Here we go again…

Hi there. It’s been a while since we spoke. Or at least it feels that way.

When we last spoke, things were less bad. I’m not just talking about The Cheeto Salesman becoming the president of the Disunited States of Amrika — I’m talking about the markets. Two months ago, when I last wrote here, the dying embers of the bull market were still hot. But now, those embers are, well… just look at this damn chart:

Yeeep. It’s a bloodbath.

So… how are you doing? Is your mental health OK?

Look, I’ve been writing about bear markets since 2022. Don’t judge me. I don’t want your financial ruin — I just think it can happen. I’m not an astrologer either. You don’t need magical powers to see that lines on a graph can go down some day. I haven’t been calling for bear markets, nor have I been predicting them.

I’ve just been oozing my wisdom on how to survive a bear market when it finally came, all through this blog:

How to survive a bear market? — February 14, 2022

God, give me the strength to buy and hold—April 25, 2024

You have to get punched in the face to know how it feels—May 24, 2024

Basically, whenever the markets felt jittery, I would thrash out long blogposts dripping with my juicy, moist wisdom (Fiiine, I know I’m being disgusting, I’ll stop) to save retail investors from their thoughtful and well-planned stupidity. And then… nothing. It didn’t matter if Russia threatened to flatten Europe, Iran threatened to launch nukes, or Israel tried its best to kickstart WWIII — the stonk market continued hurling itself towards the dark side of the moon with great enthusiasm.

My wisdom-ous posts, oozing with sticky advice (Haha psych! Ok, this is the last one, I promise) on how to survive the bear market, were all left unheeded. But finally, dear people who are disappointed that the stonk market has the temerity to fall, it seems like the bear market I was watching out for is finally here.

I know you are in a state of disbelief. There’s been so much to process:

- You’ve finally discovered that the stock prices can actually fall.

- You learnt that when the market falls, so do all those “fundamentally great” stocks you picked after your thorough, time-consuming, research process of asking your friends and listening to mouth-breathing internet idiots.

- You learnt that it was a bad idea to pick stocks after watching Reels in which a Haryanvi guy spat out words like “momentum” and “support”, while his fingers danced angrily from north, to south, to east, to west.

Don’t worry. I am here for you.

I mean, I’m not gonna give you money or anything. But I will, if you’ll permit me (actually, I don’t care either way) offer you some gyan. See, there are five states of grief. First comes denial, then anger, then bargaining, depression, and finally acceptance. Right now, you’re probably early in this process. Maybe you’re raging at me for even suggesting that things are bad.

But don’t worry. The markets are probably going to get much, much worse before they get better.

Hey, nobody ever said the “India growth story” will be painless.

By the time you finish reading this post, I’ll hopefully drag you — like a petulant child who doesn’t want to eat vegetables — from being angry, to being depressed, to accepting that this too shall pass.

How bad are things?

First, let’s take a step back and understand where we are.

You’ve probably already seen how far the big headline indices have fallen. At the point at which I’m writing this, Nifty 500 is down 15%, Nifty midcap 100 by 17%, and Nifty smallcap 100 by 20%. It’s not a pretty picture. But we won’t re-hash that. Instead, let’s drill down further.

Here’s the distribution of drawdowns within the Nifty 500. The average drawdown of the index is 30%, but this average hides a lot of variation. Dig deeper, and you’ll see that some stocks are down by as much as 60%. This is across the board: good stocks, bad stocks, low valuation, high valuation — it doesn’t really matter. There’s been a correction across the board.

This is the story of every sector. I’ve grouped the NSE 500 stocks by industry and plotted the average drawdown, just to give you a sense of how uniformly terrible things are:

Another way of seeing this is to look at sector and thematic indices. Everything looks bad. But a few indices — defence, realty, media, PSU banking, and oil — have been a real dumpster fire.

Ultimately, while some segments of the markets are worse than others, it’s been bad all around. You could look across the breadth of the market to see how things have been. The smart way to measure breadth is to look at the number of stocks above their 200-day moving average, but… I’m too lazy to do that.

A quick and dirty way to do the same thing is to look at how equal-weight indices are performing. Here’s Nifty 100 market cap weighted vs. Nifty 100 equal weight. The cap-weighted index is down 16% while the equal-weighted index is down 19%.

So, no matter how you slice things, the markets are in bad shape. We’re in a real bear market.

But bear markets come in all sorts of shapes and sizes. For all I know, the markets might recover next week. But they could also go south for a long while. How bad can it get? Well, let’s look at some charts.

Here’s a drawdown chart of Nifty 500, Nifty Midcap 100, and Nifty Smallcap 100. Look at the dotted lines at the bottom of the chart; they represent the worst falls we’ve ever seen.

