It’s the economy, stupid! What do we do with all this money?

We love IndiaDataHub’s weekly newsletter, ‘This Week in Data’, which neatly wraps up all major macro data stories for the week. We love it so much, in fact, that we’ve taken it upon ourselves to create a simple, digestible version of their newsletter for those of you that don’t like econ-speak. Think of us as a cover band, reproducing their ideas in our own style. Attribute all insights, here, to IndiaDataHub. All mistakes, of course, are our own.

People still seem reluctant to invest in India…

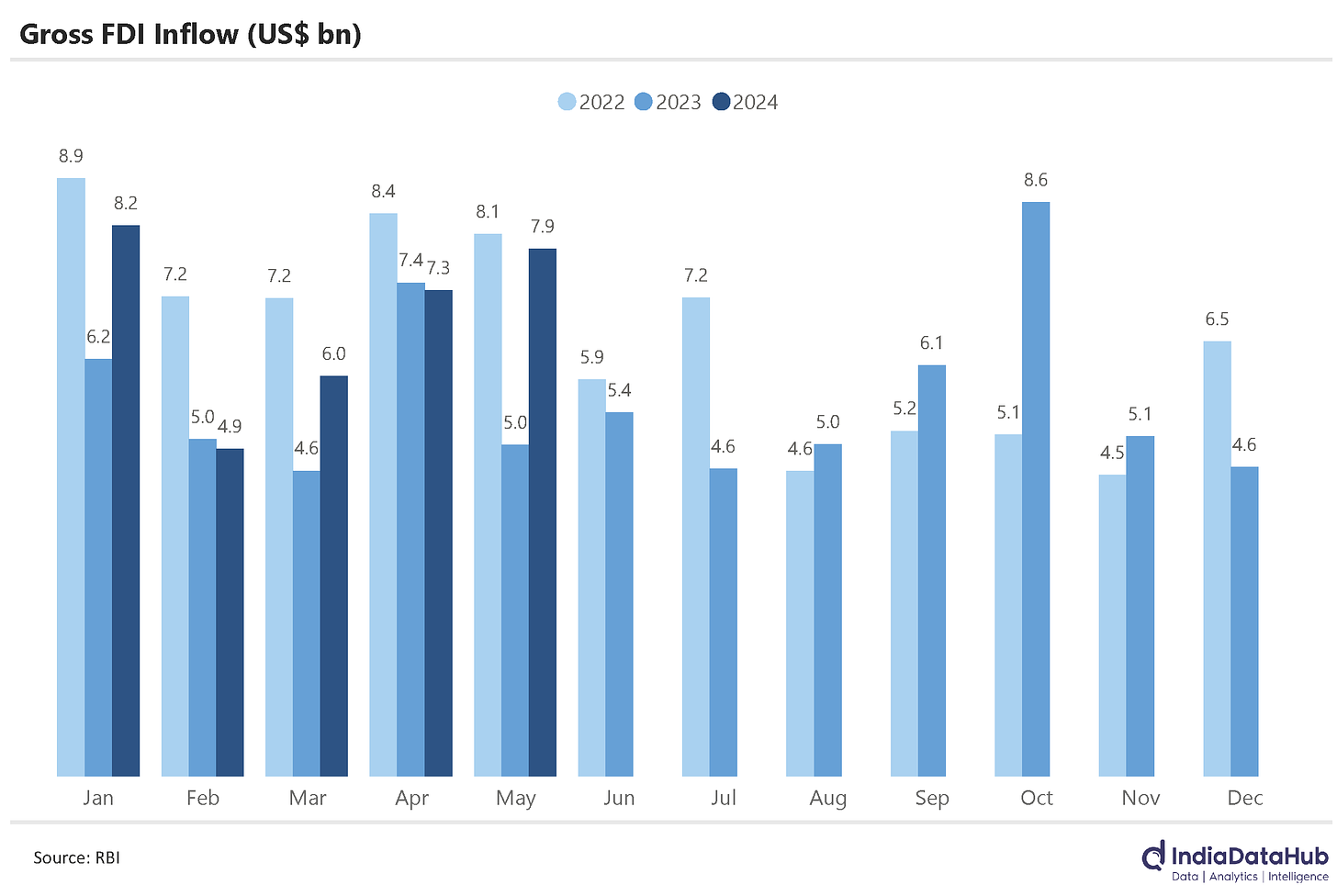

Long-time readers of this series probably know that we’re very interested in the decline in the FDI we’ve been receiving. There’s some good news on that front, this week. FDI flows have been inching up over the last few months. Through April and May, the first two months of this financial year, India got 20% more FDI than it did in the same months last year. Similarly, March also saw an uptick of 20%.

Are we out of the weeds, then?

Well, not quite. While FDI has grown since last year, that isn’t saying much. Last year was atrocious, when it comes to FDI. We got far less FDI last year than we did in 2022. Frankly, we’re still well short of 2022 — FDI in the first five months of this year 15% below the same months from 2022.

