It’s the economy, stupid! The future of Indian telecom is… BSNL?!

We love IndiaDataHub’s weekly newsletter, ‘This Week in Data’, which neatly wraps up all major macro data stories for the week. We love it so much, in fact, that we’ve taken it upon ourselves to create a simple, digestible version of their newsletter for those of you that don’t like econ-speak. Think of us as a cover band, reproducing their ideas in our own style. Attribute all insights, here, to IndiaDataHub. All mistakes, of course, are our own.

Strange things afoot in telecom

Hey you! Without looking at the rest of this post, try answering two questions: (a) where’s the Indian telecom industry headed?, and (b) where is BSNL headed?

If you’re anything like me, your answers are probably: (a) the private sector is growing at breakneck speed, adding subscribers by the millions, and (b) BSNL’s best days are behind it, and it’s probably on its last legs.

This month’s data, then, might surprise you, for two reasons:

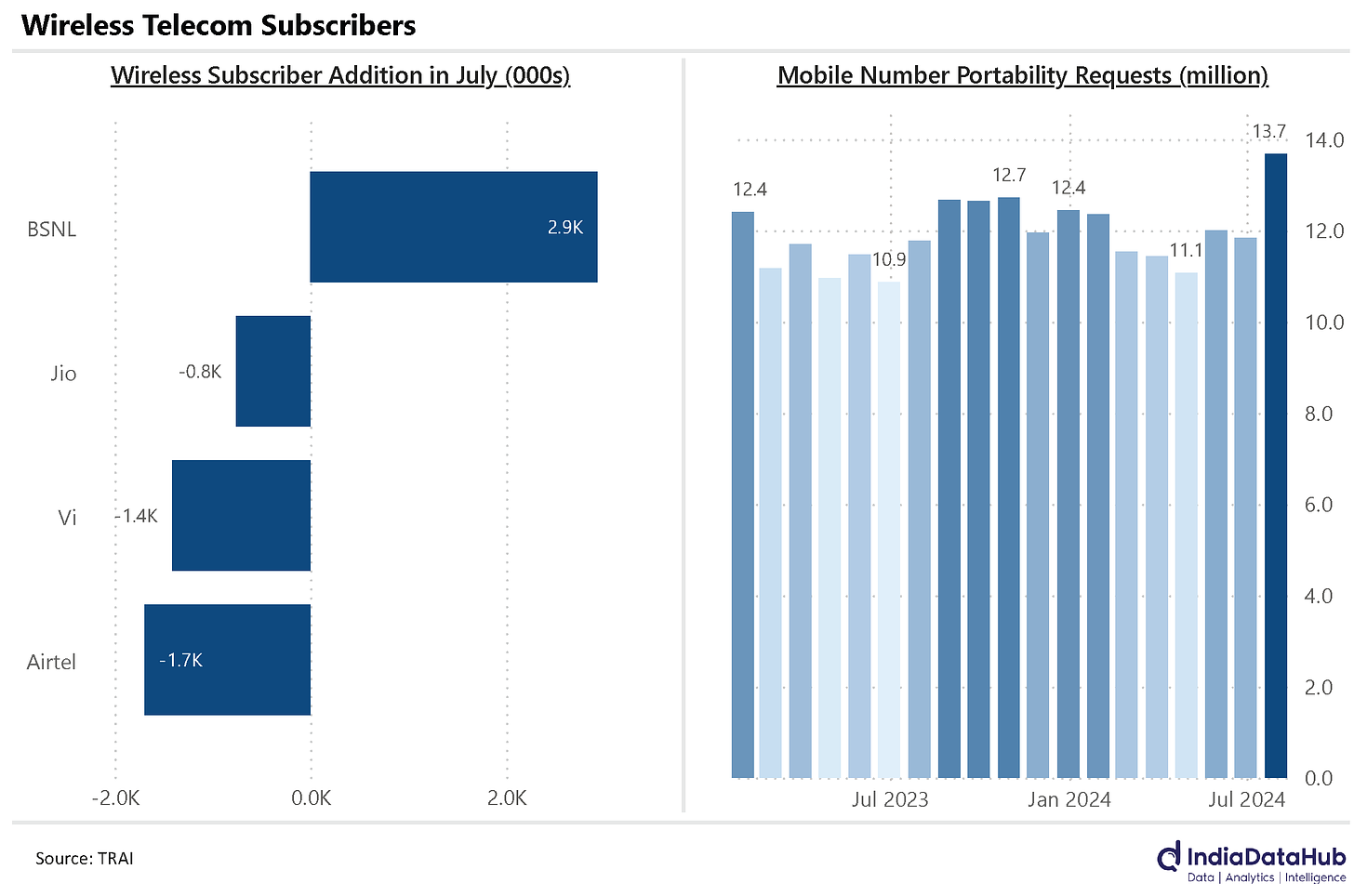

One: telecom operators, together, lost a million subscribers in July! What’s more — it’s private entities that took the hit. Airtel lost 1.7 million subscribers – 0.4% of its subscriber base. Vodafone-Idea lost 1.4 million, or 0.7% of its subscribers, while Jio lost 0.8 million, or 0.2% of its subscribers. This is unusual. Private telecom operators don’t lose subscribers easily. Jio, for instance, last shed customers in February 2022. For Airtel, that came even before, in October 2021.

Two: While the entire industry was losing customers, BSNL was raking them in. In a single month, BSNL added three million subscribers. That’s massive: 3.5% of its entire subscriber base, in just one single month!

This begs the question: why? What’s turned the whole trajectory of the industry on its head?

Well, late this June, most private telecom companies hiked their rates by 15-25%. BSNL, however, didn’t do so. What followed was a flood of number porting requests — 2 million more than average, in fact — with many people asking to move their connection to BSNL. Seemingly, in the space of a month, the most price sensitive telecom customers all shifted to BSNL, or dropped out altogether.

This is why most of the decline has come from rural India. Urban India, in contrast, actually added half a million subscribers.

