It’s the economy, stupid! 2 slow 2 sedate

We love India Data Hub’s weekly newsletter, ‘This Week in Data’, which neatly wraps up all major macroeconomic data stories for the week. We love it so much, in fact, that we’ve taken it upon ourselves to create a simple, digestible version of their newsletter for those of you that don’t like econ-speak. Think of us as a cover band, reproducing their ideas in our own style. Attribute all insights, here, to India Data Hub. All mistakes, of course, are our own.

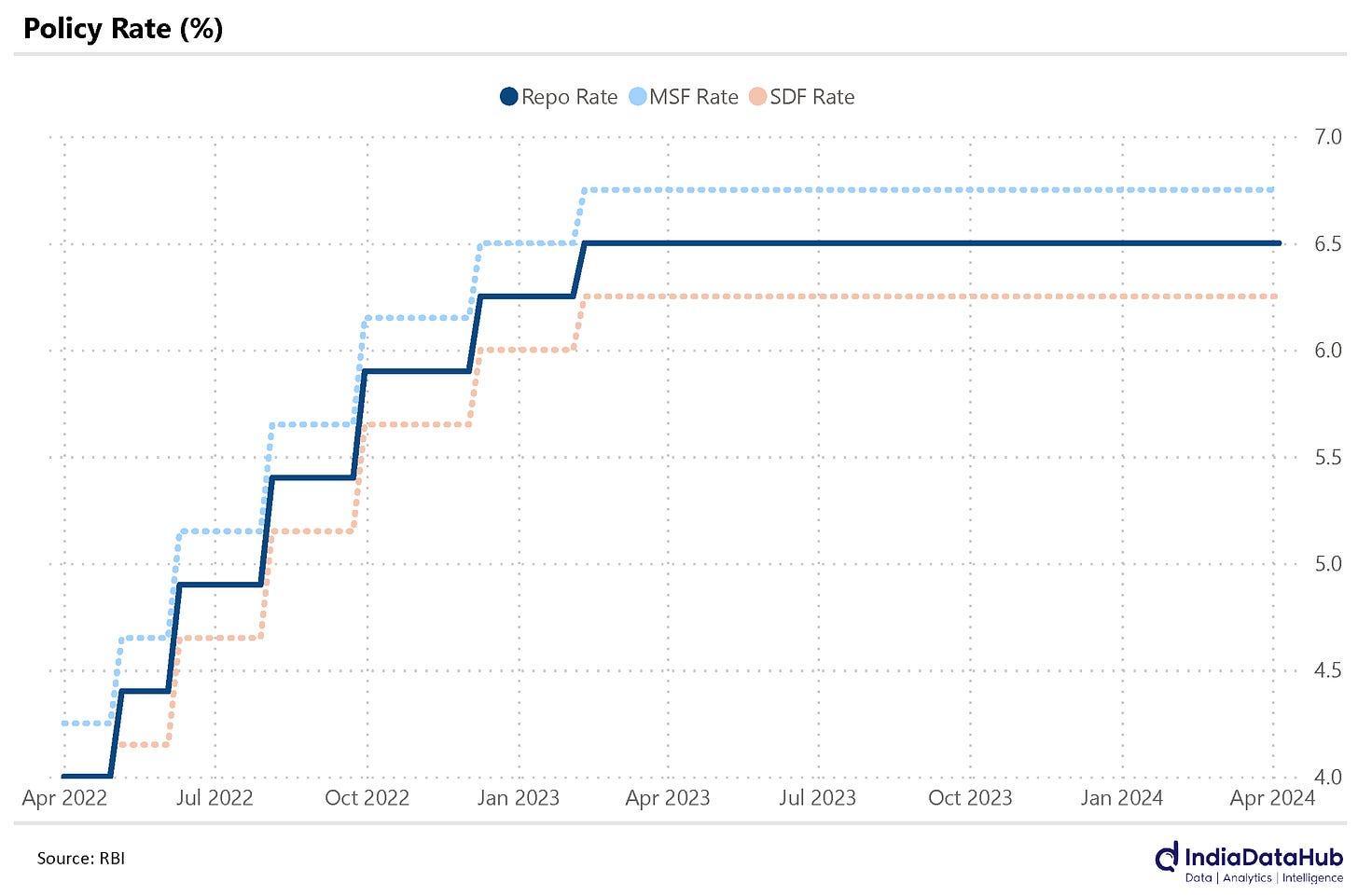

At long last, it’s over. We’ve now gone into the RBI Monetary Policy Committee’s (MPC) impending decision on repo rates for several editions on the run. Finally, last week, it conducted its long-awaited meeting. Its decision? Do nothing.