Let’s dig a little further into what we mean by “India” receiving FDI, though.

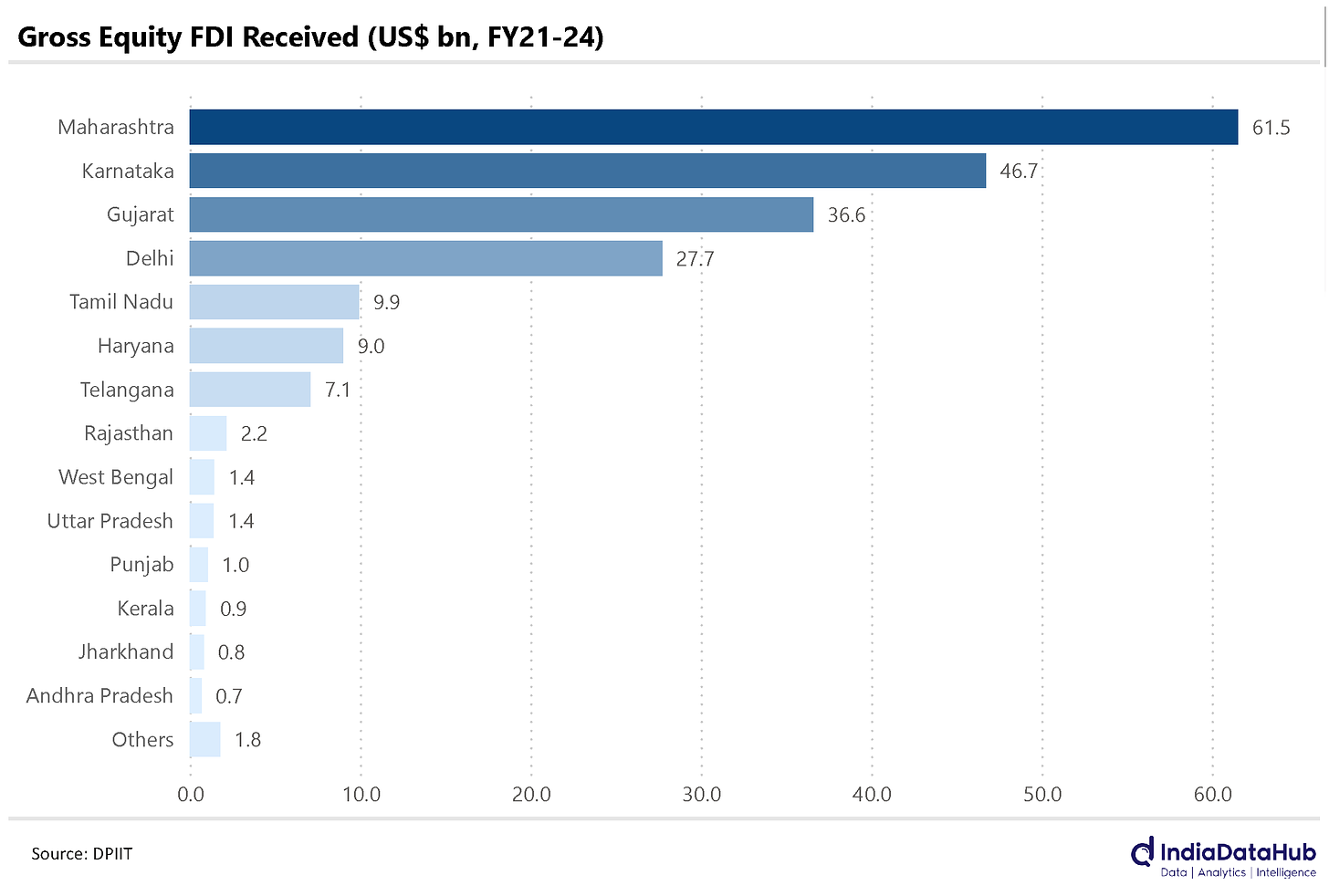

Foreign investors don’t spread their money across India equally. Most of our country simply isn’t attractive enough for that. There are a handful of Indian states that attract tens of billions of dollars in FDI, while the vast majority of states practically get nothing.

Frankly, if you follow any amount of business news, you can probably already guess how the numbers break down. Of the $200 billion we got in foreign investment in the last four years, more than $160 billion, or 80% of the pie, has come into just four states — Maharashtra, Karnataka, Gujarat and Delhi. Most of the rest went to Tamil Nadu, Haryana and Telangana.

All our other states and union territories — a giant part of the country housing almost a billion people — receive almost nothing. The graph below should tell you about the scale of the disparity between our states’ investment climes. Pretty sobering, huh?

