It’s the economy, stupid! Money enters India, but not its government

We love India Data Hub’s weekly newsletter, ‘This Week in Data’, which neatly wraps up all major macroeconomic data stories for the week. We love it so much, in fact, that we’ve taken it upon ourselves to create a simple, digestible version of their newsletter for those of you that don’t like econ-speak. Think of us as a cover band, reproducing their ideas in our own style. Attribute all insights, here, to India Data Hub. All mistakes, of course, are our own.

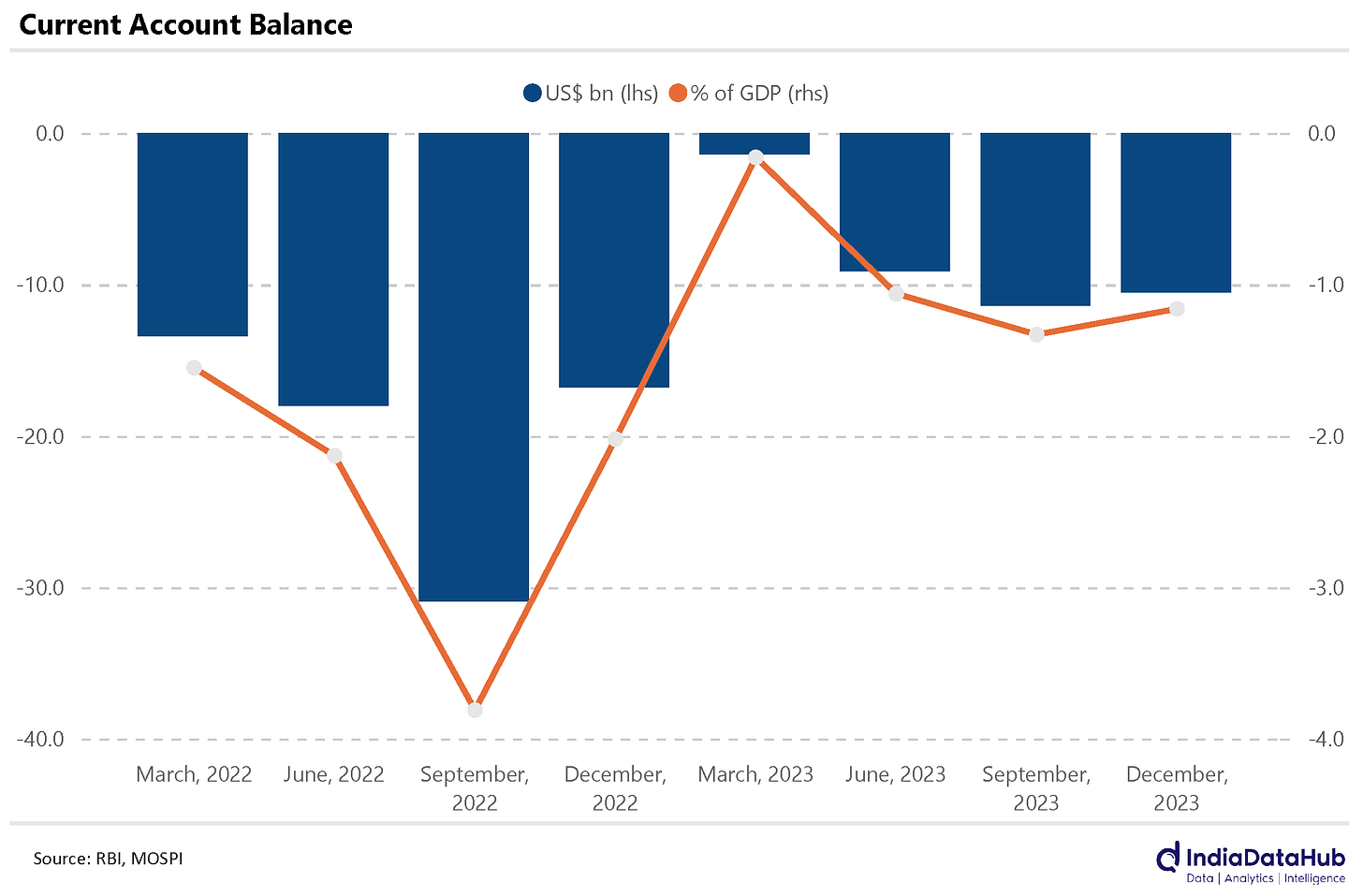

Here’s some good news to begin with: India’s current account deficit fell in the third quarter of this year, to 1.2% of the GDP.