I know things look bad right now. But I want you to zoom out and really look at that last line. See how far it is from the dotted line at the bottom. And then, think of how much further it can go. Sure, your portfolio looks bad today, but it could’ve been much worse. The funny part is we saw worse just a few years ago — when the COVID-19 pandemic just began — but things bounced back up so fast that we’ve already forgotten about it.

Another way of looking at this is the length of the drawdowns. That is, how long have indices spent below their peak?

Look at that tiny triangle at the very end. That’s where we are. Right now, we’ve only seen about 150-odd bad days. I know that’s about 5-6 months, but I say “just about” because, going by what people were saying only a few months ago, I’m assuming most of you invest for the “long term” and don’t think 6 months is long term.

You don’t, right? I mean, I would be terrified for you if you did.

You might already be tired of the markets looking red all the time. Doesn’t matter. A quick look at the past would tell you that things can stay bad for years at a stretch. You have to be prepared for anything.

Why are the markets falling?

Psst, I know the real answer. But you’re not going to like the answer. Are you ready? Drumroll please. The markets are falling becaaaaause…

…there are more sellers than buyers!

Didn’t like the answer?

Ah, well. If you prefer being precisely wrong over being roughly right, let me give you all the other sexy ‘analytical’ reasons that you’ll hear from other people.

Reason 1: The Indian markets are bloody expensive

For a few years, the post-pandemic returns of the Indian markets were spectacular, to say the least — especially when you looked at mid- and small-caps. If you blindly picked random stocks in late 2020 or 2021 and held on to them, you would’ve made some serious money. In fact, you would have to do something spectacularly stupid to lose money — and it would’ve been tough even then.

Thanks to this spectacular performance, the Indian market is now among the most expensive in the world.

You might be thrown off a little if you use PE ratios of Nifty indices for this purpose. There was a recent methodology change there. They went from using standalone earnings to consolidated earnings. Basically, a P/E ratio divides a company’s stock price by its per-share earnings — only, they started adding the earnings of subsidiaries and associates to the denominator as well, which made these ratios all look smaller. I’m not sure that looking at this data is of much use any more.

Luckily, professor Aswath Damodaran does God’s work, calculating this manually for the entire aggregate market — and not just by index.

In the post accompanying this data, here’s what he wrote:

The perils of investing based just upon pricing ratios should be visible from this table. Two of the cheapest regions of the world to invest in are Latin America and Eastern Europe, but both carry significant risk with them, and the third, Japan, has an aging population and is a low-growth market. The most expensive market in the world is India, and no amount of handwaving about the India story can justify paying 31 times earnings, 3 times revenue and 20 times EBITDA, in the aggregate, for Indian companies

Now, all valuation indicators have their own issues. But among the bunch, I prefer looking at the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio (CAPE), which averages inflation-adjusted earnings. Professor Rajan Raju of IIM also does God’s work by calculating this for the Indian markets. Here’s the latest reading: at 40, the Nifty 500 CAPE ratio is far above its long-term averages.

