty and even concluded that Nifty is likely to trade within the calculated range.

Fair enough, but how sure are we about this? Is there a possibility that Nifty would trade outside this range? If yes, what is the probability that it will trade outside the range and what is the probability that Nifty will trade within the range? If there is an outside range, then what are its values?

Finding answers to these questions are very important for several reasons. If not for anything it will lay down a very basic foundation to a quantitative approach to markets, which is very different from the regular fundamental and technical analysis thought process.

So let us dig a bit deeper and get our answers.

17.2 – Random Walk

The discussion we are about to have is extremely important and highly relevant to the topic at hand, and of course very interesting as well.

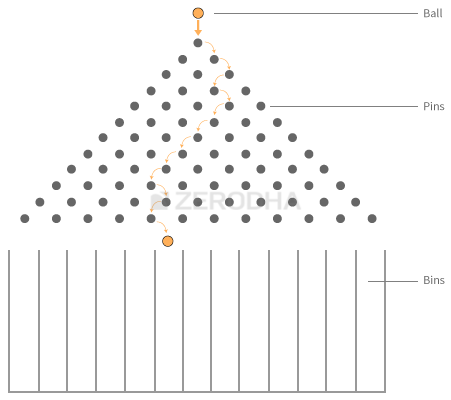

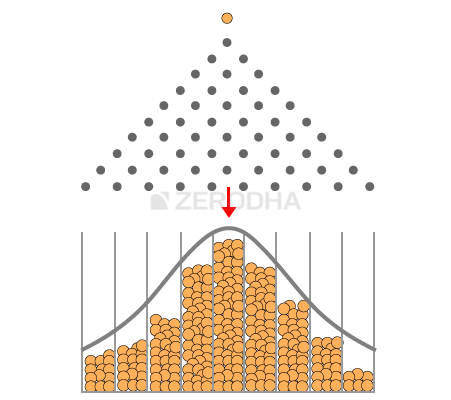

Have a look at the image below –

What you see is called a ‘Galton Board’. A Galton Board has pins stuck to a board. Collecting bins are placed right below these pins.

The idea is to drop a small ball from above the pins. Moment you drop the ball, it encounters the first pin after which the ball can either turn left or turn right before it encounters another pin. The same procedure repeats until the ball trickles down and falls into one of the bins below.

Do note, once you drop the ball from top, you cannot do anything to artificially control the path that the ball takes before it finally rests in one of the bins. The path that the ball takes is completely natural and is not predefined or controlled. For this particular reason, the path that the ball takes is called the ‘Random Walk’.

Now, can you imagine what would happen if you were to drop several such balls one after the other? Obviously each ball will take a random walk before it falls into one of the bins. However what do you think about the distribution of these balls in the bins?.

- Will they all fall in the same bin? or

- Will they all get distributed equally across the bins? or

- Will they randomly fall across the various bins?

I’m sure people not familiar with this experiment would be tempted to think that the balls would fall randomly across various bins and does not really follow any particular pattern. But this does not happen, there seems to be an order here.

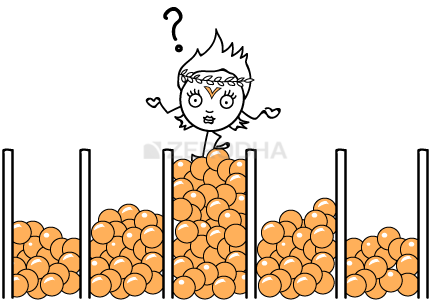

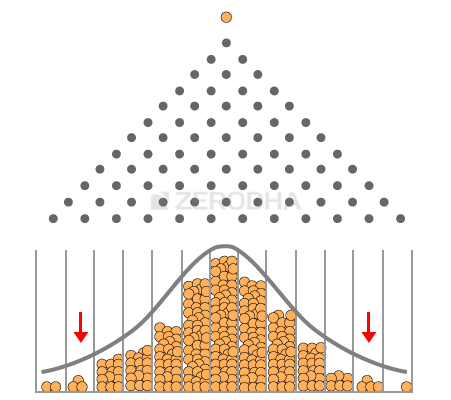

Have a look at the image below –

It appears that when you drop several balls on the Galton Board, with each ball taking a random walk, they all get distributed in a particular way –

- Most of the balls tend to fall in the central bin

- As you move further away from the central bin (either to the left or right), there are fewer balls

- The bins at extreme ends have very few balls

A distribution of this sort is called the “Normal Distribution”. You may have heard of the bell curve from your school days, bell curve is nothing but the normal distribution. Now here is the best part, irrespective of how many times you repeat this experiment, the balls always get distributed to form a normal distribution.

This is a very popular experiment called the Galton Board experiment; I would strongly recommend you to watch this beautiful video to understand this discussion better –

So why do you think we are discussing the Galton Board experiment and the Normal Distribution?

Well many things in real life follow this natural order. For example –

- Gather a bunch of adults and measure their weights – segregate the weights across bins (call them the weight bins) like 40kgs to 50kgs, 50kgs to 60kgs, 60kgs to 70kgs etc. Count the number of people across each bin and you end up getting a normal distribution

- Conduct the same experiment with people’s height and you will end up getting a normal distribution

- You will get a Normal Distribution with people’s shoe size

- Weight of fruits, vegetables

- Commute time on a given route

- Lifetime of batteries

This list can go on and on, however I would like to draw your attention to one more interesting variable that follows the normal distribution – the daily returns of a stock!

The daily returns of a stock or an index cannot be predicted – meaning if you were to ask me what will be return on TCS tomorrow I will not be able to tell you, this is more like the random walk that the ball takes. However if I collect the daily returns of the stock for a certain period and see the distribution of these returns – I get to see a normal distribution aka the bell curve!

To drive this point across I have plotted the distribution of the daily returns of the following stocks/indices –

- Nifty (index)

- Bank Nifty ( index)

- TCS (large cap)

- Cipla (large cap)

- Kitex Garments (small cap)

- Astral Poly (small cap)

As you can see the daily returns of the stocks and indices clearly follow a normal distribution.

Fair enough, but I guess by now you would be curious to know why is this important and how is it connected to Volatility? Bear with me for a little longer and you will know why I’m talking about this.

17.3 – Normal Distribution

I think the following discussion could be a bit overwhelming for a person exploring the concept of normal distribution for the first time. So here is what I will do – I will explain the concept of normal distribution, relate this concept to the Galton board experiment, and then extrapolate it to the stock markets. I hope this will help you grasp the gist better.

So besides the Normal Distribution there are other distributions across which data can be distributed. Different data sets are distributed in different statistical ways. Some of the other data distribution patterns are – binomial distribution, uniform distribution, poisson distribution, chi square distribution etc. However the normal distribution pattern is probably the most well understood and researched distribution amongst the other distributions.

The normal distribution has a set of characteristics that helps us develop insights into the data set. The normal distribution curve can be fully described by two numbers – the distribution’s mean (average) and standard deviation.

The mean is the central value where maximum values are concentrated. This is the average value of the distribution. For instance, in the Galton board experiment the mean is that bin which has the maximum numbers of balls in it.

So if I were to number the bins (starting from the left) as 1, 2, 3…all the way upto 9 (right most), then the 5th bin (marked by a red arrow) is the ‘average’ bin. Keeping the average bin as a reference, the data is spread out on either sides of this average reference value. The way the data is spread out (dispersion as it is called) is quantified by the standard deviation (recollect this also happens to be the volatility in the stock market context).

Here is something you need to know – when someone says ‘Standard Deviation (SD)’ by default they are referring to the 1st SD. Likewise there is 2nd standard deviation (2SD), 3rd standard deviation (SD) etc. So when I say SD, I’m referring to just the standard deviation value, 2SD would refer to 2 times the SD value, 3 SD would refer to 3 times the SD value so on and so forth.