Aayein?

First, let’s recap what we’ve been through here and here. Quickly:

- The RBI controls the amount of money going into India’s economy.

- A lot of fresh money enters the economy through bank loans. Banks, in turn, must get the money they loan out from somewhere. The RBI’s repo rate sets the cost they pay for additional money.

- There are only so many things one can spend money on in the economy. When more money enters the economy than things that you can spend on, all that new, extra money chases the same few things there are to buy. That is, prices increase.

- Conversely, when interest rates are too high, people must pay through their nose to take a loan. Naturally, they’re reluctant to do so. Economic growth takes a hit.

- The RBI’s job is to curtail prices, or inflation, while ensuring that there is enough money going around. Currently, inflation is down from its peak, but has been a little stubborn. Meanwhile, the economy is growing well, even though its momentum may have flagged a little off late. One should expect rates to be cut soon-ish, but there’s no telling when.

Those are the basics you need. Now to last week’s meeting.

Is this even a big deal? Wasn’t it that nobody thought any rate cuts would happen this week?

Yeah. And they were right. The MPC hasn’t moved rates around at all. Just like it didn’t in its last many meetings, as this graph will tell you.

(For reference, the MPC meets once every two months, roughly speaking.)

No surprises there… except one: people thought the MPC would at least tell the world that it was thinking about rate cuts. The markets would take this into account and ready themselves for one before the MPC’s next meeting, in June. That’s when the actual rate cuts would happen. The markets would be prepared for this possibility, and take them in their stride. It would all be smooth, people imagined, like clock-work.

Let me guess. That didn’t happen?

No, it didn’t. Instead, the MPC merely doubled down on its commitment to fighting inflation. In its words:

“Monetary policy must continue to be actively disinflationary to ensure anchoring of inflation expectations and fuller transmission.”

Of course, there’s nothing that stops the RBI from slashing rates anyway in June. It doesn’t have to tell markets anything. But, at least as things stand today, it probably will. There’s simply no need for it to spring surprises and throw people off their guard.

If this is correct (and we’re just gazing into crystal balls, here), the earliest we should expect a rate cut is at the MPC’s meeting in August. The meeting before that – in June – will probably be used to tell the markets about a change in its intent.

Or maybe it just does nothing again.

What’s the deal, though? What’s on the RBI’s mind?