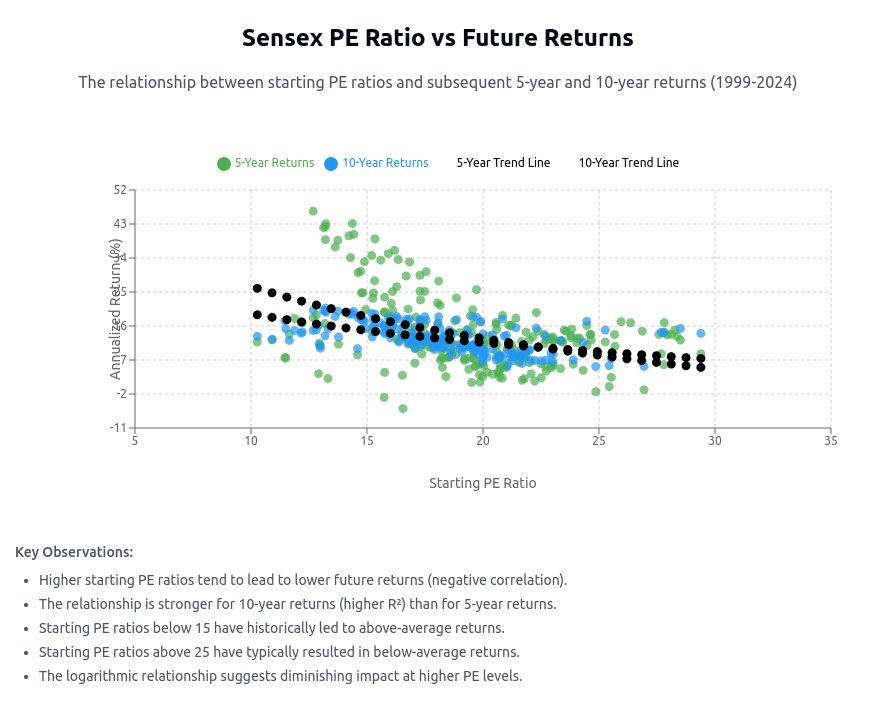

As Larry Swedroe says, valuations are a self-healing mechanism. When valuations are high, future returns are low, as the markets adjust. We’re probably seeing some of that play out right now. Conversely, low valuations lead to high future returns. This chart shows the starting P/E ratio of Sensex and the future 5 and 10 year returns. As you can see, low starting valuations tend to result in higher future returns and vice versa. This relationship isn’t ironclad and there are outliers. Having said, it’s a reasonably good heuristic to get a fuzzy sense of where we are in the market cycle and what return to expect. However, if you think you can time the markets based on valuations, you will be sorely disappointed. Like you will be poor disappointed.

Here’s the same chart across multiple time frames. In the short run, markets tend to be random and there’s no strong relationship between valuations and returns. In the long run, however, valuations are like gravity.

Reason 2: Foreign investors are selling like there’s no tomorrow

I’m reliably told by the super-expert folks on Twitter — who seem to be experts on everything from epidemiology, to archaeology, to sociology, to finance — that Indian markets are falling because white people are selling Indian stocks.

After the pandemic, FIIs fell in love with the India growth story. It was a whirlwind romance. They pumped in ₹2.44 lakh crores, DIIs bought ₹10.44 lakh crores, and individuals bought ₹4.55 lakh crores of Indian equities. Everything looked wonderful. The markets peaked in September 2024.

But then, our love story with white people ended in a bitter break-up. After that, foreign institutional investors (FII) sold over Rs 1 lakh crore worth of Indian equities. Meanwhile, domestic institutional investors (DII) have bought over Rs 3.4 lakh crore.

Reason 3: Corporate earnings are weak

Over the last few quarters, the earnings growth of listed companies slowed down dramatically. With such weak earnings, how can Indian stocks justify their lofty earnings?

Here’s the revenue and profit growth of all listed companies. As you can see, there’s been a significant decline in revenue and profit growth over the last few quarters. The last quarter i.e., the December quarter, was marginally better — but nobody knows if revenues, profits and margins will see more sustained growth.

Now, the aggregate numbers can be skewed by some sectors, so here’s a disaggregated view of revenue and profit growth by sector:

Reason 4: The Indian economy is in terrible shape.

Reason 4: The Indian economy is in terrible shape.

India’s GDP growth has moderated. Inflation has taken a toll on Indian households. Urban consumption has fallen off a cliff. Even the government has cut back on spending. Barring the rural economy, most of the Indian economy is in terrible shape. People are not consuming, and companies are not investing.

With all this carnage, “how will the stocks go up?” ask all the experts with “macro-” something in their Twitter bios.

Reason 5: The end is near. We’re 5 minutes away from Rome burning, and Nero has picked up his fiddle.

Since 2020, the proverbial shit has hit the fan so often that the fan is now dark brown, encrusted in dry shit. It started with the pandemic, then Russia invaded Ukraine, then the entire Middle East turned into a Call of Duty trailer, and now we finally have good ol’ Donny speed running America’s civilizational decline. Is this the end of the world?

I’m reliably told by the experts that the end of the world is, on the whole, rather bad for markets.

So, what’s the REAL reason?

Told you: there are more sellers than buyers!

Look, I’m not just messing around. There are only two people who know why the stock market goes up or down: God and a liar. Think of the absurdity of the questions. Every day, millions of people buy and sell stocks. Just like you and I do. To think that one can compress the decisions of millions of market participants into one or two neat reasons is the height of fantasy.

All of that’s fine, but look, I’m scared. What should I do?

See, you probably know whatever I’m about to say. But maybe you need to hear it in a different way. So let’s play a game of I’m going to tell you what you already know with data rangoli.

Breaking news: The stock market has suddenly become risky! Shocking!

As Mahatma Gandhi once said, the returns you make in the stock market are proportional to your ability to resist peeing your pants once the market falls 20%.

(If you think he didn’t say it, prove it!)

Investing is both easy and hard at the same time. Surprising as it may sound, figuring out what to invest in is the easy part. The hard part is holding on to that investment in times like these.

Here’s something counterintuitive: the stock market spends most of its time in a drawdown. For the Nifty 500 that happens 90% of the time. A drawdown happens when the market or an investment is below its previous peak. So, the BSE Sensex spends 90% of its time below the last peak.

What should that tell you? Well, the stock market basically falls all the time.

Of course, most of those falls are fairly small. But bad things happen, and they happen regularly.

