It’s the economy, stupid: Monetary policy, China and more

We love India Data Hub’s weekly newsletter, ‘This Week in Data’, which neatly wraps up all major macroeconomic data stories for the week. We love it so much, in fact, that we’ve taken it upon ourselves to create a simple, digestible version of their newsletter for those of you that don’t like econ-speak. Think of us as a cover band, reproducing their ideas in our own style. Attribute all insights, here, to India Data Hub. All mistakes, of course, are our own.

Last week, the RBI’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) took a decision on interest rates: it would do nothing. Just as people thought.

So.. what is it supposed to do? Should it have done something?

Well, it’s complicated.

It’s the RBI’s job to keep inflation – or price rises – in check. But prices are set by millions of factory owners, office managers and shopkeepers. How can a central bank control what they all do?

Before we get to the answer, imagine: what would happen if you woke up one day and everyone had a hundred times as much money as before? Would you be able to buy things at the same price? Would you be able to pay a worker the same? Or an auto driver? Maybe you would for a bit, during a brief period of adjustment. But eventually, people would realise that everyone had much, much more to spare. They would keep running prices up until they’d hit a limit of what people could pay. They’d refuse to accept the old prices; after all, why would they put all that work in for a mere fraction of the money they suddenly had? Over time, things would begin to look quite like they did before, except that everything would be a hundred times as expensive.

See, money has value, and that value depends on what it can buy. Money loses value when there’s too much of it. If you add a lot of it to an economy without creating new things it can buy, soon, you need more money to buy each thing. It’s just simple demand and supply. This is why prices go up.

Fresh money enters an economy through bank loans. At least in theory, banks get this money on loan from the RBI, paying interest at a ‘policy repo rate’. Think of this as the price banks pay for any fresh money they loan. If the price is low, banks can give out a lot of cheap loans, and lots of money can enter the economy. If it is high, banks must charge much higher interest, and fewer people take loans. Less money gets into the economy.

There’s the rub. Loans, when used well, make an economy grow. At the same time, if too much money comes into an economy, prices go up. For an economy to run well, you must balance the two. And that is the job of the RBI: it must set the policy repo rate at a point that makes loans abundant enough for the economy to keep growing while keeping them expensive enough that money doesn’t flood the economy.

Oh. So how do things stand today?

Here’s what happened at the MPC meeting:

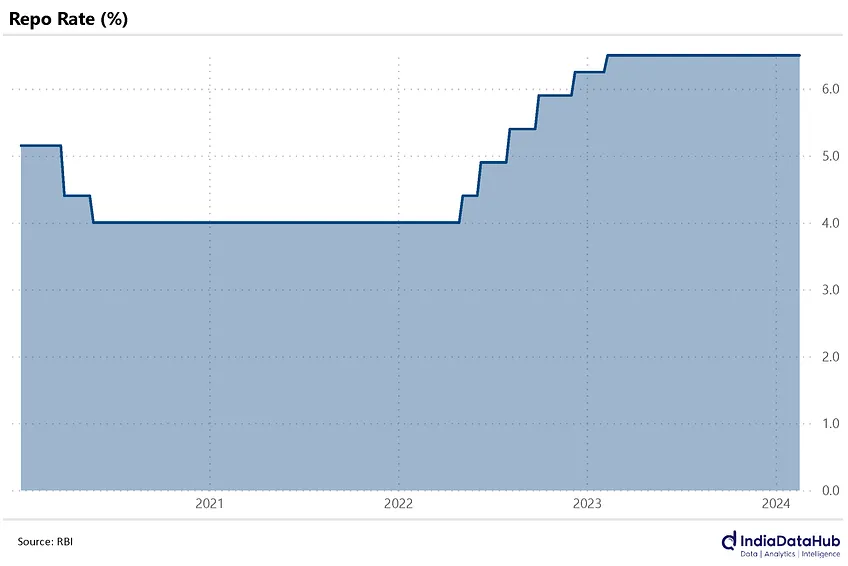

- The RBI kept its policy repo rate at 6.5%. It’s been there for a year, ever since it jumped from 6.25% to 6.5% back in February 2023. The chart below maps its path through the last few years.