… But money keeps pouring in

Other from direct investments, though, we’re bringing in all sorts of money from abroad. Survey this:

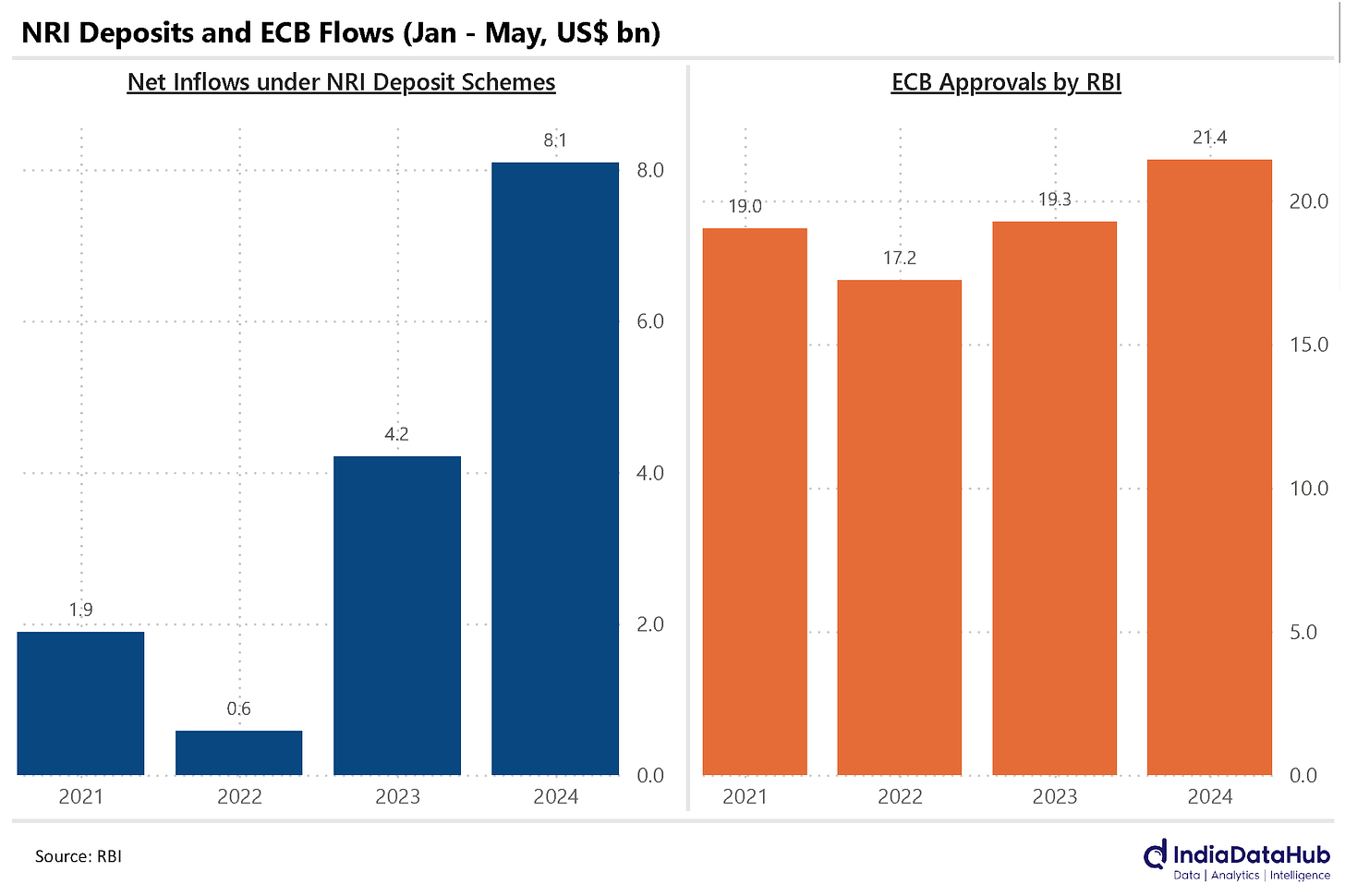

- We received $1.6 billion in NRI deposits this May. In the first five months of this year, we received $8 billion as NRI deposits — the most we’ve received since 2015. By the way, that’s twice what we got last year.

- Indian corporations have been borrowing heavily from abroad. Our ‘external commercial borrowings’ for the first five months of this year were $20 billion — 10% higher than last year.

- After pulling out considerable sums of money in April, FPIs are interested in India once again. So far, in July alone, we’ve received more than $5 billion.

At this run rate, we’ll pull in much more than last year’s ~$ 85 billion in capital flows by the time this year is through.

