It’s the economy, stupid! Repo rate redux

We love IndiaDataHub’s weekly newsletter, ‘This Week in Data’, which neatly wraps up all major macro data stories for the week. We love it so much, in fact, that we’ve taken it upon ourselves to create a simple, digestible version of their newsletter for those of you that don’t like econ-speak. Think of us as a cover band, reproducing their ideas in our own style. Attribute all insights, here, to IndiaDataHub. All mistakes, of course, are our own.

Another meeting with no cuts

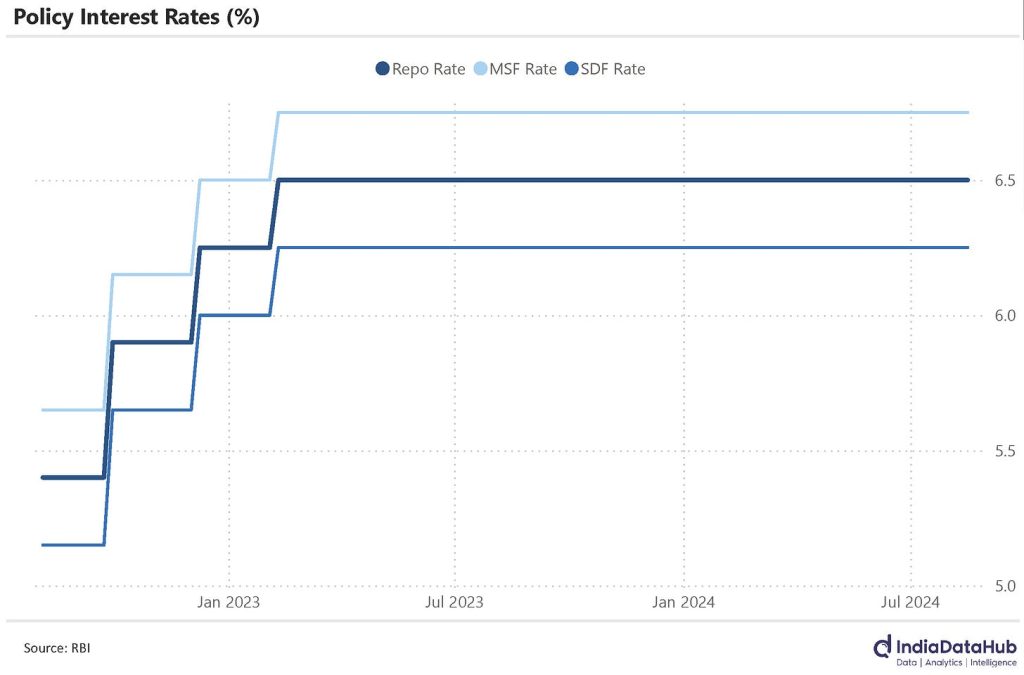

The RBI’s Monetary Policy Committee met last week. And yet again, it decided to keep its repo rate exactly where it was. The repo rate is, in a sense, the cost of money for the economy. It’s the interest rate at which banks can get money from the RBI. When it’s low, banks borrow indiscriminately and loan money out for cheap. When it’s high, they hold off. Now, the RBI’s repo rate has been relatively high — at 6.5%, in fact — since last February. All commercial loans in the economy are effectively given at a higher rate than this. The RBI has kept the rate up there once again.

This isn’t the unanimous view of the committee. Like the last time, two of its members — Jayanth Varma and Ashima Goyal — were in favour of a cut. They were outvoted 4-2, though, which is why the RBI is keeping rates unchanged. Its policy stance, which signals how it might behave going ahead, also remains unchanged. (Officially, it’s stance is “remain focused on withdrawal of accommodation to ensure that inflation progressively aligns to the target, while supporting growth,” which is a complicated way of saying “we’ll keep rates high, but not so high that growth suffers”.)