- The decision wasn’t unanimous. One of the MPC’s members, Professor JR Varma, wanted rates to drop to 6.25%.

To the markets, however, the RBI’s decision was hardly a surprise. See, bond markets try and predict what the RBI does in advance. The value of investors’ money depends on how much money there is in the economy. In the days before the meeting, if most people believed that a rate cut would draw more money into the economy in the short term, they would be reluctant to make short-term investments themselves. If the RBI doing nothing was a surprise, you’d see a sudden flurry of activity in the market immediately after its announcement. This time around, though, the bond market barely sneezed.

Whoa! That looks high! So it just stays there now?

Uhh.. That’s a tough one to answer.

The markets believe that the MPC will bring down rates soon. Most professional forecasters see rates coming down to 6.25% by June. This might just be wishful thinking, though. Here’s what we know:

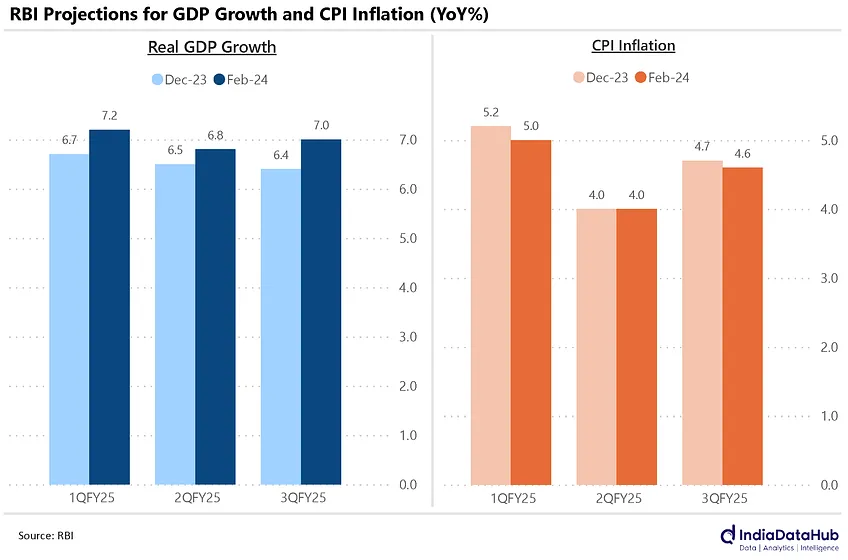

- Growth seems healthy for now. The RBI thinks the Indian GDP will grow at 7% in the next financial year: the same rate as it did this year.

- At the same time, inflation has been rather stubborn. The RBI believes that in FY 2025, on average, prices will be 4.5% higher than they are this year. This isn’t terrible – it’s certainly better than this year’s 5.4% – but it’s still above RBI’s target of 4%.

Let’s get back to the balance RBI is supposed to strike. It needs to make money cheap enough that the economy grows, and expensive enough that inflation is limited. Now, on one hand, the economy is chugging along rather well. On the other hand, there’s a smidge too much money in the economy, which is still sending prices up high. At the moment, there’s no tearing hurry to bring interest rates down.

Moreover, the US Fed (America’s RBI) will probably keep rates high as well.

Eh, whatever. Why do I care about the US?

Ah, but the US Fed rate is very relevant to us.

American money funds the world. Extra dollars from the US reach all other markets, India included. When this tap runs dry, economies across the world have less money coming in.

Now, when someone invests a dollar in India, in essence, they buy rupees in exchange for the dollar they spend. The more people want to invest in India, the more valuable the Rupee becomes. When they don’t, the Rupee loses value.

But, but, but: India pays in dollars for most things it imports. With a less valuable Rupee, it must pay more dollars for anything it buys. Things become more expensive. That is, there is inflation in India.

Simply put, when the US Fed stymies the availability of dollars, it’s harder for the RBI to fight inflation in India.

Fiiiine. Tell me what’s happening in the US.

There’s a chance they might do nothing.

Like the RBI, over the last couple of years, the US Fed has been trying hard to fight inflation. It has pegged rates in the range of 5.25-5.50% since July last year: the highest they have been in the last two decades. But US inflation has been looking better lately. People were willing to bet that rates would come down soon. A month ago, markets thought there was a 90% chance of a cut by May. They’ve tempered their expectations since. Now, they’re only giving it a 60% shot.