For example assume in case of the Galton Board experiment the SD is 1 and average is 5. Then,

- 1 SD would encompass bins between 4th bin (5 – 1 ) and 6th bin (5 + 1). This is 1 bin to the left and 1 bin to the right of the average bin

- 2 SD would encompass bins between 3rd bin (5 – 2*1) and 7th bin (5 + 2*1)

- 3 SD would encompass bins between 2nd bin (5 – 3*1) and 8th bin (5 + 3*1)

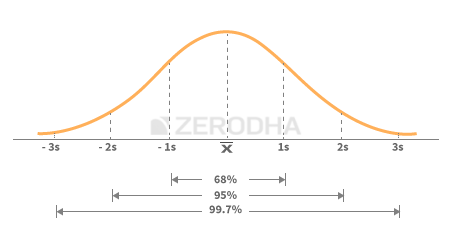

Now keeping the above in perspective, here is the general theory around the normal distribution which you should know –

- Within the 1st standard deviation one can observe 68% of the data

- Within the 2nd standard deviation one can observe 95% of the data

- Within the 3rd standard deviation one can observe 99.7% of the data

The following image should help you visualize the above –

Applying this to the Galton board experiment –

- Within the 1st standard deviation i.e between 4th and 6th bin we can observe that 68% of balls are collected

- Within the 2nd standard deviation i.e between 3rd and 7th bin we can observe that 95% of balls are collected

- Within the 3rd standard deviation i.e between 2nd and 8th bin we can observe that 99.7% of balls are collected

Keeping the above in perspective, let us assume you are about to drop a ball on the Galton board and before doing so we both engage in a conversation –

You – I’m about to drop a ball, can you guess which bin the ball will fall into?

Me – No, I cannot as each ball takes a random walk. However, I can predict the range of bins in which it may fall

You – Can you predict the range?

Me – Most probably the ball will fall between the 4th and the 6th bin

You – Well, how sure are you about this?

Me – I’m 68% confident that it would fall anywhere between the 4th and the 6th bin

You – Well, 68% is a bit low on accuracy, can you estimate the range with a greater accuracy?

Me – Sure, I can. The ball is likely to fall between the 3rd and 7th bin, and I’m 95% sure about this. If you want an even higher accuracy then I’d say that the ball is likely to fall between the 2nd and 8th bin and I’m 99.5% sure about this

You – Nice, does that mean there is no chance for the ball to fall in either the 1st or 10th bin?

Me – Well, there is certainly a chance for the ball to fall in one of the bins outside the 3rd SD bins but the chance is very low

You – How low?

Me – The chance is as low as spotting a ‘Black Swan’ in a river. Probability wise, the chance is less than 0.5%

You – Tell me more about the Black Swan

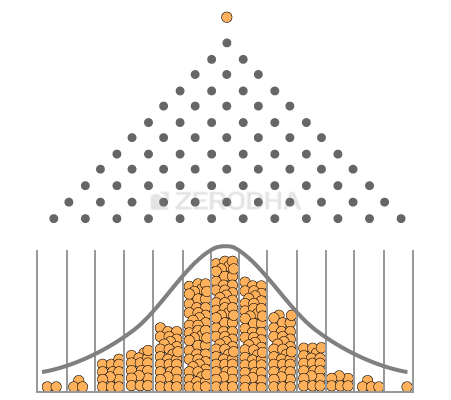

Me – Black Swan ‘events’ as they are called, are events (like the ball falling in 1st or 10th bin) that have a low probability of occurrence. But one should be aware that black swan events have a non-zero probability and it can certainly occur – when and how is hard to predict. In the picture below you can see the occurrence of a black swan event –

In the above picture there are so many balls that are dropped, but only a handful of them collect at the extreme ends.

17.4 – Normal Distribution and stock returns

Hopefully the above discussion should have given you a quick introduction to the normal distribution. The reason why we are talking about normal distribution is that the daily returns of the stock/indices also form a bell curve or a normal distribution. This implies that if we know the mean and standard deviation of the stock return, then we can develop a greater insight into the behavior of the stock’s returns or its dispersion. For sake of this discussion, let us take up the case of Nifty and do some analysis.

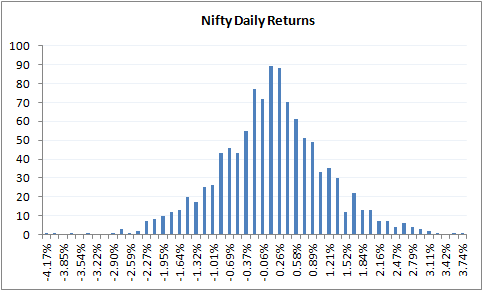

To begin with, here is the distribution of Nifty’s daily returns is –

As we can see the daily returns are clearly distributed normally. I’ve calculated the average and standard deviation for this distribution (in case you are wondering how to calculate the same, please do refer to the previous chapter). Remember to calculate these values we need to calculate the log daily returns.

- Daily Average / Mean = 0.04%

- Daily Standard Deviation / Volatility = 1.046%

- Current market price of Nifty = 8337

Do note, an average of 0.04% indicates that the daily returns of nifty are centered at 0.04%. Now keeping this information in perspective let us calculate the following things –

- The range within which Nifty is likely to trade in the next 1 year

- The range within which Nifty is likely to trade over the next 30 days.

For both the above calculations, we will use 1 and 2 standard deviation meaning with 68% and 95% confidence.

Solution 1 – (Nifty’s range for next 1 year)

Average = 0.04%

SD = 1.046%

Let us convert this to annualized numbers –

Average = 0.04*252 = 9.66%

SD = 1.046% * Sqrt (252) = 16.61%

So with 68% confidence I can say that the value of Nifty is likely to be in the range of –

= Average + 1 SD (Upper Range) and Average – 1 SD (Lower Range)

= 9.66% + 16.61% = 26.66%

= 9.66% – 16.61% = -6.95%

Note these % are log percentages (as we have calculated this on log daily returns), so we need to convert these back to regular %, we can do that directly and get the range value (w.r.t to Nifty’s CMP of 8337) –

Upper Range

= 8337 *exponential (26.66%)

= 10841

And for lower range –

= 8337 * exponential (-6.95%)

= 7777

The above calculation suggests that Nifty is likely to trade somewhere between 7777 and 10841. How confident I am about this? – Well as you know I’m 68% confident about this.

Let us increase the confidence level to 95% or the 2nd standard deviation and check what values we get –

Average + 2 SD (Upper Range) and Average – 2 SD (Lower Range)

= 9.66% + 2* 16.61% = 42.87%

= 9.66% – 2* 16.61% = -23.56%

Hence the range works out to –

Upper Range

= 8337 *exponential (42.87%)

= 12800

And for lower range –

= 8337 * exponential (-23.56%)

= 6587

The above calculation suggests that with 95% confidence Nifty is likely to trade anywhere in the range of 6587 and 12800 over the next one year. Also as you can notice when we want higher accuracy, the range becomes much larger.

I would suggest you do the same exercise for 99.7% confidence or with 3SD and figure out what kind of range numbers you get.

Now, assume you do the range calculation of Nifty at 3SD level and get the lower range value of Nifty as 5000 (I’m just quoting this as a place holder number here), does this mean Nifty cannot go below 5000? Well it certainly can but the chance of going below 5000 is low, and if it really does go below 5000 then it can be termed as a black swan event. You can extend the same argument to the upper end range as well.

Solution 2 – (Nifty’s range for next 30 days)

We know the daily mean and SD –

Average = 0.04%

SD = 1.046%

Since we are interested in calculating the range for next 30 days, we need to convert the same for the desired time period –

Average = 0.04% * 30 = 1.15%

SD = 1.046% * sqrt (30) = 5.73%

So with 68% confidence I can say that, the value of Nifty over the next 30 days is likely to be in the range of –

= Average + 1 SD (Upper Range) and Average – 1 SD (Lower Range)

= 1.15% + 5.73% = 6.88%

= 1.15% – 5.73% = – 4.58%

Note these % are log percentages, so we need to convert them back to regular %, we can do that directly and get the range value (w.r.t to Nifty’s CMP of 8337) –

= 8337 *exponential (6.88%)

= 8930

And for lower range –

= 8337 * exponential (-4.58%)

= 7963

The above calculation suggests that with 68% confidence level I can estimate Nifty to trade somewhere between 8930 and 7963 over the next 30 days.

Let us increase the confidence level to 95% or the 2nd standard deviation and check what values we get –

Average + 2 SD (Upper Range) and Average – 2 SD (Lower Range)

= 1.15% + 2* 5.73% = 12.61%

= 1.15% – 2* 5.73% = -10.31%

Hence the range works out to –

= 8337 *exponential (12.61%)

= 9457 (Upper Range)

And for lower range –

= 8337 * exponential (-10.31%)

= 7520

I hope the above calculations are clear to you. You can also download the MS excel that I’ve used to make these calculations.

Of course you may have a very valid point at this stage – normal distribution is fine, but how do I get to use the information to trade? I guess as such this chapter is quite long enough to accommodate more concepts. Hence we will move the application part to the next chapter. In the next chapter we will explore the applications of standard deviation (volatility) and its relevance to trading. We will discuss two important topics in the next chapter (1) How to select strikes that can be sold/written using normal distribution and (2) How to set up stoploss using volatility.

