The dramatic transformation of the Indian stock market

Five years ago, a horrendous virus called COVID-19 made an unwelcome entry into our lives. It eventually became a weak shadow of itself. We barely even think of it anymore. But in its short stint, it changed our world forever. If the virus had never come our way, the changes of these five years would probably have taken decades to play out.

Nowhere is this more apparent than the Indian stock market. Most people don’t appreciate this fact enough. But when you look at the numbers, you see two different realities: the world before COVID, and the world after.

Why write this post now?

Well, for one, I’ve wanted to write this for a long time, but I got lazy. Sorry. But more importantly, I think this wild moment in time might be reaching its climax.

After five years of relentless growth, the markets seem to be taking a breather. Market activity peaked across the board sometime around September 2024, and it’s been falling ever since. We wrote about this recently. But market activity is recursive. The better markets perform, the more activity they see. If the performance of our markets has really slipped, where they go now is anybody’s guess.

So what happened over these five years? Why were they so unusual? And have they changed our markets forever?

Well, for that, let’s look back at these five years and chart out this crazy period.

A long period of calm

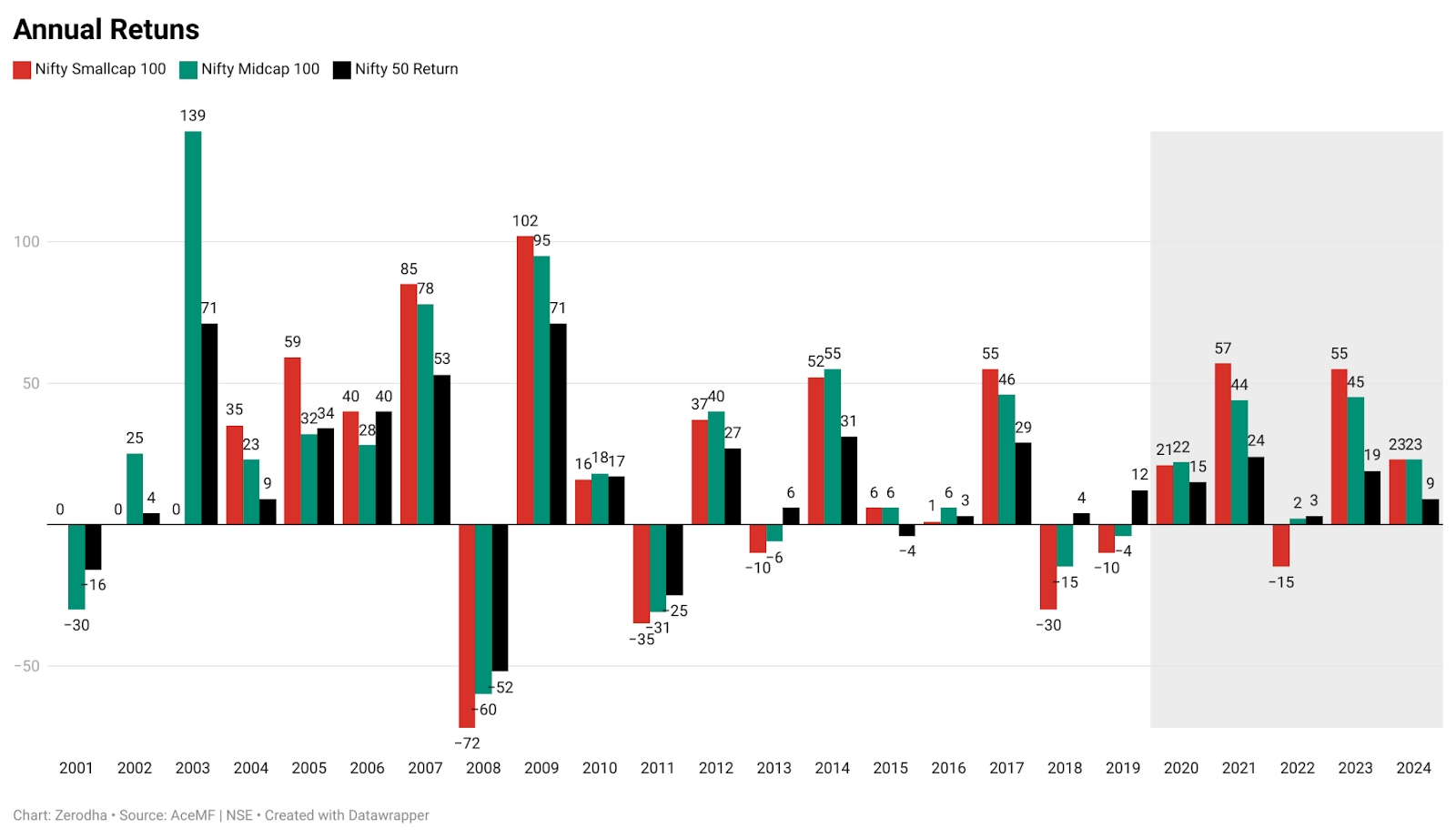

Here are the calendar year returns of the NSE’s large-, mid-, and smallcap indices since inception:

Now, this is a rather small sample size. Nifty 50 starts from 1990. The Nifty Midcap 100 index only starts from 2003. This is too short a time to give you a full picture of Indian market cycles.

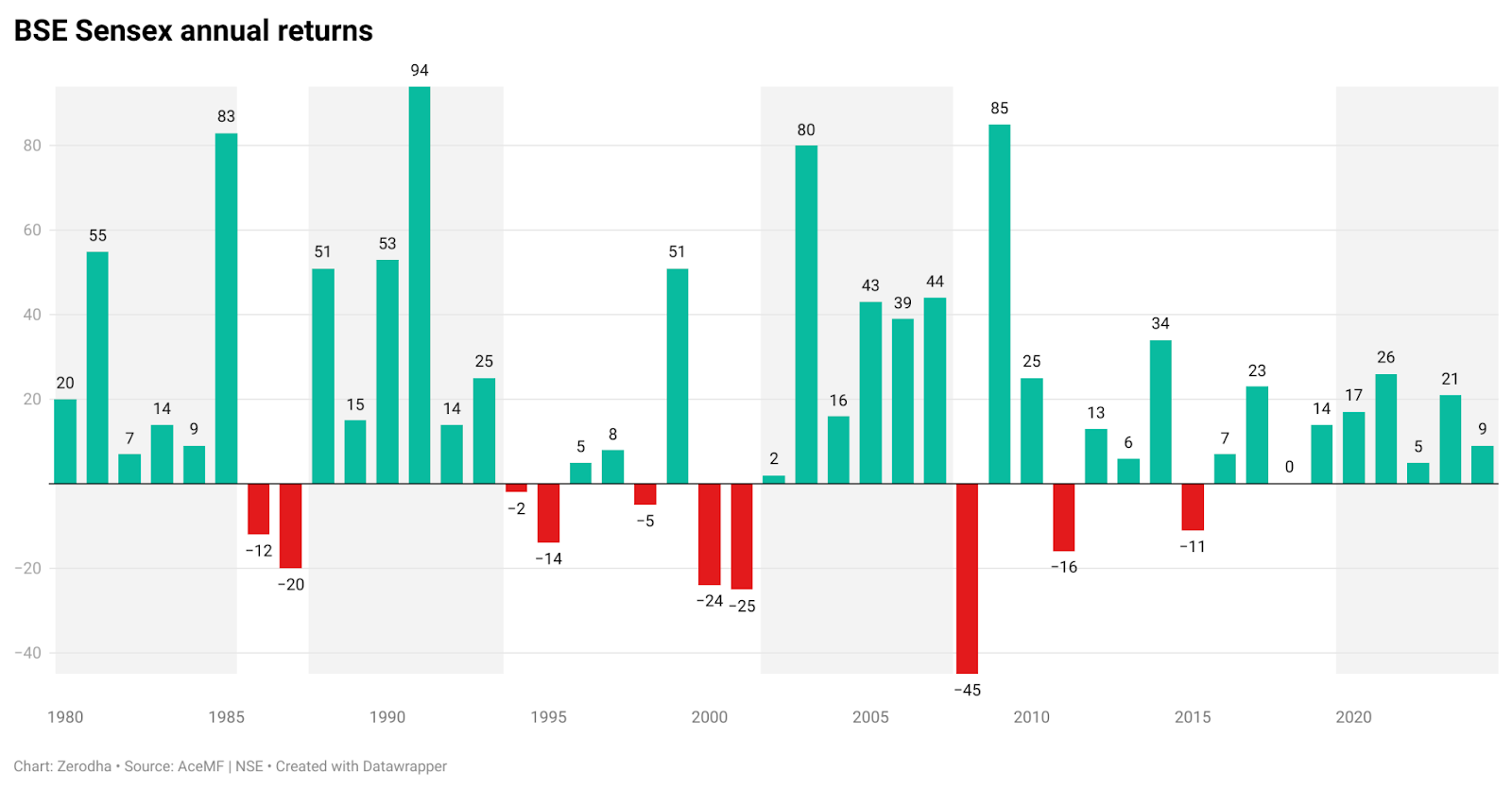

The base year of the BSE Sensex, however, is 1980. That’s a 45-year span, and that should give you a much better picture of the entire(-ish) history of our stock markets.

What you’ll probably notice is that, right now, the good times have lasted for unusually long.

There have been times when the percentage return was better than it is today. If you were investing in 1988-1993 or 2002-2007, your returns would be far wilder. The magnitude of returns has trended lower over time. So, sure, this isn’t the craziest time we’ve seen.

But some of that is just a function of how our markets are much bigger than they once were. Even big movements, today, look tiny in percentage terms.

More importantly, we haven’t seen a big fall in nearly a decade — and that’s a decade which saw a once-in-a-century pandemic and tensions between most of the world’s great powers.

Market activity

There’s another thing that makes the post-COVID market different from previous highs: the stock market has truly become mainstream.

We don’t have enough data to pinpoint why, but let’s be real: all the previous bull runs came in an era when the markets were still analog. Until 2017, everything from opening an account to applying for IPOs involved paperwork. If you were in the markets, you had taken on a massive headache to be there.

That’s not the case now. By the time COVID hit, Indians had smartphones and cheap data, and everything in the markets was digital. When the pandemic hit, all of this clicked together. There was suddenly a spectacular explosion in stock market activity and participation.

