It’s the economy, stupid! Central banks take their bets

We love India Data Hub’s weekly newsletter, ‘This Week in Data’, which neatly wraps up all major macroeconomic data stories for the week. We love it so much, in fact, that we’ve taken it upon ourselves to create a simple, digestible version of their newsletter for those of you that don’t like econ-speak. Think of us as a cover band, reproducing their ideas in our own style. Attribute all insights, here, to India Data Hub. All mistakes, of course, are our own.

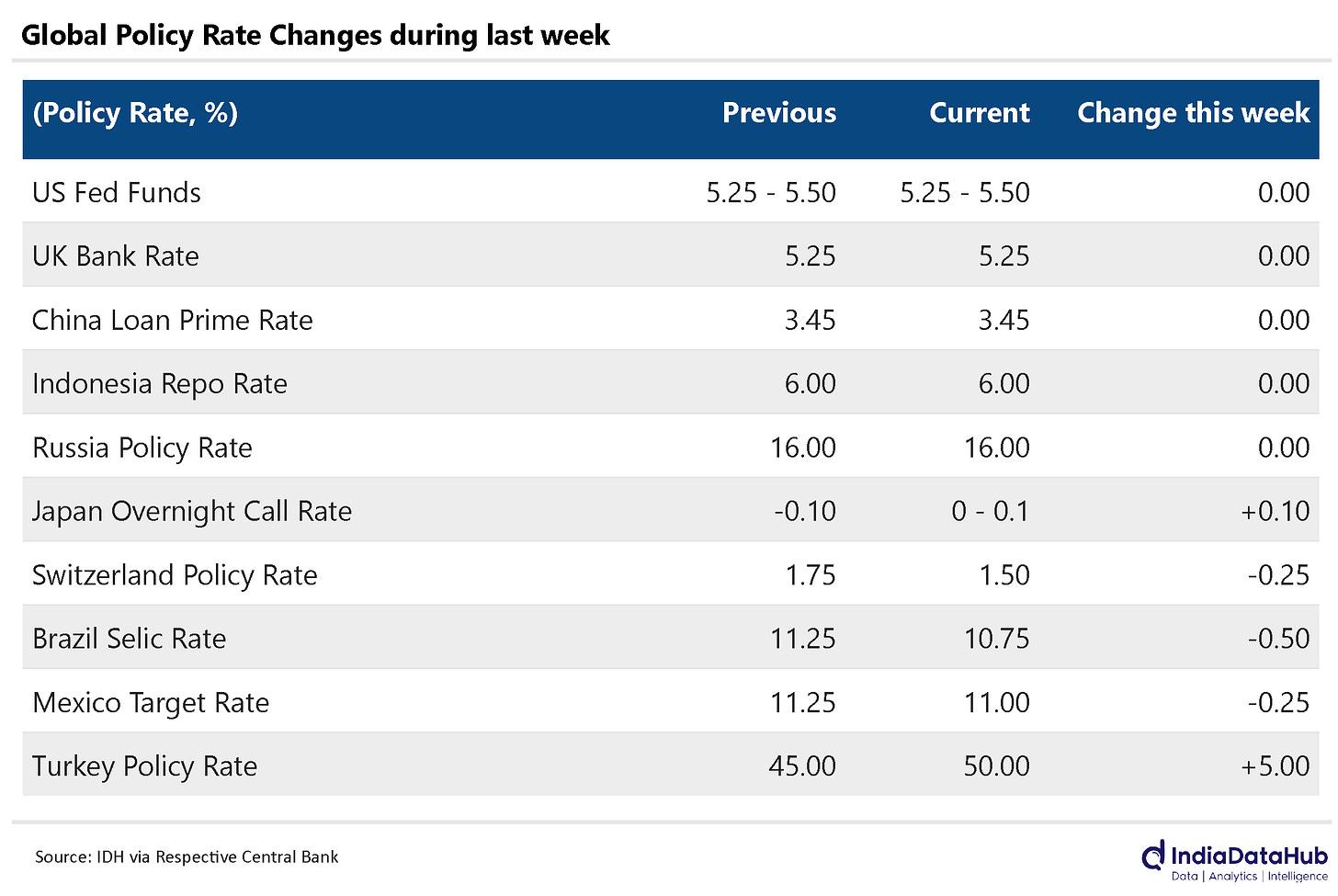

Last week, there was a blitz of central bank meetings from across the world. As many as ten central banks were in action through the week.