Try again. Like a normal, non-boring person this time.

Mm-hmm, sure. We’d touched on this a couple of weeks ago:

We maintain a record of the money going in and out of the country. There’s usually two ways this happens:

-

- One, money goes in or out of a country cleanly. That is, whoever receives money gets to keep it, no questions asked. This usually happens when you sell something and pocket whatever was paid for it, although there are other ways in which this happens. The record of all this movement of money is the Current Account.

- Two, money can go into a country and create an asset or liability. You could give someone a loan in another country, and they have a duty to pay it back. Or you could invest in another country, and have rights over something there. This is money given with strings attached. We record such movements of money in the Capital Account.

The two make the two halves of a country’s ‘Balance of Payments’.

We usually run the first of these – the current account – on a deficit. That is, we usually send out more money than we earn. That’s the curse of having to import most of our fuel.

The good news, though, is that this deficit is falling. In the third quarter of FY 2023 (or the three months between October and December 2022), it was at 2% of our GDP. In the second quarter of FY 2024 (that is, the three months between July and September last year), it was at 1.3% of our GDP. In the third quarter of FY 2024, it’s fallen further, to 1.2% of our GDP.

(If you’re wondering, by the way: a ‘financial year’ – FY for short – is a year-long period that ends on March 31. For instance, FY 2024 began on April 1, 2023 and went on till March 31, 2024.)

In the space of a single year – between the third quarters of FY 2023 and 2024 – our current account deficit has dropped from US$ 17 billion to US$ 10.5 billion.

Fantastic! What are we doing right?

Well, we’re selling a lot more services than last year. While our earnings from other sources haven’t gone up too much, services have single-handedly closed down almost half our deficit.

That’s that for the current account. There’s another side to one’s balance of payments, however.

Yeah, the capital account?

Exactly! Not bad, I’m impressed.

I mean, you just mentioned it.

Ahh, right. Anyhow.

While money leaves India under the current account, capital is coming in at an even higher rate. For five straight quarters, we’ve had a ‘balance of payments surplus’. That is, on the whole, more money has entered India than has left it for 15 months on the trot.

All this money goes into our foreign exchange reserves. From a couple of weeks ago:

A country’s ‘foreign exchange reserves’ work a little like its savings. Like your personal savings, these reserves can have many uses.

The country can use them to buy its own currency in international markets, to make its value go up. It can use them to pay off debts. If things go seriously wrong, it can use them to import essentials. They don’t have a single, defined purpose – they help a country ride out any monetary shocks it would otherwise face.

This has created enough demand for the Rupee that its price has remained stable in currency markets. We’ve explored this before in some depth.