The RBI is basically walking a tightrope. On the one hand, it needs to make sure there isn’t too much money in the system, or it’ll drive up prices. On the other, it needs to ensure there isn’t too little money in the system, or the economy will stagnate.

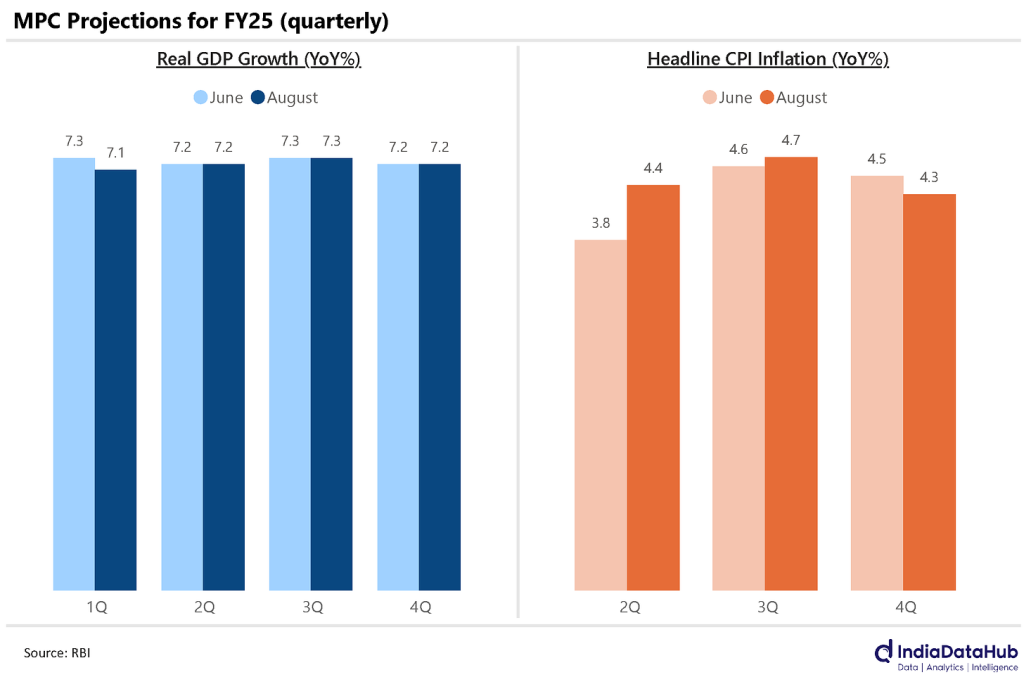

This equation is shifting slowly for the RBI. It thinks India is growing slower than it anticipated. For the first quarter of this year, it downgraded its growth projections by 0.2%, from 7.3% to 7.1%. If the decline continues, it might push the RBI to reconsider its stance. Inflation, however, remains a concern. The RBI sharply increased its expectations for inflation in the second quarter of the year — from 3.8% to 4.4%.

Clearly, there isn’t enough that pushes the RBI to make a change just yet.

The nightmare case

The RBI’s main job is to control inflation. In doing so, however, it follows a key directive: it has to ensure monetary stability, as we’ve mentioned before.

This is clearly something RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das has been thinking hard about. In his August statement, he mentioned three major risks to our monetary stability:

- One, banks are finding it hard to gather funds. As other asset classes — such as mutual funds — become more attractive, people aren’t keeping their savings with banks. Banks, therefore, are being pushed to tap into other sources of money — like non-retail deposits, or other borrowings — which are more expensive, and perhaps riskier as well. If things go wrong, this can trigger serious liquidity problems, leaving banks unable to pay their own lenders even when they have enough assets on paper.

- Two, unsecured personal loans have been growing. That is, ordinary people are increasingly living on borrowed money, without putting any collateral at stake. The RBI has taken some steps to curb this — and indeed, the growth of these loans has moderated in places. But there are many segments where these loans continue to grow. In a crisis, this may push many regular people to default on their loans and become insolvent — causing financial distress for people that are the least capable of handling it. Meanwhile, without collateral, banks will be left high-and-dry as well.