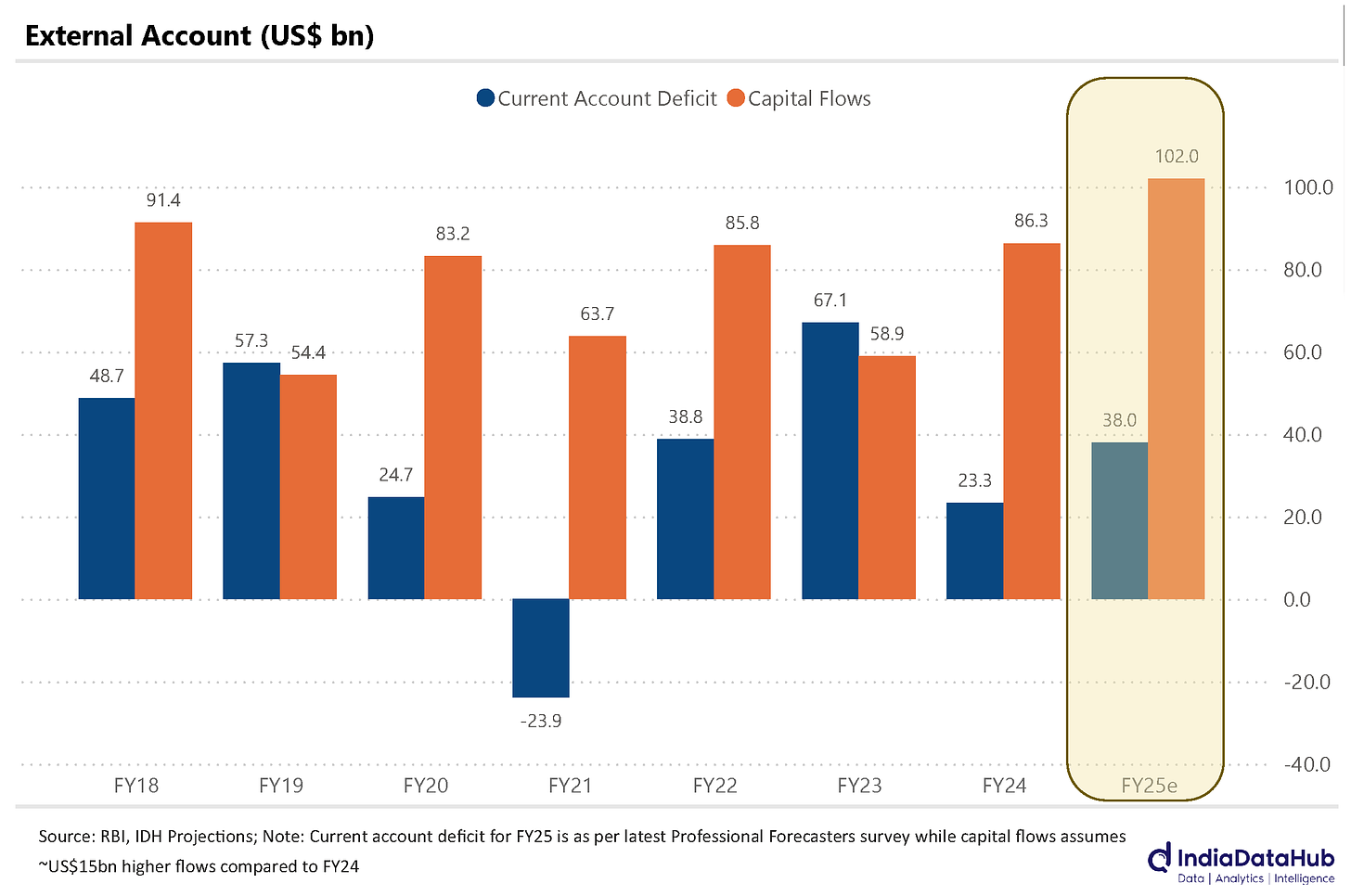

If you’re wondering, capital flows are when money comes into a country with string attached. Look at everything we’ve talked about above. Investments, bank deposits, loans — these are all cases where money enters India, but with the understanding that it could eventually go out some day.

Contrast this with the ‘current account,’ where money is given away with no such strings. When we buy oil from Saudi Arabia, for instance, the money we pay is gone for good. We regularly import more things than we export, so we usually run a current account deficit. (That’s why the March quarter’s current account surplus was such a big deal.)

Our high capital inflows this year will almost certainly eclipse whatever money leaves our current account this year. In all, our balance of payments (the current and capital accounts, taken together), as things are going, will cross $60 billion this year.

So, what do we do with all this damn money?

With all this money coming in, there are two things the RBI can do.

One, it does nothing. It simply lets market forces go the way they will. When money flows into India, basically, foreign currency is first converted into the Rupee, and then those Rupees go to individual Indians. And vice versa. When we have a ‘balance of payments surplus’, essentially, more people want to exchange their foreign currency for Rupees, than wanted to sell Rupees for foreign currency. In other words, there is more demand for the Rupee than supply.