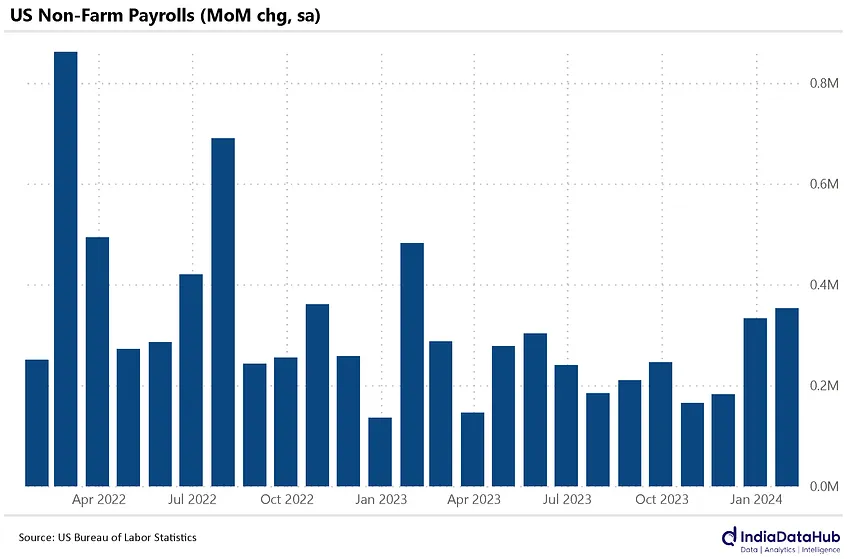

As in India, the US economy has been growing well despite high rates. Its job markets, in particular, have been fantastic. This January, for instance, the US posted its highest job growth in a year: adding 350k jobs – almost twice as many as people expected. Once again, there’s no tearing hurry to bring rates down.

That’s that for inflation. But the RBI has also put out the results of a few recent surveys.

Surveys, huh? I’m already asleep.

Have it your way. But there’s a pretty interesting story they tell about India’s economy.

Ugh.

I’ll make it quick.

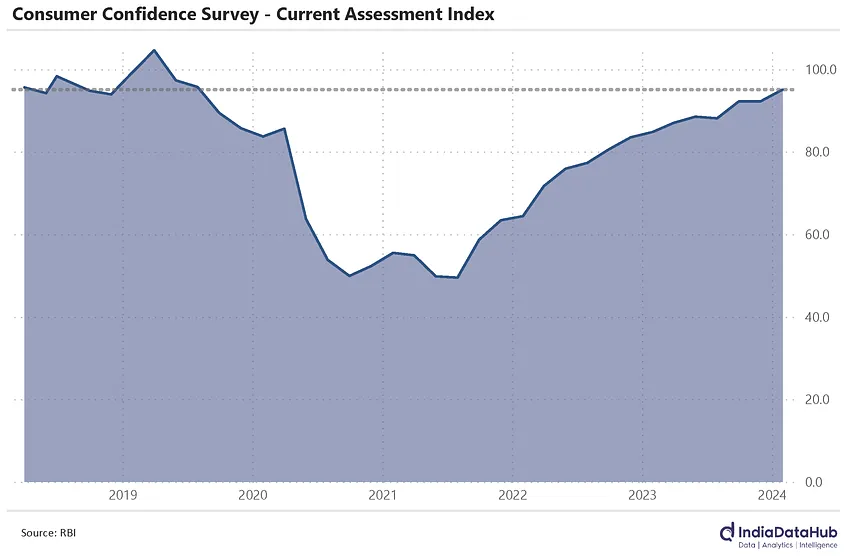

The survey – called the ‘Consumer Confidence Survey’ – tells you about how good consumers (in 19 big cities, that is) think the economy currently is, and how good it will be. As the chart below tells you, people seem optimistic. In fact, things haven’t looked this good since July 2019.