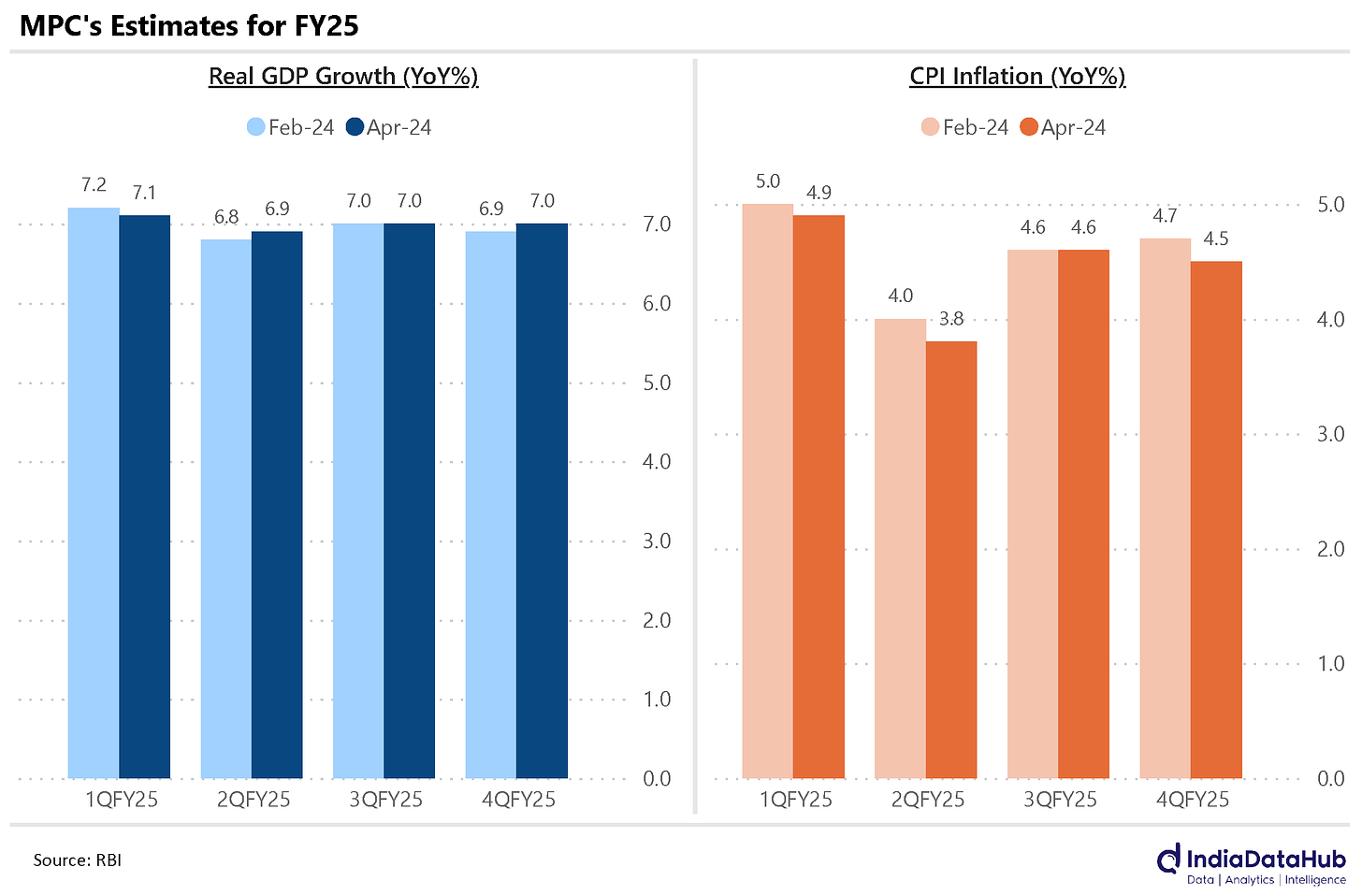

For one, the RBI thinks India’s economy is pretty strong right now. The MPC has forecasted robust growth of 7% this financial year. While that’s a little lower than last year’s 7.6%, it’s still pretty great. With things going this well, the RBI feels no pressure to push the economy higher by cutting rates.

At the same time, the RBI’s high interest rates have reigned prices in. The MPC now thinks inflation will come down to 4.5% this financial year, from 5.4% last year. By law, the RBI targets inflation of 4% per year.

At the same time, the RBI’s high interest rates have reigned prices in. The MPC now thinks inflation will come down to 4.5% this financial year, from 5.4% last year. By law, the RBI targets inflation of 4% per year.

And so, to the MPC, things are in perfect balance right now. A robust economy is allowing it to comfortably do its primary task – of keeping prices in check – and it’s doing a pretty good job of that. Bottom line: there’s no need to rock the boat.

There’s some new high frequency data for March. And it looks a little mixed.

What data, again?

‘High frequency data’. We’ve been over this before. From last month:

“Those are little bits of information on the economy that we can gather regularly and quickly.

Think about it: nobody really understands how an economy is doing. Economies are impossible to grasp. They’re made of billions of transactions – people buying coffee, or filling petrol in their bikes, or picking up a copy of the day’s newspaper – each thing, each day, for each person and each business, taken together. If you really want to understand an economy, first, you must know every last thing that happens in the country.

The best we can do is look at proxies. We take the small trickle of data-points we can get – the ‘high frequency indicators’ – and use them to make whatever conclusions we can. They’re not perfect, but they give us a crude, low-resolution picture of the country’s economic activity.“

Mm-hmm. So what does it say?