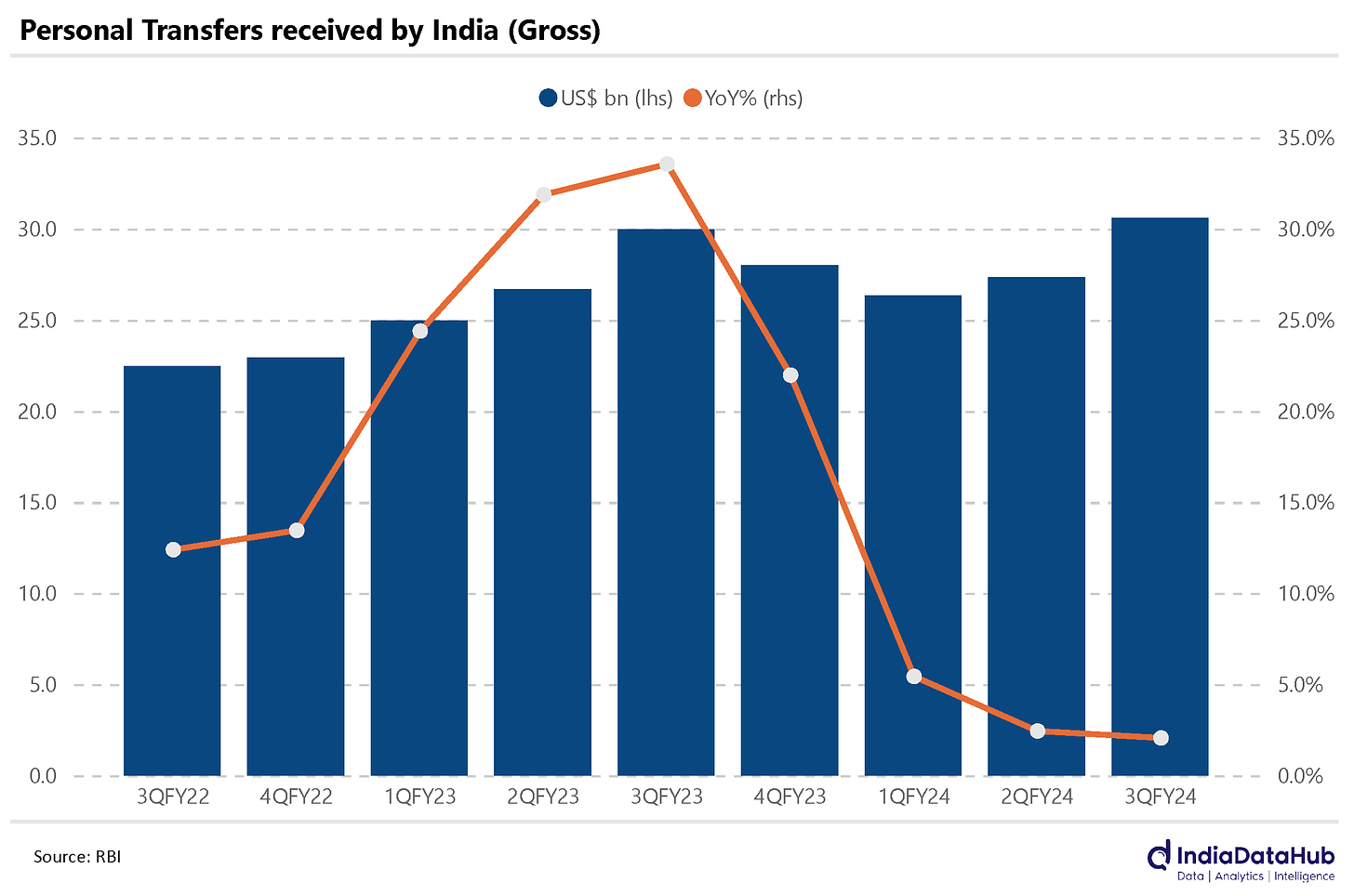

In the quarter between October and December last year, India received US $ 30.6 billion in ‘remittances’ – the most it has ever seen. That is, Indians living abroad sent more money back home over the quarter than in any quarter before.

Are you saying there’s a good side to brain drain after all?!

Nope, I’m not. That’s contested. Some people think the most skilled emigrants send the least money back home. Perhaps we need to send out fewer software engineers and more construction workers.

And besides, this isn’t a bonanza we can count on forever. While total remittances have increased, they haven’t grown nearly as fast as they did before.

Ah. So there’s a catch.

The world is messy. Suck it up.

Here’s the issue: remittances were 25% higher in FY 2023 than in FY 2022. They had grown by double digits in the year before that. In FY 2024, however, they’ve barely grown. We’re only seeing meager, low single-digit growth.

This could simply be a base effect issue – with last year’s growth being so dramatic that we struggled to cross it this year. But this is something to look out for.

On other news: you know how we’ve been talking about the RBI’s repo rate for a bit? There’s news on that front: the RBI’s MPC is currently meeting for its next decision on rates.

Oh! Big moment? What do you expect?

Nothing, most probably. There’s unlikely to be much action at this meeting. We covered this in detail last week, but here’s a recap: we’ll probably see rates being cut in the next three months or so. India’s inflation seems under control, while high interest rates are beginning to pinch our economy. There’s no tearing hurry for the RBI to make changes right away, however. It might take time setting expectations in the market so that the transition to lower interest rates is smooth. We’ll probably only see anything notable at its next meeting.