Yet, through war, disease, terrorist attacks, political assassinations, scams, Rohit Shetty movies, and other assorted catastrophes, the Indian stock market has steadily gone up. Here’s some proof:

Looking at this graph, it almost feels like bad things are the norm and good things are the exception — but it isn’t. Paradoxically, the fact that we’re so resilient in the face of bad news is the best news of all.

The only certainty in the market is uncertainty!

The legendary Howard Marks said something beautiful that stuck with me:

In the investment business, there’s no place for certainty. And Mark Twain said, it ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for certain that just ain’t true. And so you can have opinions, but you should never be certain that you’re right. And you should never arrange your financial affairs on the assumption that your forecast is right because it can be right intellectually or factually or rationally, but just take a long time to materialize. And if you can’t survive between when you take your position and when your expectation comes true, then obviously it’s not something you should do. And one of my colleagues once wrote a note to his clients, he says, if you name a price, don’t name a date. And if you name a date, don’t name a price.

Think about why you invest in equities in the first place. It’s because they have the highest probability of high returns, right? You want some of that equity action precisely because it’ll probably earn you better returns than a government bond.

But if that’s the case, how can stocks not be risky? Stocks offer higher returns precisely because they are risky. Think of a world where that wasn’t the case. If stocks were not risky, those high returns would be arbitraged away. People would load up on more and more stocks, to a point where it would be foolish to expect returns higher than on a government bond. Sure, valuations would perennially be high — but you wouldn’t find any opportunity to actually make money. Because the return would be so certain, someone with bigger pockets than you would already have bought that opportunity.

If someone offers you low risk and high returns, you’re being scammed.

Volatility is the price of admission in the stock market. Do you want higher returns than a fixed deposit? The price you pay for that is feeling shitty in bad times, like this one. If you don’t want this volatility, then you should have lower equity exposure. All of this is bloody obvious, but it bears reminding, because people keep getting carried away.

Uncertainty isn’t a bug — it’s a feature of the stock market. Get used to it or get out.

20% falls are far more common than you think

As I write this post, the broader Nifty 500 is down about 15-16%.

If that seems scary, then I have news for you: 20% falls are more common than you think. Even in years when the stock market went up, you’re practically guaranteed to see at least one 10%+ fall.

Here are some stats:

- We have about 45 years of Sensex data. Of this, it went up in 35 years (75%) and went down in 12 years (25%).

- The best year was 1991 with 95.88% returns. The worst year was 2008 with -51.61%.

- In all these years, the average drawdown was 20%, and the median drawdown was 16%.

- In 75% of years, investors experienced drawdowns of at least 11%

Can things get worse? Absolutely!

Will they? I am not an astrologer.

What I do know is that Sensex returns have been positive for 9 straight years. If I remember my biology class correctly, trees don’t grow to the sky, and the stock market doesn’t go to the moon. We were bound to see a bad time eventually.

We had only seen good times for a long while. Things were bound to change. Everything in life is cyclical — especially the stock market. Good times are always followed by bad times and vice versa. If you only want to see good times, the stock market is the wrong place. You’re better off researching psychedelic substances.

Luck of the random

In any given year, the stock market behaves like a drunk man finding his way home in the dark. That is to say, it’s all over the place — it’s random. You just have to get used to it.

Check out the annual returns of the Sensex, for instance:

There’s no obvious pattern in the data. However, if you fit a trendline through it, it slopes downward — indicating declining returns over time. You can see this in the size of the return circles as well.

In a loose sense, this randomness is a feature, not a bug. If the stock market was predictable, everyone would invest. And the more that money entered the market, the lower your future expected returns would go. Many people can’t stomach the randomness of the stock market, preferring certainty. That is where your opportunity lies. Weak hands panic, sell equities and give up the equity premium. Strong hands earn it.

If you are young, be happy.

The great William Bernstein once said, “If you are young, you need to get on your knees and pray for a bear market.” This stuck with me because it’s so true.

Host: From Rational Expectations, you said something along the lines of young investors should be praying for long extended bear markets.

William Bernstein: Yeah, of course. And that gets to radical issue called return sequence, which is that if you are in an accumulation phase of your investing career, you’re saving periodically, then you should get down on your knees and pray, as I wrote, for awful returns, awful bear markets, great volatility, so you can accumulate shares at low prices. On the other hand, if you were a geezer like me, you don’t want to see bad returns right off the bat, you want to see good returns right off the bat. So you can build up your nest egg a little more for so when the bad times come, you’ve got plenty of cushions. So how risky stocks are depends more on where in your investing lifecycle you are. If you have more human capital, that investment capital, you want bad returns and the opposite is true.