And so, the Rupee grows more expensive. But if the Rupee is more expensive — if it’s costlier to exchange it for any other currency, think of what happens to anything we export. Anyone who buys our exports will now have to spend more to give us the same number of Rupees. In other words, our goods become more expensive for no fault of our own.

Alternatively, the RBI can take a bunch of Rupees, and go buy some foreign currency (or, more likely, some assets denominated in a foreign currency) with it. That currency sits in its reserves, as some sort of a national savings account. At the same time, the supply of Rupees increases, and the price of the Rupee stabilises.

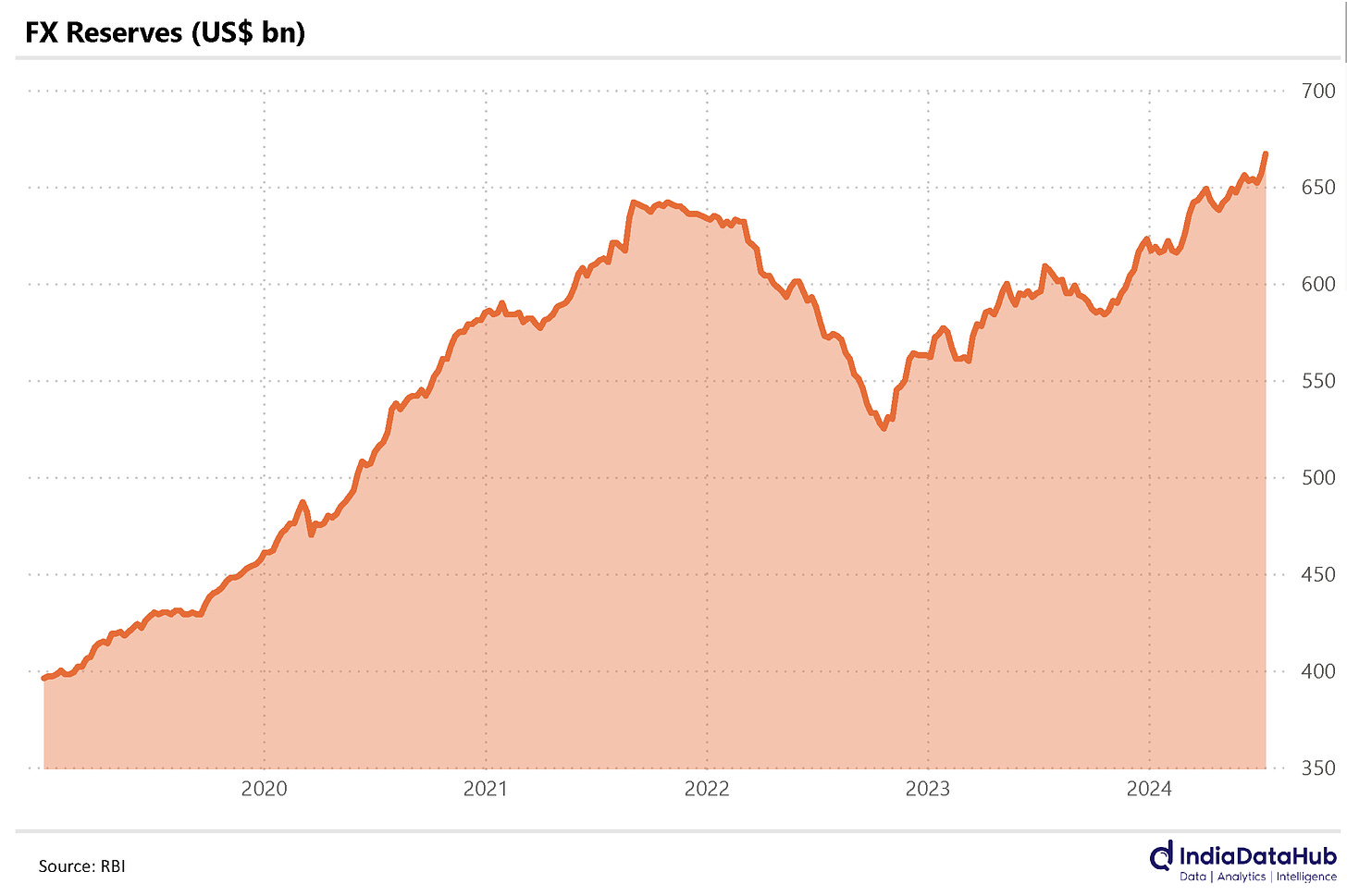

Right now, the RBI has chosen the latter option. In the first two weeks of this month, its reserves were up by $15 billion.

Foreign exchange reserves can help you with a lot of things. As we’ve written before:

“The country can use them to buy its own currency in international markets, to make its value go up. It can use them to pay off debts. If things go seriously wrong, it can use them to import essentials. They don’t have a single, defined purpose – they help a country ride out any monetary shocks it would otherwise face.”