That’s what the market expect as well. Again, see last week’s edition for details. Fundamentally, though, if people think money will be in short supply in the near future, they are reluctant to part with it. As a result, short-term securities are only sold when yields rise – that is, when they promise higher returns. This rise in yields is particularly stark in government securities, because there are few other things that impact their prices.

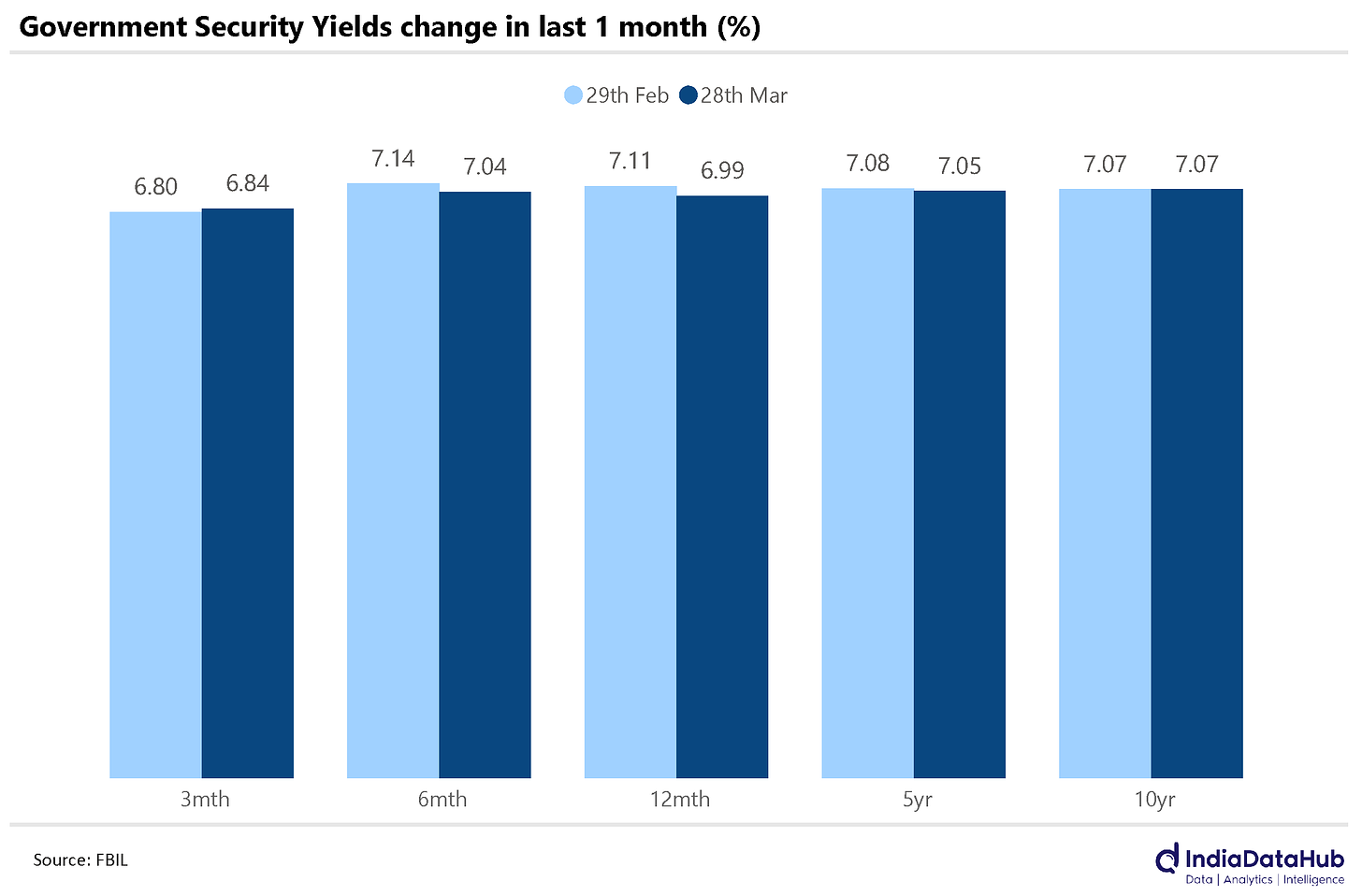

That is happening right now. Yields on treasury bills with a three month-maturity are pretty much where they were last month – in fact, they might have even risen marginally. Evidently, people still want a premium on the money they invest. They don’t think money will become easier to come by any time soon, whether or not there’s an RBI meeting.