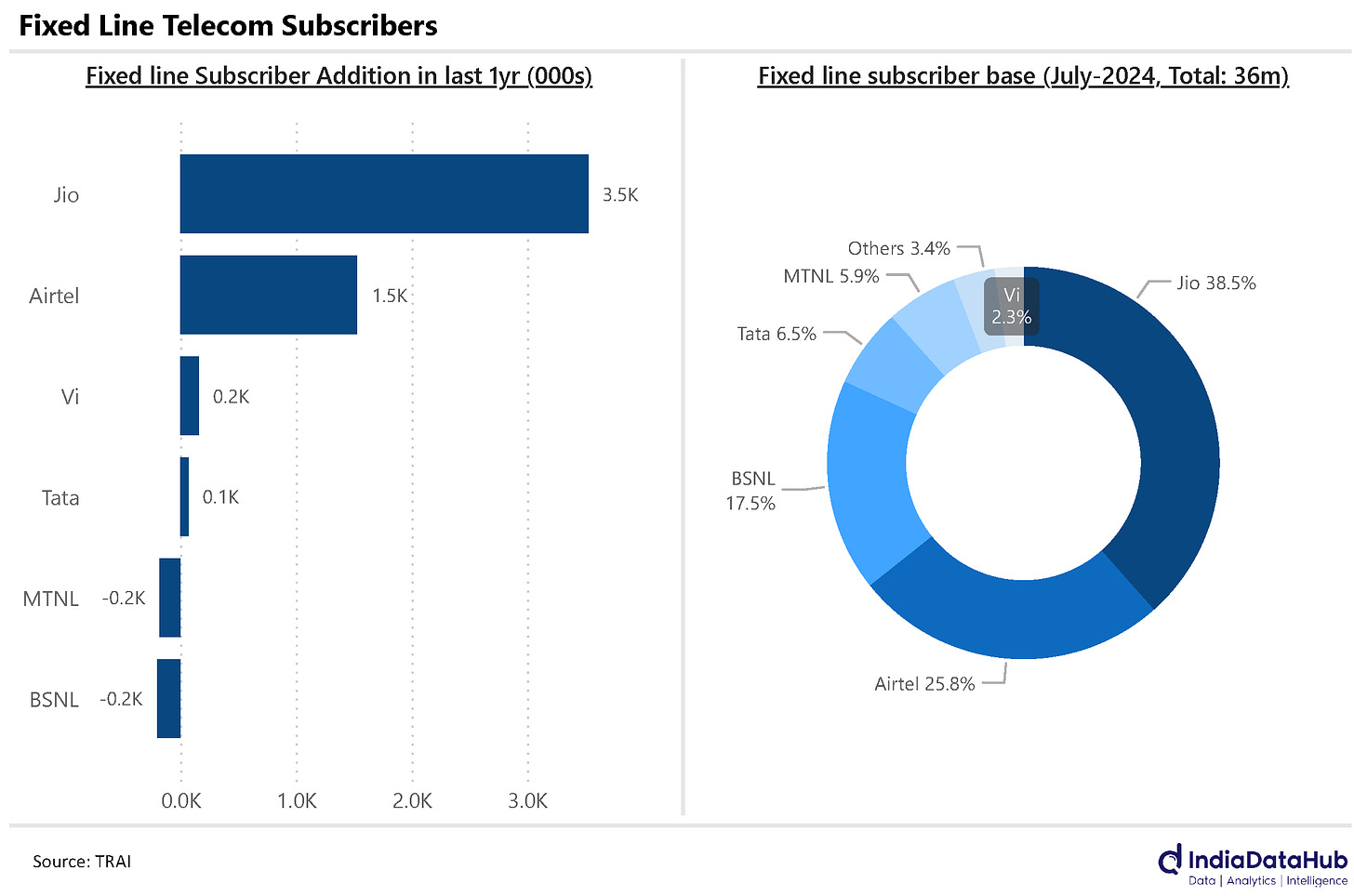

The fixed line business (landlines, broadbands… you know, wired stuff) presents a contrasting picture. It has moved exactly as expected.

Jio’s growing particularly fast, adding 3.5 million new customers over the last year — a ~35% bump in its subscriber base. The rest of the industry is struggling to keep up with the behemoth. In fact, Airtel, Vodafone-Idea and Tata, put together, have barely added half as many customers as Jio. (And that, too, is only because Airtel alone added 1.5 million new subscribers.)

So, Jio is beginning to dominate the fixed line industry as well, with a market share that’s nearing 40%. It now has 4% more of this market than what its key rivals — Airtel, Vodafone-Idea and Tata — collectively hold.

