15.1 – Building blocks

Picking up from the previous chapter, we discussed relative and absolute valuation concepts. At its core, three key inputs drive the absolute valuations –

-

- The cashflow

- The timing of the cashflow

- The rate at which the cash flow gets discounted

Let us deal with the broader concept of cash flow in this chapter. Remember, starting from the previous chapter to maybe the next few, we only discuss the theory behind the valuation. Once we get to a stage where we understand the valuation concept well, we will build the valuation model and integrate it within the model we have built so far.

The cash flow that we refer to here is called the ‘Free Cashflow.’ Free here implies that the company is free to allocate the cash generated from its operations to whatever purposes the company thinks is best—extending the thought, who owns that cash that the company’s operations generate? To answer that, you need to think about the company from its funder’s perspective. A company gets funds from two sources, i.e., debt and equity.

The debt and equity holders together finance the assets of the company. Hence, the following equation represents a company –

Debt Holders + Equity holders = Assets of the company

In its simplest form, the debt and the equity holders finance assets, the assets, in turn, generate a cash flow for the company. So the cash generated by the company belongs to both these funders in proportion to their funding. Further, we value the cash flow by factoring in the cash flow timing and the discount rate to develop our sense of the company’s valuation.

In its simplest form, the debt and the equity holders finance assets, the assets, in turn, generate a cash flow for the company. So the cash generated by the company belongs to both these funders in proportion to their funding. Further, we value the cash flow by factoring in the cash flow timing and the discount rate to develop our sense of the company’s valuation.

The point to note here is that the cash generated belongs to the company, i.e., the Debt + Equity funders. The cash that belongs to the company is called ‘The free cash flow to the firm’ (FCFF). Or, from the free cash flow to the firm, you can deduct whatever cash is supposed to go to the debt holders and value only the cash flow that belongs to the equity holders, and that is called the ‘Free cash flow to Equity (FCFE).

15.2 – Free cash flow calculation

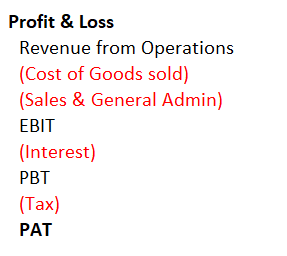

To calculate the free cash flow (FCFE or FCFE), we need to start all over from the P&L again. Don’t worry, I won’t do a P&L deep dive but rather quickly discuss the overview. It may perhaps help you jog your memory. Have a look at this –

The company’s business operations ideally should generate positive cash, which is also the company’s revenue. The company pays off the cost of goods sold from the revenue generated. After paying for the cost of goods sold, the company pays the sales and general administrative costs. Usually, both get clubbed as the ‘expenses’ of the company. After adjusting for this, the company is left with ‘Earning before the interest and Tax’ or the EBIT. EBIT is one of the key margin metrics we use to analyze a company.

The company’s business operations ideally should generate positive cash, which is also the company’s revenue. The company pays off the cost of goods sold from the revenue generated. After paying for the cost of goods sold, the company pays the sales and general administrative costs. Usually, both get clubbed as the ‘expenses’ of the company. After adjusting for this, the company is left with ‘Earning before the interest and Tax’ or the EBIT. EBIT is one of the key margin metrics we use to analyze a company.

From EBIT, interest is paid to get us to the Profit before tax or PBT. From PBT, the company pays the taxes due for the financial year and finally arrives at the company’s bottom line, i.e., Profit after taxes or PAT.

All the above is very intuitive, I guess. The point to note here is the source of free cash, irrespective of whether you look at it from the firm’s perspective or equity holder’s perspective starts with the company’s operations after adjusting for expenses and taxes. This implies that we can start figuring out the true ‘Free cash flow’ by starting with the company’s bottom line, i.e., the Profit after taxes (PAT). What do I mean by ‘true’ free cash flow? I’m talking about identifying all the non-cash expense and adding it back to the PAT to figure out the free cash flow.