We’ll start with vehicle sales. From last month, once again:

“People always need vehicles. But vehicles are huge purchases, not made on a whim. People buy them when they have money to spare and feel confident that things look good in the foreseeable future. As a whole, then, Indian automobile sales tell us how good Indians feel about their economic prospects.”

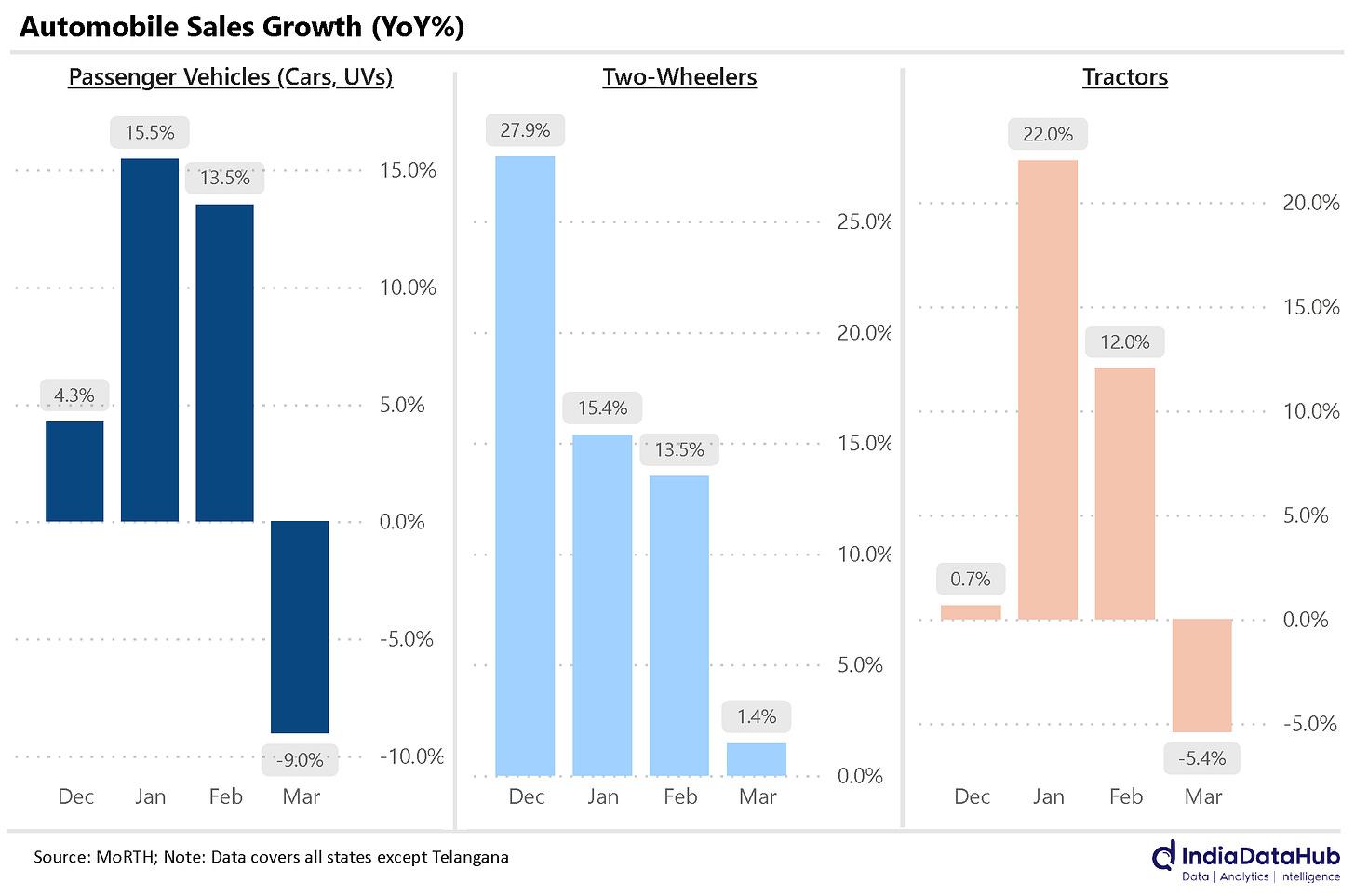

Going by that, Indians weren’t feeling too confident about their prospects in March. Here’s what we saw:

- Passenger vehicles (that’s cars, utility vehicles and the like) aren’t doing too well. This March, sales were 9% lower than in March 2023. This was the first time that sales fell, year-on-year, since July 2022.