Let me share some charts.

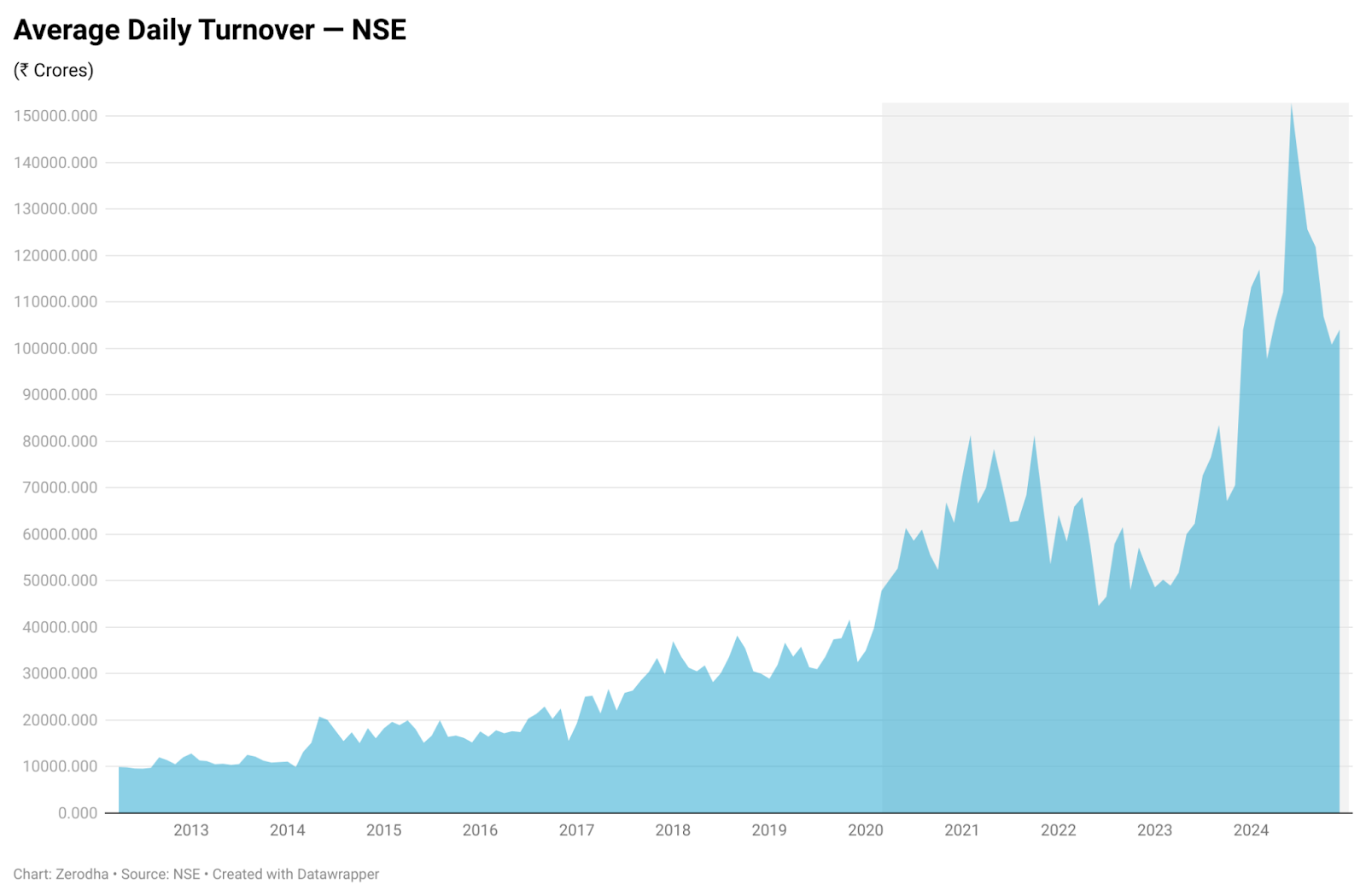

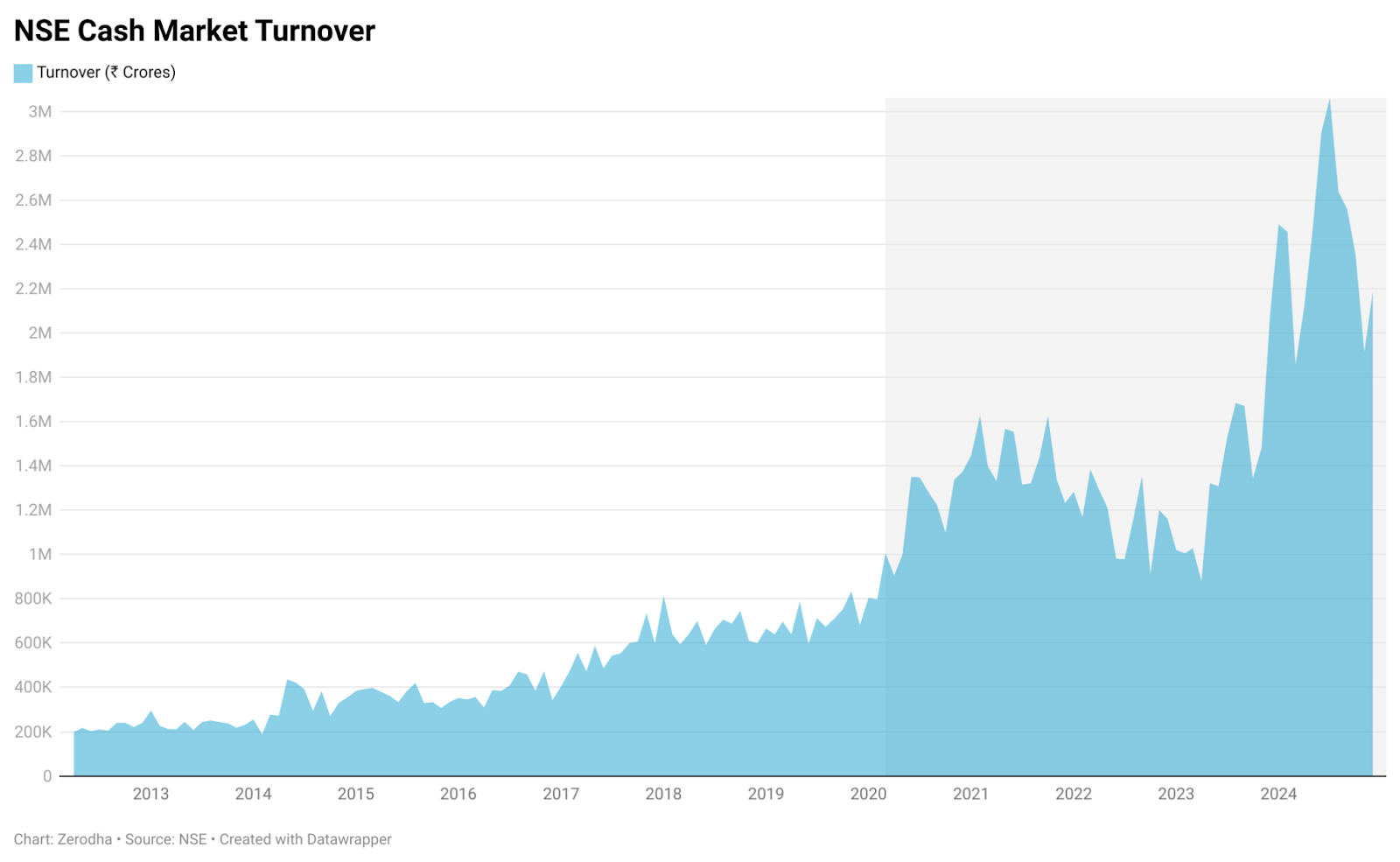

First, the big picture. Here’s the turnover in the cash market segment, or direct equities:

Here’s the average daily turnover. It was around ~Rs. 48,000 crores in March 2020. By December 2024, that had zoomed up all the way to over Rs. 104,000 crores.