When the markets fall sharply, so do valuations. And that means the future expected returns go up. If you’re young, you shouldn’t be afraid of a bear market, but happy. The entire stock market is on a clearance sale! When valuations are low, you are, in essence, paying less for every rupee of a company’s earnings — which is ultimately what you’re investing in. You’re buying the same tiny piece of a company either way, but in a bear market, you get a nice discount.

The opposite applies as well. If you buy things at ridiculous valuations, your future expected returns tend to be low. Over the long term, there is a significant statistical relationship between starting valuations and future expected returns. Low valuations mean the odds of future returns are higher, and vice versa.

Be careful, though: you can’t time markets based on valuations. In fact, of all the ways you can time markets, valuations tend to be the worst. Stocks can stay overvalued, or undervalued, for long periods of time.

The only thing valuations are good for is helping you get a sense of the returns you can hope for, going forward. This lets you tweak your asset allocation to a degree, but it doesn’t mean you can take all-or-nothing calls with valuations.

Know what to worry about

You think losing 15% hurts?

If your answer is “yes”, you clearly have no clue about how bad things can get. Here’s one chart that’s forever etched into my brain — where Bridgwater lists the worst market crashes in history. This is beyond depressing; I don’t know enough English to describe this.

Indian investors have been blessed with good returns for a long term. We’ve never seen market phases where returns have been negative for decades. Here’s some data from a post I wrote last year with some gyan on how to prepare for a bear market:

-

- From 1929 to 1943, the S&P 500 underperformed 3-month T-bills for 15 years.

- From 1966 to 1982, the S&P 500 underperformed 3-month T-bills again for 17 years, although the margin was close.

- From 2000 to 2012, the S&P 500 underperformed both 3-month T-bills and the 10-year Treasury bond.

That’s rough.

Here are worst market phases we have seen in India:

All in all, we’ve been really lucky. We haven’t really had a lot of terrible crashes, and even when we have, things have resolved themselves. Don’t set your expectations on how India’s stock markets have behaved so far. Base it on how stock markets behave in general.

Your real worry should be how to prepare for the sort of terrible decade-long grinds that so much of the world has seen, not a mere dip like the one we have now.

Diversification is insurance against arrogance and ignorance.

I like showing this chart, because I can explain multiple things with just one chart.

- Equities are volatile, and I mean, really volatile. Duh!

- Asset classes — even ‘safe’ ones — can go through long periods of underperformance. Look at gold returns from 2013 to 2018. That would’ve been painful.

- The best solution to deal with 1 and 2 is to diversify. I’ve created three simple portfolios to show how diversification helps.

Even simple diversification and asset allocation can lead to good outcomes. But how should you divide your investments across asset classes? That’s one of the trickiest questions in finance. There are too many assumptions, and so many factors you need to consider.

There are countless strategies you can use to allocate assets. They sound fancy as hell: mean variance optimization, capital asset pricing, risk parity, tactical asset allocation, goals-based investing, lifecycle approaches. However, I doubt that most investors have the ability or patience for any of this. That’s why I’m a huge fan of simple rules of thumb. This is a heretical thing to say for a lot of finance experts. To which I say: damn them and their prissy sensibilities!

Scroll up a little and look at the last column. There, I’ve calculated equal-weight returns across all three assets. That is 33% each in equity, debt, and gold. It’s so basic, you’d laugh at it if a friend suggested it to you. But the portfolio has done pretty well, hasn’t it? Even if you were to just do this much without creating fancy efficient frontier curves, you’d have come out alright.

Now, you might ask me: Is this naive diversification the “best” way to allocate assets?

To which I’d answer, define “best”.

Look, I’m not just trying to be annoying. For the most part, the ‘best’ asset class, the ‘best’ strategy, and the ‘best’ allocation all depend on what’s happening in the market at that very moment. And that can only be known in hindsight. Your job as an investor is not to seek the “best” in everything. Not only is that a waste of your time — it’s also a path to guaranteed misery. You need to be good enough when it comes to investing, at least when starting out.

A dumb equal-weight portfolio is not a bad idea to start with. But don’t worry too much — as long as you have reasonable allocation to various risk assets, i.e., equity, debt, gold, real estate, etc., and are patient, the probabilities of you doing well are high. You might argue with me: maybe my chart is stupid. 2005 is too short a time to judge equal-weight portfolio performance, after all. Fair enough: here’s data that goes back to the 1990.

Having said that, ultimately, your asset allocation should depend on what you want from life. It should be a mirror image of your goals, life circumstances, and your temperance. It should reflect those attributes and evolve with time.

The point of diversification isn’t to generate the highest returns — it is to reduce unhappiness. By spreading your money between different asset classes, you are necessarily reducing your returns but your risk as well. Diversification moves you from the extremes to a reasonable middle path, and that’s a good thing.

Simple works…eventually!