Of course, do remember eventually the idea is to discuss Vega and its effect on options premium.

Key takeaways from this chapter

- The daily returns of the stock is a random walk, highly difficult to predict

- The returns of the stock is normally distributed or rather close to normal distribution

- In a normal distribution the data is centered around the mean and the dispersion is measured by the standard deviation

- Within 1 SD we can observe 68% of the data

- Within 2 SD we can observe 95% of the data

- Within 3 SD we can observe 99.5% of the data

- Events occurring outside the 3rd standard deviation are referred to as Black Swan events

- Using the SD values we can calculate the upper and lower value of stocks/indices

Karthik sir, off late I\’ve been reading books by Nassim Nicholas Taleb and he says that models like black scholes, normal distribution, VaR are useless because they ignore real world risks and fat tails as he calls them. What do you think about it? Should I as a retail trader worry about reliability of these models? Taleb is really interesting guy but also complex to read sometimes. Your guidence please.

I cant really dispute what Taleb says, but that said, treat this as a reference point to give you a sense of what should be the price. That approach should be good to go with I guess.

Karthik sir,

In the normal distribution that you plotted for Nifty 50 & other stocks, what is the parameter on the Y-axis ? From where the Y-axis value has been taken, pls clarify.

Its the number of observations Vaishak. As in how many times a certain return has occurred in the timeline you are studying. For example – A return of 5% has occurred 15 times over the last 1 year.

As it is daily returns so assume it as number of days

Sorry, dint get the query. Can you please elaborate? Thanks.

Hi Sir,

why Bin width divided by 50 ? and is it the same for stocks and other Index? Please guide.

and one more question sir,

Do we need to take five years data as base to calculate? as I can see you took data for 5 years (2011 to 2015).

5 years is good, but if you have a shorter term approach, then even last 2 years is fine.

Yes, its independent of the underlying asset. The idea is to look at the size of the data set and then take a call on how many bins etc.

Hello Karthik Sir, I am back after a long time as I can\’t forget the impact of these chapters. I am not able to download your sample Excel for the Normal Distribution calculation. Could you please help here? I think some issue.

Hi Suvajit, welcome back 🙂

It seems to be working fine for me. Try changing the browser?

Hi Karthik,

I want to calculate the Nifty range for July 25. Which period of historical Nifty data should be used for this calculation? (1-04-24) to (31-04-25) or (01-06-24) to (01-06-25) or (01-06-25 to 30-06-25)

Thank You 🙂

I\’d suggest you use the latest 1 year data for this, Soham.

Hi Sir, Excellent way of teaching. Some people are born natural teachers. I had one query, why have you divided by 50 in Binary width calculation in excel?

Thanks for the kind words, Rahul. 50 is an arbitrary number arrived at based on the number of data points.

Is it fair to say that arbitrary number should be such that the normal distribution graph looks symmetrical from both sides? Nifty example, you have taken 50 but when I take the same for Kotak Bank, the graph is a bit asymmetrical. Hence I have used 43 such that maximum values lie in the middle of the X-axis.

One thing you can do is think of it in this way – for every n number of data points, have y bins,

sir in the annual volatility formula if we take days 365 in all the cases then it is more reliable than the taking no. of observation we took in the SD formula. eg. =1.04%*SQRT(365). I m suggesting you to calculate annual volatility by taking always 365 days and then compare it with nse website data. i have check it many times and it is always same as nse data rather than taking no. of observations.

And because of this im not getting calculation part further .

Do check it and if find same observation as me then change the calculation data.

There is a fundamental difference between this method and NSE\’s computation of volatility. NSE does this mainly in terms of figuring the margin required for position, where in they give more weightage to recent data points. Where as, in this method discussed, we give equal weights to all data points as the objective is to simlply figure the overall volatility of the instruments. Hence there will be some difference in the final volatility values of this method vs NSE\’s.

\”You – Tell me more about the Black Swan

Me – Black Swan ‘events’ as they are called, are events (like the ball falling in 1st or 10th bin) that have a low probability of occurrence. But one should be aware that black swan events have a non-zero probability and it can certainly occur – when and how is hard to predict. In the picture below you can see the occurrence of a black swan event –

In the above picture there are so many balls that are dropped, but only a handful of them collect at the extreme ends.\”

I would like to add that \”While it’s true that Black Swan events are rare (‘only a handful collect at the extreme ends’), the real issue isn’t their frequency—it’s their catastrophic impact, as they can wipe out years of steady profits overnight and even push businesses or investors into bankruptcy. History has repeatedly shown this: the 1929 Great Depression saw the Dow Jones plunge 89%, leading to mass unemployment; the 1973 Oil Crisis triggered a global recession with markets falling 48%; Black Monday (1987) wiped out 22% of the U.S. stock market in a single day; the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis led to currency collapses and stock declines of over 60% in some economies; the 2000 Dot-com Bubble erased 78% of the Nasdaq’s value; the 2008 Global Financial Crisis led to a 54% decline in the S&P 500, causing widespread bankruptcies; and the 2020 COVID-19 Crash saw global markets plummet 30% in weeks, disrupting entire industries. These crises prove that it’s not enough to acknowledge that Black Swans can happen—their disproportionate impact makes risk management and preparedness far more important than probability estimates.\”

What do you think?

Yes sir. Thats right.

Hi Karthik, yes, I understood the plots now. Thanks a lot.

Happy learning, Pradeep!

Sorry for my mistake here. I wrote \”The question is what does the Y axis represent? It seems to be some normalised scale of the pricing of the index or equity closing value\”. It should read \’normalised on some scale of the daily return (or whatever period of interest we are using– such as annual or quarterly return etc). The rest of the query remains the same: how is \’the return percentage\’ normalised? That is, what does 100 represent?

Apologies for this inconvenience.

Please do check my previous response, let me know if it makes sense.

Please excuse me for asking this so late. Also, since all earlier comments are very appreciative of this article, it is very likely its me who is getting it all wrong. But please allow me to ask this rather fundamental question.

Firstly, I\’d like to clarify I am not into F&O, but was directed here, by your Chapter 22 on MF parameters, to understand SD calculations and how could they be applied to MF risk evaluation.

https://zerodha.com/varsity/chapter/mutual-fund-risk-metrics/

So, in all above plots on normal distribution, it is my understanding that the X axis is the Standard Distribution in percent. The question is what does the Y axis represent? It seems to be some normalised scale of the pricing of the index or equity closing value. But then what is the process of this norrmalisation? In other words, what does 100 represent? By the same token, you also represent the Average of the entity (Index or equity price) over the period of interest as a certain percentage. So, I wonder percentage of what— (put differently, what is \’100\’ on this scale)?

Thanks in advance.

Hi Pradeep, so the Y axis represents the number of times a certain event has occurred. For example, in the Bank Nifty case, you can see a return of 0.07% has occurred 100 times, so has a return of 0.67%.

Sir you are really outstanding way to explain the every chapter till now what I read.Thank you so much for such great way explain everything.🙏🙏🙏🙏🙏🙏🙏🙇🙇🙇🙇

Thanks for the kind words, and happy learning, Bapi!

Very Informative Data

Happy learning 🙂

Can you please enable a dark mode for this website. Since I am reading from laptop, the large white background is straining my eyes and even in the lowest brightness settings it\’s still very bright.

Noted. You can also check the mobile app.

Sir. How to calculate daily mean / average?

I\’ve explained this in detail in this or the next chapter. But here are the steps –

1) Calculate the daily returs

2) Use excel function \’=Avg()\’, across all these returns to get the daily average return.

Thats it.

Sir in the example of nifty above you have calculated the daily returns right? (0.04%) and the daily volatility is represented as SD. So can you show how to you have calculated the Daily Returns Just for 1 or 2 days with the formula…..

I\’ve replied to your previous comment, please do check. Thanks.

Hi karthik Sir,

Here for nifty mean you have mentioned 0.04% but how did you arrive this value. Because the first value that we will derive from the last chapter was Daily volatility which is SD. So to calculate this mean is there a formula. Like for mean its always = outcomes/No of occurrences. How to get the daily average mean for indices and for any equity?

That is quite easy, in excel you first calculate the daily returns of the stock and then use the \’=Average()\’, function over the daily returns to get the mean.

sir can you explain why you multiply with exponential to the market price instaed of doing market price (1 +or- %)

sir in some examples you calculate range within directly without using daily mean .. then how to know the percentage of confidence weather 68% or 95% or 99%

when calculating the upper and lower ranges in the above examples every time you say \”Note these % are log percentages (as we have calculated this on log daily returns), so we need to convert these back to regular %, we can do that directly and get the range value\” my question here is that why calculate in logarithmic format why not we calculate simply in regular % in the first place \”or\” is that when we calculate for a larger period of time it automatically gets converted into logarithmic and we have convert it back into normal ?