- Two-wheelers saw tepid growth in March as well – of a mere 1% over March 2023. For context, they were growing in the double digits for four straight months before that.

- Tractor sales fell by 5% in March, compared to March last year. That, too, came after two straight months of double-digit growth.

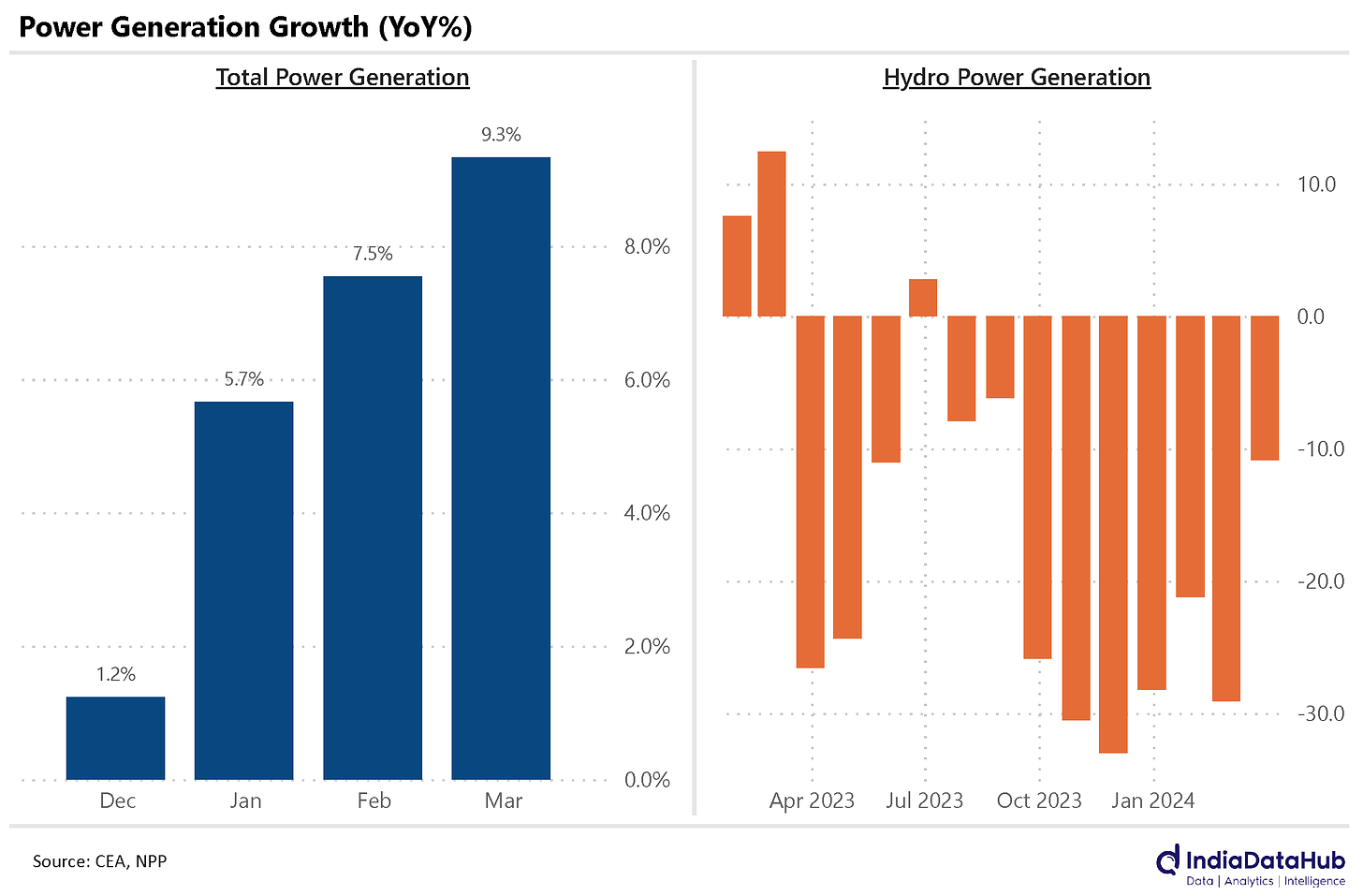

On the other hand, the data on power generation is a little more heartening.