There’s nothing new in markets. This applies to both — what happens in the markets, and the nonsense that people say.

Over the last couple of months, there was a pointless debate raging on Twitter, about SIPs being ‘sub-optimal’. I don’t get it. People who’ve worked in finance for decades don’t seem to understand what an SIP is and what it’s used for!

Let’s get a few things straight:

- SIPs are not a ‘strategy’. SIP is just a way of investing money regularly. Calling an SIP a ‘strategy’ is calling walking “a strategy to go from point X to Y”.

- SIPs are neither good nor bad. They’re just a way to put money into something. The real question to ask is: where does the SIP money go, and how are those assets allocated?

- Finally, the SIP vs. lumpsum debate. In most cases, lumpsum does better than an SIP [1, 2]. Cooool… but there’s a slight problem: most people don’t have lumpsumps lying around? Most individual investors tend to have a job. They get a monthly salary, save a part of it and invest in mutual funds. How else do they invest if not for an SIP?

Look, patience and discipline pay-off in the long run. That’s all you really need to know.

Frankly, this whole debate is so pointless that I didn’t even bother running any numbers. The AMCs had done my job. Here are few more charts:

Source: Motilal Oswal

Source: White Oak MF

Source: White Oak MF

Historical data suggests that the SIP, which has delivered comparatively lower returns in the initial 5 years, has delivered a better return on 10 years basis (on an average).

Risk management is not free

Whenever the markets fall, “risk management” becomes a hot topic. But before we talk about how to manage risk, you need to know a few things:

- If you want higher returns, then you need to take some risk. Shocking, right?

- You cannot diversify away all your risk. If you do, you’ll get the returns of a fixed deposit.

- So, you must choose the risks you want to take. As Corey Hoffstein put it succinctly, “no pain, no premium.” If you buy an equity fund, you are trying to harvest the equity risk premium. If you buy factor funds, like value, quality, momentum, etc., you are trying to harvest those factor premiums.

- Beware of uncompensated risk. You have to take risks if you’re looking for returns, but the opposite isn’t true.

While you can diversify across asset classes, you can also diversify across risks. When you put together a portfolio of assets, you’re basically assembling a stream of risks.

If those risks are chosen well, they’ll probably be compensated well. Let’s say, for example, you are investing in the Nifty LargeMid 250 index fund. You are, more or less, taking on a little bit of the entire market risk. You’ll probably earn a higher return than a government bond, but that’s because equities are volatile. They regularly fall 10-15%. On bad occasions like 2008, they fall by 60%. Not everybody can stay invested through such bad times, and those who do earn a premium. The weak hands compensate the strong hands.

On the other hand, you could buy a random portfolio of penny stocks and other terrible stocks. You’re at risk, but this is uncompensated risk. I mean, why should you be compensated for buying shit stocks?

You need to know what risks you’re taking, what the compensation for bearing that risk is, and if the compensation is enough. As obvious as this sounds, most investors don’t think this way.

Which brings me to risk management: it’s not free. There are plenty of ways you can cut your risk — from rudimentary moving average strategies to hedging your investments with futures and options, etc. But these come at a cost: lower returns.

Many retail investors have this fantasy: with the right risk management strategy, they could have it all — high returns and less risk. This notion is just that — a fantasy. To reiterate, if you’re getting Nifty-like returns with half the risk, you’re in the process of being scammed. If you want less risk, you will have to sacrifice returns. You have to be OK with underperforming a dumb strategy like buy-and-hold.

Having said that, I like keeping things simple. I think the only risk management strategy that most individual investors need are diversification, sensible asset allocation, and the ability to withstand pain. To be a good investor, you need good core strength and glute strength — because you’ll constantly feel like clenching your gut and butt.

Even foresight can’t save you from risk

Let me go back to the point I made about uncertainty earlier iin the post. At a philosophical level, you’re earning a premium on an asset class because you’re accepting the inherent uncertainty of the future. Now, imagine, for a minute, that you knew what’s going to happen tomorrow well in advance. Do you think you could make money in that world? Well, here’s why you should be less sure.

Victor Haghani of LTCM fame ran a study with students studying finance and business administration. He gave them $50 and a copy of The Wall Street Journal one day in advance. They could see all the news they needed, other than the next day’s stock and bond prices. Based on that news, the participants could trade the S&P 500 index and 30-year US Treasury bonds.

You’d assume that given people had a clear idea of what was going to happen the next day, they would make money. Wrong. About half the participants lost money. One out of 6 people went bust. The reasons why people lost money were telling:

The players in the proctored experiment did not do very well, despite having the front page of the newspaper 36 hours ahead of time. About half of them lost money, and one in six actually went bust. The average payout was just $51.62 (a gain of just 3.2%), which is statistically indistinguishable from breaking even. The poor results were a product of: 1) not guessing the direction of stocks and bonds very well, and 2) poor trade-sizing. The players guessed the direction of stocks and bonds correctly on just 51.5% of the roughly 2,000 trades they made. They guessed the direction of bonds correctly 56% of the time, but bet less of their capital on bonds than on stocks (if you’re planning a career as a proprietary macro trader, consider putting your focus on bonds).