If its for short data range, you can do that. No need to take log.

Excel sheet links are not working

Can you try downloading from another browser?

I am getting negative value for daily returns average. It\’s giving lower and higher end greater than current price. Is it normal?

If the stock is trending lower, then yes, why not 🙂

Thank you

zerodha team and specially karthik rangappa for taking pain

of reading our query and replying

thanks a lot

Happy learning, Javed!

MS excel download is not working

where is excel file

Try downloading from a different browser.

Hi did the equation

my answer differs

==============================

as in the chapter…………………….10841

Upper Range

8337 *exponential (26.66%)

10841

=====================================

i tried to solve mine is coming to ……….10560

26.66% of 8337

is 2222.6

8337+2223=10560

how is yours coming 10841 ???

YOu need to ensure you are using the exponential function on excel.

pls explain this equation

Upper Range

= 8337 *exponential (26.66%)

= 10841

please explain this

= 8337 *exponential (12.61%)

= 9457 (Upper Range)

Its a calculation. Have explained in the chapter itself.

sir

how do we calculate this

= 8337 *exponential (6.88%)

= 8930

You can apply this function on excel and get the answer.

I have a doubt like how to calculate the daily average of nifty 50

i couldnot understand thatr one

Daily average of what? Returns or price change? If its returns you calculate the daily returns, and apply the average function over the time series.

Very informative!! what is data range used to calculated SD, is it past 1 year data or 2 year or what?

You can stick to 1 year.

Sir, I am not able to download the excel sheet can you please fix the problem

Can you try downloading from another browser? Usually that works.

Hi karthik,

Not able to download excel..please send link

Can you try from another browser?

Hello Karthick sir,

1. as per your guidance & steps calculated SD for Nifty 50 & Finnifty but the Mean Average turnedd out to be in Negative marks ex(-0.05), in that case how shall we calculate the prediction range month ahead from today ?

2. (like -*- = + will it applicable in calculaton or were i wring in XL calculation…..

3. What shall we do now in prediction????????

The mean is usually a very small number, close to zero. So this is not surprising. That said, I\’d still suggest you double check all the numbers and calculation steps once again.

Hi Karthik, I am constantly learning from your beautifully crafted material, it is practical and really helpful. Thanks for that!

Question: Nifty’s range for next 30 days (7963 – 8930) calculated. Lets say Nifty drop or jump significantly in next session and new data come into the data series for next day and range keep changing constantly for defined period of next 30 days. Shall we focus on the range calculated on first day for next 30 days Or need to keep an eye simultaneously on changing range on the basis of new data come into the data series? Only first range is sufficient or keep an eye on both?

Thanks Navneet. If there is new data and there is significant change, then you should consider and reevaluate using the new data 🙂

Interesting insights about normal distribution and finding the relation with real time examples. Thanks for enriching our learning.

Glad you liked it Raman, happy learning 🙂

Dear Sir/Madam,

As stock prices cannot take negative values, instead of standard normal distribution consider log-normal distribution. In log-normal distribution, the stock price always take positive values. In standard normal distribution, stock price can take negative values which is impossible.

We deal with returns, which can be -ve right?

How do I visualize the daily return data in excel? I have calculated the daily return and std deviation for a few other instruments

You can plot a simple line chart to visualize.

Unfortunately Nifty does not allow down loading 4 years data in one shot, and I am unable to edit the formulae to reduce the lines to 253, any solution

Thanks

Yeah, you will have to do this one year at a time.

Sir, I was referring to which method should I use for calculating the standard deviation, did you say to first back test the one you explained in this module in your last response?

Yes, I\’d suggest you back test it once and see how the volatility model behaves before you actually deploy cash.

Thanks for the reply, sir. Which one should I use for volatility calculation if I want to know near which standard deviation is the stock trading (meaning 1sd, 2sd), if I am planning a reversion strategy?

I\’d suggest you look at 2SD and backtest it see what sort of results you get. You can keep tweaking the system from there to arrive at an optimal SD for your risk appetite.

Hi Sir

I understand this method of calculating the annual standard deviation, but I tried calculating the standard deviation of Bosch Limited and there was a difference of 4% from the nse website, and they\’re using a different formula to calculate the standard deviation, which is,[Current Day Underlying Daily Volatility (E) = Sqrt(0.995*D*D + 0.005*C*C)],

They are giving 95% weightage to the previous day volatility. I got this from the daily nse report of volatility. But I\’m unable to understand how are the calculating this previous day volatility? And also which formula should I use the log returns one or this one?

Thanks.

Thats right, exchanges give more weightage to recent data because they need to calculate the margins for contracts. However, the method we are discussing here gives equal weight to all data points and hence the difference.

Respected Sir.

Sir I am very new to trading and some little amount I have invested by reading your fundamental analysis which have grown 5times in 3 year.

Without your guidance I could not have made that money.

Kartik Sir I have a doubt that can I use Heikena Ashi candle for trading Without candle stick ?

Why candle stick is famous ?

I am extremely sorry I am asking in the middle of this chapter.

Very happy to note that, I hope both your understanding of markets and your funds grow over the years 🙂

About Heikena Ashi, I cant really comment as I;ve never used it myself. Thats the reason I\’ve not covered it in TA module as well. Candles is popular because of its simplicity of use.

Good Morning Sir.

Sir I am unable to download the EXCLE.

PLEASE help.

Can you try to downloading from another browser?

Got it sir. It was just a rounding off error

Sure. Glad you figured 🙂

Average = 0.04*252 = 9.66%

Sir when I am doing this calculation in excel I am getting 10.08%,

Not sure, maybe double check the maths?

How to calculate the mean returns for the for the stock.

Have explained in the chapter itself.

Thank you karthik sir this is such a blissful reading experience beautifully crafted

Thanks Syed. Happy learning 🙂

sir i am doing study now so excel sheet is not opening so how to go for average and sd to find out the range

Can you please try another browser?

Hi Sir – How to calculate the daily average for NIFTY in the above example(0.04%) ?

It is clear from prev chapter that the daily volatility can be calculated using STDEV(std deviation).

Thanks

Naveen, are you refering to daily avg returns or daily avg volatility? If its the returns, then calculate the daily return, that will give you a time series of data, calculate the average over it, thats it.

Can you please help with a formula to convert those logarithm percentages to normal percentages, also the sheet link is not working can you please provide the sheet link in comment section.

You can use the exponential function i.e. \’=exp()\’, on excel to convert log to regular values.

Dear Karthik,

Please correct me if I am wrong brother. I am a newbie in finance; reading a lot these days.

But going by your logic, closing price of friday 3 30 should be exact same match as opening price on Monday 9 30?

Plus, Profits and losses are also made on saturdays and sundays (by the company), and implied volatility should also work during market off days(theoretically speaking)!

Volatility is a mathemetical equation. It should be biased towards Holidays!

So thats why I was asking, why sqrt of 252 and not sqrt 365.

pardon my ignorance

Regards

hello dear. I would like to humbly point out that RMS of 365 is 19.1 and of 252 is 15.87. If we calculate annualised and daily volatility by using sqrt252 days, it gives us the wrong answer, while the correct answer can be acheived by taking 19.1 as the factor.

My logic:

Although market trades only functions for 252 days/yr, the share value (conceptually) varies all 365 days in the year. Hence accurate values can be acheived by using 19.1 instead of sqrt252

Regards

Dr Prashant Bansal

Thanks, but how will the stock price vary when markets are closed?

SD = 1.046% * Sqrt (252) = 16.61%

Time last chapter mai 365 liya tha. Es chapter mai 252. Total number of days in a year OR working days of Stock market?? Kaunsa select Lena hai

Go with the first approach.

How to get Daily Average / Mean of stock?

You can use a simple moving average on kite for this, Tarun.

sir using this i have calculted it for nifty bank data 24-09-23 to 24-10-23 i have get the mean of -0.19 and SD is 0.67 here mean is in -ve then i am getting the values like -44.65% etc could you check it clarify it to me

This can happen when the prices have trended down for a few days within the time duration under consideration.

Hi Karthik,

First of all let me congratulate you on completing 13 years of zerodha!!!

I would really appreciate it if you can answer my following questions.

1)When measuring volatility as you mentioned in the module 5 (historical volatility ) to download 1 year data, is that true for every time?