Ideally, you want to have enough foreign reserves that you can import everything you need for a whole year, in case things go horribly wrong for some reason. RBI’s reserves, at $ 667 billion, can cover eleven months of imports. There’s a good argument that it should collect more reserves… but there’s a flip side.

Where does the RBI buy foreign currency? From banks and financial institutions. If you’re exporting something to Portugal, say, and get paid in Euros, your bank will change it to Rupees for you. Then, it can hold on to those Euros, and sell them to the RBI if asked. When the RBI buys that foreign currency, it gives the bank Rupees.

In doing do, the RBI adds more money to the system. The bank can lend that money out to someone, from where it can enter the economy. Guess what happens next? We’re back to our old favourite in this series: inflation.

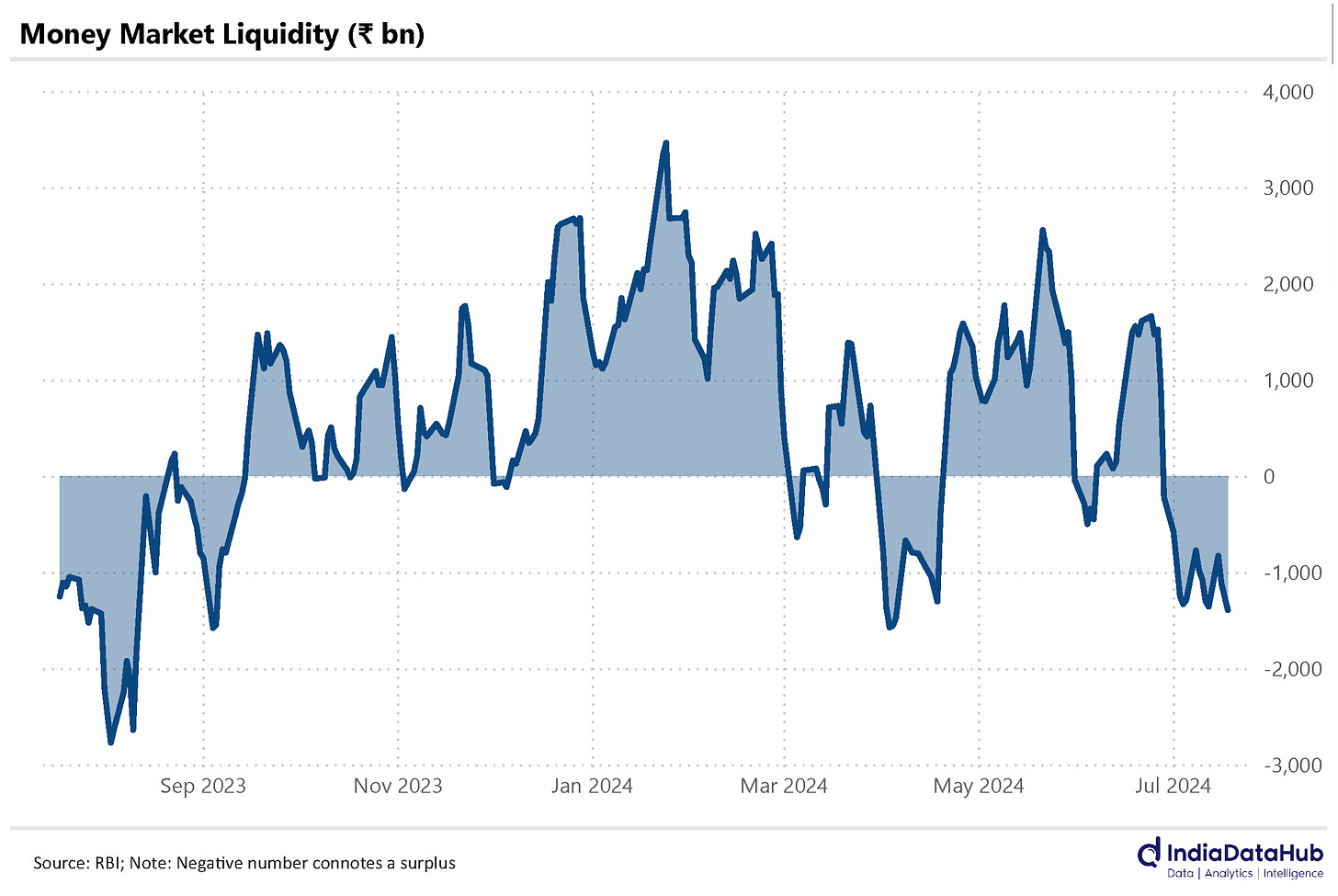

That’s happening at this very moment. Since the start of this month, money market liquidity is in surplus. That is, there’s excess money in the system. Banks, for instance, are lending to each other at rates lower than the RBI’s repo rate. They only do that when they have extra money lying around.