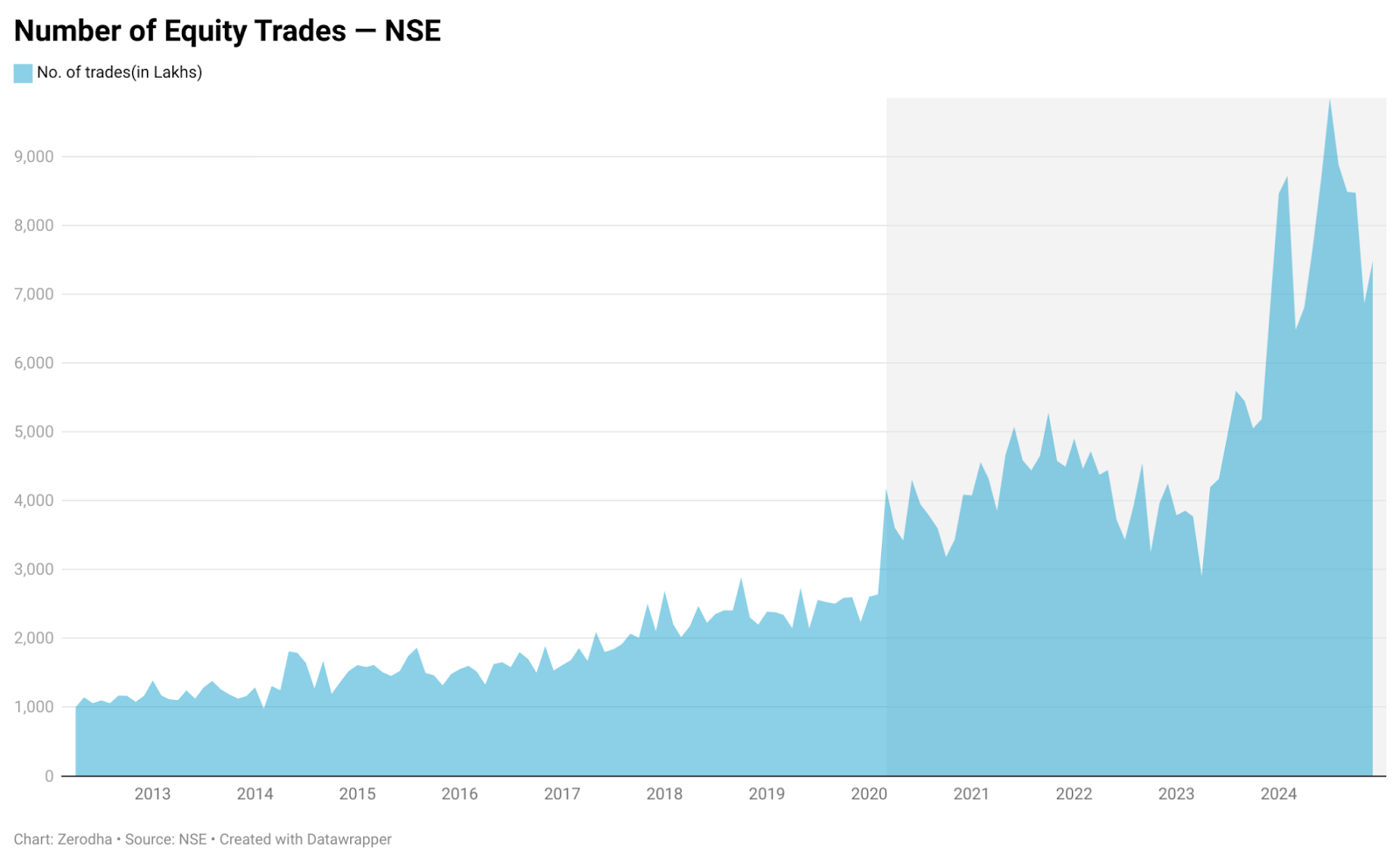

Here’s the number of trades on NSE.

In January 2022, there were 26 crore equity trades on NSE. By December 2024, that had grown to 74 crores — falling from a peak of 98 crore trades in July 2024.

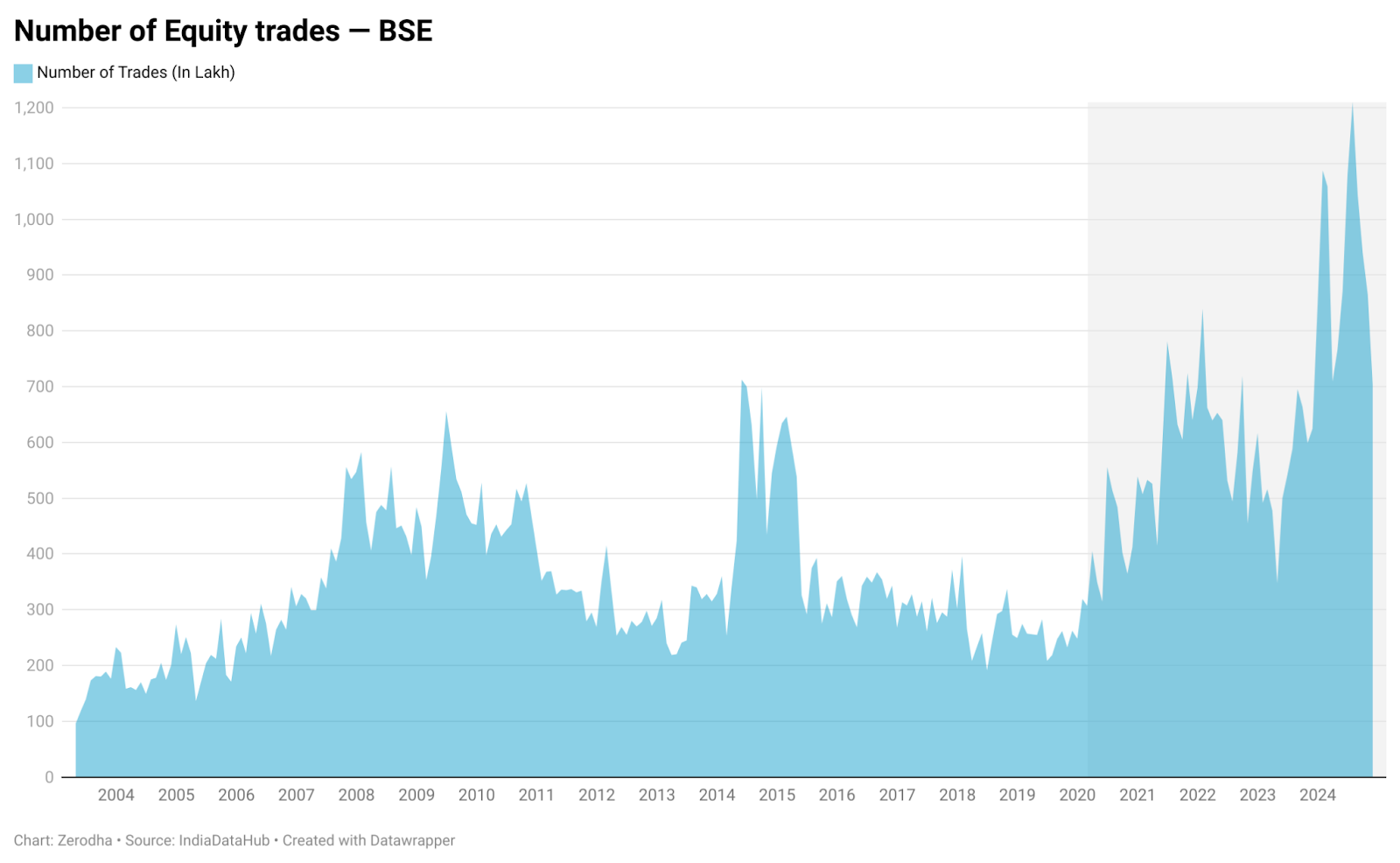

Now, NSE only publishes data from 2012. Thankfully, BSE publishes data for a longer period.

Here’s the trend: between 2003 to 2020, the number of equity trades were basically in the same range — spiking here and there. And then, there was a break-out in 2020. Trading has been elevated ever since.

You can safely assume things would be similar for the NSE — only, with far more trades.