2) if i\’m doing back testing and using 1 year data, for expontial calculation how to chose the spot price?(open/close)

really appreciate your response!!

Thank you 🙂

1) Yeah, gives you a good perspective 🙂

2) Always go for close prices.

Karthik sir, you are truly a great teacher. You taught us differentiation, standard deviation, normal distribution, and much more with so ease.

You should be on one of the school curriculum designers\’ committees.

Thanks for the kind words, happy learning Sujay 🙂

KARTHIK SIR

I have mailed them and they replied that they calculate SD this way:

When the SD setting is set to Fixed SD, the formula to calculate the Standard Deviation is Current Spot Price x ATM IV x 0.01 x square root (days set in Fixed SD / 365 days). To get 1 SD and -1 SD values, the SD is added and subtracted from the current spot price

Sure. Thanks for sharing, I hope that helped you as well.

Sir When we access the strategy builder in Sensibull and create our buy or sell strategy, we can observe that at the bottom of the interface, there are options for selecting either 1SD or 2SD for the specific indices we are trading. However, upon my calculation, I noticed that my results differ from those provided by Sensibull. They do not incorporate the mean into their 1SD and 2SD values, and their calculations seem to be based on monthly data, which does not yield a proper distribution on graph.

Ah, ok. I\’ve not checked their graphs for this. Not sure about this, maybe you can write to them for an explanation as to why monthly data and not weekly. Thanks.

Sir small doubt in key takeaways of the chapter you have written this

Within 1 SD we can observe 68% of the data

Within 2 SD we can observe 95% of the data

Within 3 SD we can observe 99.5% of the data

but don\’t you think it should be

Within 1 SD + MEAN we can observe 68% of the data

Within 2 SD + MEAN we can observe 95% of the data

Within 3 SD + MEAN we can observe 99.5% of the data

The mean is usually really small value, and does not make a big difference in my opinion.

Hello, sir. The Excel sheet link is not working. Could you please provide the Excel sheet?

Can you try downloading from another browser, Rajdeep?

Hi Mr. Karthik,

Thanks for providing the option trading related content.

Can you pls help me? how can i download the excel file from the given link? I am trying but excel sheet is not downloading.

Ajay, can you try downloading this from another browser?

how to convert log % to normal %

Have explained in the chapter itself, kindly check once.

Could you please explain how Daily average mean is calculated. Formula please

We have discussed that in the chapter itself, Vivek.

How to Plot this normal distribution graphs..??

Have explained that in the chapter itself.

Hello sir,

Kudos! I\’ve learnt alot of practical things from you, through these trading series. Thank you giving such an indepth knowledge. I\’ve a question , it\’d be quite helpful if you could help me out.

I\’ve done analysis of volatity of stock market over past 7 years ( by month wise month and year on year). It adhered to volatility points. But I\’m not able to make normal distribution curve, I\’m getting confused what to consider as range for making bar graph?

Glad you liked the content, Archit. There is no hard science as to how to choose the range, number of bins, bin width. You can have maybe 15 or 20 bins and see how the chart turns out and improvise on that.

Hi Karthik, Amazing learnings so far. I just have question. You did a calculation of \”Average = 0.04*252 = 9.66%\” Ideally it should have been 10.08% right?

Ah, looks like a typo 🙂

hi, in that case, where do we stand with vix? it seems that 16.6% (sd) is average vix. but when vix is higher, say 25, since the average is 16, wouldnt this approximation be invalid, or is there an adjustment? also, what is the ideal number of recent data that one should use for this calculation to predict the confidence levels of nifty?

Its not invalid, it just means the fear in the market has increased and therefore the ViX has shot up. There is no adjustment required. Also no ideal number, Madhur.

Sir, i\’ve scratched my head numerous times over converting log percentage to normal percentage? i\’ve tried to search on google, but couldn\’t find a way..

Can you please show me how its done?

Ram, I\’ve explained this in this (or maybe the next) chapter. You use exponential form for this.

I am unable to download the excel which you have shared for the calculation. Is the link still alive?

Yeah, try downloading using another browser Sudip.

Hi Karthik,

Regarding Chapter 17, Volatility & Normal Distribution, i have a query regarding the mean (average) number used. I want to understand the average of data is derived from \”log returns\” or actual daily returns?

Your reply to with with be highly appreciated.

Thank you

I\’ve used both to showcase both techniques. You can use either, Vinit.

and also how did you take bin width value as 50

and one more request from my side sir

can you please make a pdf for sectorial analysis as you have did for other modules and its my humble request that please start a youtube channel and please educate us about these practical scenarios because no course which is collecting more than 1 lakh rupees to teach stock market can beat your content which is provided for free. Thank you for your valuable resources sir it helped me a lot and please do consider my request its my humble request🙏

Ranganath, we have just started the sector analysis module. We will provide the PDF when its all done 🙂

I landed to one of the most prestigious content for option trading. Thankyou for providing such a valuable content sir.

Sir i have a simple doubt

As you have shared Nifty Calculations in the excel format how did you Calculate Bin values and Bin arrays

Glad you\’ve liked the content on Varsity, Ranganath 🙂

Bin values are based on the number of data points. Usually about 25 bins if the data points are between 300-500. No rule though 🙂

Vannakam Guru ,

Very glad to speak to you sir. Little bit confusion about calculation method. I have calculated the normal distribution for nifty last one year period from June 19th 2022 to June 19 2023 with equation of above u have mentioned formulas in MS excel. In your calculation Annual SD ( Annual volatility) is great than Annual Average But i also calculated same formula for last one year returns but I got answers is Annual Avg – 29% & Annual SD – 15%. it seems SD is less than Avg value. This is correct answer or not. For calculate Nifty is likely to be in the range of Average + 1 SD (Upper Range) and Average – 1 SD (Lower Range) \”SD\” is likely to want in Negative value right ? then only we can get lower band value. Pls suggest me how to get exact answer for daily Average / Mean & Daily SD / Volatility.

Sudharsan, how are you calculating the annual average SD? Also, if the returns for a year is negative, then there is a chance for Nifty to goto -ve territory.

Hi,

Recently started reading your modules and find them very interesting and easy to understand. I have one very little query for now, I am trying to get nifty closing prices for last one year in order to calculate Volatility on NSE Website not able to find. However I got the stocks price data on nse website.

Please guide.

Pooja, check here once. https://www.niftyindices.com/

Hello Karthik

I\’m sorry to come back on the same topic.

Firstly, Daily return is different from Daily Average, please comment on this.

Next, as per your example in chapter 17.4 on Daily Average/ Mean =0.04%, there is no clear explanation how is 0.04% deduced. I have cross verified with the Nifty Daily Returns histogram and it results in 0.215% and not 0.04%. Well, I jumped to previous chapters and the example of Billy and Mike makes sense while chapter 17.4 in which Daily Average/Mean is calculated does not explain well.

Can you update this section or explain it in this comment?

Thanks

Varun

Yes, daily return and the average of daily returns are two different numbers.

Lets say your daily returns for 5 days are as follows –

Day 1 – 0.5%

Day 2 – 1.5%

Day 3 – 2.0%

Day 4 – 0.75%

Day 5 – 0.69%

Five-day average return is =

(0.5% + 1.5% + 2% + 0.75% + 0.69%) / 5

=1.08%

Sir,

Could you kindly state if my understanding is correct for the below observations?

1. Daily Volatility of a stock/index = STDEV of past daily annual returns of the stock/index

2. If the above is correct, what should STDEV of past daily annual spot prices of the stock/index identify? can we still calculate the volatility from here?

1) STDEV of past daily returns (not daily)

2) Calculate the daily returns and use the STDEV function on the returns array

The Excel file is not available to download. Please share the same.

Can you try downloading from another browser?

Hey Mr Karthik! I\’m an ACCA student and Im keen to learn about these things.Ill tell u a fun fact,There is a Paper in Professional level of ACCA called AFM which is Advanced Financial Management. There are a few aspects such as Beta,Black sholes Model anol being covered but they were only from the accounting point of view,You are far better than these UK based boards and u indeed simplify topics pretty well .. you are amazing….. My dad use to tell me that the best things in this world are free… I swear that this is the first time I\’m getting it…..

Thanks for that. I appreciate it. I\’m glad you could liked the content on Varsity. And I do agree with what your father says; the best things in life are around us and are indeed free 🙂

Happy learning!

Hmm. Now I got an idea what you mean Sir. Initially I assumed that taking positions early on meant taking the trades slightly before like 2 days earlier for a 4 day SD calculation. But had to say it is quite challenging using SD in hedged strategies since the hedge itself takes away most profits from far out of the money sell positions.