Exports decline

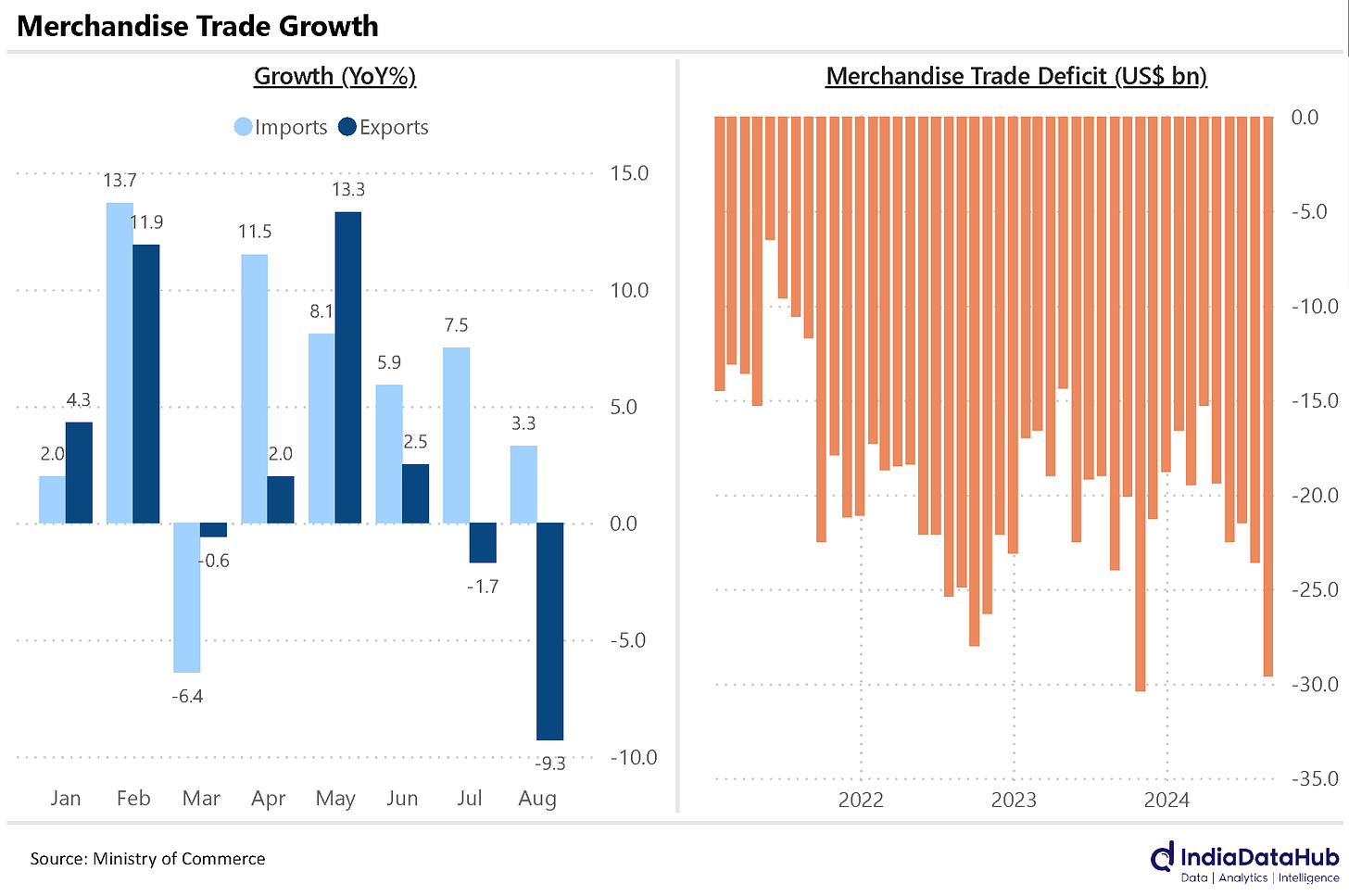

This August, India’s goods exports fell for the second month in a row. In July, they’d fallen by 1.7%, year-on-year. In August, though, the decline was far more severely — 9.3% year-on-year.

At the same time, we imported more than usual; our imports grew by 3.3% year-on-year. This has widened the gap between the two — our ‘trade deficit’ — to US$ 30 billion. That’s the second highest trade deficit we’ve ever had, the first being in October last year.

So, why are we suddenly exporting so little? Well, a lot of that decline comes from the petroleum sector. As economies across the world slow down, they need a lot less petroleum. Simultaneously, this pushed down oil prices, while our oil shipments, too, took a hit. The impact is evident. Our petroleum exports have fallen by a massive 40% year-on-year.