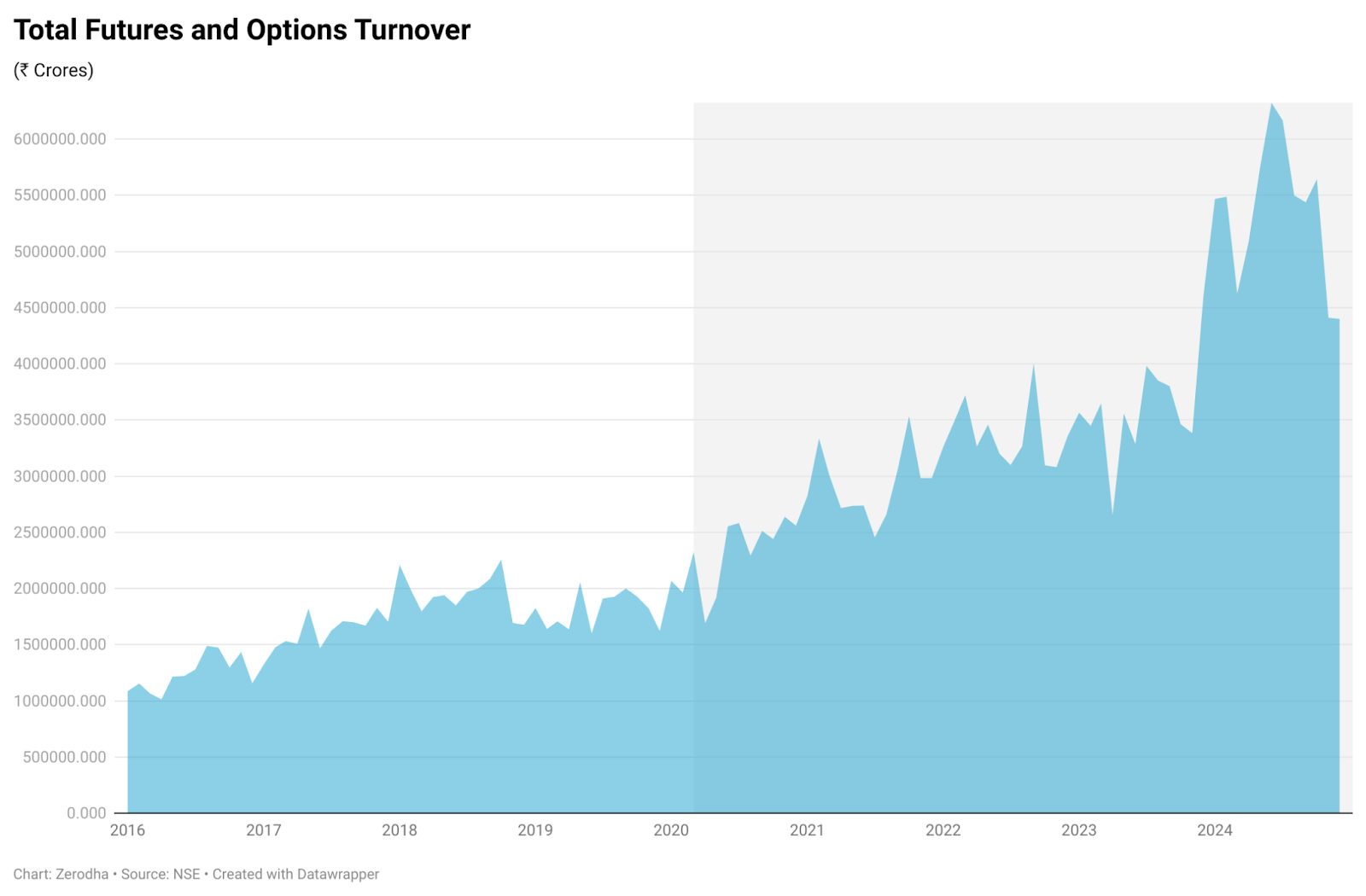

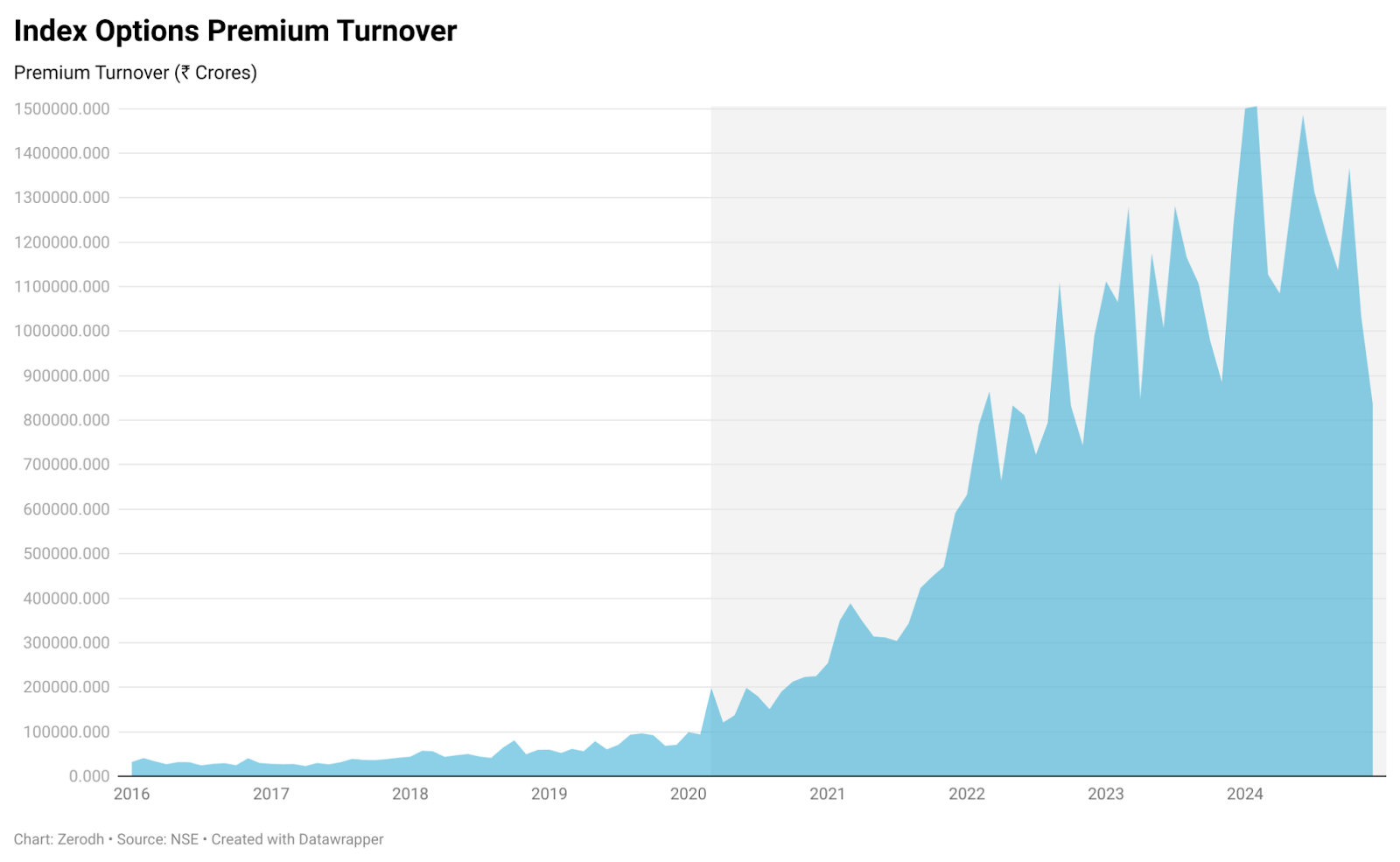

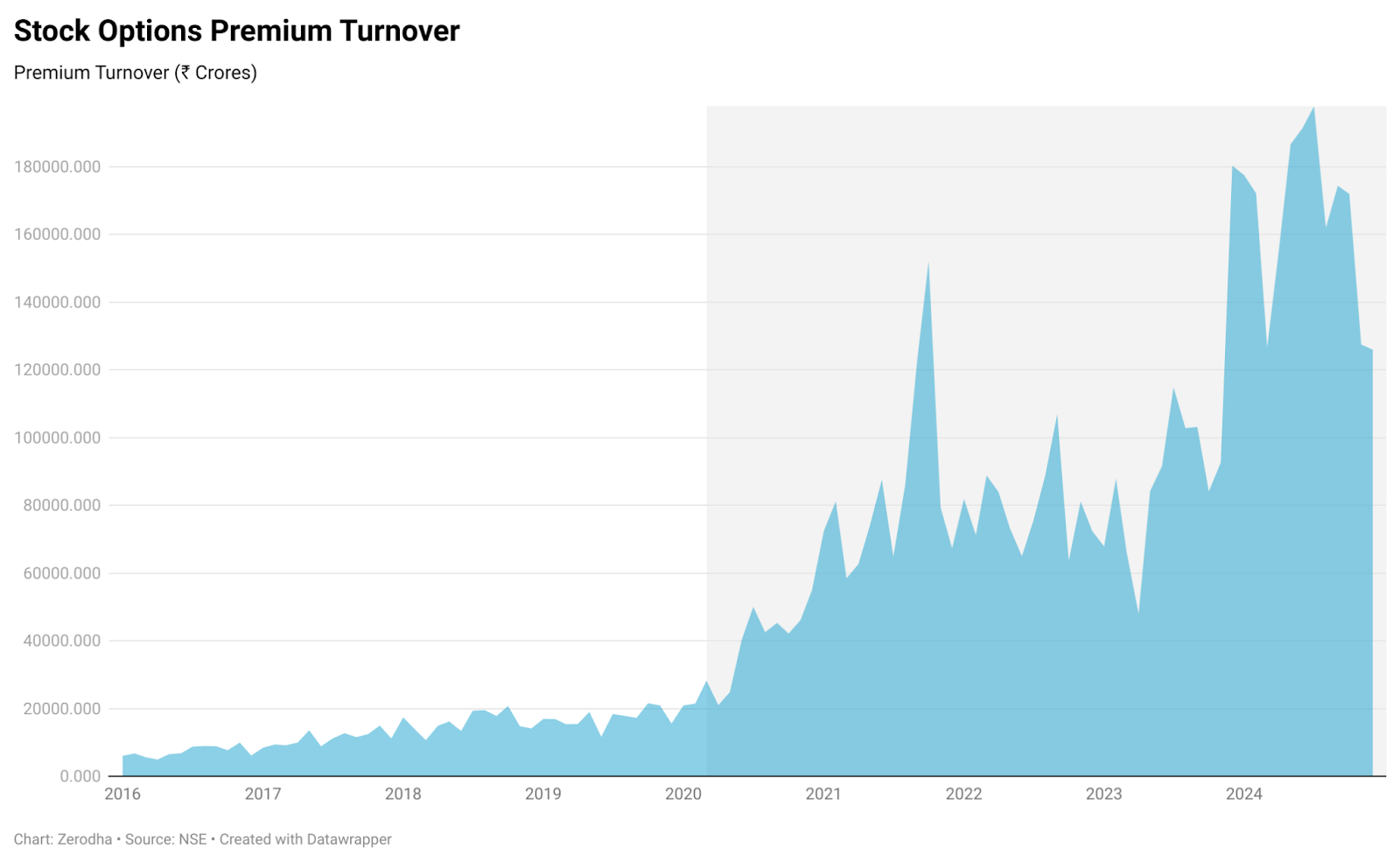

Of course, you can’t really talk about the post-COVID Indian markets without acknowledging the elephant in the room: futures and options (F&O). Over these five years, we’ve seen a spectacular display of speculative mania in much of the F&O segment — most notably options.

Here’s what’s been up with index options:

And here is the turnover in stock options:

Now, index and stock futures didn’t see the same level of crazy. Maybe because you have to pay more STT for futures, compared to options.

I didn’t bother adding a stock futures chart. But index futures do seem a little elevated in the last few years.

Expansion of the market

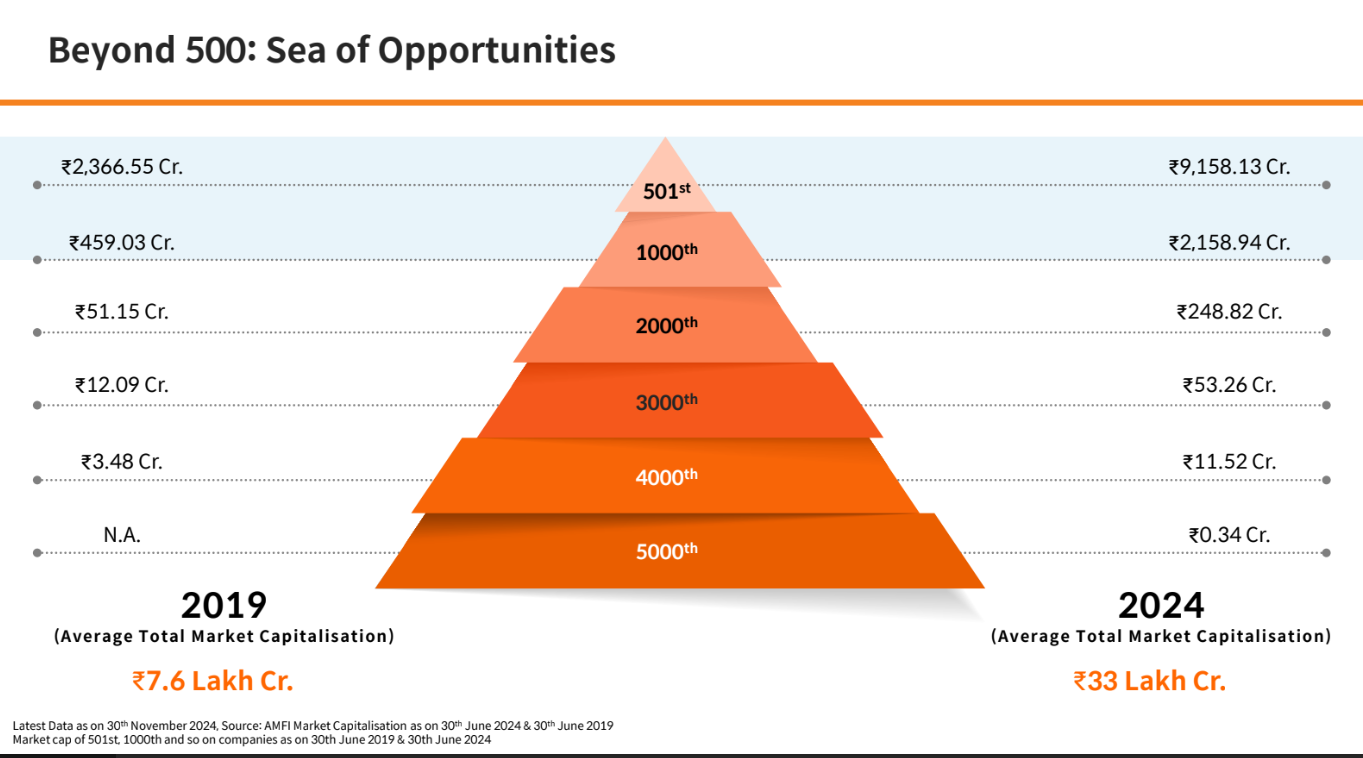

For the longest time, everyone from SEBI, to traders, to fund managers, to all sorts of other large allocators complained about the lack of liquidity in the Indian markets. And they were right. Even as recently as 2018-19, liquidity quickly vanished when you looked beyond the top 100 companies.