A little longer out, though, things change.

You mean the things on this graph other than the left-most rectangles?

Precisely. Look at that graph closely. Look at the bars for securities that’ll mature in six months. Or a year. Do you notice something interesting?

They’ve fallen a little this month, I guess?

Right! But that’s not all, is it?

Yields for securities maturing in three months have increased. Yields for securities maturing after that have fallen. Imagine a line that connects the three interest rates. This line would have been rather curved last month. It’s ‘flatter’ now.

Is there a point to imaginary curves flattening? Sounds like looking for shapes in clouds.

Not at all. See, this shape has real meaning.

It’s simple, really. If you’re investing in securities that mature in three months, you don’t get to see your money back for another three months. Six months, and you don’t get to see your money for twice as long. One year, and your money is away from you for four times as long. In the meanwhile, if you need your money urgently, that’s simply too bad. Nobody’s under any compulsion to pay you before the securities mature.

And so, the longer you’re locking your money away for, the better you want the deal to be. Life will keep hurling bouncers at you either way. The more time you spend away from your money, the more likely you are to be in a situation where you need it. So you need something extra to convince you that committing your money for longer is a smart idea. Going just by this, you’d expect our imaginary curve to keep sloping upwards. When it doesn’t – when the curve ‘flattens’ – you have to wonder why.

Here’s one answer: the market thinks money is in short supply now, but may be available more freely a few months down the line. This might happen, for instance, if the RBI cuts its repo rate in a couple of months. Over the next six months, you might conclude that money will be hard to come by for the first three months, but will flow readily after that. In such a case, perhaps, you’re fine with earning less of a premium when you’re giving out your money for longer – after all, that additional time isn’t really adding much risk for you.

Perhaps this is why the yield curve is flattening at the ‘shorter end’ – the market is expecting a rate cut in the next quarter or two.

When repo rates are high, borrowers take a hit. Obviously. High repo rates make loans more expensive, after all, so those who take loans must pay more.

Banks take a hit too, however, which is less obvious. The way that repo rates operate ensures that banks get caught between the RBI and their borrowers, crushing their profit margins like grain in a chakki.

Explain?