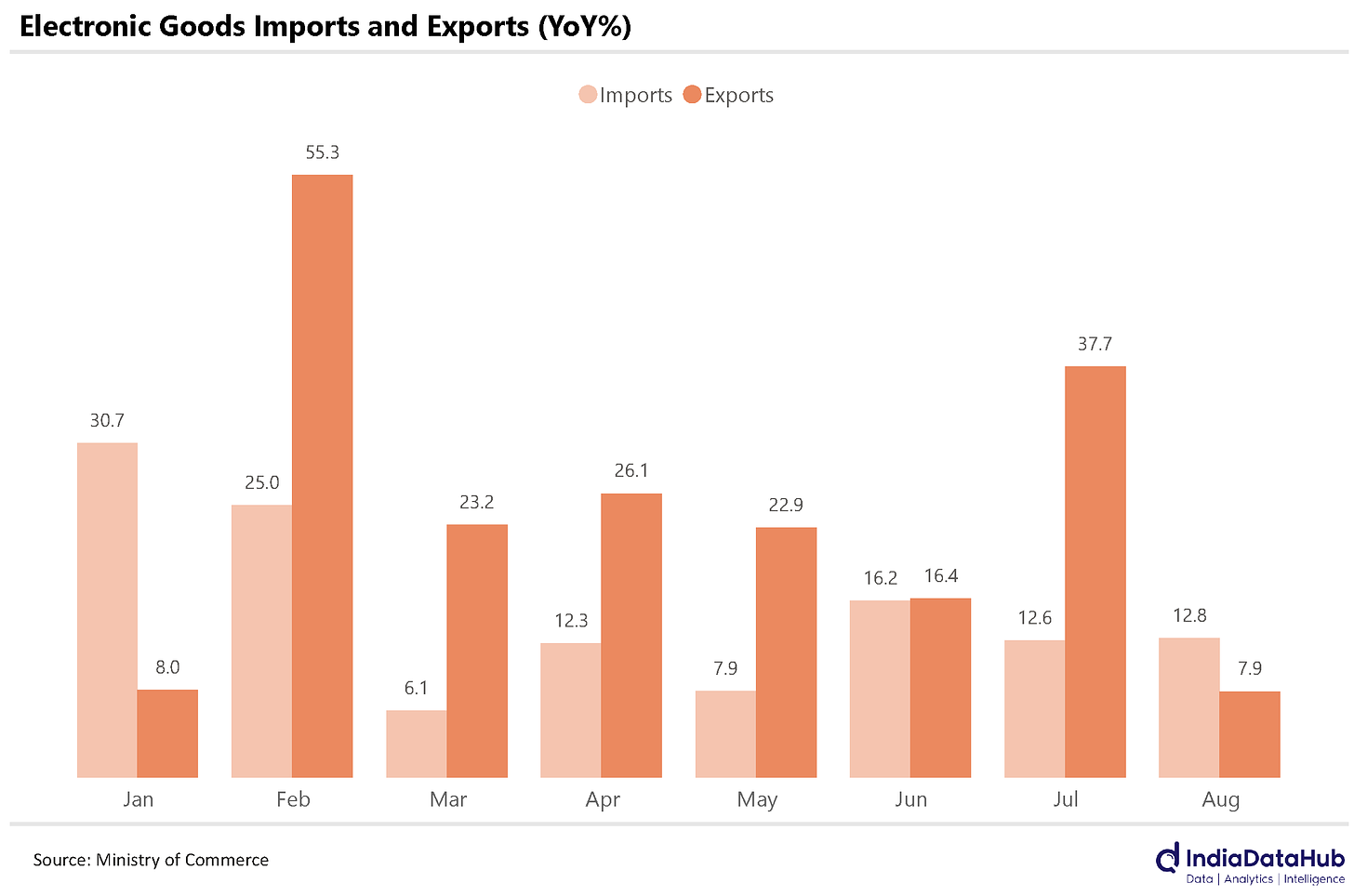

One of the other big areas where we’re trying to push exports is electronics. Until August, we’d been remarkably successful at it. To be fair, our electronics exports increased in August as well. But while our exports were growing faster than our imports for a lot of the last year, in August, this trend reversed. For the first time in months, our imports left exports behind.

Now, this could all just be noise in the data, instead of suggesting some sort of worrying trend. For instance, we make a lot of iPhones, and the iPhone 16 just launched in September. For all you know, we spent most of August making the new iPhone model to sell after the launch. If that were the case, our electronics exports could surge again in September, and this little blip will be forgotten. Stay tuned.

The Fed cuts rates

Last week, we talked about how the US Fed cut interest rates by 0.5%. This was its first rate cut since 2020.