Sopping this liquidity up, now, is a new headache for the RBI. To do so, it’ll have to give the banks something — some sort of government security — in exchange for all the money they hold, and at attractive enough rates.

It can take up ‘Open Market Operations’, where it sells government securities it holds to banks. But this will cut down on the interest income it earns. Or, it can create new securities and sell them to banks, by issuing ‘Cash Management Bills’, or some other bonds under its ‘Market Stabilisation Scheme’. But that, in turn, means that the government has to pay more interest going ahead. Whatever approach the RBI takes, there will be costs. There are no easy options.

You can, indeed, have too much of a good thing. That’s as true of money as it is of anything else.

A meh month for trade

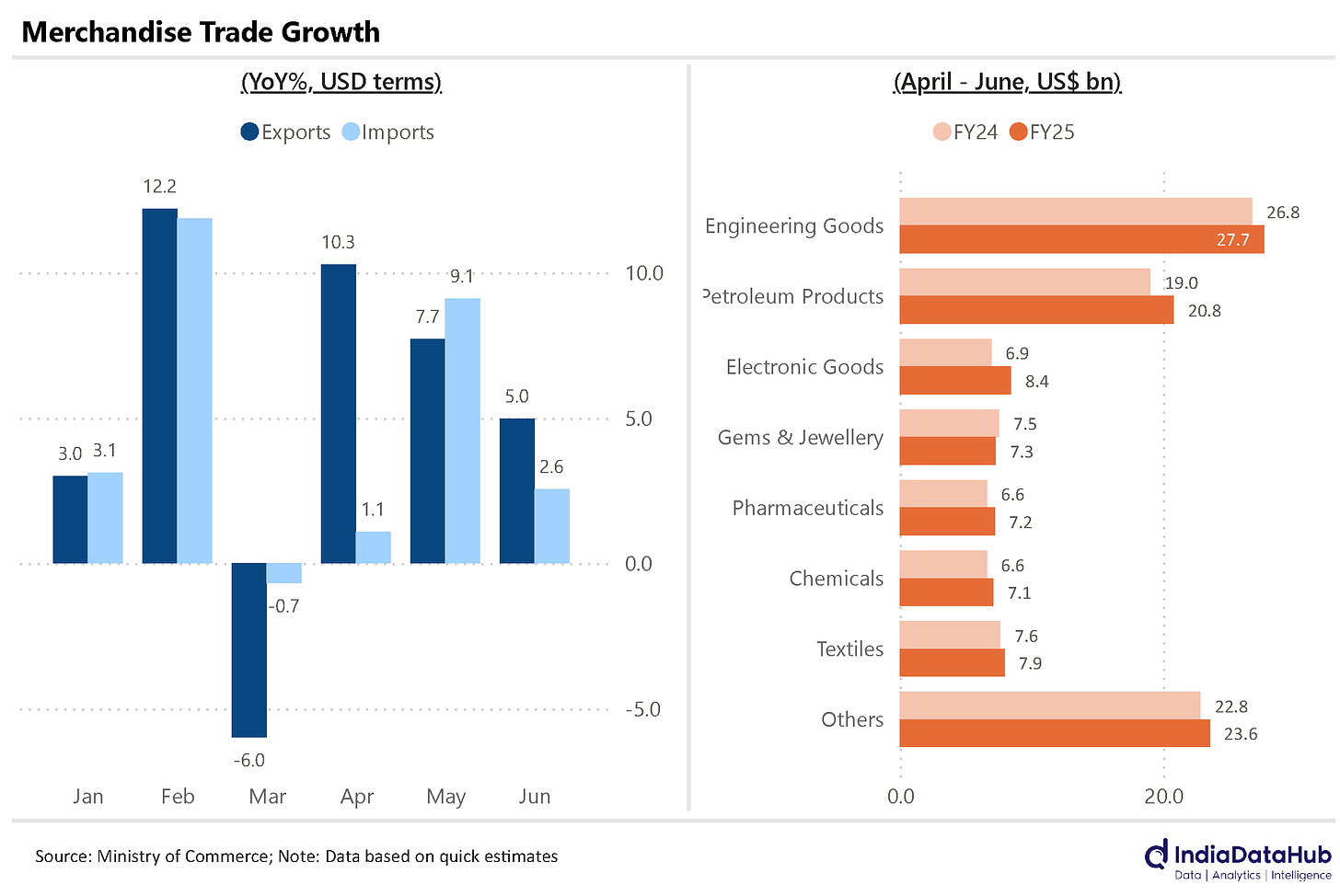

Sometimes, economic indicators just make you go ‘meh’. That’s exactly how the trade data for June looks. Both our imports and exports grew slightly — in the low single digits — from June last year. Our imports grew slightly faster than our exports, though, so on the balance, our trade deficit was 10% higher than June last year.