The cost of goods sold part usually includes depreciation as well. Remember that depreciation is just an allocation of charge, and it is not an actual expense. It is an accounting entry. Likewise, amortization is also a non-cash expense; it is an accounting entry. The first step in calculating the free cash flow (irrespective of FCFE or FCFF) is to add back depreciation and amortization to PAT.

Think about deferred taxes; this too is not an actual expense, but instead, the company is deferring its tax payment to a later date. Given this, you can add back deferred taxes as well.

So we have –

PAT + Depreciation + Amortization + Deferred Taxes

Please think of the above equation as the starting cash position. We now have to account for changes in the company that consumes cash. The changes I’m referring to are working capital changes and changes in the fixed assets position of the company.

To keep the operations going, the company should spend on working capital. As you may know, working capital is the funds required to run the day-to-day operations of a company. Day-to-day operations like picking up raw material on credit by a vendor, receiving an advance from the customer, stocking inventory, etc., are all activities that come under the company’s working capital. The balance sheet equation of working capital is –

Working capital = Current Assets – Current Liabilities

Note, since both assets and liabilities are current, working capital is also current.

Assume the average working capital requirement of a company is 100Crs, but for whatever reason, the working capital requirement increases to 120Cr, then the additional 20Crs will have to be accounted for when calculating the free cash flow. It is reduced from PAT + depreciation + amortization + Deferred Taxes.

Likewise, if the working capital decreases to 80Crs, it frees up 20Cr for the company, added back to the free cash flow calculation.

Next up are the fixed assets of the company. The company must invest in fixed assets. The general opinion is that these fixed assets will help the company generate higher operating cash in the future. Usually, the company’s fixed assets spend is predictable, but just like the working capital changes, the changes in fixed assets should also get factored in.

Considering both the above, our free cash flow equation looks like this –

PAT + Depreciation + Amortization + Deferred Taxes – Change in working capital – change in fixed asset investments.

Now, here is an interesting bit. If you relook at this again –

When we start free cash flow calculation, we start with the PAT of the company. But before we arrive at PAT, we payout interest or the finance charges. Now, think about it, to whom does the interest payout belong to? It goes to the debt holders, which means that if you were to look at the free cash flow to the firm, then we also need to add back the interest to our free cash flow calculation. Hence, the equation now looks like this –

PAT + Depreciation + Amortization + Deferred Taxes + Interest charges – Change in working capital – change in fixed asset investments.

The above equation is the free cash flow to the firm or the FCFF. Now, from the free cash flow to the firm, if you separate the cashflow which portion belongs to the debt holders and that will leave you with the part that belongs to the equity holders, which can then get valued and get a sense of company’s valuation from the equity holder’s perspective.

Think about what the debt holders expect from the company? Unlike the equity folks, debt folks have a different payout expectation. The debt funders lend a certain amount (principal) to the company and expect the company to pay interest against the principal amount. At the end of the tenure, the debt holders expect the principal to be repaid in full. So from the free cash flow equation that we arrived at earlier, if we separate the principal repayment and the interest payments, we are left with the ‘Free cash flow to the Equity.’

I hope the above explanation is clear about arriving at both FCFF and FCFE. We will get into a more detailed description in the next chapter, especially when we implement the absolute valuation model within the financial model we are building. But for now, I intend to give you an overview of how various elements of valuation come together.

15.3 – Return expectations

We now have a broad overview of how to calculate the free cash flow to the firm and the free cash flow to equity holders. Let’s quickly understand the return expectation from the firm and equity holder’s perspective.

To get a sense of the return expectation of the firm, we should be clear about what the debt holders expect. The debt holders of the firm, as we discussed earlier, expect an interest payment against the principal amount, plus at the end of the tenure, they expect the principal itself to be repaid.