By the way, I\’m currently reading your personal finance and mutual funds module. Your work shows that a non fiction does not necessarily need to be boring. I guess if someone like David Baldacci writes a non fiction it would be analogous to your work. Such a page turner. Please consider publishing books in future and really thank you for helping out slow learners like me.

Thanks for the kind words, Sathish. I hope you continue to enjoy learning on Varsity 🙂 Do let me know if you need any clarifications.

Yes. I totally understand sir. But for instance, if I do the SD calculation for 4 trading days, and try to execute trades early on like 6 days before, although I get fat premiums, won\’t it defeat the purpose of the SD calculation itself?

If you are executing 6 days prior, you need to calculate 6 days SD right?

Thanks for your patience sir. I actually considered that sir. Setting up early on means that the \’time\’ in SD calculation will also increase and so will the number of day\’s standard deviation accordingly. This will in turn increase the range of execution and wont change the profits much since these are very far out of the money. Please correct me if I\’m getting this wrong? This is the problem I faced sir or is it because currently the VIX is ultra low?

Hmm, no. Writing option early means you collect a larger premium owing to heavier time value, right?

If I use SD in hedged strategies like iron Condor(which I mostly use), the rish reward ratio is very poor. Also profits in this case are peanuts. Should I compromise either upper or lower side slightly in this case or how do I approach this?(I\’m asking considering S&R and macroeconomic outcomes)

You can do that, or another alternative is to set up the position early on so that you can benefit from time value.

Hello Sir,

I am a student of your article I don\’t have any idea about stocks after reading all of your chapters and trying out practically in the stock market made me earn more. In this chapter, I just need to know years of historical data needed to calculate mean and standard distribution

Ram, you can start with three years of EOD data. This should suffice, in my opinion.

I am absolutely clear about daily return , SD , Mean

But i am not able to understand how did you get to this ? What is Daily Average

Daily Average / Mean = 0.04%

Daily Standard Deviation / Volatility = 1.046%

Daily average = Mean. The same excel function that I\’ve shown in the chapter helps you calculate the mean.

Your explanations are mind blowing. and too clear .

Glad you liked it, Shubh. Happy learning 🙂

The way all these tutorials are written is SUPERB! There is flow to it which helps in understanding things better. Thank you Zerodha.

Happy learning, Sandeep 🙂

Hi Karthik,

Loved this chapter, for an hour so went back to my school days remembering all those times when Statistics was so fun to learn. Thank you so much for taking your time and taking a step ahead to refresh our basic statistics and relating it to stocks market.

I have a query here, is the statistical way of looking NIFTY important/required when we are looking for intraday opportunities?

With all the crazy global and domestic news happening around (Bank news, war, inflation, recession etc.) I am honestly scared to hold any over night positions in NIFTY.

Can you share what are the things that you consider when taking a trade in options intraday? (Like Price action, technical analysis, indicators, timeframe used, type of news that you consider etc.)

Wanted to hear from you how you do your intraday trade. Hope I am not asking too much, only for learning purpose.

Thank You

It does help to look at Nifty through a statistical lens, irrespective of your holding period, Sai. Yes, I understand the overnight situations can be crazy but that\’s the nature of market. The bottom line is that if you cannot sleep peacefully at night because of an open position, that position is not worth taking, no matter what the expected outcome is.

For intraday, all that matters is how the price action manifests through the day. Keep a close eye on the price development.

Sure. I\’ll start with 5 years data. I previously did with around 13 years data and found that nifty weekly expiring range is between the upper and lower range 9 out 11 times since Jan\’2023. So now I\’ll try with 5 years and maybe try to find if it still fits in. Thanks once again.

Yeah, 13 years data can be a bit dated 🙂

Sir how to find the daily average?

YOu can do it on excel, have shared the steps.

Hello,

I was doing my analysis to learn option trading, so while calculating the standard deviation and the average return for Nifty 50, what should be the ideal size of the dataset, considering it is a daily return. Do we take 20years or 15 years or 10 years of daily return?

Thanks in advance.

I\’d suggest you take 5 years data and slice it down to maybe in 1 year bucket to see how the index has performed. This will be a good starting point.

I am not able to find the way to plot the normal distribution graph.

This entire chapter is about that 🙂

sir if we want to plot a normal distribution graph for any stock or index by ourselves, how should we do it??

I have explained the process in this module itself. You can do it with excel.

Sir I have 2 questions.

1. Why is 252 the time in the case of 1 year calculation and 30 in case of monthly calculation. I thought 252 refers to number of trading days. If so then why number of trading days was not taken in factor for 1 month calculation?(because weekends are holidays)

2. If I had to calculate the same for 1 week, I would be getting only 5 days data since weekends are holidays. In that case, should the time value be 5 or 7?

Thank you.

1) 252 is a day count convention, Sathish. Strictly speaking, if you take 252 days, the number of days should be 22.

2) You can take 5

Sir,

You are calculating from Current market price, if current CMP is all time high the range we calculate comes out to be in the upper side, similarly if current market price is low the range we calculate will be in lower side, both the case results may not be accurate,. Please clarify

Yes, thats possible. Remember, the range is just a predictive tool with some degree of confidence 🙂

hello sir,

I would want to know about the link to the website that you downloaded the nifty daily returns chart. as I am trading in bank nifty and I want to see the daily returns distribution chart.

thank you

Sameer, check exchange website and download the historical data.

Hlo kartik sir

I learnt volatility chapters many time

But I did not come to know how can I use normal distribution curve for trading

. By using the curve how would we decide where to buy and sell

Manish, normal distribution is a concept that will help you understand volatility and trading ranges better. Without an understanding of the normal distribution and its properties, it becomes difficult to figure the associated concepts.

How you have calculated 8337*exponential(26.66%)

By using the exponential function on MS Excel Sohan.

Sir, how do you calculate this?

Upper Range

= 8337 *exponential (42.87%)

= 12800

Even if I add 42.87% on 8337, I get only 11911.

Similarly I dont get the lower range too.

Please clarify the exact method to get the 12800.

Sivakumar, I\’ve explained this in the comments above. Please check.

sir, why are you considering 252 for a year while 30 for a month ? if it is due to nearly 250+ trading day in a year, then why not 21 or 22 for a month? kindly explain.

Thats the right way to deal with the time count convention. 252 is a general convention practise.

Sir very nicely explained, I have never seen explanations of such a critical subject is so easily understandable.

Congratulations and thank you very much for making such a critical subject to make understand so easily.

Happy learning 😉

OK. Thank you. 🙂

Apologies for the repeat question.

Most of the comments with similar questions were hidden by default, so I read them only after I posted my mine.

I wanted to used it in pinescript. I am guessing ta.sma() in pinescript is equivalent to average() in excel.

I\’ve never used pinescript, so cant comment 🙂

> Daily Average / Mean = 0.04%

How is this calculated?

You can use the average function in excel.

Sir, I couldn\’t understand the average return of 0.04%. Could you explain that how you got that figure, or is it just an assumption?

It is just the average of the daily returns, Khitij. Use the \’=avg()\’, function on excel.

Not able to download MS Excel please provide download link to get calculation easy .

Can you try downloading for another browser?

Upper Range

= 8337 *exponential (26.66%)

= 10841

And for lower range –

= 8337 * exponential (-6.95%)

= 7777

Sir here actual calculation come out to be

Upper range = 26.66% of 8337 + 8337 = 10599.6

Lower range = 8337 – 26.66% of 8337 = 7757

Such a huge difference in upper range, please correct me if I am wrong..

Saurabh, we discussed this earlier in the chapter. Can you check the comments once? Thanks.

HI Karthik,

I am trying to calculate the price range of nifty 50 for the past 2 years. I replicated the same procedure mentioned in this chapter. But, the result I got is far away from the actual price for the immediate next year(error percentage of 22~28%). I am not sure if you are following the blog in 2023. But kindly give me reply if you come across this . I can share my excel data over mail.

Thank you

Gopi

Maybe you can share the excel on G drive and share here?

Hello Karthik,

I am unable to download the Excel sheet. Could you please help with that?

Rajesh, can you try downloading from another browser?

How to calculate exponential?

8337*exponential(26.66%)

I am not able to calculate in excel 🙁

You can use this syntax. =8337*exp(26.66%)

Sir,

Under the heading Normal distribution and stock returns Chp 3 ,pg no.10 with the data given.