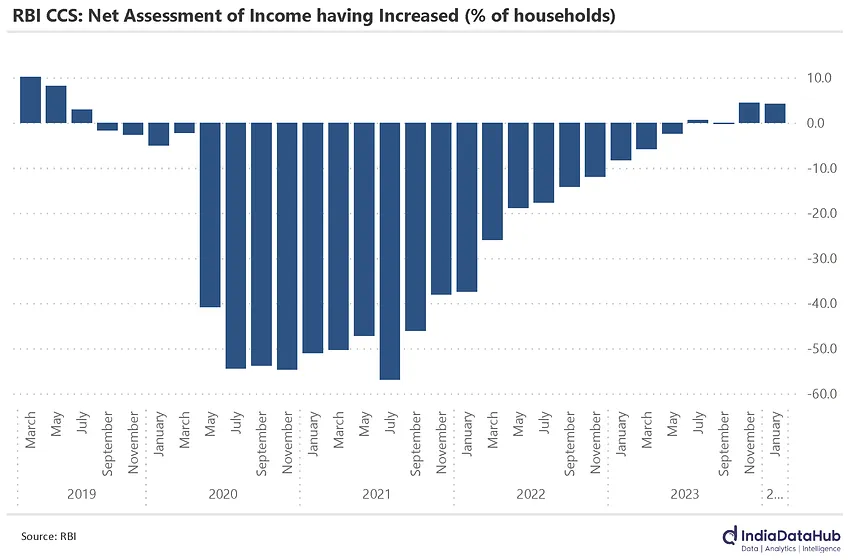

What’s more, people think they’re earning more than they did last year. Around 26% of those polled thought they were better off, outnumbering the ~22% of those who thought they were worse off – a margin of 4%. Things last looked this good almost four years ago – back in May 2019.

So things are really great, huh?

Welllll. There’s a catch.

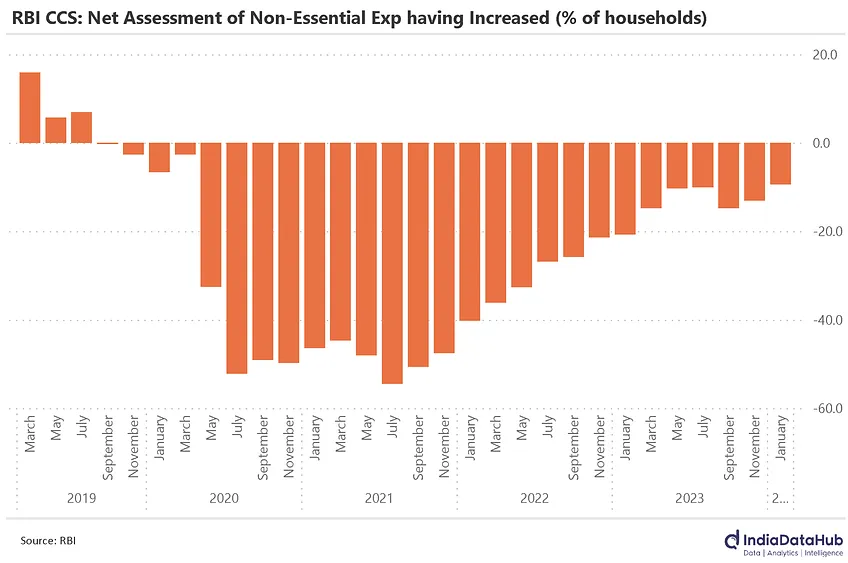

People aren’t spending on things they don’t absolutely need. Almost 37% of people think their non-essential expenses declined over the last year, while only 27% increased non-essential spending – a difference of 10%. For whatever reason, even when people think they’ve been earning more, they’re holding off on spending money.