On the other hand, the data on power generation is a little more heartening.

There’s a lot that simple power generation can tell you about an economy. You need power to run all sorts of things – offices, factories, machines – you name it. If India needs more electricity, Indians are probably up to a greater number of useful things.

This March, India generated 9% more power than it did in March last year. That’s a little faster than the 7.5% growth we saw in February.

Is all this green power? Or are we just pumping out more greenhouse gases?

It’s certainly not all green power. That’s growing as well, to be fair – power generation from renewable sources was up by 12% last month, compared to March last year. But we still rely greatly on fossil fuels.

There’s one green(-ish) source of energy that’s clearly taking a beating. Decades after Prime Minister Nehru termed dams the “temples of modern India”, two things are clear. One, temples are evidently the temples of modern India. Two, dams aren’t quite as crucial to our electricity generation as he may have hoped.

The use of hydroelectricity has fallen precipitously over the last year. Of the last 13 months, its use has gone down in 12. Over the last year, on an average, hydroelectricity was used 20% less than it was in the year before. The shortfall was met by thermal power, the use of which was 10% higher, last year, than the year that came before.

Remember how glad we were, last month, with India’s sudden growth in services exports in January? Back then, India made so much money selling services that it almost made up for all the things we import from abroad.

U-huh. What about that?

Well, the party’s over. At least for now.

This February saw a far more timid growth of 3.5%, year on year (which might look larger than it is, because February had an extra day this year). For context, our services exports had grown by 11% in January. Yeah, regressions to the mean are a real party-pooper.

That said, our imports in services only grew slightly, by 1.8%. As a result, our services surplus (that is, exports minus imports) grew by a respectable 6% – to US$ 13 billion.

There are two new stories on inflation, this week. A good one and a bad one.

Can we start with the good one, please?