The firm has to satisfy the debt holders’ return expectations. But the firm also has equity holders, who will have a different return expectations. So when you are thinking about the firm’s free cash flow, then because the firm has both debt and equity holders, the return expectation of the firm should be such that it satisfies both debt and equity holders. If you build a valuation model based on FCFE, the cash flow is discounted with a blended rate, satisfying both the debt and equity holders.

Let me give you an example. Assume a company has 350Cr, of which debt is 125Crs, and the equity holders fund the balance 225Cr. The debt holders expect a 9% return, and the equity holders expect a 15% return. Why they expect what they expect is something we will discuss later. However, from the company’s point of view, it should generate a blended return to satisfy both, i.e., the expectation of the firm is the weighted average return –

= (9%*125) + (15%*225) / 325

=13.85%

The blended rate of return is also called the ‘Weighted cost of capital (WACC). We will discuss this later.

Think about the equity holder’s return expectation. The equity holders will expect a higher return than the debt holders because the equity holders take more risk. Equity holders expect at least the risk-free rate that prevails in the economy plus a risk premium for the additional risk (over the debt holders) that they take. The return expectation of equity holders is called, ‘The cost of capital’.

Cost of capital = Risk-free rate + Risk premium

Note that the cost of capital is always higher than the WACC. In this chapter, I’ve laid down the basic foundation for the FCFF and FCFE and touched upon the return expectation. In the next chapter, let us try and take a closer at the same.

Key takeaways from this chapter

-

- A firm can be looked at as a combination of debt and equity holders

- The debt and equity holders finance the assets of the company

- To get the FCFF, we start with PAT and add back all non-cash expenses

- From FCFF, we deduct interest and principal repayments to get FCFE

- The weighted cost of capital is a blended rate, and it is the expectation of the firm

- Cost of capital is what return expectation of the Equity holders

- The cost of capital is always higher compared to WACC

Can you explain why interest *(1-t), as in tax benefit is added back to net income when calculating FCFF?

The tax outflow reduced when you have an interest component, this is called the tax shield.

What is the difference between Cost of capital and WACC?

Cost of capital is usually for a single funding source for either Debt or EQ investment, but WACC is a blended cost involving both EQ and Debt in respective proportion.

\”If you build a valuation model based on FCFE, the cash flow is discounted with a blended rate, satisfying both the debt and equity holders.\”

Shouldn\’t this be FCFF, because because FCFF will include the debt component, so it would make more sense to apply the blended rate to FCFF right?

FCFE includes WACC, which is a blended rate, right?

Supposingly I am taking the whole project life so the effective debt is 0. For eg: suppose year 1, I am taking 20 Cr debt and in next 4 years I am repaying 5 Cr each year so in a project life of 10 years, my net borrowing is net 0. So effectively my FCFE = FCFF + tax shield (because this I saved for myself as I took the loan)

But this wont give you the accurate enterprise value, Sourabh. I\’d suggest you factor in debt.

Hi I checked various sites, some say that FCFE = FCFF + Int(1-T) – Net borrowings.

Now tell me one thing over the complete life of a project , the net borrowing is to be 0 right, because you are repaying all the debt, so wont it make sense deducting only the principal component because the interest component of a debt is already deducted while computing FCFF?

Not necessary right? Debt can be repaid over the years.

if a firm has debt, it has to pay interest but it gets tax shield effect

Then why nithin sir did not take debt, just a thought

Well,there should be a reason to take debt 🙂

Hi Karthik, ty for putting out such good resource, i am stuck on a small ques, kindly share our views on it, why do we add the interest to our free cashflow. we are giving out money, its less cash now. ty 🙂

Shekhar, when companies pay out interest there is a tax shield effect, which means that the companies pay out lesser taxes. So interest is added to capture this effect.

Learning with joy!Thanks.

Glad, happy learning 🙂

Sir. This explanation is very clear on your module itself when I read. In fact I have also read Mr.Aswath Damodar\’s book to understand this.

So no confusion on the difference between FCFF AND FCFE.

What I don\’t get is when we say FCF = CFO – CAPEX, which FCF are we referring to here? Are we referring to FCFF or FCFE?