Look, I don’t care how you try to sell this. I refuse to get excited about meetings. On principle.

That’s… Well, that’s fair, I suppose. But there’s a deeper story here that might interest you.

While central bank meetings might seem sedate and boring from afar, think of what they’re really trying to do. Their job, simply, is to keep prices within a reasonable range. That’s been an exceptionally hard job in the last few years.

The global economy was never predictable, but at least it was stable before the COVID-19 pandemic. Most people ran on autopilot – with an established sense of how they did things and who they traded with. As the virus made its way across the world, however, everything briefly blinked out of existence. It never came back the same way. Its return was unruly and chaotic, with economies and firms abruptly exiting and re-entering global trade. The old ways of doing things had broken down. Everything grew expensive.

We’re still guiding things back to normalcy. This process hasn’t been easy: interrupted, as it has been, by open tensions and war between major economies, and by major trade routes getting choked. Prices are far from steady.

Central banks are reading the tea leaves in a situation where things can still turn on a dime, and then call the right policy for what may happen weeks from now. And that’s why we’re interested in them.

Sure. But what do central banks have to do with disease and war?

Directly? Nothing. But they have everything to do with prices. We spoke about this a few weeks ago, in fact:

“…money has value, and that value depends on what it can buy. Money loses value when there’s too much of it. If you add a lot of it to an economy without creating new things it can buy, soon, you need more money to buy each thing. It’s just simple demand and supply. This is why prices go up.

Fresh money enters an economy through bank loans. At least in theory, banks get this money on loan from the RBI, paying interest at a ‘policy repo rate’. Think of this as the price banks pay for any fresh money they loan. If the price is low, banks can give out a lot of cheap loans, and lots of money can enter the economy. If it is high, banks must charge much higher interest, and fewer people take loans. Less money gets into the economy.

There’s the rub. Loans, when used well, make an economy grow. At the same time, if too much money comes into an economy, prices go up. For an economy to run well, you must balance the two. And that is the job of the RBI: it must set the policy repo rate at a point that makes loans abundant enough for the economy to keep growing while keeping them expensive enough that money doesn’t flood the economy.”

Central banks across the world work in roughly the same way, setting the price of loans to give money a stable value. When goods become harder to buy, they make money harder to receive as well, so that some balance is maintained between the two.

Fiiiine. Tell me about these meetings.

Here’s a quick summary:

There were a few broad trends on display:

- Many countries – the United States, the United Kingdom, China, Indonesia and Russia – are biding their time. This does not mean inflation looks identical in these countries, simply that they’re all staying put where they were before. While the UK has left its rates at 5.25%, for instance, Russia is holding them at 16%. That is, Russian loans need to be thrice as expensive as British ones for their prices to come down.

- Some countries have bet that prices have come under control, and are bringing their rates down. Switzerland and Mexico cut rates by 0.25%, while Brazil slashed them by 0.5%.

- But there are two interesting stories of rates increasing:

- Japan had negative interest rates for eight years. Its economy has been limp for a while, and the country had cut rates down to a point where the Government was effectively penalising banks for not loaning out their money. This regime ended with last week’s meeting, when interest rates were raised to a range of 0-0.1%.

- On the other hand, Turkey’s inflation has been impossible to contain – trending well above 60%. That has prompted the Bank of Turkey to push rates up by an extra 5% – all the way up to 50%. There’s basically no point of taking a loan in Turkey unless you actually know how to double your money in a year.

So that’s how the rest of the world thinks. What about India?

I wish I knew. The honest truth is: the RBI may cut rates, or it may stay where it is for a bit longer. Nobody knows what it’ll do just yet. But we could try taking a guess:

- On one hand, its current, high rates have served their purpose. Inflation, as we’ve noted before, is coming under control. At the same time, money has been expensive for some time now, and economic activity is beginning to flag. The RBI will have to change gears at some point. And decisions on interest rates can take well over a year to actually have a real impact. Timely action is key.