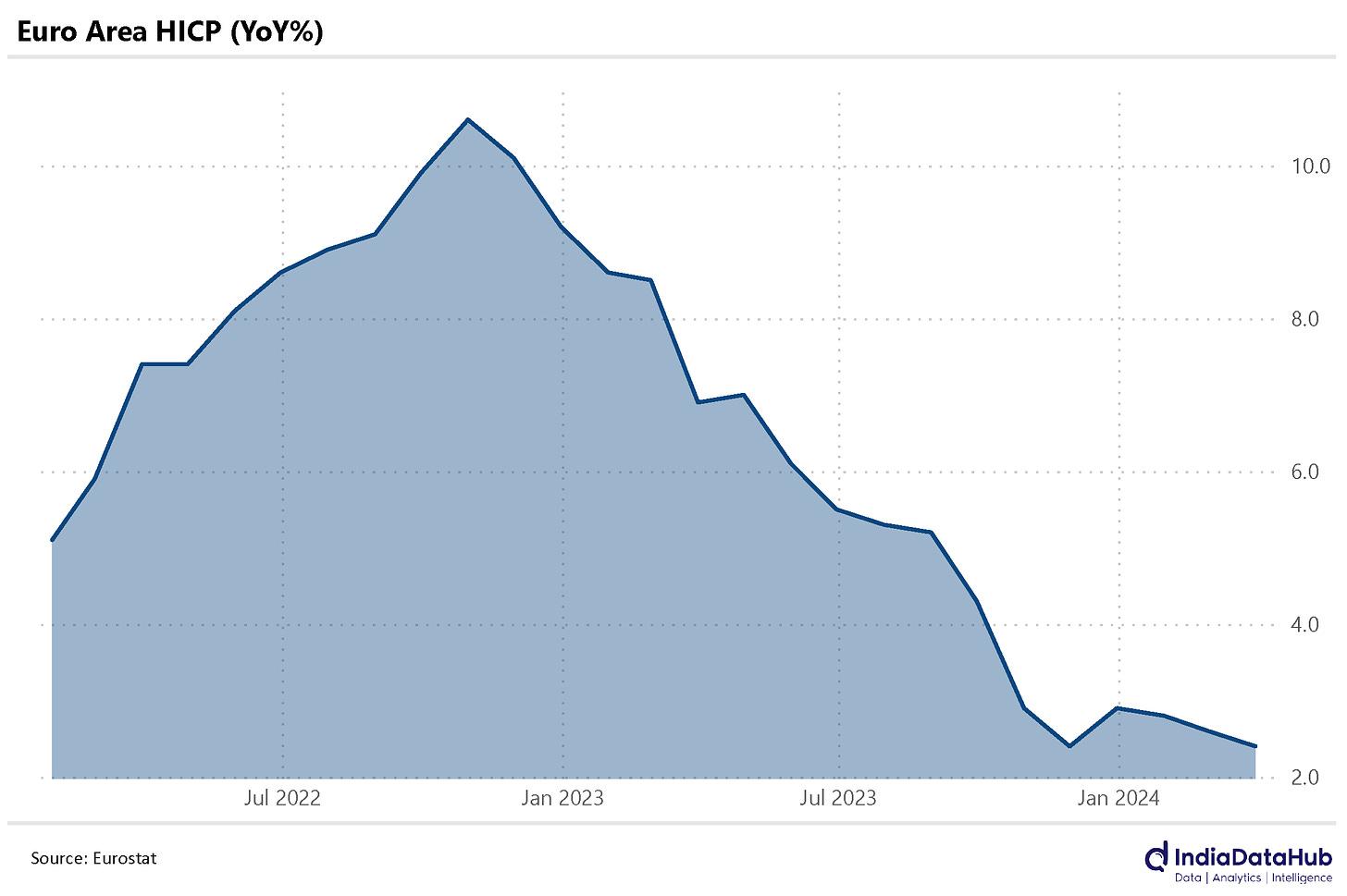

Sure. Europe is en route to bringing inflation back in control after a tumultuous few years.

Europe (or more accurately, the “Eurozone” within Europe – all those folk that use the “Euro” as currency) released surprisingly good inflation data last week. Inflation came down to 2.4% in March, below February’s 2.6% – possibly because energy became a little cheaper in the month.

To give you a sense of what an achievement that is, look at the graph below. A little more than a year ago, Europe had touched double-digit inflation. It’s now closer to its official target of 2%: which it last met all the way back in June 2021.

Not bad. What’s the bad one, now?

Not bad. What’s the bad one, now?

Turkey is in a really bad place. In March, it saw a 16-month peak in its rate of inflation: 68.5%. You read that right. 68.5%.

This isn’t a sudden aberration – Turkey’s has seen absurdly high inflation for a long while. Last March, for instance, its inflation was at 50%. The March before that? 60%. In just three years, things have grown to cost 4 times as much. That is, if a loaf of bread cost 25 lira in March 2021, you can buy it for no less than 100 lira now.

This is just one symptom of a sustained economic crisis for the country, which has lasted for the greater part of a decade.