But after 2020, this has changed for the better. All market segments aren’t fully liquid, still, but compared to the pre-COVID baseline, things have improved substantially.

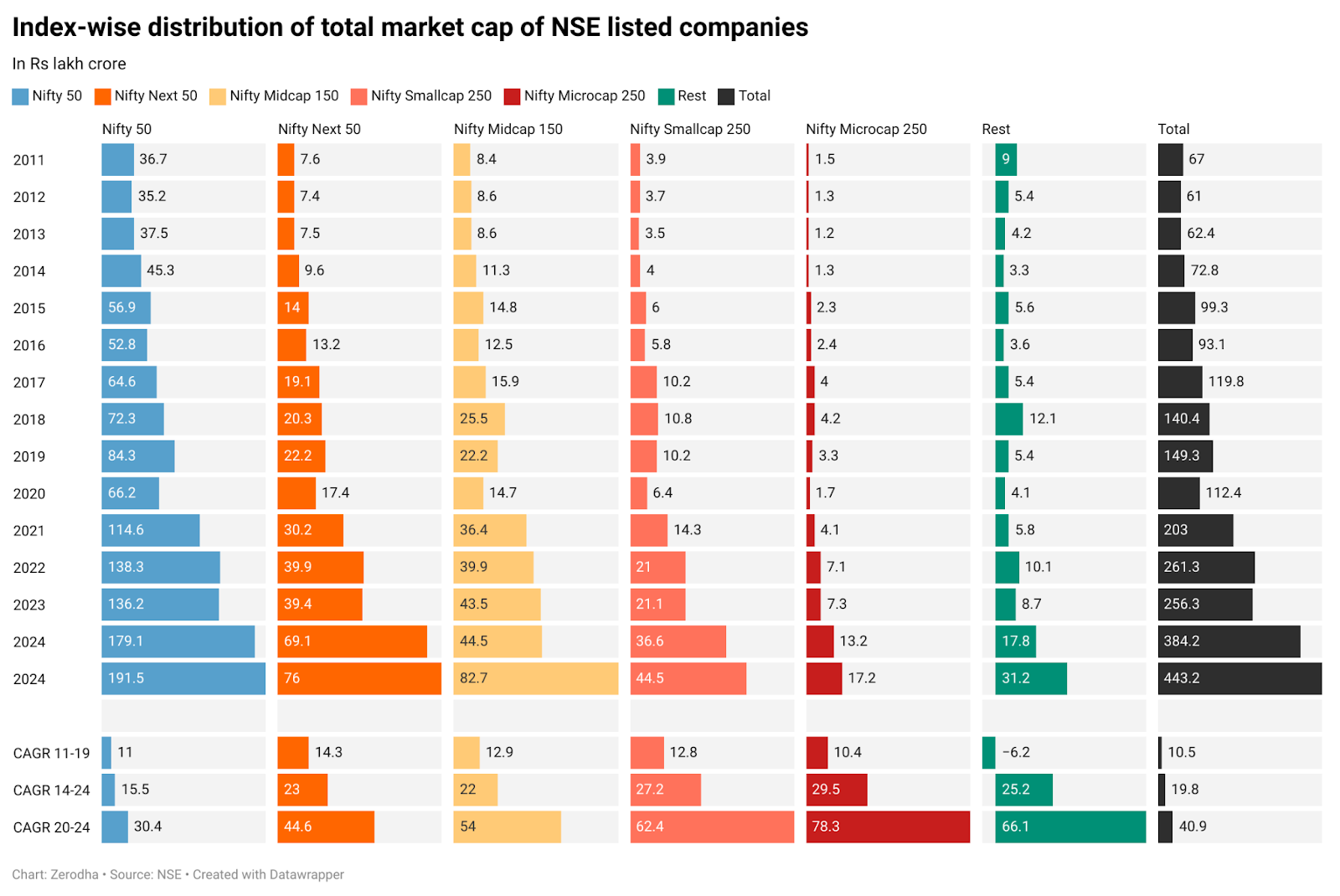

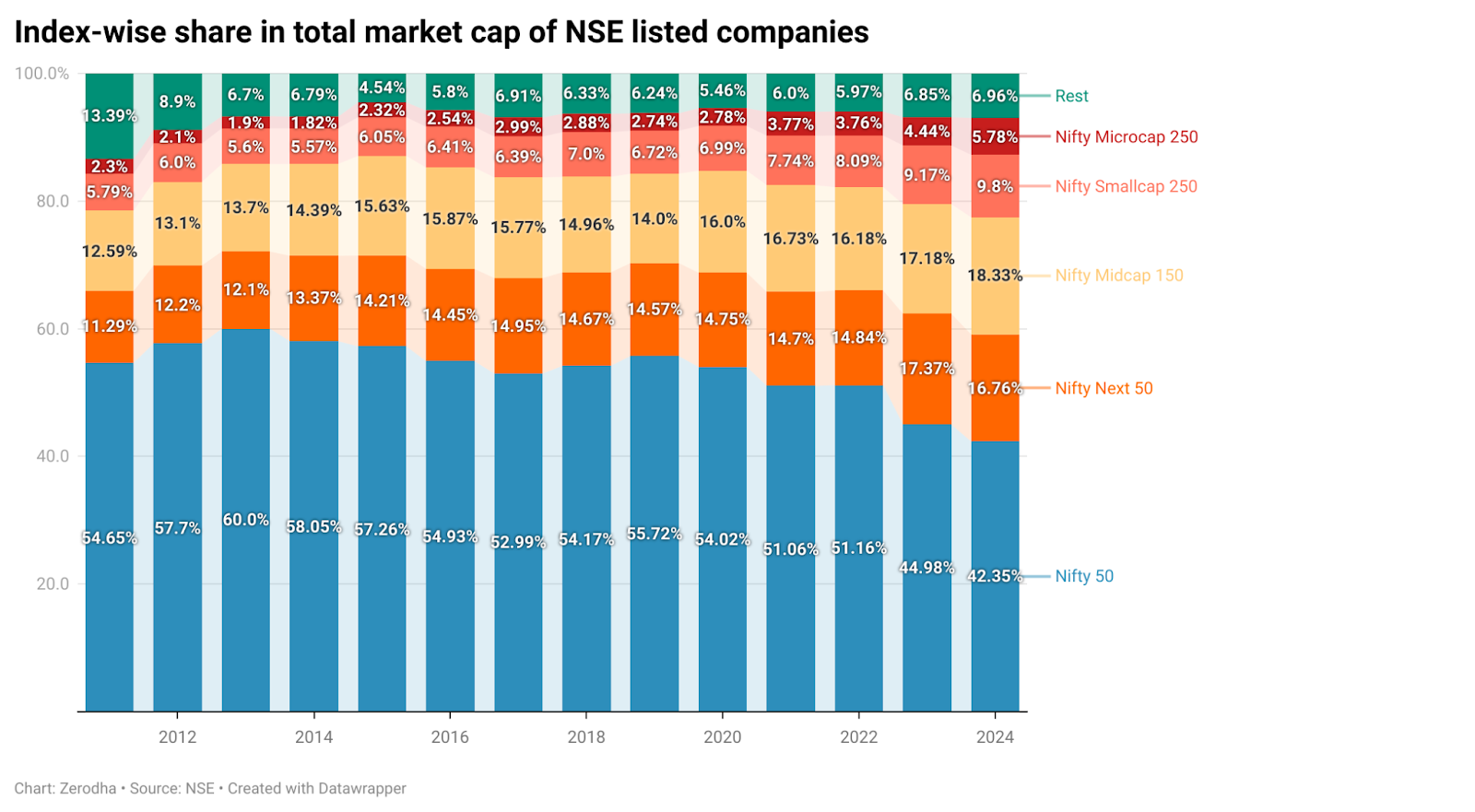

There’s also been a substantial increase in the market of mid-, small-, and micro-caps. That isn’t a perfect indicator of market liquidity, but it’s a decent quick-and-dirty proxy of how people are willing to trade in the scrip of more and more companies.

Or look at how the average market capitalisation of companies has shot up across different market segments.

There are many more ways to think about how our markets have expanded. One I like is to look at how many different securities were traded over time.

See, there are almost 5,000 stocks listed on the NSE. But not all of them trade regularly. The number of securities actually traded on the NSE was more-or-less flat between 2012 to 2020. But then, it spiked — from ~2400 to ~3800!

That could mean more stocks have liquidity now. Or, more likely, it could mean that all sorts of small and micro scammy stocks suddenly started seeing activity after 2020.

In essence, our markets are filled with speculative mania.