- At the same time, there’s nothing compelling the RBI to suddenly change course. Economic activity, though not at its peak, is doing alright. The RBI has enough breathing room to prepare the markets for a change in rates before it actually pushes one through, and it will probably take that breathing room.

Chances are, the RBI will signal its intention to cut rates in its next meeting in April. Once the market readies itself, it will actually carry out those cuts in June.

The markets, it seems, are not expecting anything different.

How do markets, well, expect anything? How do we know what they are “thinking”?

In a nutshell, in the markets, people put their money where their mouth is.

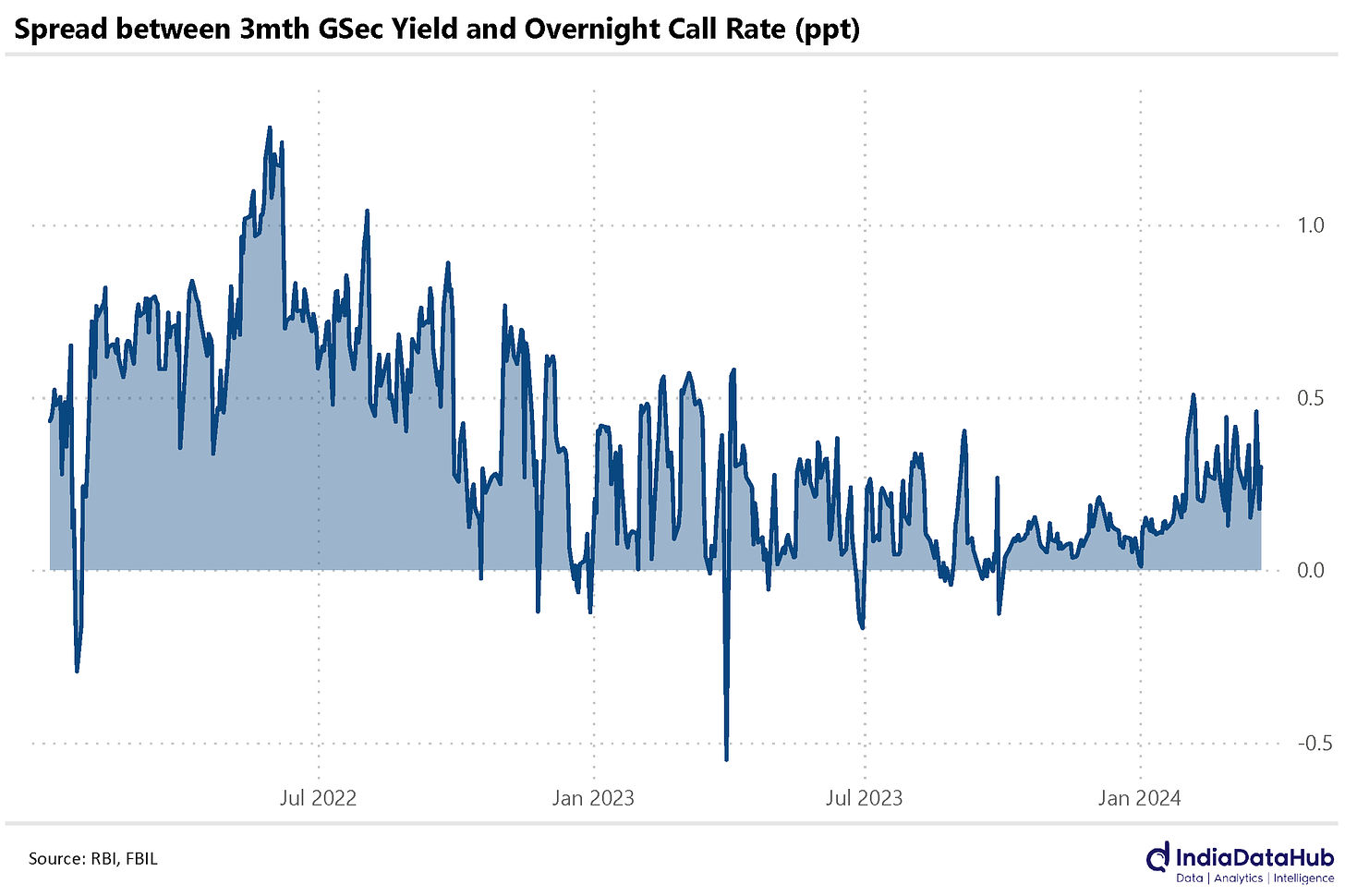

Currently, the yield on government securities is 0.3-0.4% higher than the ‘overnight call rate’. Let’s spend a moment with this impossibly terse sentence.

