It’s the economy, stupid! Food, Roads, Jobs and the Internet

We love India Data Hub’s weekly newsletter, ‘This Week in Data’, which neatly wraps up all major macro data stories for the week. We love it so much, in fact, that we’ve taken it upon ourselves to create a simple, digestible version of their newsletter for those of you that don’t like econ-speak. Think of us as a cover band, reproducing their ideas in our own style. Attribute all insights, here, to India Data Hub. All mistakes, of course, are our own.

Wheatish complication

The harvest is in! And if you’re the sort of city slicker that isn’t sure why this matters to you, well, I have a story to tell.

This is India’s spring harvest – the harvest of rabi crops. And the most important rabi crop is wheat. Wheat is so crucial, in fact, that the government stores millions of tonnes of it in granaries across the country. It can stay there for long: years at a time, even. If there’s ever a bad harvest, if we ever grow less food than we need to feed ourselves, we rely on this stored grain.

At the moment, though, India’s wheat stocks are the lowest they’ve ever been in more than fifteen years, at a mere 7.5 million tonnes. This graph will tell you just how low that is:

India also runs the ‘Public Distribution Scheme’ (PDS), the world’s largest food distribution program. Under the scheme, it dispenses grain to 800 million people – roughly a tenth of the world. How much does that come to? Well, last financial year, India grew a total of 110 million tonnes of wheat. It distributed almost a quarter of that – 26 million tonnes – mainly under the PDS.

India also runs the ‘Public Distribution Scheme’ (PDS), the world’s largest food distribution program. Under the scheme, it dispenses grain to 800 million people – roughly a tenth of the world. How much does that come to? Well, last financial year, India grew a total of 110 million tonnes of wheat. It distributed almost a quarter of that – 26 million tonnes – mainly under the PDS.

Now, this year, our wheat production might go up slightly: by 2 million tonnes. Hardly a bump when compared to 110 million. At the same time, the government will probably buy up a lot of grain – both, to replenish its granaries and to give it out under the PDS.

Why is this an issue? Well, if the government buys more grain, the market gets less of it. Only last year, government procurement had gone up by 7 million tonnes. Even though a slightly bigger harvest made up for some of this increase, the markets still saw 4 million fewer tonnes of wheat than the before.

When less grain hits the market, the little that does becomes more expensive. This can be a problem. A lot of India’s recent inflation, as we’ve noted many times off-late, owes itself to stubbornly high food prices.

Now, the government has two choices (assuming its food distribution program continues without pause). One: it lets its granaries stay at their current, depleted levels. This allows us to lower food inflation slightly in the coming year. However, our stocks remain important. Sooner or later, we’ll have a poor harvest, and will suddenly need the food in our granaries. If that happens before we re-stock, we’ll be caught with our pants down.

On the other hand, the government could brave some inflation in the short term. Of course, this will be unpleasant. Nobody likes higher prices. At the moment, though, other forces are pushing prices down. Our core inflation has fallen considerably and the RBI’s repo rate remains high. If tough decisions have to be made, there may never be a better time to make them.

How India surfs

India is on the internet a lot.

In the quarter that ended last December, India consumed 50 billion GB of wireless data alone. That’s 20% higher than last year – the fastest it has grown in seven quarters. This growth comes from two things:

One, there are more Indians on the internet. There were 8% more internet users in the December quarter than there were a year ago.

Two, Indians are on the internet more often. The average subscriber consumed almost 19 GB of data a month through the quarter. In just the last three years, the average Indian’s data consumption has gone up by 50%.

The story doesn’t stop at wireless data, though. There’s a subtle shift in how Indians are using the internet.