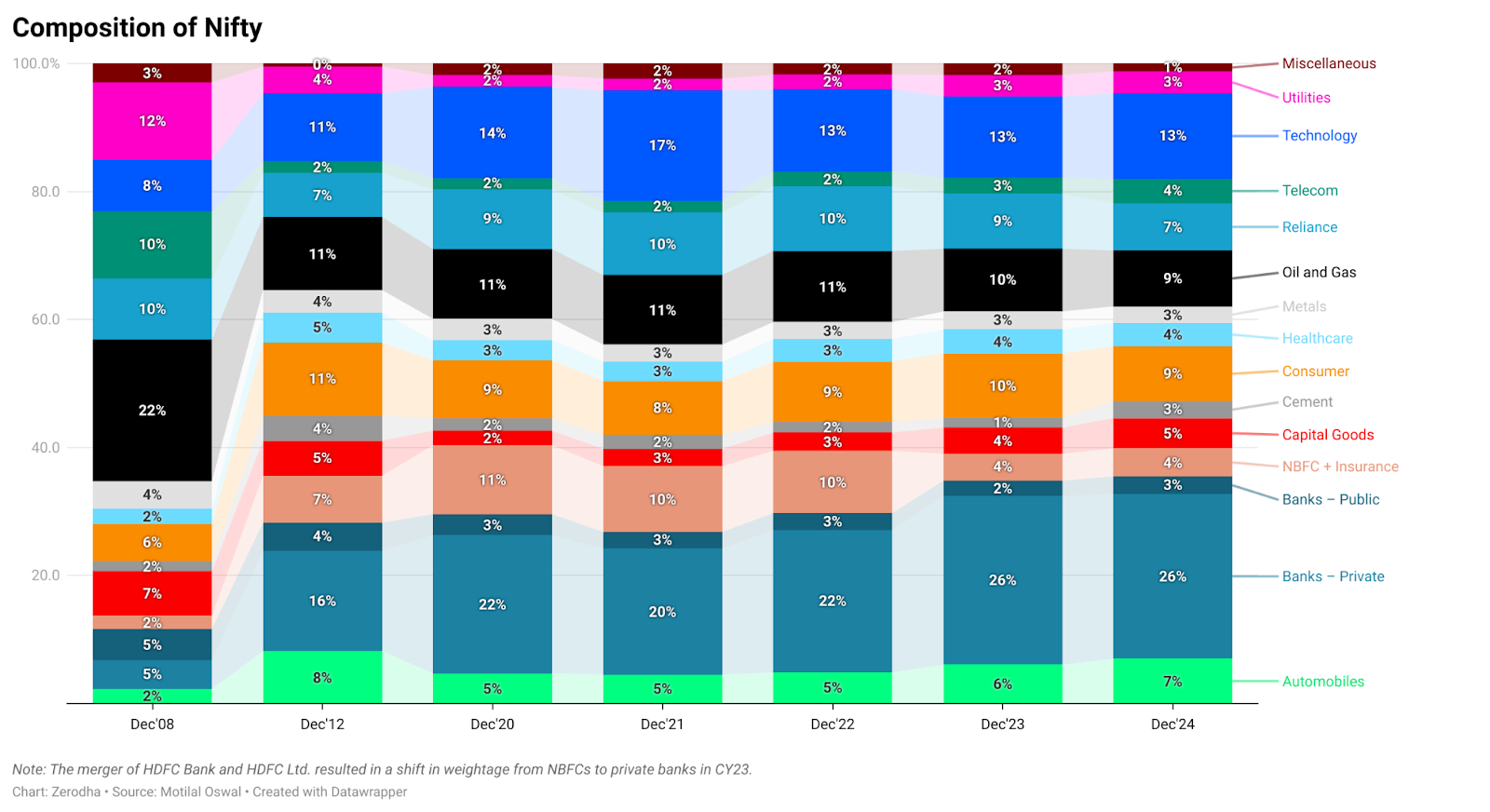

That said, here are a couple of stray charts on how else the markets have changed. One, here’s how the market cap of different sectors in Nifty has changed since COVID-19. The biggest changes in the index weights have been the increase in banks and the reduction in NBFCs, this is due to the HDFC merger. The weightage of IT had reduced and this was offset by an increase in the weight of telecom, auto, and capital goods.

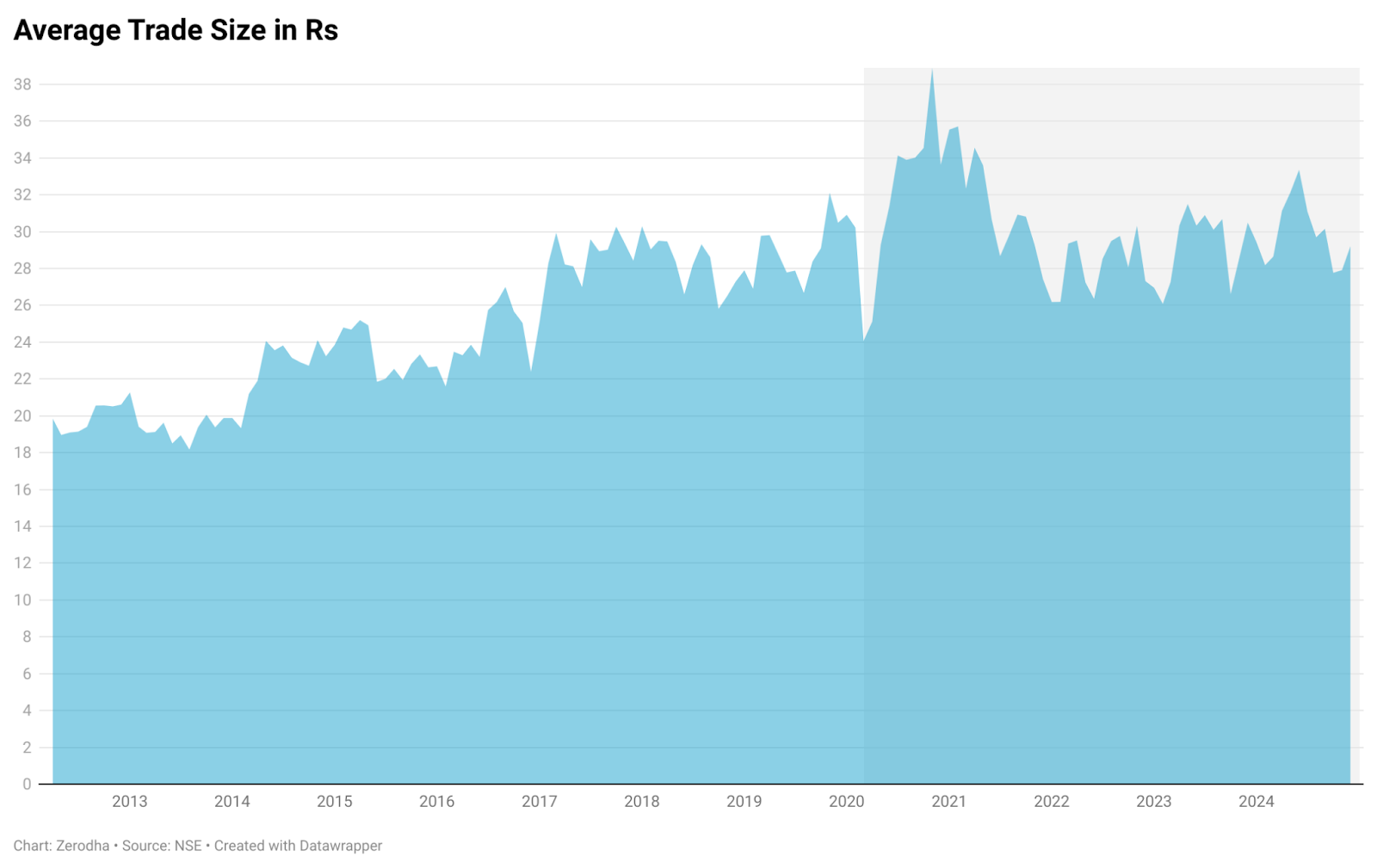

Two, all this while, even as the markets have exploded with activity, the average trade size in the cash market segment has broadly stayed in the range:

The retail revolution

Perhaps the most stunning development of the post-COVID period is the dramatic increase in participation of retail investors.

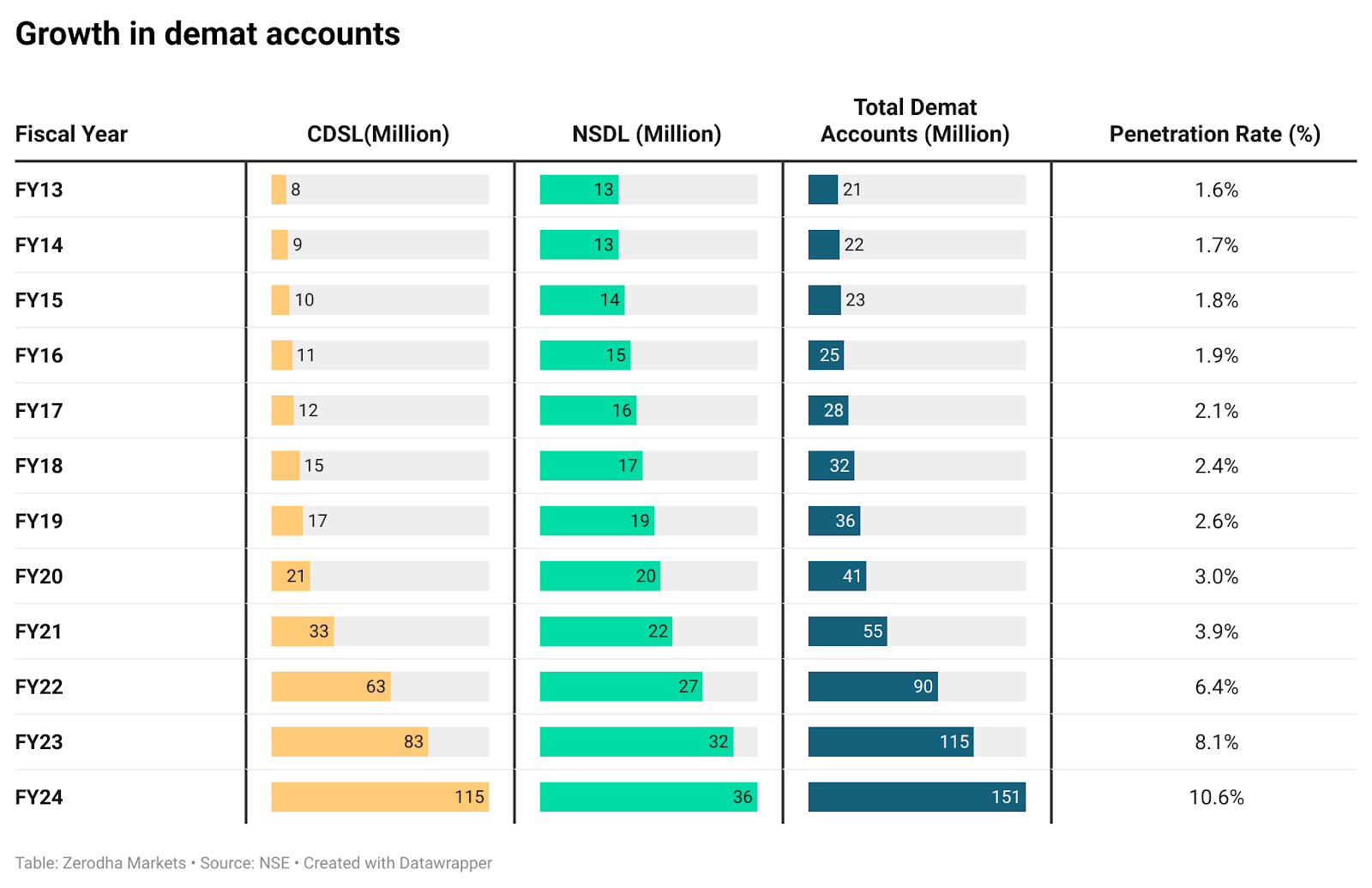

This had long been a headache for the Indian markets: retail participation in the markets had been rising excruciatingly slowly in the decade before COVID-19. Because of this shallow participation, liquidity remained thin, and companies had to think twice before IPO-ing.