- Three, collateralised lending is growing in an unchecked manner. These are loans people take after keeping something valuable, like their home or gold, as collateral. The problem, unfortunately, is that many banks aren’t adhering to the regulations on this — for instance, they aren’t ensuring that their collateral is large enough to cover any default.

At the root of all these problems is too much credit. To Governor Das, banks are giving away too many loans in an unchecked manner, which could create many major problems for our economy. This makes its decision on rate cuts more complicated. If the RBI cuts its repo rate, borrowing money will become even more attractive, and these problems will grow worse. Meanwhile, as more money enters the economy, other assets will go up in price, pulling even more people away from keeping money with their bank.

So, despite everything, the RBI may choose to stick with the status quo.

Private auto sales recover, commercial vehicles still lag

For a couple of months, automobile sales were down in the dumps. Thankfully, they seemed to recover in July. Before we go any further, though, here’s why they’re important, as we wrote back in March:

“People always need vehicles. But vehicles are huge purchases, not made on a whim. People buy them when they have money to spare and feel confident that things look good in the foreseeable future. As a whole, then, Indian automobile sales tell us how good Indians feel about their economic prospects.”

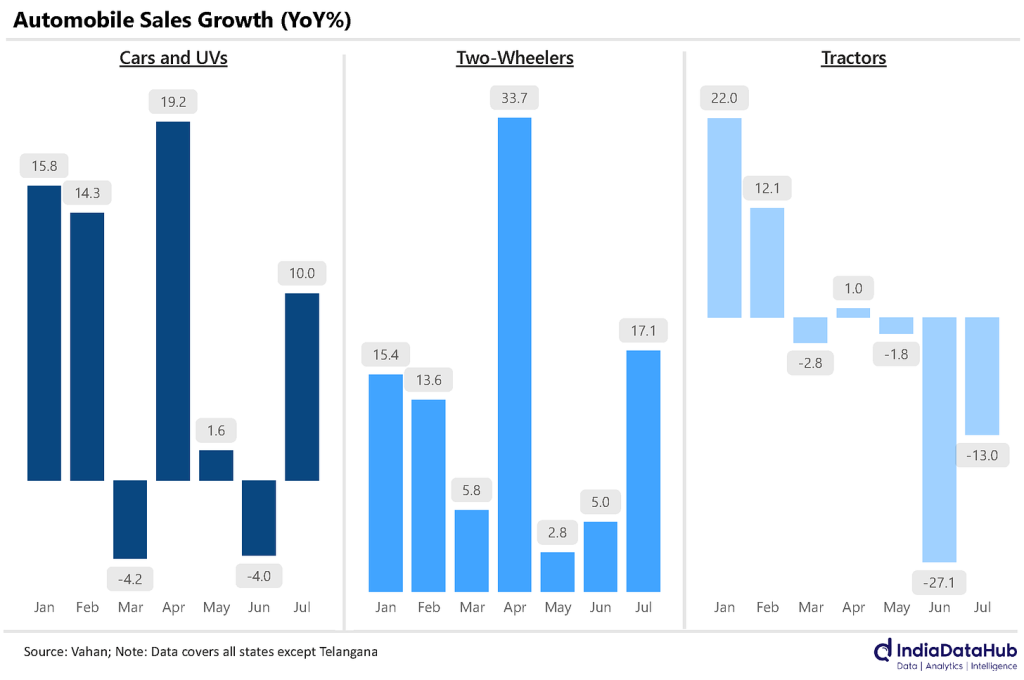

July saw a strong rebound in sales of personal vehicles. People bought 10% more cars (including utility vehicles) and 17% more two-wheelers than they did last June.