Amidst the meh-ness, there’s some straight-up good news: our electronics exports keep shooting higher. This June quarter, they were 20% more than in the same quarter last year. In fact, one-fourth of all our new exports over this period were for electronics. They’ve brushed past textiles and gems to become our third biggest export, after petroleum products and engineering goods.

All our other exports, though, have barely grown in the single digits.

China goes slow

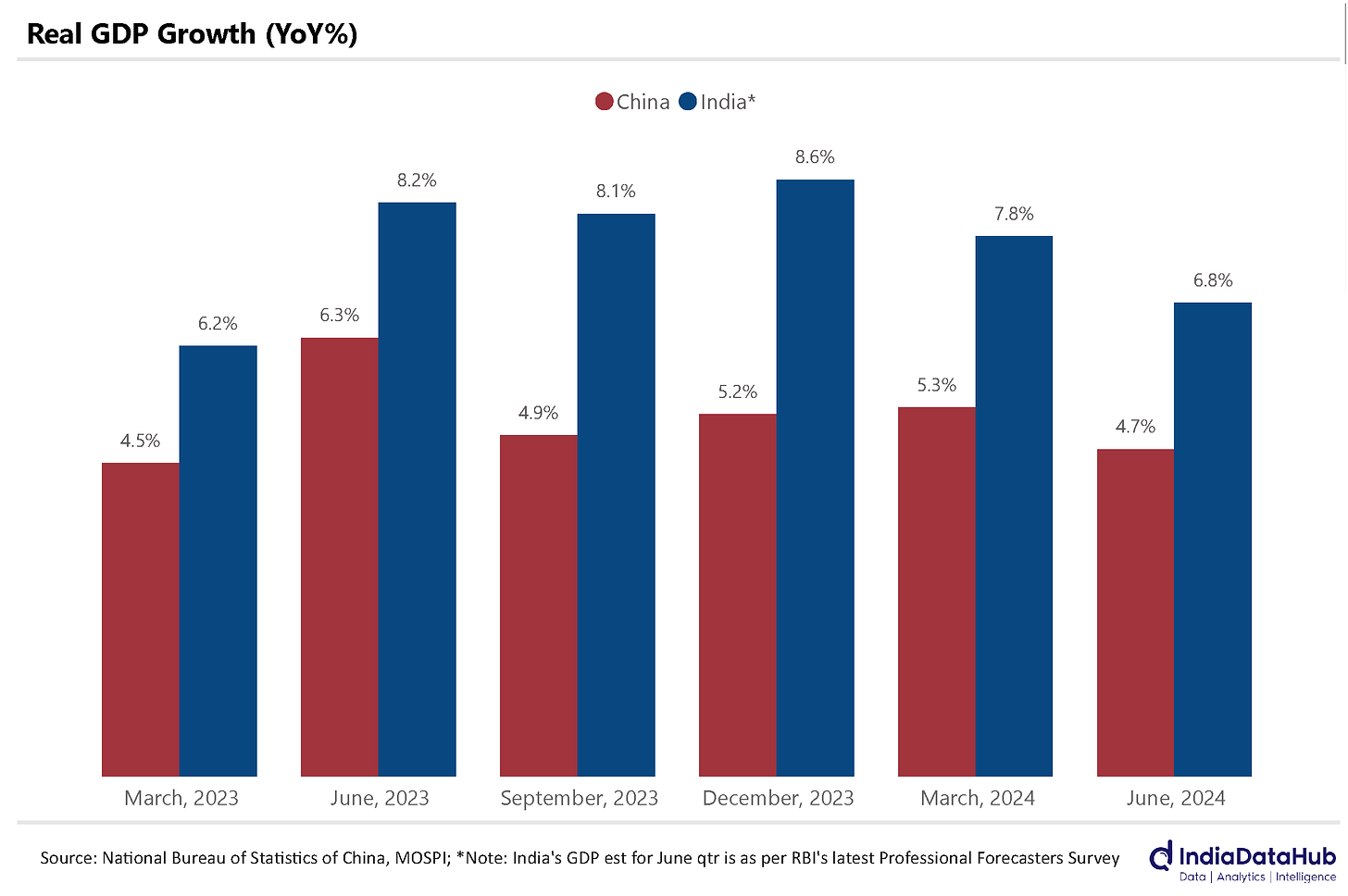

China thought it would grow by ~5% in the June quarter this year. At 4.7%, it’s fallen well short of its target. This is the slowest growth the economic behemoth has seen in five quarters.

Many of China’s old sins are coming back to haunt it. The country propped up its real estate market for over a decade, until it turned into a bubble. That bubble popped in the last couple of years. And this quarter, the real estate industry has registered a 5% decline.

India, meanwhile, is on track to grow its GDP by ~7% in the quarter. That’s one more quarter where the Indian economy outperforms China.

That’s all for the week, folks. Thanks for reading!

An excellent article