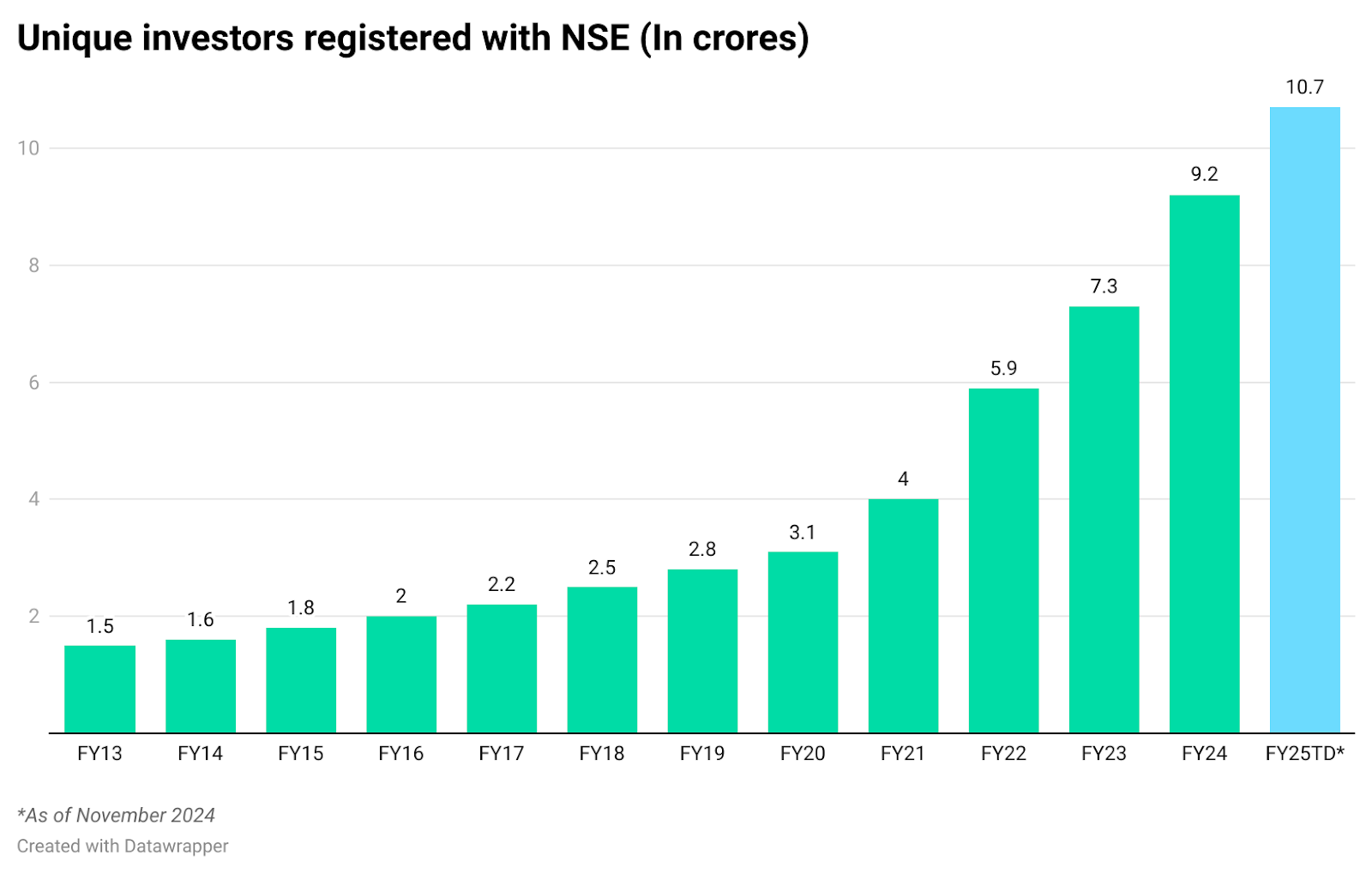

Before COVID, it took 8 years for the number of unique investors in our markets to double. There were 1.5 crore unique investors in the Indian stock market in 2013, and that only doubled in 2020.

But the next doubling just took two years. And now, as 2024 has closed, we have almost 11 crore unique investors. The surge is stunning.