Banks usually let both sides of their business – deposits and loans – run in whichever direction they might through the day. At the end of each day, banks take stock of things. At this point, they might learn that they’ve run into problems. They might have lent out a lot more money than they have. They need to keep some minimum amount of money with them under the law, and they might not have enough. On the other hand, they may have excess money lying around that they have no use for.

So, at the end of each day, banks that have too much money give some out to those that have too little, for the space of just one night, until the chaos resumes on the next day. This is done over an ‘overnight market’. Banks charge a small interest for lending money on the overnight market. This interest – the ‘overnight call rate’ (which you can see here) – usually hovers somewhere around the RBI’s repo rate.

Now, both overnight lending and short-term government securities are considered extremely safe investments. Normally, you’re paid a similar interest for both. But a small gap – 0.3-0.4% – has opened out between the two right now.

This tells us that to someone in the market, it’s currently a lot more inconvenient to put money away for three months than for a single night. That’s why they want a better premium for it. This usually happens when money is in low supply, and there’s no real hope that there will be more of it soon. Like, for instance, when RBI interest rates are high, and nobody really believes that they’ll come down.

And that’s how we know what the markets are thinking.

We talked about ‘Foreign Direct Investment’ last month. This is what it means:

“You put in serious money for the long haul. You see a country as a good place to do business, and so, you roll up your sleeves and dive in. You buy up a big piece of a company, or if you’re very brave, you start a business from scratch, and then get involved in running it. This is ‘foreign direct investment’ (FDI).“