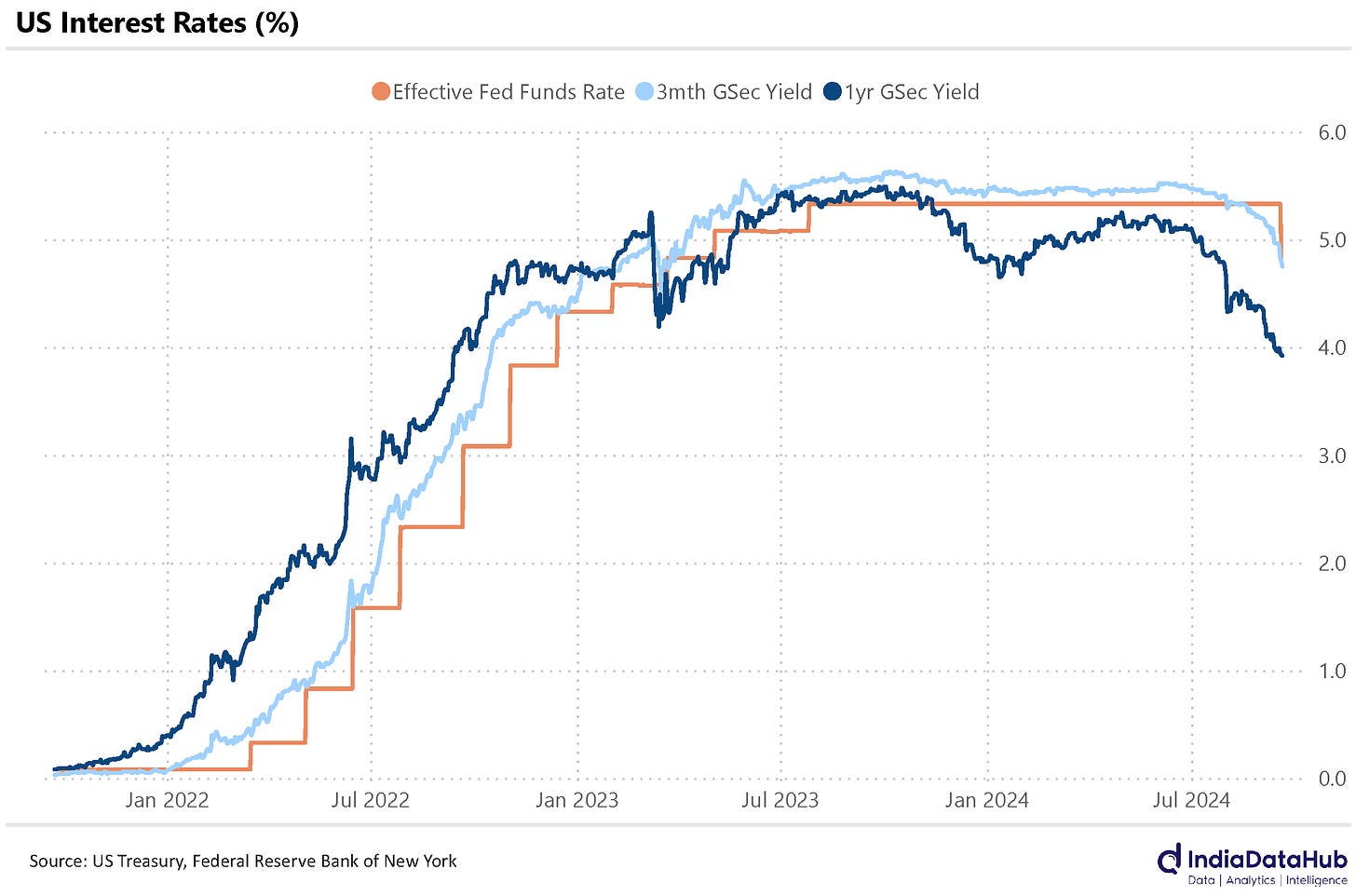

What now? Well, people expect more rate cuts to follow. While the effective Fed funds rate — the economy’s actual cost of funds — is now at 4.83%, US 3-month treasury bills are trading at a lower yield of 4.75%. That is, people are lending money to the US government at a rate that’s cheaper than the economy’s actual cost of money. This usually happens when people think the Fed will soon bring the cost of money lower.

At the moment, the markets expect the Fed to cut rates by an additional 0.5% in November.

Now, what does a Fed rate cut mean for India?

One: it changes the calculus for the RBI, as we explained last week. When Dollars become more abundant, that impacts everything we buy or sell for Dollars. That doesn’t, however, mean the RBI will slash rates too.

The RBI is looking at a very different situation from the US Fed. While prices have flattened in the US, Indian inflation, as we saw last week, is beginning to pick up. The Indian economy also looks a lot more exciting than the US, where a weak labour market has spooked people about a possible recession. If anything, the Indian economy might be a little too excited: which shows up, for instance, in people getting too comfortable with taking personal loans. All in all, though, it doesn’t look like the economy is dragging under the weight of high interest rates.

This gives the RBI more breathing room to keep rates high.

Two: this makes Indian markets more attractive to invest in, and foreign markets more attractive to borrow from.