Nifty CMP 8437 mean 0.04% stdev 1.046%

The calculation given to find upper range and lower range. Given 8337*exponential (26.66%) = 10841 . Sir, please explain the last method used to get the figure 10841

YOu need convert the log returns to a regular scale, hence you use the exponential function, Ajay.

Link to download excel are broken

I guess people can download via different browsers. Can you please try?

Not able to download the excel . How to calculate aver?

Can you try downloading from another browser?

How did ypu plot the Normal Distribution graph? Means X is the change in daily value what it in Y axis

The X-axis represents the percentage change in prices. The normal distribution plots can easily be done on MS excel.

hello sir I need help how did you calculate the average value as i am not able to get the value which you calculated above.

Daily Average / Mean = 0.04%

means nifty\’s daily percentage movemnet divide by total number of days?

am i right????

Yes.

awsome explanation please share your twitter id or any other platform id where you share your views regarding marcket

thankss

Its karthikrangappa on both Twitter and Insta 🙂

Never understood the concept of Normal distribution this clearly. Wonderful and ofcourse the overall explanation was just mind blowing

Glad you found the content useful. Happy learning 🙂

Ok thanks.

Hi Karthik,

For solution 1, I have calculated the Nifty one year range with 1 SD using simple returns(C2-C1/C1) instead of log returns(C2/C1). I got the upper value as 10642 and lower value as 7872 (as against 10841 and 7777). So can i consider these values as more appropriate or is there any reason we should use only log returns.

Yes, Raju.

When a data is not actually normally distributed and it has Skew and Kurtosis, what adjustments I should do while calculating a range so that I can factor in the skew and kurtosis numbers?

Good question, let me check on this and get back.

Thank you for the content , initially i did not get it , but there is a guy called kora reddy .

this guy applies these things and explains much ,after his explanation .

i am able to co relate it.

The assumption that asset prices follow normal distribution can be highly questioned, see for example Mandelbrot (2004) \”The (mis)behaviour of markets : a fractal view of risk, ruin, and reward\”

Prices dont, but we are talking about returns here right?

Solution 1 – (Nifty’s range for next 1 year)

Average = 0.04%

SD = 1.046%

Let us convert this to annualized numbers –

Average = 0.04*252 = 9.66%

SD = 1.046% * Sqrt (252) = 16.61%

&

Solution 2 – (Nifty’s range for next 30 days)

We know the daily mean and SD –

Average = 0.04%

SD = 1.046%

Since we are interested in calculating the range for next 30 days, we need to convert the same for the desired time period –

Average = 0.04% * 30 = 1.15%

SD = 1.046% * sqrt (30) = 5.73%

Dear sir,

please explain how you get the average value of Average = 0.04*252 = 9.66% and Average = 0.04% * 30 = 1.15%.

after calculating the answer is= 0.04%*252= 10.08% &

0.04%*30= 1.20% .

This is little confusing. please explain.

Need to recheck, I hope I\’ve not made any calculation errors.

Tanmoy, I may have inadvertently made a typo here. I need to double-check.

For calculating Annualised SD, why we do: Daily SD * sqrt(time period)?

Because volatility is proportional to sq rt of time.

How can I create the distribution chart in Excel with the data I have? Like the above Nifty Daily Returns distribution chart

I\’ve explained the process. You can use the frequency function for this.

Thanks, Karthik. I fully understood that. However, I was asking about the average ( mean) in absolute terms, that should be constant pivot regardless of you calculating 1SD, 2SD or any more of those varieties. The averages that I got from your calculation ( I calculated it by adding the range numbers and dividing the result by 2) for 1SD and 2SD were different as mentioned in my previous comment. I expected the average to be same, regardless of SD variations, because the mean/average is the constant pivot to find the difference between the distribution values and the mean. Anyways, your write-up is excellent.

The range will change as and when you change the SD, Anant. Happy learning 🙂

Ref: Solution 1 – (Nifty’s range for next 1 year) above: What would be the average (mean) in absolute terms?. From your 1SD calculation above, I get it as 9309 whereas from 2SD cal, I get the mean as 9694?. Can you pls enlighten on this?

So the higher the standard deviation (SD), the higher the range, Anant. Hence, 2SD range will be higher than 1 SD range.

For 95% confidence interval, the values is based in 2 standard deviation but shouldn\’t be 1.96 standard deviation?

For instance:

For 95% confidence level, the upper limit and lower limit should be

Upper Limit: 1.15% + 1.96* 5.73% = 12.3808%

Lower Limit: 1.15% + 1.96* 5.73% = -10.0808%

But, it mentioned that

Upper limit: 1.15% + 2* 5.73% = 12.61%

Lower limit: 1.15% – 2* 5.73% = -10.31%

Which one is correct?

1.96%, 2% is a round off.

Dear sir, I appreciate the method of teaching the calculation of volatility. It is really simple and excellent. In the calculation (In the example of calculation of Nifty range), you have assumed \” Daily average/mean = 0.04. But you have not shown how the daily average / mean of 0.04 is calculated. Please advise how you have arrived daily average /mean of 0.04. Please also advise how to calculate daily average/mean. Please clarify.

d manoharan

There are two steps –

1) Calculate the daily returns of the stock or index you are dealing with

2) Use the excel function \’=Avg()\’, on the returns you have calculated to calculate the average price.

I think I\’ve explained this earlier in this module.

In solution 1 what is the method to calculate average 0.04*252=9.66%

Plz explain how cmp *exponential (x%) is calculated for calculation of price range, and plz also explain how average % is calculated, and how I can calculate volatility for hour time frame or minutes time frame if yes ,how .Will be very thankful

Hey, I\’ve actually posted an extensive explanation for this in earlier comments. Suggest you check that.

Has been and will always be a big fan of yourself and varsity sir. So lucid and simple explanations

Happy learning, Sidharth 🙂

Here you have calculated

Average annuallized = 0.04*252

= 9.66%

But I have multiplied normally but my answer comes out 10.08%

Didn\’t understand your calculation result

How to convert log percentage to regular percentage

By using the exponential function. On excel it is \’=exp()\’. Give the returns within the brackets. Have explained in the chapter.

Sir, why did we use exponential formula instead of straight formula? It would be helpful to understand.

Please scroll up on comments, have explained the logic.

Sir, for the calculation of Upper range (Solution 1 Average + 1SD)

=8337*Exp(26.66%)

=10841

However while calculating this on Excel i got the value to be 10884.10469

The rest of the calculations are good, Can you have a look on this one..?

Ah, possible that this is a typo from my side. Your answer is correct.

sir how did we get that daily average 0.04% and in excel which u shared there is bin array , freq how can we get that values

Dhanush, you can use the =\’Average()\’ function in excel to calculate this.

Sir,

In this context

Upper Range

= 8337 *exponential (26.66%)

= 10841

Instead of solving in this manner, can we solve it by the following way which is discussed in next chapter,

Upper range=8337*(68%+26.66%),

which will be easier.

Sir,Please tell me where I went wrong

Both are alright. I\’ve put an explanation for this in earlier comments. Can you please check that once?

Sir,

How is the daily average given in percentage terms?

Average is a % number, so when you multiply with a number, you do get a % result.

Sir,

For calculating the daily average,are the closing prices of last year till date,been chosen?And also how is the average of daily closing prices of an year converted to percentage terms?

And also 3SD=99.7%,then how probability of black swam or 4SD alone,in this case alone is 0.5%.

And sir last doubt, it\’s a mathematical one,how to calculate 8337 * exponential (-4.58%)

Yes, daily closing price is considered. Also, once you get the average daily return, you can multiply by 252 to get the yearly return. 0.3% actually, not 0.5%. To calculate the exponential value, you can do so in excel.

Hi

I understood that \”Average\” means Daily returns Average.

In case average is (-0.05%) then Lower Range would be higher than Upper range.

Is there any possibility of arriving Average with Minus value.

Please clarify

Ah no, this happens when the stock prices have trended down during the data period you\’ve considered.

Sir in wipro you have calculated daily return and SD

But in nifty you have calculated, daily average / mean.

Have bit confusion about this part sir pls let know

Ah, let me check. Maybe the context is different.

Sir how do we get nifty historical 1years data

Check NSE site, you can download from there.

Hi sir. This is azeesh rahman from Chennai. First of all I would like to congratulate on enlightening me with the concepts of standard deviation and normal distribution.