One of my all-time favorite articles is called “Even God would get fired as an Active Investor.” It’s a simple thought experiment that shows why investing is difficult.

Let’s say you’re God. You always know the best performing stocks of the next 5 years. You could easily kick ass and earn more than 30% annualized. You’d be the greatest investor ever, right?

Well, no. If you constantly bet on the best-performing stocks of the next five years, you’d see some terrible drawdowns on the way. You’d live through the Great Depression crash — where stocks fell 76% — and multiple other 20-40% falls. There would be many times in between where passive funds would easily beat your returns. Every time that happened, you’d have to explain yourself to panicking investors. Ultimately, God would probably be fired from the cosmically perfect hedge fund.

Here’s the upshot: don’t waste your time trying to second guess the future. Many people have lost fortunes that way. Trite as might sound, the ability to just sit and do nothing in the markets is a superpower and an edge. To me, this is probably the last remaining edge.

What you can do, though, is to better understand what you don’t know.

Shape of your ignorance

One of the best things I’ve read so far this year is this wonderful article by Eric Schwitzgebel, who teaches philosophy at the University of California. The article is a celebration of the unique and wonderful human ability to ask questions. He says that asking “why?” is the real essence of philosophy. To ask “why” makes us all philosophers. When we ask questions, we are pushing the boundaries of what we know and discover deeper meaning and even deeper questions.

I love this article because of this utterly awesome passage:

This isn’t to say that philosophical enquiry should be unconstrained by concern for discovering truths. On the contrary, we should pursue truth earnestly. But philosophical enquiry is naturally adventuresome, exploring topics where our ordinary epistemic tools break, revealing their limitations. When we plunge after the most fundamental questions, we shouldn’t expect to find the one final truth that all future thinkers will be compelled to accept by argumentative force. More realistically, we should hope for glimpses through the fog. Often, our best success is only to better appreciate the shape of our ignorance. The distinctively awesome task of philosophy is to contemplate the most general and important questions that lie beyond our full grasp.

“Shape of our ignorance”. What a profoundly beautiful framing! I’ve been unable to stop thinking about this line ever since I read it. It’s tattooed onto my brain.

Knowing the shape of our ignorance is crucial for a successful investor. Once you step back and think about it, investing is a leap of faith. To invest is to make a hopeful bet that the companies we choose will grow, generate profits, and reward us. It’s a hopeful bet that the 100s of things that can go wrong won’t.

To invest is to accept the fact that the future is unknowable. It’s to make peace with the fact that there’s only so much in our control. This is hard for us humans — the thing we crave the most is certainty. Remember, we are creatures that choose certain pain over uncertain pain

We need to fight this part of our programming. Given how we investors have to embark on long walks in the whirlpool of uncertainty that is the stock market, it’s crucial to know what we don’t know. Investing success depends on avoiding stupidity rather than seeking brilliance. It comes from a faithful effort to understand the fundamentals, a realistic assessment of one’s temperament and the equanimity to know that there will always be things we don’t know. Investing disasters, on the other hand, lie in between the things that investors think they know and things they actually know.

This is why you need to know the shape of your ignorance.

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.” ― Mark Twain

Words from the wise Jack Bogle

Jack Bogle is the founder of the asset management behemoth, Vanguard. He was a true investing pioneer who created the first retail index fund.

He was also a remarkable human. The investing world isn’t a place where it’s easy to find heroes to look up to. Of the handful of people you can look up to, Jack is right at the top. He’s long been my personal hero. A lot of things I’ve learned about investing, money and life have been from him. Sadly, he’s no longer with us.

Whenever the markets start wobbling, he’s the first person I think of. So I recently went back and read this phenomenally great interview he gave in 2015. I want you to see this passage, which captures everything an individual investor needs to know to succeed in the jungle that’s the stock market:

So, what is the best approach to investment success? In my opinion, less choice. Low cost. Don’t look at your portfolio values very frequently. Don’t peek! It’s a bit hyperbolic, but I tell people that every time they get a statement, throw it in the waste basket. Do not look at it. And only when you retire, open the statement.

But before you open it, have a cardiologist in the room, because you’re probably going to have a heart attack. You simply won’t believe how much money you’ve accumulated over all those years. It’s the compounding. The phrase I use is this: “Enjoy the magic of compounding long-term investment returns without the tyranny of compounding long-term costs.” It goes back to what I suggested earlier, the index guarantee is that you will have the same non-manager when you retire as you did when you started investing 50 years, 60 years earlier.