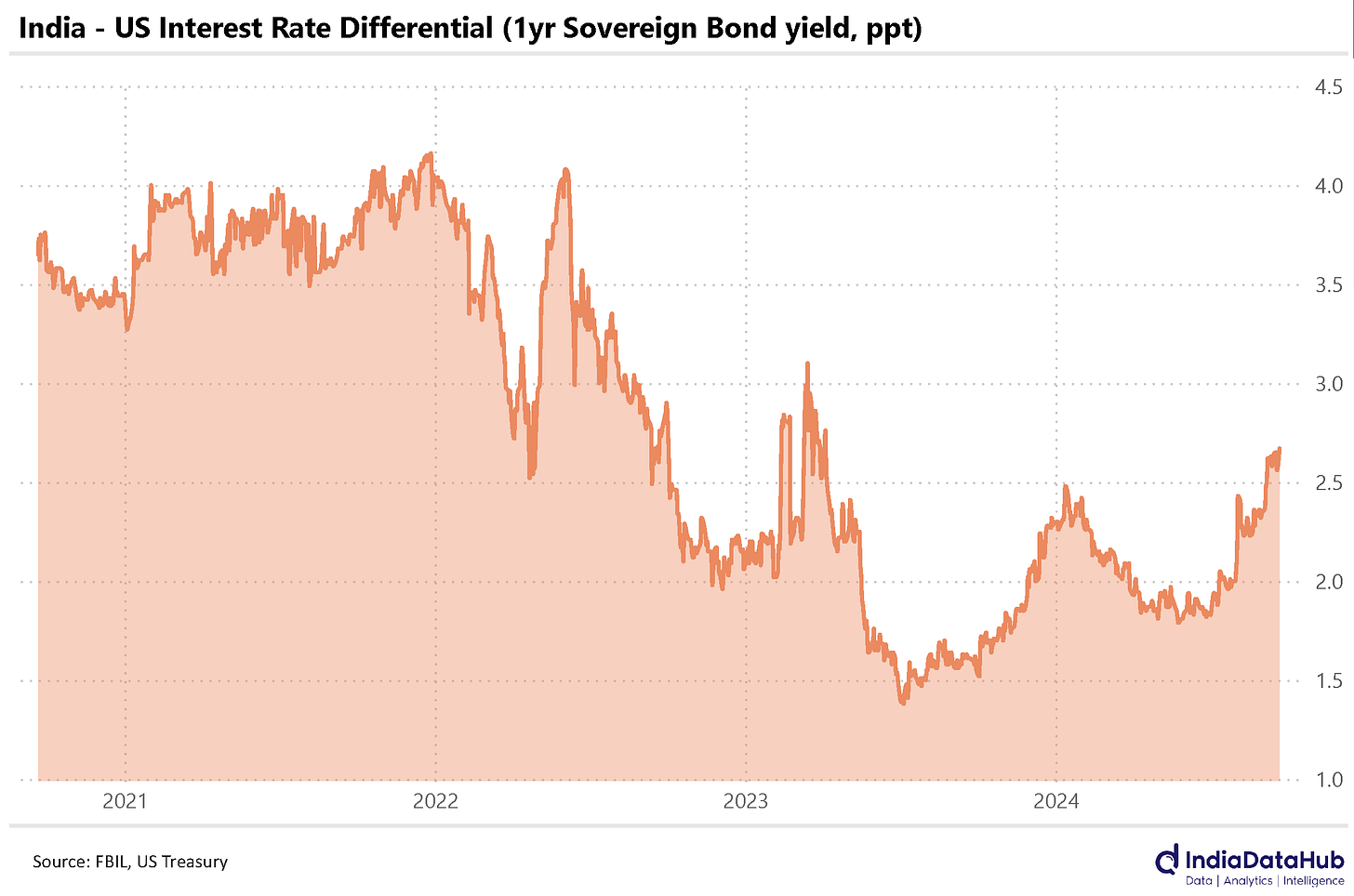

The government bonds of stable countries are generally safe investments. Whether you’re lending money to the United States or India, you generally expect to get your money back. But what you can earn from your lending is changing. In May, you’d make an extra 1.8% if you bought Indian 1-year government securities, compared to US 1-year government securities. Now, you’d make 2.7% more. To a lot of investors, Indian government bonds simply make more sense. So, you can expect more money to flow into India.

Now, as money comes into India, that pushes up demand for the Rupee — effectively making it more expensive relative to other currencies. To a foreign investor, that creates a nice little bonus on their returns. And that can pull in even more money.

Over time, though, fundamentals are all that matter. All the foreign investment India receives is a reward for running the economy well. For more investment, we need more of that.

That’s all for this week, folks!

As much as I love reading this, I do miss the Financephobic series.