This may come as a surprise to you, the fact is I am a visually impaired and I studied in one of the premier colleges in India which is located in Chennai. I faced so much difficulties in learning statistical concepts with minimum availability of educational sensitisation to the professors, tools and technologies to teach a visually impaired and a lot more difficulties on my way. I love Maths in my school days and started to hate it in my college just because I am not awarded with the best in class education even in a premier college to learn my favourite subject. But now, with a simple article I am able to understand as well as visualise concepts about normal distribution and standard deviation.

With 99 percentage of confidence in a normal distribution set up, I must say I will score hundred percent in my statistical examinations if it happens today. Anyway I am graduated now. Thank you so much again, you don’t know how much knowledge you have given to me through an article

Azeesh, thanks so much for taking the time to post that message. It really made my day 🙂

I\’m glad you liked the content, and I hope you will continue to enjoy reading on Varsity!

hi sir

i calculated mean value but it got 0.00% for 1 year (took time period was 29-06-2021 to 29-06-2022) nifty50

how much time period we have to take for calculation mean value?

It wont be zero, but near-zero 🙂

hi sir.. how do we get daily mean value for nifty and stocks

Nope, you will have to calculate it.

Hi Sir,

it is really nice explanation on options and greeks. thank you for all your efforts.

could you please share the excel sheets used to calculate Volatility & Normal Distribution ( may be it\’s too late 🙂 I\’m going through these modules, those download links are not working) Than you.

Gopinath, can you try using another browser?

I thank u a lot for providing such valuable knowledge in a simple and charitable way sir

Happy learning 🙂

Is the calculation of average returns / mean just the sum of the ln values divided by their number? I understand and get appropriate values for the Stdev function for calculation of daily volatility, but at times I get negative Daily Average values. Is that normal?

8337 *exponential (12.61%), sir i have not understood this calculation. Please help 🙁

How do you convert log percentage to regular percentage ? Can you explain in little bit more explaination ?

Shubham, I\’have across this and the next chapter. Please do check, also the previous comments please.

You remind me the last chapter of probability in 10th std witch we use to ignore that time….. Now I can understand the value of that chapter….. Thankss u explained in lott simple way

Happy learning, Pankaj!

Sir,

Some questions…

1. While calculating the daily returns of Nifty, you have taken the lookback period from 3/10/2011 till 7/28/2015 which is 5 years.

why have you taken such a long lookback period ?

2. Can we take lookback period to be 1 year only? Will it be sufficient?

Thanks

1) Just to showcase that long term returns are normally distributed

2) Yes, you can.

Thank you so much Karthik sir. Got it.

Sure. Good luck!

Sir, this is referring to section 17.4 – Normal Distribution and stock returns. You have plotted the graph for Nifty returns.

You\’ve calculated the daily average = 0.04% but if we calculate average of these returns it\’s coming to -0.215.

I am taking the returns from the graph that is plotted. -4.17 -3.85 -3.54 -3.22 -2.9 -2.59 -2.27 -1.95 -1.64 -1.32 -1.01 -0.69 -0.37 -0.06 0.26 0.58 0.89 1.21 1.52 1.84 2.16 2.47 2.79 3.11 3.42 3.74. Since i am getting different value I want to know are you using different set of values?

.

The returns that you see are buckets (as explained in the chapter). You need to take the daily returns for this.

Sir can you tell us how you plotted those graphs in excel?? i mean how did you formed that graph?? i mean so we do not have to go through this calculation hassle after plotting this graph i can easily calculate 1sd,2sd in excel just by entering the daily closing price.

YOu can use the STDEV function Vivek. Its fairly easy, I;ve explained in the previous chapters.

Hello Karthik,

Please let me know if \”Daily Average / Mean\” is same as daily return?

where, Daily Return = LN (Ending Price / Beginning Price)

Is Daily Average / Mean calculated the same way?

Yes, that\’s the same thing. The daily mean is the same as the daily average.

Sir, I think the link to the excel sheet is dead, can you please update it…

Hello Sir,

Thank you so much for this amazing content!

I have a question here –

When you calculate this – (I am copying it from your above text) Daily Average / Mean = 0.04% – did you just use = average() and column for average being the % change daily? I am trying to do that and getting very low average, either in +ve or -ve.

I guess I am doing it wrong or something? Because average of absolute % values cant be calculated right?

Thats right. Btw, average returns will be minimal, especially when you run this over large timeframe.

for SD calculation, how much of historical data should one consider?

At least 1 year of data.

Sir,

From where did I get data for preparing Volatility cone.

You can get it from any authorized data vendor (approved by exchange).

Sir for calculation of SD why we sq root 252

hopeing sir gives reply for this. sir, i have calculated range for usd inr using the above used method in nifty. Below i have put a link where i have done the calculation. sir could you please check whether my calculation is correct or not. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1zNgU20GBuCu3MsF_yT7526kc8sgFdiKkGfrL_Snq3lA/edit?usp=sharing .

Karthik sir please 🙏 reply .

Sorry, can you repost your query?

sir, i have calculated range for usd inr using the above used method in nifty. Below i have put a link where i have done the calculation. sir could you please check whether my calculation is correct or not. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1zNgU20GBuCu3MsF_yT7526kc8sgFdiKkGfrL_Snq3lA/edit?usp=sharing .

Sir, I calculated the range for one month i.e., January. How I get benefit from this range as this range is not achieved in the month of January. what should I do for more accuracy of this range.

YOu can use this range to set stop losses/targets and also identify the option strikes to buy and sell.

Sir, I calculated TITAN range for January 2022 and I taken into consider this data from period 1-1-2021 to 31-12-2021. The range I arrived is not achieved in the month of January, even 99.5% confidence. For what purpose I consider this range like for swing, for option. Pls clarify

It is best for swing positions. Don\’t consider this for intraday movements.

Hello Sir, From the above way I calculate reliance range for 30 days taking period from 17-04-2021 to 16-04-2022 and I took 13-04-2022 closing price as CMP and as per 95% confidence reliance range will be 3136.73 & 2227.88 and as per 99.7% confidence range will be 3416.83 & 2045.24. Is this right can you please check sir ?

Yes, not sure if you got that right. At 99% confidence level the range should be winder compared to the 95%.

I have a doubt on calculating daily average , when we calculate daily average return

we have a year of average return which one daily average data we have to prefer

or how we can calculate the daily average return for the whole year ?

To calculate the daily average, first calculate the daily returns and then run on the daily returns, calculate the daily average.

Hi bro. Could you please tell me how to convert the log percentages to normal percentages.

8337 * exponential (-6.95%) = 7777

Please bro explain the above equation.

I don\’t have enough words to thank you bro.

Thanks for educating.

Prathap, you need to use exponential, like the way you have used 🙂

Hi sir,

Volatility and standard deviation calculations Excel sheet was unable to download from given link above.

Hi sir,

Thank you for easy explanation.

however i am unable to download excel formula sheet you provided, can do it again.

Which excel sheet?

Sir Your way of teaching is excellent…

For one year we need to take square root of 252(as no of trading days in a year)..

And for one month we need to take square root of 30(but not 22 or 21 or 20)..

we don\’t need to count the no of trading days when we are taking about one month calculations..?

Thanks, Gaurav. Yes, if you are considering 252, then take 22 days a month just to be consistent.

hello, karthik Sir

in the example above to find the range of nifty

you picked Mean/Average as0.04%

calculating stansdard Deviation And daily return is fine.

how did you calculate mean from daily return?

Anshul, you can use the =AVG() function in excel. Make sure you use this on the stock returns.

From which website I can get average returns of stocks for past 1 year or 3 months?

In the Graph of Daily Returns what are the values on X=-axis and Y-aixs?

Hi Karthick,

Regarding the below query, u asked me more clarity on this

2.I understand that the NSE’s daily and annual volatility calculation is based on the recent data and also the margins, but can use that value to calculate

the normal distribution

My Query:

In NSE site we have the daily and annual volatility data, can we use that data to calculate the normal distribution(Min and Max range) calculation instead of taking the historical data

Prabhu, I\’m not sure if that can be used for normal distribution. This is something I\’ve not thought about. Need to do my own research. If you find any pointers, please do let me know 🙂

Sir I am novice please do not mind answering my question can daily mean be negative if so what would be calculation

It can be Rajiv, especially when the prices are trending down. The calculation remains the same.

we may use bollinger bands for the same calculations in chart form??

Yup or you can even use ATR.

as the NSE\’s website changed (updated) where can we find the daily & annual volatality ?

Not sure where the NSE has the info now, you will have to google up or check with NSE Shiva.

The hyperlinks u gave this chapter are not working to dowmoad the

MS Excel that u have used to make those calculations..

Dear Karthik,

No one can explain these concepts in a simple manner, thanks a lot for this content