On the other hand, commercial vehicles haven’t yet recovered to the same degree. Tractor sales have declined once again — by a massive 13% against last July. Goods vehicles also saw a meagre 3% growth year-on-year.

Renewables power on

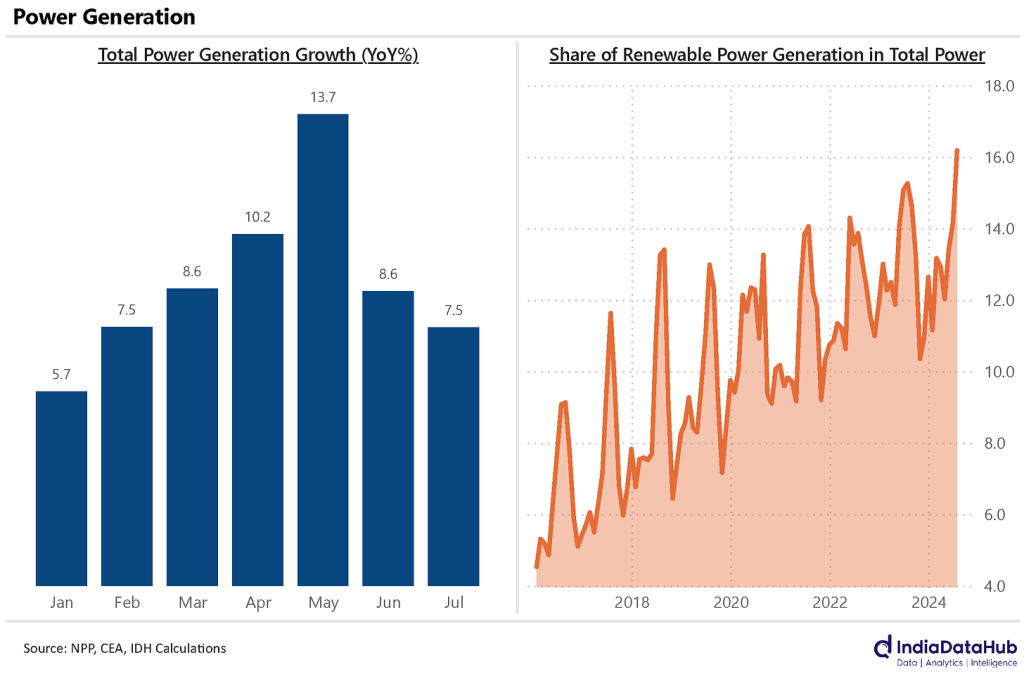

In July, power generation grew slower than it had in recent months — at a 5-month low of 7.5% above last year.

The twist, though, lies in renewables, which are at a 5-month high. Power generation through renewables was 14% higher than last year. In all, renewables made for a record 16% of all power generated in India. That’s the highest share it’s ever had.

Rising reserves

India’s foreign exchange reserves are up again. They touched US$ 675 billion in the week ending on August 2, rising by US$ 8 billion through the week.

As we wrote recently, though, increasing one’s foreign reserves comes at a cost:

Where does the RBI buy foreign currency? From banks and financial institutions. If you’re exporting something to Portugal, say, and get paid in Euros, your bank will change it to Rupees for you. Then, it can hold on to those Euros, and sell them to the RBI if asked. When the RBI buys that foreign currency, it gives the bank Rupees.

In doing so, the RBI adds more money to the system. The bank can lend that money out to someone, from where it can enter the economy. Guess what happens next? We’re back to our old favourite in this series: inflation.