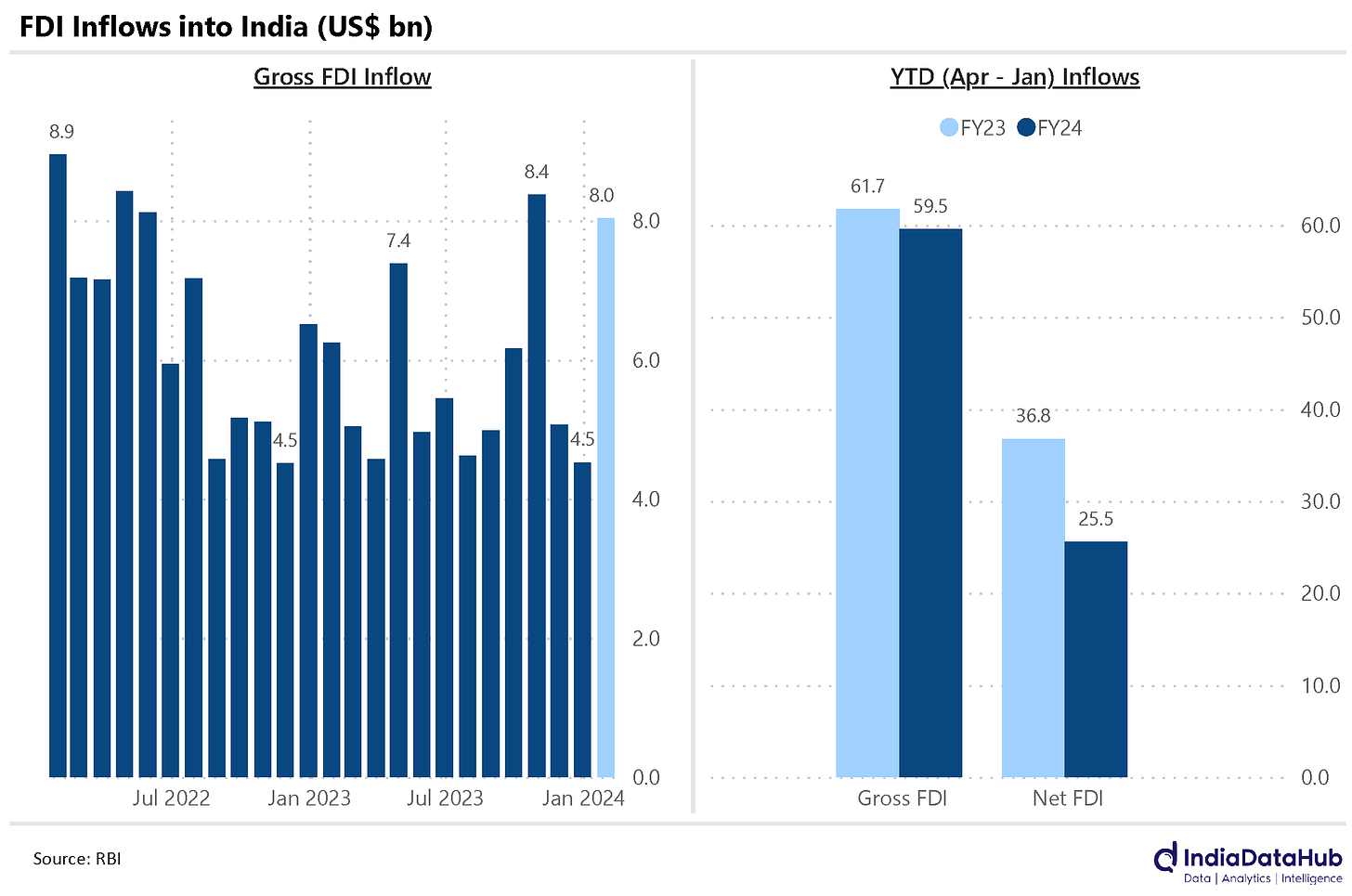

Last time around, we were worried that money was leaving the country in December.

Yes! All the investors were running away!

Hehe. Nothing that dramatic. But yes, we saw two things happen at the same time: fresh investment was particularly low, while more money was going out than before. Taken together, in December, more money left the country than what entered it – for the first time ever.

Has anything changed since?

Oh yes! January saw massive inflows of FDI. In total, US$ 8 billion entered the country in the month, more than compensating for December’s poor showing.

That said, we had spotted a wider trend last week, which persisted in January. As we said last week:

“There’s a trend you should think about, though: a lot of FDI has generally been leaving the country.

In 2019, an average of US$ 1.7 billion in FDI was exiting India every month. In 2023, that’s jumped up to US$ 3 billion. Although December saw a massive spike in outflows, even in the long term, FDI is leaving India at a faster rate.”

This holds true even now. In absolute terms, the amount of FDI that we received this financial year (i.e. from April 2023 to March 2024) will probably be marginally lower than we did in the preceding year. If you account for how much money left India through the year, however, our ‘net’ FDI is a full 30% lower than last year.