I’ll leave you with his 10 simple rules for investing success. If you internalize them stick to them like grim that, you are all but guaranteed to build wealth:

-

- Remember Reversion to the Mean

- Time Is Your Friend, Impulse Is Your Enemy

- Buy Right and Hold Tight

- Have Realistic Expectations: The Bagel and the Doughnut

- Forget the Needle, Buy the Haystack

- Minimize the Croupier’s Take

- There’s No Escaping Risk

- Beware of Fighting the Last War

- The Hedgehog Bests the Fox

- Stay the Course

The secret to investing is that there is no secret. When you consider the previous nine rules, you realize what they are not about. They are not about magic or legerdemain, nor about forecasting the unforecastable, nor about betting against long and ultimately insurmountable odds, nor about learning some great secret of successful investing. For there is no great secret. There is only the majesty of simplicity. These rules are about elementary arithmetic, about fundamental and unarguable principles. Yes, investing is simple. But it is not easy, for it requires discipline, patience, steadfastness, and that most uncommon of all gifts, common sense.

When you own the entire stock market through a broad stock index fund, all the while balancing your portfolio with an appropriate allocation to an all-bond-market index fund, you create the optimal investment strategy. While it is not necessarily the best strategy (as I conceded at the beginning of this chapter), the number of strategies that are worse is infinite. Owning index funds, with their cost-efficiency, their tax-efficiency, and their assurance that you will earn your fair share of the markets’ returns, is, by definition a winning strategy. As the financial markets swing back and forth, do your best to ignore the momentary cacophony, and to separate the transitory from the durable. This discipline is best summed up by the most important principle of all investment wisdom: Stay the course!

So, what do you think?

One of the most beautiful articles on markets, I have ever read, anywhere.

Lot of data, analysis, thoughtfulness, and market wisdom!

A very good article. But for investors, it is not the best of times. They should either sit ”tight” ( to what extent!) or try to minimize the losses. For traders it is paradise to use the volatility and Fibonacci retracement on a daily or once in 2/3 days basis . making good gains in F&O holding positions for a day or two only.

Happy trading and not investing since no one knows whether it is bottomed out.

Loved this article. This is just WOW!!!!! Keep writing would love to read more of your work. 🙂

Great read. This should be taught in schools as part of personal finance.

This is one of the best reads in my recent times, Hats off for the quality of research and time and depth you took us through.

Im really hoping to learning from your wisdom more, Keep sharing you wealth of knowledge, Im really grateful for finding this gem.

This article is a very valuable collection of Data. However I feel to go through the article & analyze will be difficult task. Make the article precise & inference should be emphatic based on earlier given logic. Your inference here about asset allocation & Index investing is very relevant ,appropriate. However in asset allocation real estate is to added.

Thanks

Wow!!! This is not an investment article ..this is a deep Investment psychology of the author and many others.Articulated wonderfully in data and text ,making it so engrossing and I must say a valuable read.

Commendable job and I really hope that more and more investors get to read this content.

Excellent job Bhuvan..hoping to read and learn more from you!!

This one is a gem! Thanks.

Great read.

Captivating writing, thanks for sharing your wisdom

Wow ! Amazing stuff ! Bas ab paisa chahiye ye itna gyaan apply karne ke liye !

Excellent post. Certainly well researched, but more importantly well written. Never loses the context and the message it tries to convey. Please keep up with the good work. Hopefully, the post gets a wider dissemination. The figure ”Journey of Sensex” and the final apt message ”Stay the Course” pretty much sums it up.

I like this article❤️

Wonderful and eloquent. Made so many concepts clear. Will definitely recommend this article to all my friends ,peers,investors.

Very well researched and it surely conveyed what it intended to. Thank you author and zerodha fir educative initiatives such as these.

This article should be taught in B Schools. So well researched

Insightful !!

Way of delivery with charts, humour and sarcasm is apt.

Great work.

Cruel understanding of the market in a perfect sense

Great Bhuvan

You deserve a raise!

Thanks for sharing such valuable information..

I am feeling much better after reading your article.

This is perhaps the best MBA course wrapped in an article: Here We Go Again—a true masterclass. I will preserve this and might even take a hard copy to pass on to my kids. Thanks a lot!

Well, a much needed console was given with this post. Thanks for this insightful piece of information!

Sarcasm surely helps feel better 🥲😅

There is so much wisdom here. Well written.

I think good graphics and best information thank you 🙏

Writer got humour

Excellent article Bhuvan !!!

Gem of a piece !

Great one Bhuvan✍️, the way you write and compile all the graphs , quotes is quite commendable! Keep uploading more.