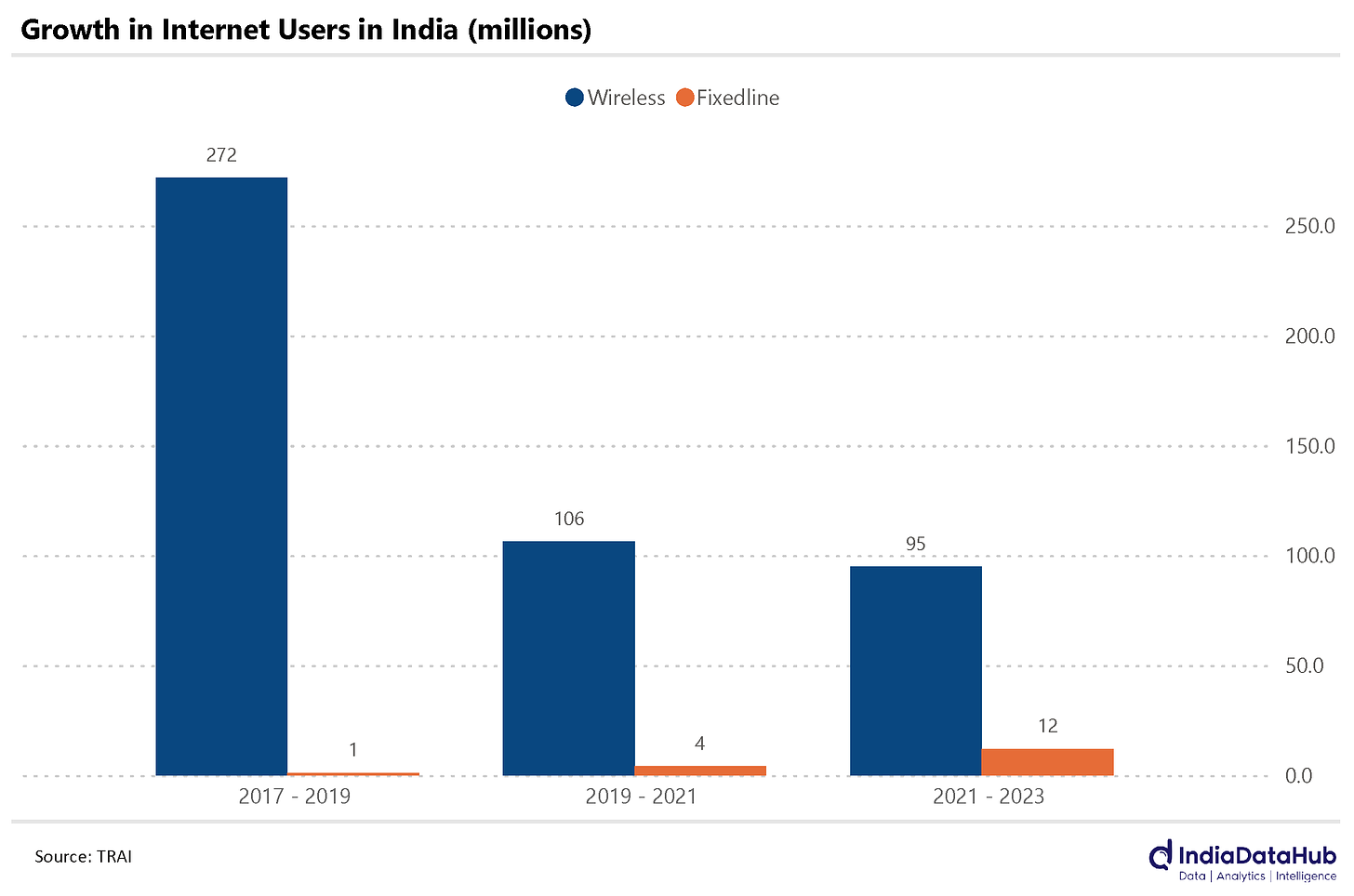

Only half a decade ago, almost all new internet connections were wireless. Since then, though, India has seen a steady increase in its ‘fixed-line’ connections – broadbands and the like. Of course, mixed-line users remain a small minority of Indians on the internet – less than 5%, in fact. But they’re growing fast. Through 2022 and 2023, for instance, India added 110 million internet users. Of these, ~11% – 12 million users – were fixed-line users. This growth is thrice as fast as it was in the two years that came before.

More building, less planning

FY 2024 been an interesting year at the Road Transport Ministry.

On one hand, it started very few new projects. Through the year, the ministry only awarded road projects worth a mere 8,581 km – 30% lower than last year, and the lowest it has been since FY 2019.

On the other hand, it was busy building. It constructed 12,349 kms of road through the year. That’s a three-year high, and 20% higher than the year before. This shows up in its spending as well. Its capital expenditure for the year was 25% higher than in the previous year, at a whopping ₹3,000 billion.

No money for old schemes

The NREGA scheme ran out of money last year. Not the government, mind you. Just the scheme.

In FY 2024, a total of ₹1,050 billion was spent under NREGA. That isn’t the problem: that’s about as much as was spent in the year before. Only, it still owes dues of ₹200 billion, for labour and material. That’s almost four times the amount that was left unpaid last year. These dues will have to be paid eventually, but that is now a problem for this year and its budget. For now, the government has kicked this can down the road, over to this financial year.

These unpaid expenses are for material and administrative costs, not wages. A silver lining – and a possible reason for these expenses being shunted down the line – is that a lot more money was paid in wages over the year. This was for two reasons: one, more work was given out under the scheme, and two, daily wage rates went up.

A poor showing for the US economy

The US just released its GDP data for the quarter that ended in March. It was sub-par. The American economy grew by 1.6% QoQ SAAR – well below the expected growth of 2.5%. It’s the slowest the country has grown in seven quarters.

(It’s beyond me to condense ‘QoQ SAAR’ in a sentence. You’re smart. You can Google it. Broadly, people look at how an economy grew over a quarter and ask “so, what would things look like if the health of the economy stayed the same for the entire year?” Then they do some fancy math, wave a wand, mutter some incantations, and voila! You have ‘QoQ SAAR’ numbers.)

Americans didn’t spend very much on themselves over the quarter. The American government, too, held back. This slowed the country’s economy down. The economy still retained a little zest because of a sudden rise in how much people spent on residential property. In all, though, this hasn’t been a great quarter.

This should give policy-makers some food for thought. Don’t expect any sudden changes, though: the American job market is tight, and that gives policymakers hope that the economy is doing well, despite a quarter’s gloom.

That’s all for this week, folks! Thanks for reading.