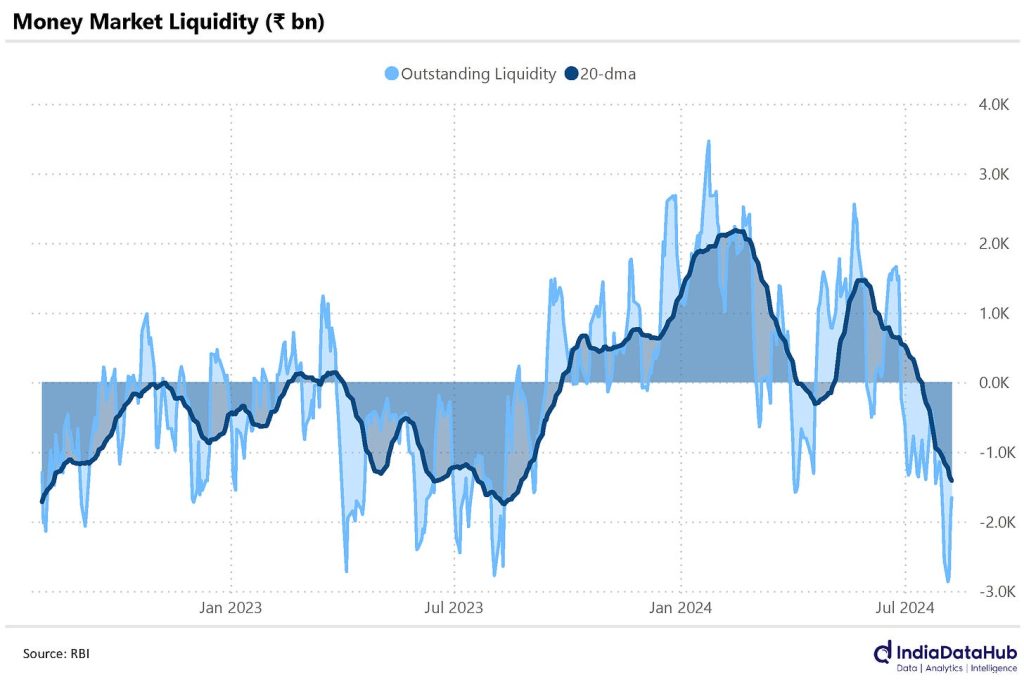

That’s happening at this very moment. Since the start of this month, money market liquidity is in surplus. That is, there’s excess money in the system. Banks, for instance, are lending to each other at rates lower than the RBI’s repo rate. They only do that when they have extra money lying around.

India has added $30 billion to its foreign exchange reserves in 2024. A lot of this money is finding its way into the economy. Money market liquidity is in a surplus. Over the last month, it has averaged at ₹ (-)1410 billion — that is, banks have almost US$ 17 million more than they need in the short term. This is the highest liquidity in more than a year.

This, along with expectations of a rate cut by the US Fed, has pushed down bond yields. Before we carry on, let’s take a detour to see what this means.

See, when someone’s issuing a bond, they fix the price at which it’s first sold, and the price at which it’ll be redeemed. Everything else depends on the market. If I’m selling you a bond, I’ll tell you something like: you can buy this at 100 bucks, and three years from now, I’ll pay whoever’s holding the bond 130 bucks. If you buy it, in a sense, you’ve loaned out 100 bucks at a ~9.14% interest rate.

Now, let’s say, one year on, you learn something horrible about my financial health, and you’re worried that I’ll never pay you back. Instead of worrying for another two years, you try selling the bond for whatever you can get. You find someone who’ll pay you 90 bucks for the bond, and salvage a decent bit of your invested money. But think of what they gain: if I pay them at the time of redemption, they’ve put in 90 bucks, and received 130 in just two years. In a sense, they’ve made a two year loan of 90 bucks, at ~20% interest.

Take another case: let’s say there’s a terrible bear market immediately after you buy the bond, and people start looking for anywhere that they can still park their money without losing it to inflation. And so, one year into your purchase, someone’s willing to pay you 115 bucks for your bond. You’ve earned a neat 15% return within just a year. At the time of redemption, two years thereafter, they’ll get 130 bucks for the 115 they put in. They’ve effectively given a 115 buck loan, at an interest rate of ~6.32%.