Thanks.

(I\’m really hesitant to post follow up questions sir. I really don\’t want to disturb you. I know you have already answered many, but the more I read more questions pops up and sometimes I don\’t get the meaning. No person that I can ask to either.)

Hey Sathish, dont hesitate to ask. I\’ll certainly answer if I know the answer, else I\’ll say I dont know 🙂

FCF here refers to the free cashflow to the firm here.

I have read this module sir. Got Stuck in between, gave like 2 to 3 times try before finishing it. I will give it another read.

But what I meant was that in Fundamental analysis module DCF chapter, you have mentioned to give a discount rate of around 15% for small caps. But if I use WACC, sometimes that 1-2% reduction in discount rate gives better values. That is why I asked whether I can use WACC instead of using a round number like 15% in case of small caps.

I do understand the difference between FCFF and FCFE. But I don\’t understand which type is the better one to use for valuation purpose. Like when you say CFO – Capex, it sounds so simple but when you expand the formula like,

(FCFF = PAT + Depreciation + Amortization + Deferred Taxes + Interest charges – Change in working capital – change in fixed asset investments) it sound complex.

So I don\’t want to assume but confirm whether normal FCF calculation(CFO – Capex) and FCFF are the same or somewhat different. I had this doubt for a long time. So if you could answer this in a simple way it would be helpful.

Thanks

1) FCFF = Free cash flow to firm

2) FCFE = Free cash flow to Equity holder

Both are different, Sathish. The first one is valuation based on the free cash flow available to the entire compnay i.e Equity plus Debt holders, and the 2nd one is free cash flow to only equity holders.

Yes, the formulas can get a bit complex, but there is not much we can do about it 🙂

You can use, WACC.

1. In the fundamental analysis module, where you have described about DCF, in that can I use the weighted average cost of capital as the discount rate for DCF analysis?

2. When we are calculating FCF from cash flow statement, that is, CFO-capex, we are calculating the free cash flow to firm (FCFF)right?

Have discussed all this and more here – https://zerodha.com/varsity/module/financial-modelling/

1) When I am valuing the the company from the firm\’s perspective,i.e FCFF isn\’t doing the valuation on FCFE would go hand in hand? As ultimately after valuation I would invest in as a shareholder only,so valuation through FCFF is to get an overall idea as to how the firm as a whole will do the business as FCFE would thereby depended on the same.

2) Also when I am valuing through FCFF,should I look it from Third person perspective (TPP) or should I consider myself as the business entity.Just to get a clear picture.

Guide for thew same.

Thanks in Advance.

1) Yes, after all FCFE is FCFF – the debt component

2) Basically this is an outside view, so maybe 3rd person 🙂

Sir actually today I took your varsity basics stock market certification I completed it but there was a question where there is wrong answer ticked

As we have to buy shares before ex dividend date to be eligible for dividend but there it is written before record date kindly check

Ah, ok. Thanks for pointing that out, Vivek.

Good day Karthik,

You and the folks at Zerodha are doing a wonderful job and have personally impacted me a lot in my journey through financial literacy. I had a few questions which are as follows:

1. Why can\’t one use just the Cash from operations + Trade receivables as the FCFE perspective and for DCF analysis?

2. In the \”weighted average return\” example, the denominator should be 350 right adding the two weighages of 125 and 225?

Keep up the amazing work!

1) Trade receivables is a sort of provision and not actual cash on hand right?

2) Oh yes, that\’s a typo 🙂

Hello Sir, when will we able to download the soft copies of Mind over Markets and Financial Modelling?

We won\’t put up the PDF of mind over markets. FM, once it is complete.

can you please tell us at what is final date at which you can upload the complete course ?

I don\’t have a date as such, Parth. But it is my intention to finish as early as possible.

I want to learn about financial modeling through your blog so,

Can you please tell how many chapter is left to complete financial modeling course ?

Parth, another 3-to 4 chapters I guess.