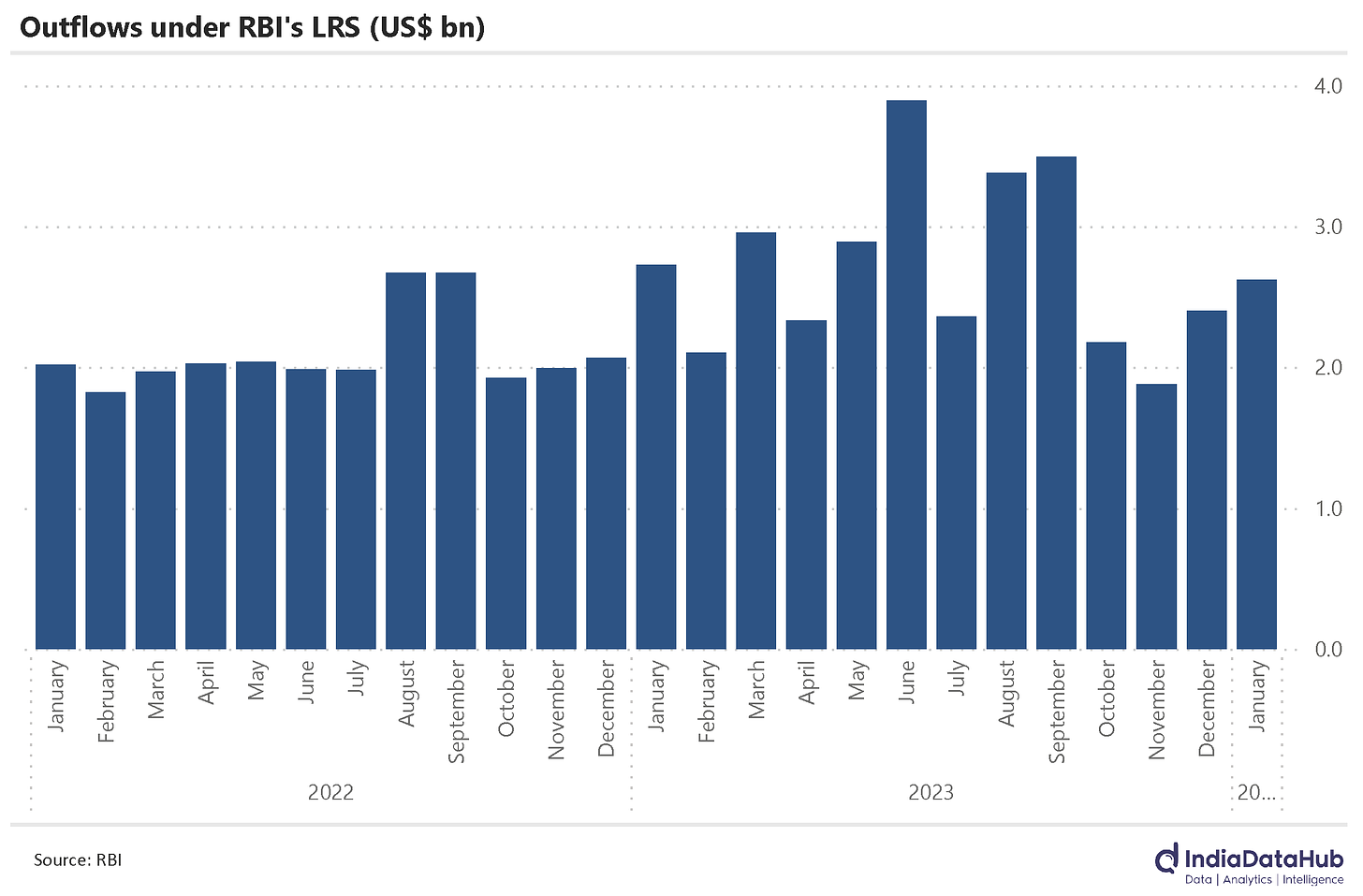

Do you remember how we talked about LRS outflows last month?

Do you remember what pants you wore on a Monday eight weeks ago?

No, but that’s barely important to my-

And your point is?

Gah. So ungrateful. Here’s a recap, though:

“The RBI doesn’t want the Rupee to lose value, because that makes it harder for us to buy the things we really need. This is why it limits how many Rupees an Indian resident can spend abroad. It’s put together a ‘Liberalised Remittance Scheme,’ (LRS) which allows you to send out Rupees worth US$ 2.5 lakh in a year without running into hassles. Need to send more? Well, now you have to fill forms and deal with bureaucratic hurdles, which makes the whole thing a lot more painful.

That’s not all. When you send out any more than ₹ 7 lakh under the LRS, your bank cuts some of it as ‘Tax Collected at Source’ (TCS). That’s counted as part of your income tax payment for the year. This cut used to be 5%, but with last year’s budget, it’s jumped up to 20%.

So it’s become rather difficult for ordinary people to send Rupees abroad. And yet, they’re doing so more than ever.”

Oh right. People were spending tons of money abroad. Is that still happening?

Quite so. January, in fact, saw a four-month high in the money that left the country – at US$ 2.6 billion. Our outflows were only slightly larger in January last year, and that before anybody had to pay a TCS.

That’s all for this week, folks. Thanks for reading!

Hi Pranav. Your articles are really insightful. Is any option there to download in pdf format?

Thank you so much, Sridhar! We don’t have a separate option to download our articles in PDF, but you may consider printing it as a PDF from your browser if you’re accessing this using a laptop / desktop.