You see, in other words, what you pay for a bond determines how good the returns are. The ‘yield’ of a bond — the interest you get — is inversely proportional to the price a bond is selling for in the market.

When banks have a lot of extra money to spare, they start buying government bonds. At the same time, America is cutting interest rates, so people are looking elsewhere for some return — including Indian government bonds. With all these new buyers, the price of the bonds is going up. Conversely, their yield is coming down:

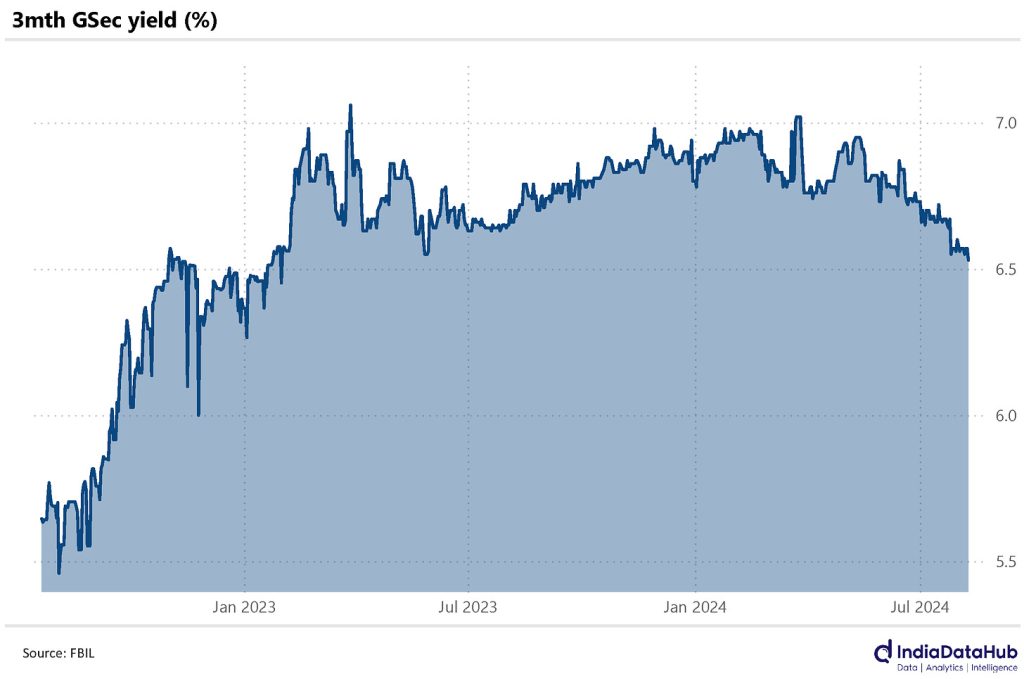

- The yield on 3-month government securities (i.e. government securities that can be redeemed in three months) has fallen to 6.5% — the lowest since early 2023.

- The yield on 10-year government securities has fallen below 7% for the first time in more than a year.

Now, the repo rate sets the baseline for interest that one expects. It’s practically the cost of money in the economy. If you’re investing your money anywhere at all, you’re taking some risk, and you probably want to be compensated for it. So, you’re probably looking for a return that’s higher than the cost of money. This is why government bonds are usually a little more expensive than the repo rate.

Which is why it’s interesting that the yield on 3-month G-secs is at 6.50% — which is also the repo rate. It’s as though investors are buying G-secs with no risk premium at all. When this happens, it’s usually because people expect rates to fall soon. It looks like the markets are gearing up for a cut in the repo rate.

But, from what the RBI’s saying, that doesn’t seem likely at all.