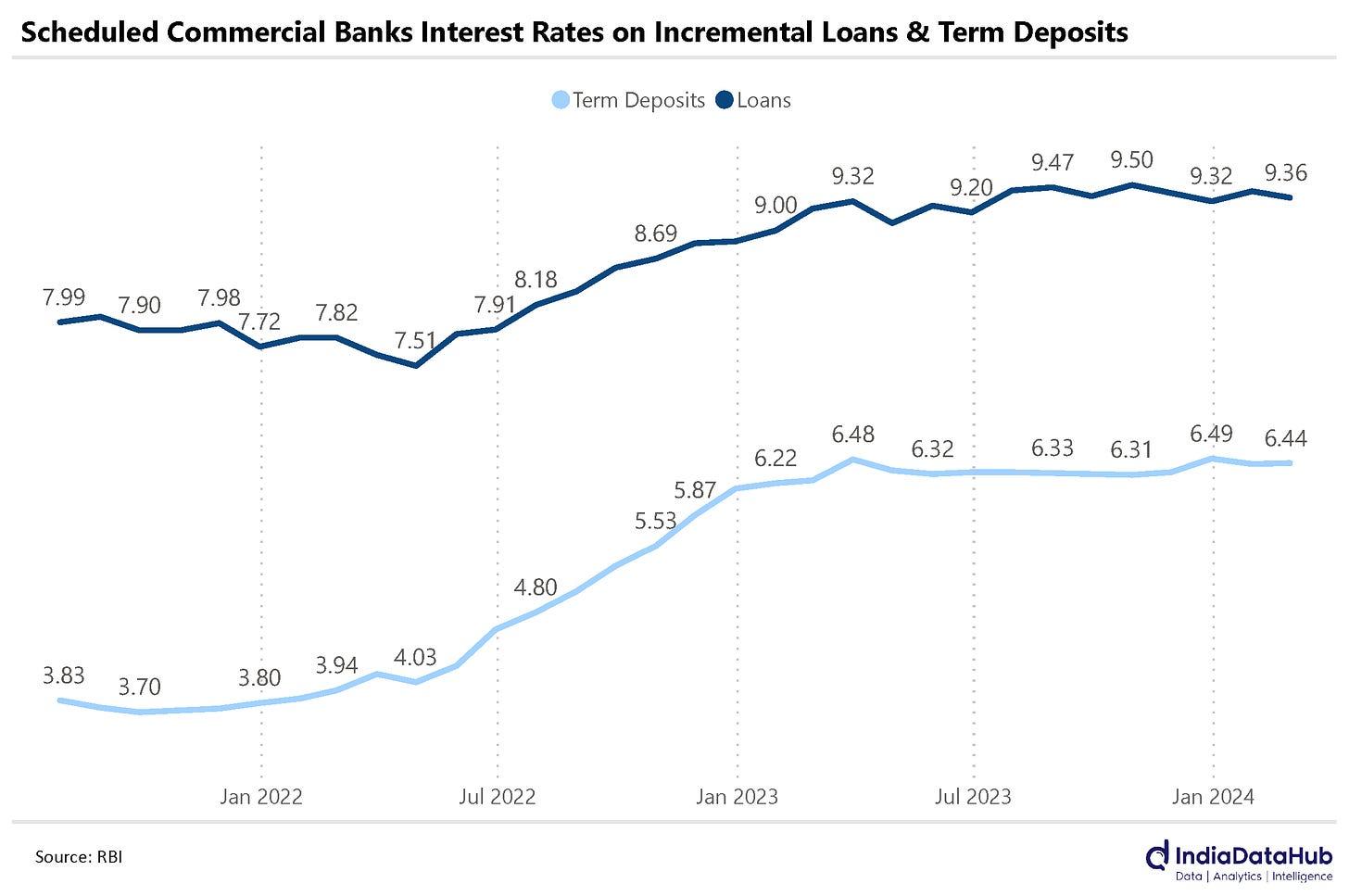

Take the last few years. The RBI’s Monetary Policy Committee increased its repo rate by 250 basis points (normal people, that’s 2.5%) since April 2022. As a result, fresh money became more expensive for our banking system.

To a bank, there are two ways to generate the money that you loan out. One, you can borrow from other banks or the RBI at a rate that hovers around the repo rate. Two, you can loan out the money that people deposit in their bank accounts. Since April 2022, the first of these options has become 2.5% more expensive. Logically, then, banks would try to shift to bank deposits. It’s cheaper, after all. That’s what banks did. They began incentivising people to deposit more money with them by offering better interest. Eventually, the interest they paid on deposits grew by 240 basis points at an average (normal people, that’s 2.4%) – only marginally less than the amount by which the repo rate grew.

But why is that an issue? They could just make loans more expensive, right?

Yes, they could. And they did.

The catch is: they couldn’t increase the interest on loans by as much as the repo rate increased. Lending remains a competitive industry. The more expensive loans are, the less likely people are to take them. There’s no point charging a high interest if nobody agrees to borrow from you. And so, on average, banks are only charging 185 basis points more for loans than they were before.

That is, they are now paying 2.4 – 2.5% more for money, but are charging only 1.85% more when they loan it. The difference between the two – the ‘spread’ – was compressed. For every rupee lent, banks are earning back less interest than before.

If the rates are cut down, though, you might see the tables turn.