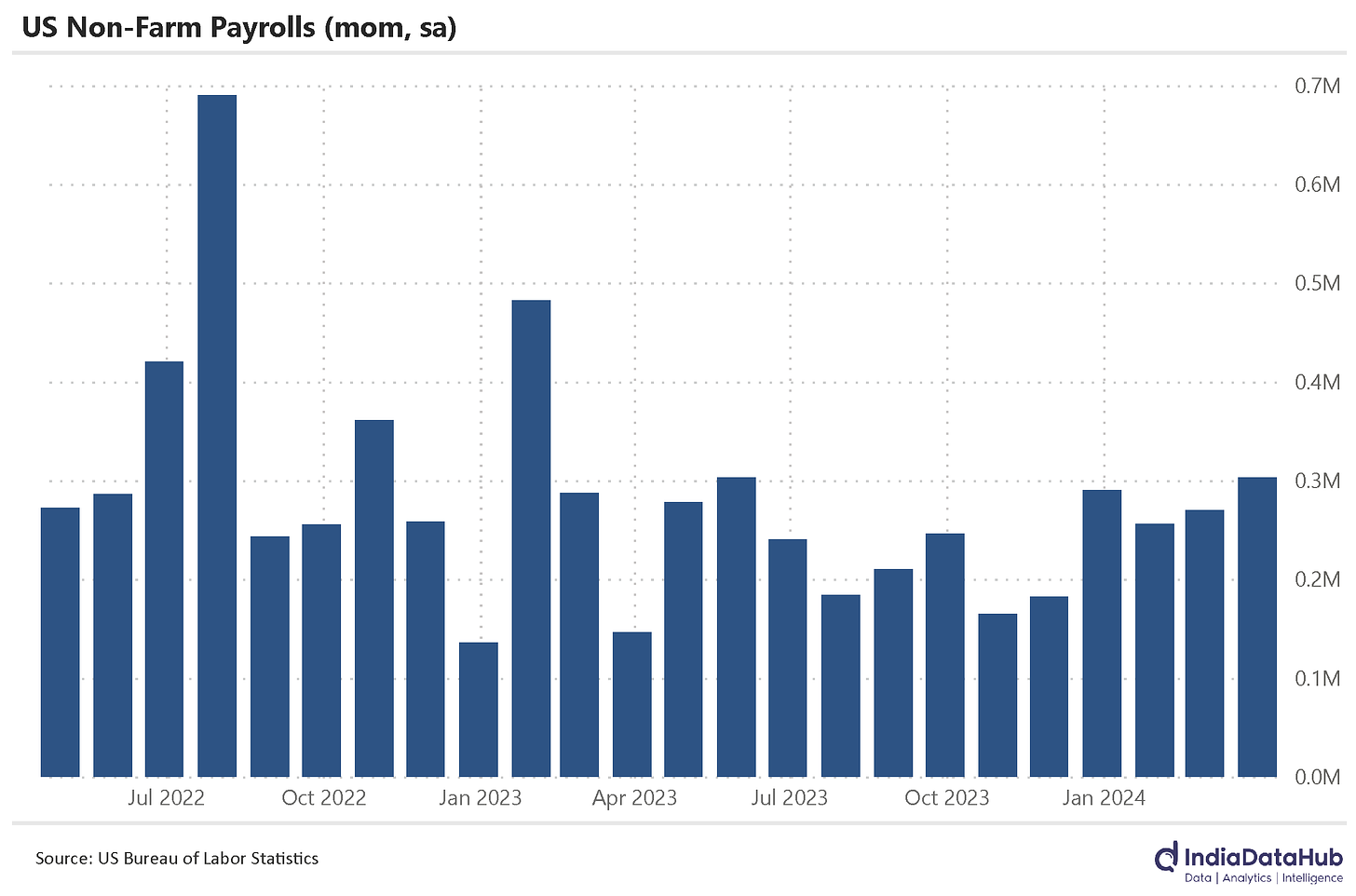

And finally, the US creates yet more jobs.

Great, this again… I mean, good for them!

The American economy created 303,000 new non-farm jobs in March. This is massive – well over the 212,000 that people forecasted. It’s the most jobs that have been created in any month since May last year.

As an added bonus, they revised the data for January and February. Turns out, while February had created 5,000 fewer jobs than they thought, January had created 27,000 additional jobs. In all, the American economy had created 22,000 more jobs than we thought.

So many jobs going around. I wish they gave me one.

They definitely have a strong labour market these days.

The US Fed, meanwhile, is mulling over the same questions as the RBI – should they cut rates to boost the economy, or should they continue pressing inflation down? The fact that America is adding an ever-greater number of jobs will give the US Fed more confidence to pursue the latter, and carry on with its high rates. The markets have taken note – and are assigning a probability of only slightly more than 50% that there will be a rate cut in June.

Rate cuts by the US, in turn, affect the RBI’s decision on rates: for reasons we’ve explored before.

That’s all for this week, folks. Thanks for reading!

If debt monetization occurs in USA, what will happen to USDINR Value?