Elsewhere in inflation

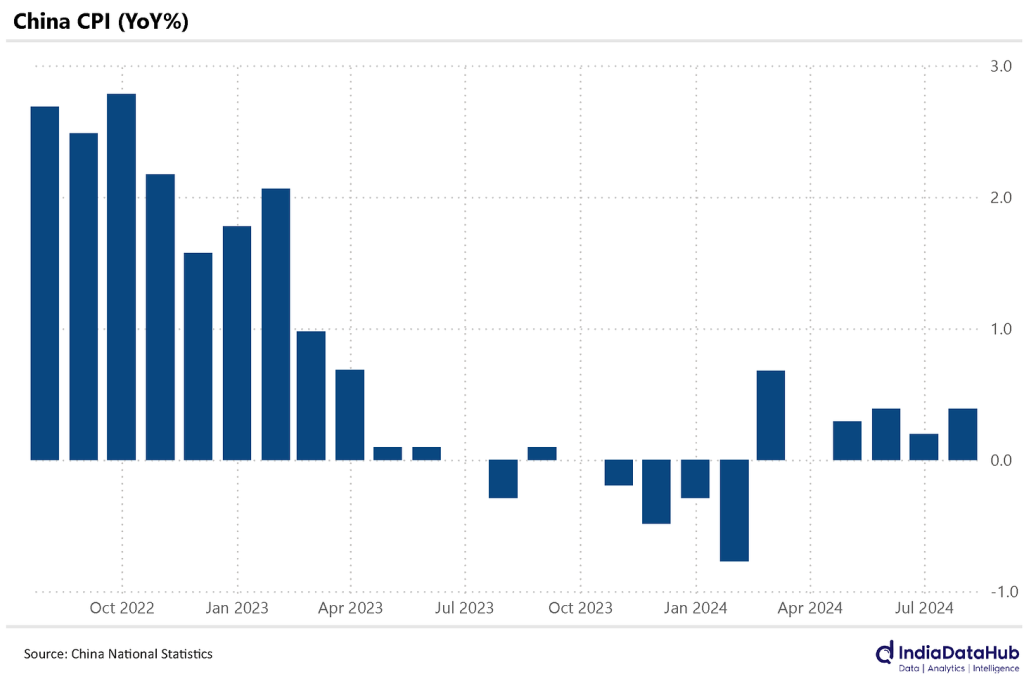

After a long time when people refused to buy anything and prices stayed flat, China’s finally got some inflation going. The country’s CPI went up slightly — to 0.5% in July, from 0.2% in June. Here are the details:

- The prices of food, tobacco and alcohol shifted marginally: by 0.2%. Meat, though, was an outlier. Livestock prices were up by 4.9%, while pork prices rose 20.4% since last year.

- Other supplies rose in price by 4.0%.

- Meanwhile, the prices of services, education, culture and entertainment went up by 1.7%.

China’s exports have grown a little slower than experts thought they would — at ~7% over last year. Meanwhile, its imports have also surged by 7% year-on-year. As a result, its trade surplus has declined slightly — to $85 billion, from nearly $100 billion last year.

Meanwhile, Turkey’s inflation is finally dropping! Turkey’s going through a prolonged economic nightmare, when prices were climbing by more than 70%. At that rate, if your lunch cost 100 Lira today, it would cost twice as much — despite no improvement whatsoever — by December 2025. In July, Turkey’s inflation fell by 10% from June — to 62%. (For context, India’s total inflation hasn’t crossed 10% in more than a decade.)

Turkish prices are still rising at a dramatic rate. It’s only that the rate of price rise has come down. Even if it brings its inflation back into a normal range — as President Erdogan has promised by the end of the year — once prices rise, they rarely fall again. Unless Turkey sees an equally dramatic deflationary episode in the future, the new, higher prices will probably get locked in forever. The low prices of the past will not return again.

This episode came about because President Erdogan decided to go against conventional economic wisdom — pioneering “Erdoganomics,” an experiment where Turkey tried fighting inflation by flooding the economy with money. Naturally, that didn’t work. This is yet another reminder that no matter what one thinks, there’s only one test of how the world works: it’s the economy, stupid!

That’s all for the week, folks!