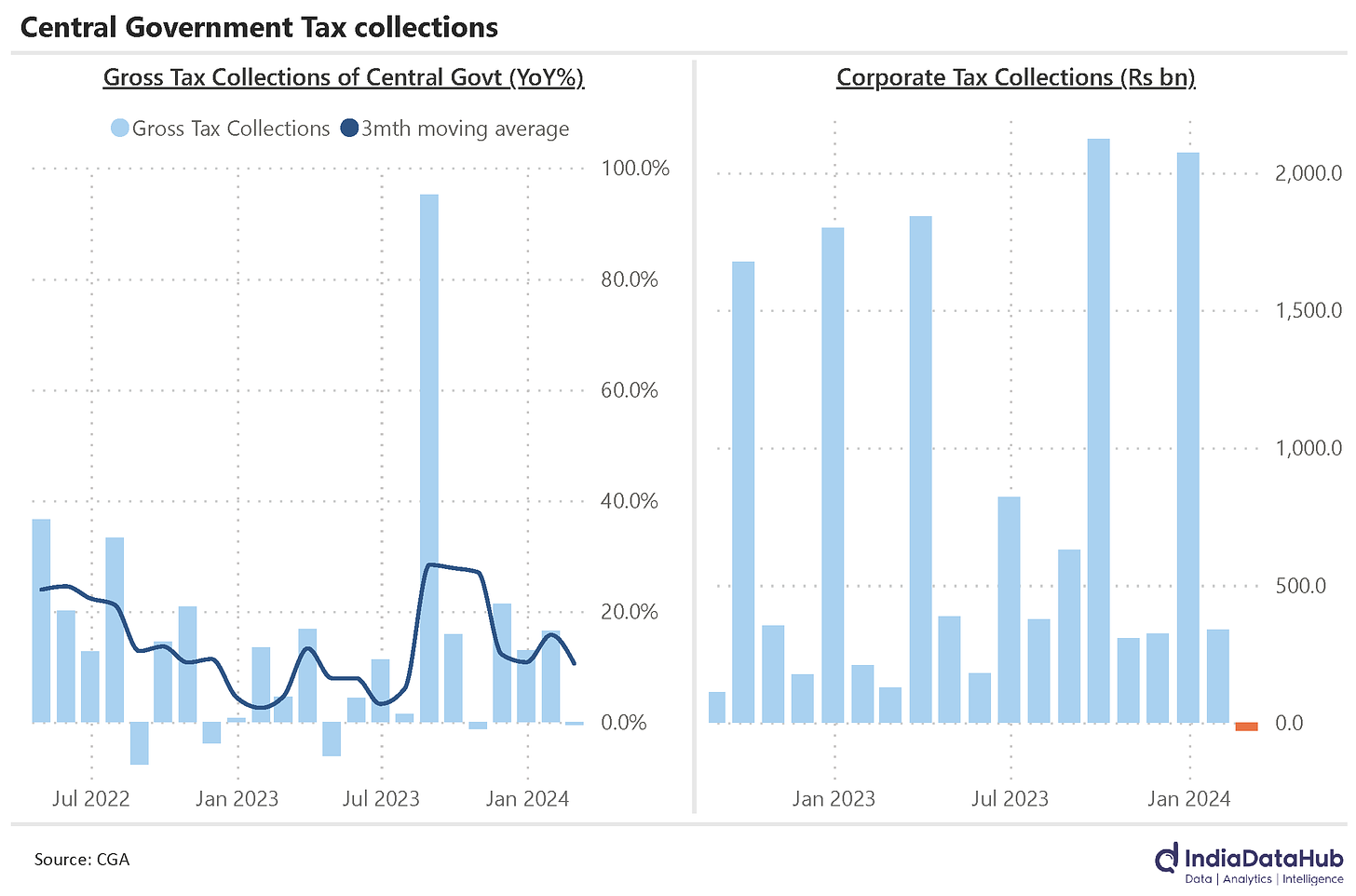

And finally: India’s tax collections have been unimpressive this February.

Mind you, the Government already expected a lull in its tax collections. One of the big surprises in February’s ‘interim budget’ (which we covered here) was how the government lowered its expectations of how much tax it could earn last financial year. But unless things have been far better in March than in February, it probably won’t even meet these lower expectations.

Oh. That’s a bummer. What’s happening?

The Central Government’s tax collections have been fallen this February, compared to February last year. To a great extent, this is because of ‘negative’ tax collections. In other words, the government paid tax to corporations.

That makes no sense!

Right. It shouldn’t.

The government was probably due to pay out several refunds on corporate tax, and it did so in a single bunch. As a result, it ended up paying out a lot of money in the space of just one month. So much, in fact, that the data shows negative corporate tax collections.

If you cut these out, however, tax collections grew by around 9% from February last year. That’s respectable, but still a little lower than the double-digit growth rate the preceding three months saw.

See this chart for more.

That’s all for the week, folks! Thanks for dropping by.