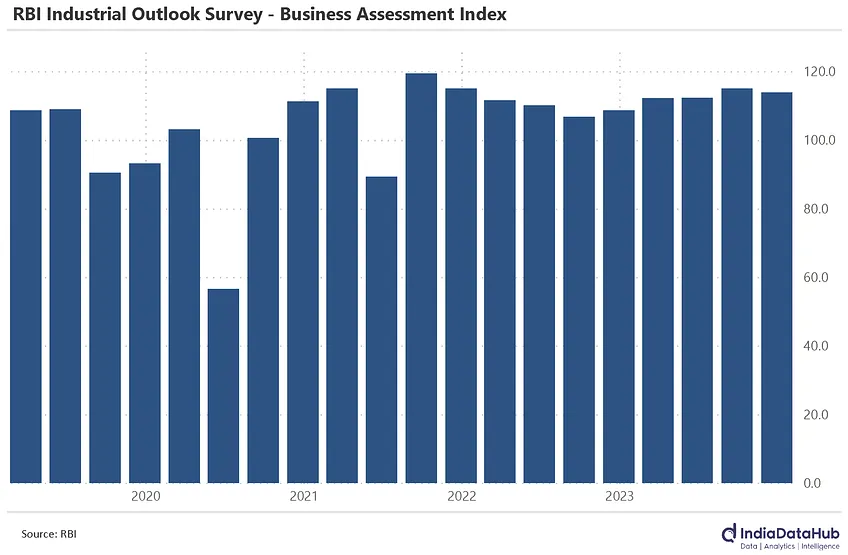

In contrast, manufacturers are extremely happy. The RBI also released the results of its Industrial Outlook survey – which looks at how manufacturers feel about their orders, finances, profits, and more. And things look fantastic – better than they were before the pandemic.

In all, while things look complicated for consumers – they’re holding off on spending despite earning a little more than before – manufacturers are doing better than ever.

Why’s that? Ah, that’s the puzzle.

China, meanwhile, is not doing all too well.

Hmm. Why?

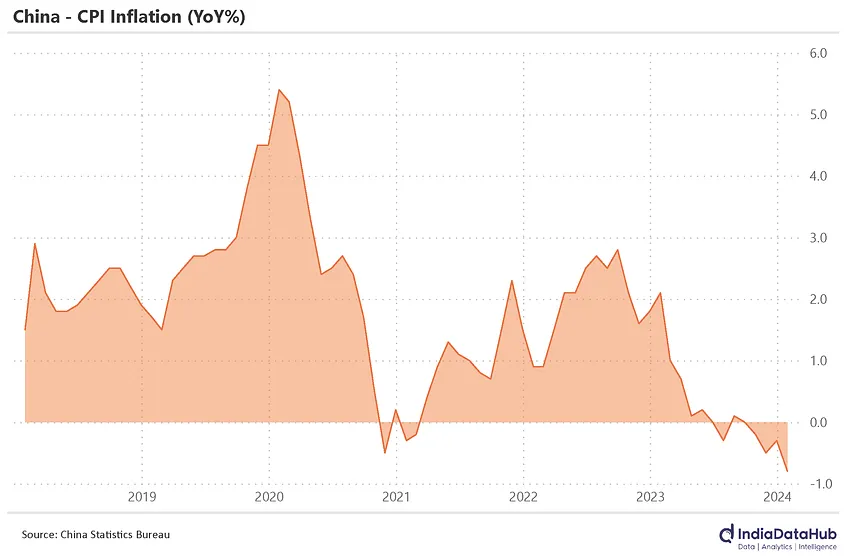

Inflation in China has been deeply negative. That is, the country is seeing deflation. Prices are falling across the board. Some highlights:

- This January, prices were 0.8% lower than the last: the biggest drop in fifteen years. This is the fourth straight month of deflation China has seen.

- Food was 5.4% cheaper than last year, on the back of a decline in prices of pork and transport.

- For everything else, prices fell by 0.4%.

Here’s how prices have behaved over the last few years:

I think you mean China has been doing great. What’s not to love?

Think a little harder. Why would everyone willingly cut prices? Across an entire economy?

That happens when people refuse to spend money like they once did. There are, then, too many things in the economy that nobody wants to buy. It’s a sign that the economy is less vibrant than it once was. And it throws everyone in a tizzy.

Businesses, in order to survive the bad times, must drop prices. But that isn’t easy. You might have to scale things down, and perhaps fire workers. People hold off on investing in the future because as things stand, they look to make less money going ahead. Paying loans off becomes difficult when your profits take a beating, so people stop borrowing. Money stops entering the economy. Over time, economic activity winds down further.

That can make things worse. With fewer jobs and less investment, people are even more reluctant to spend. In a worst case scenario, the economy starts to spiral downwards, and you have a crisis on your hands.

That’s where China is today. Anything could happen. Watch this space keenly.

That’s all for the week, folks. Thanks for reading.