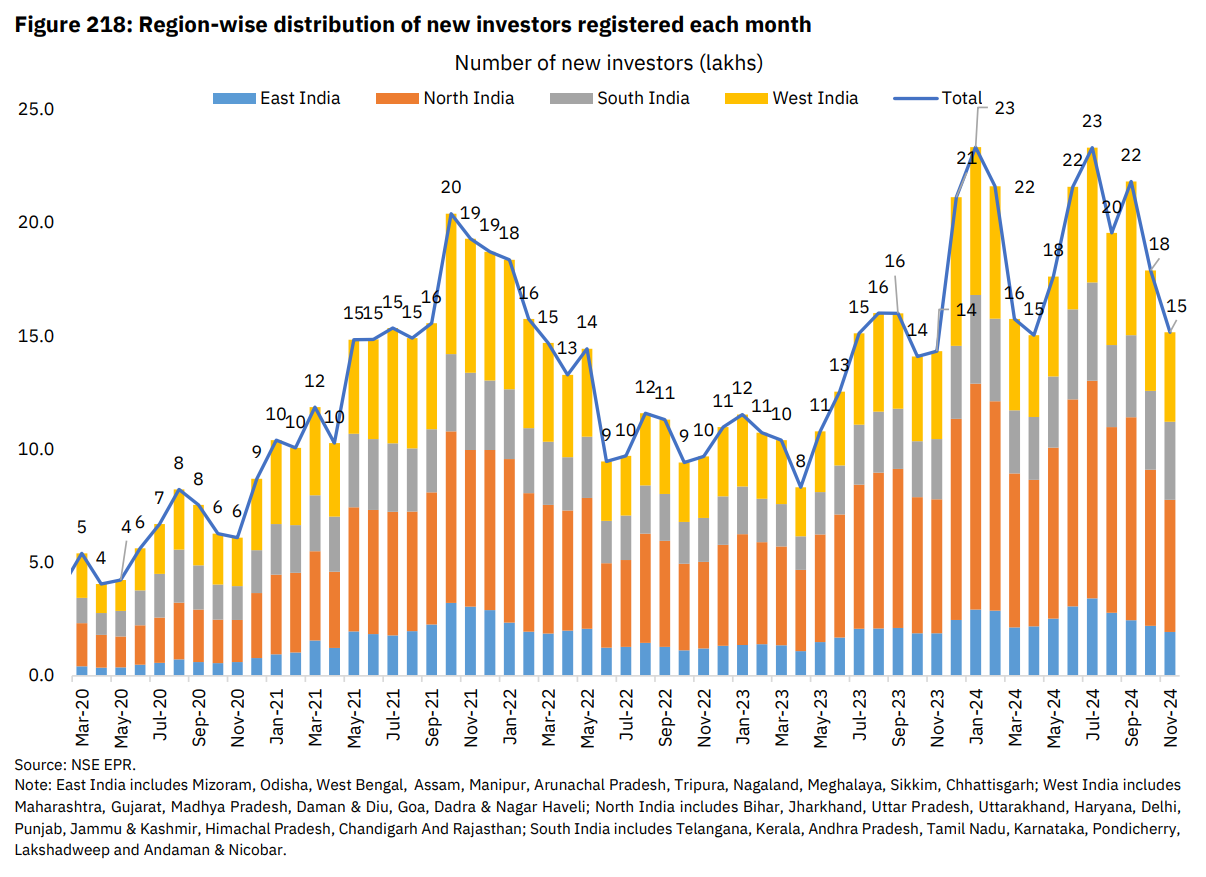

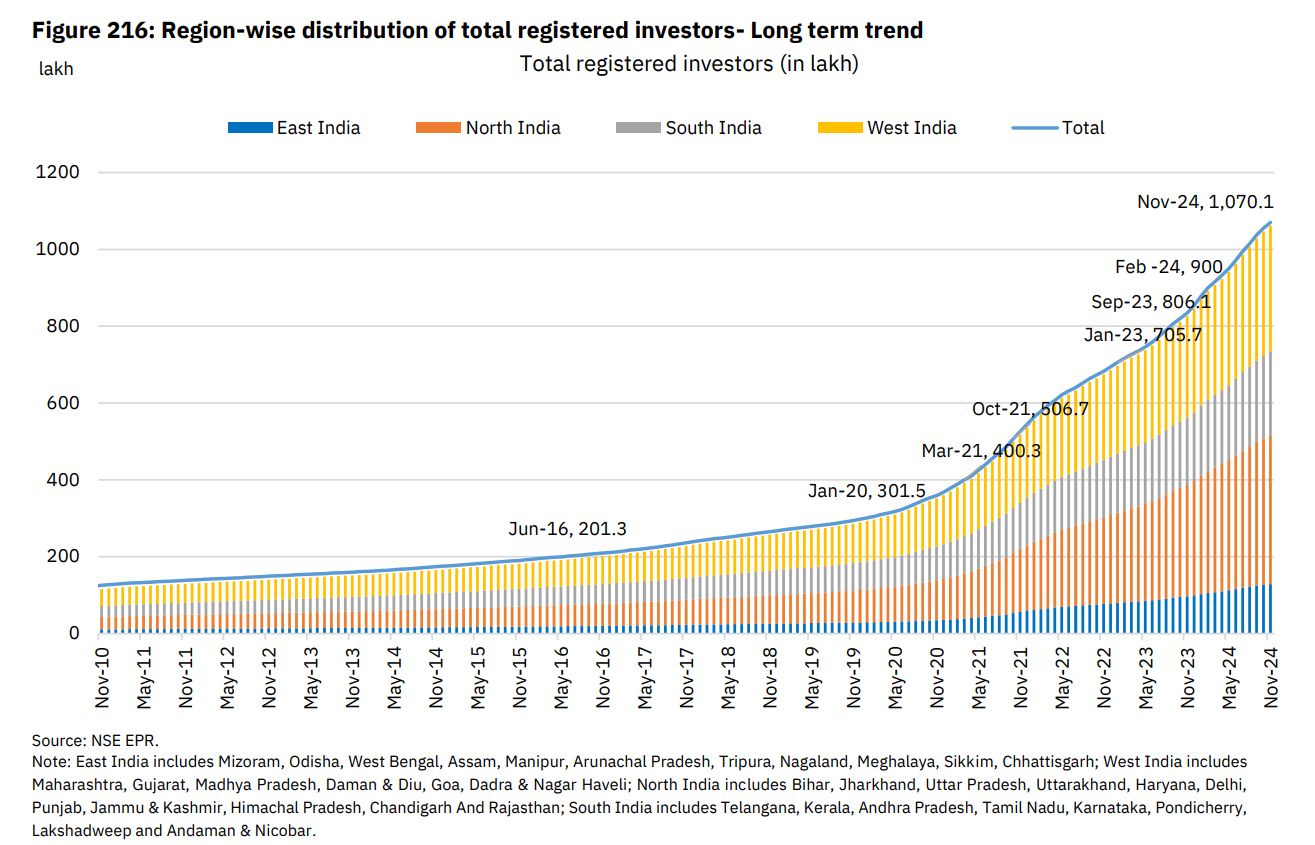

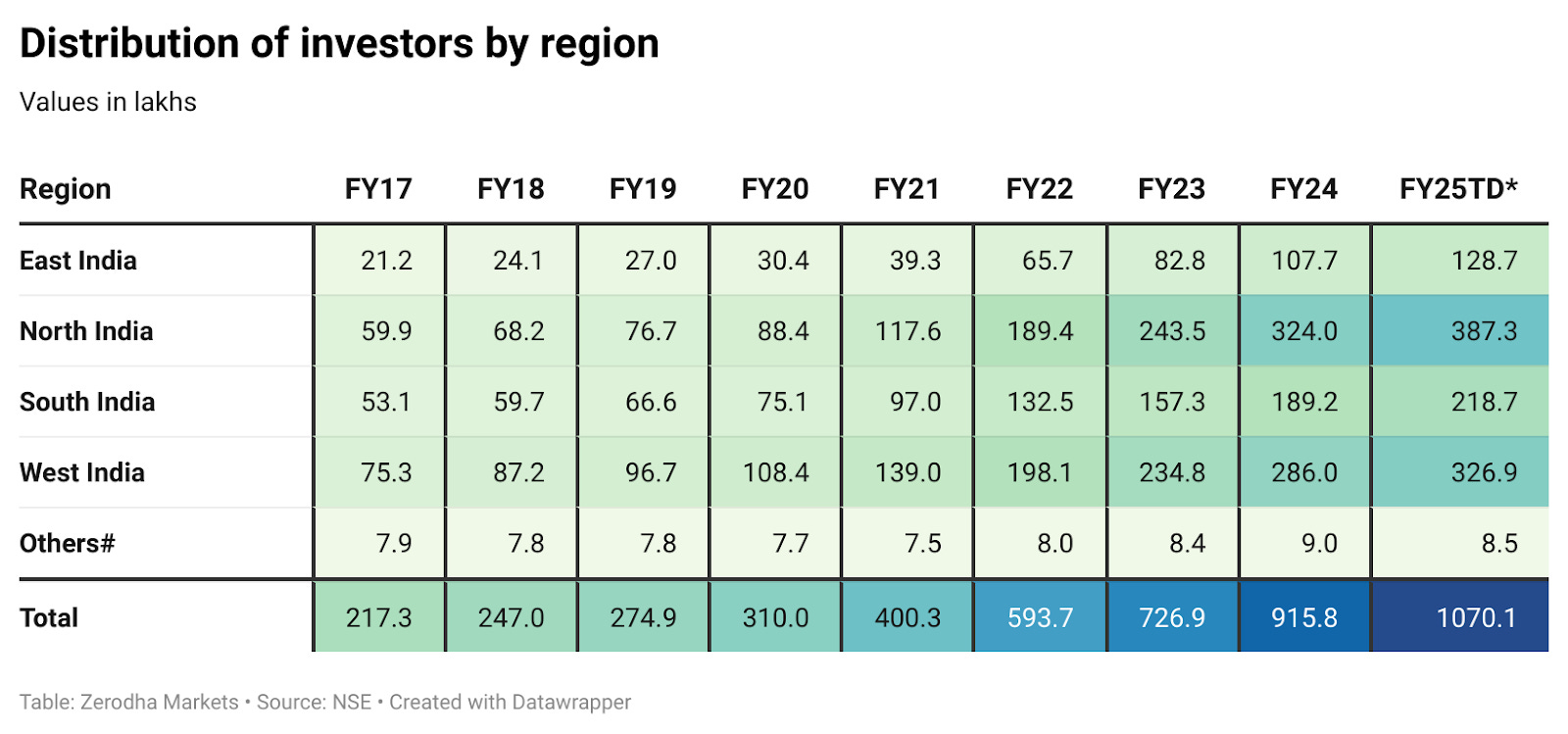

There was a broad-based increase in new investors from all over India, most of this fresh enthusiasm came from North and West India. Here’s how new investors vary across regions:

And here’s a region-wise break-up of total investors. The contribution of North India to our markets was barely negligible five years ago. Now, it’s almost 30% of our total registered investor base.

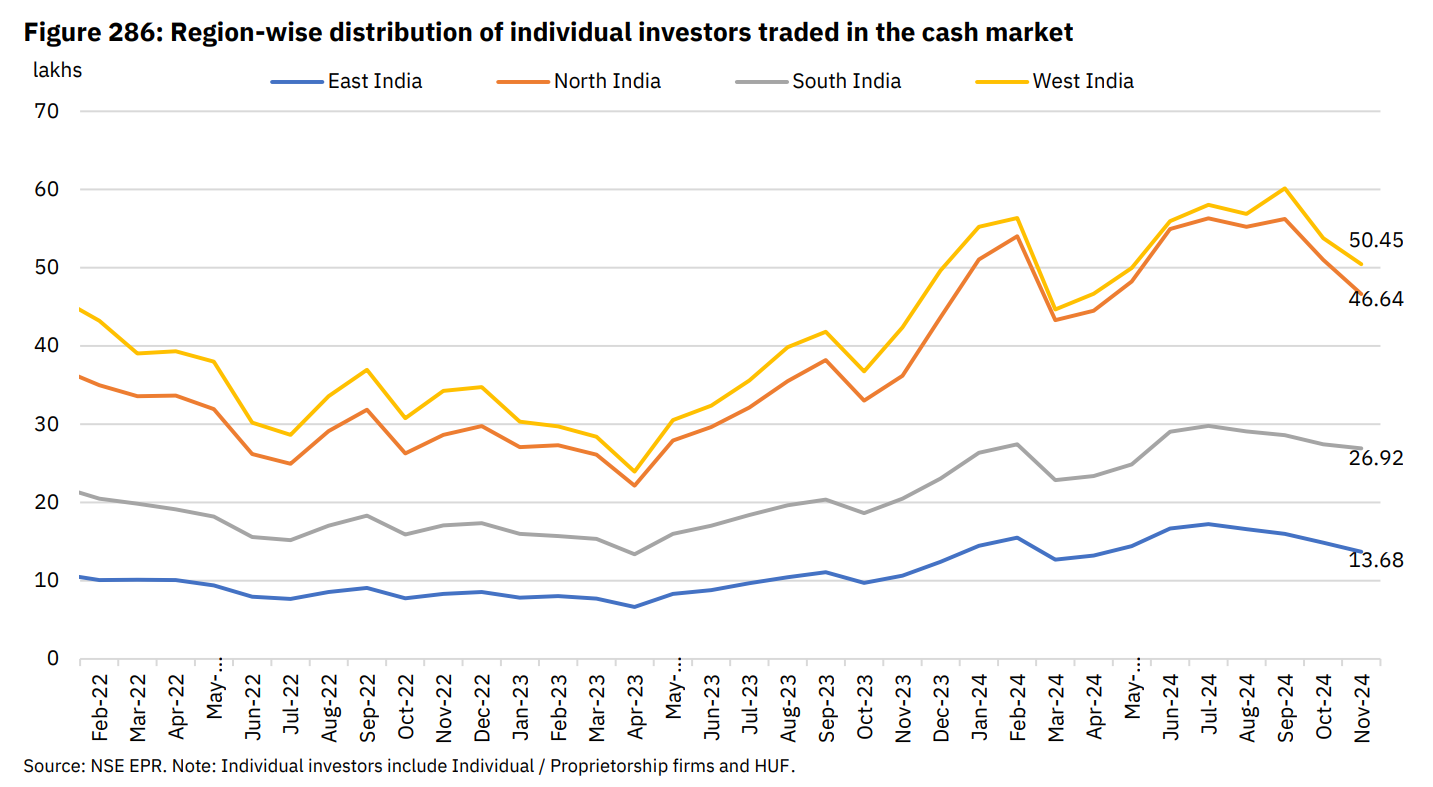

You could also look at the total number of investors who traded in a given month. While trading activity has broadly been stable in South and East India — possibly inching slightly higher — investors elsewhere really took to the markets with gusto.

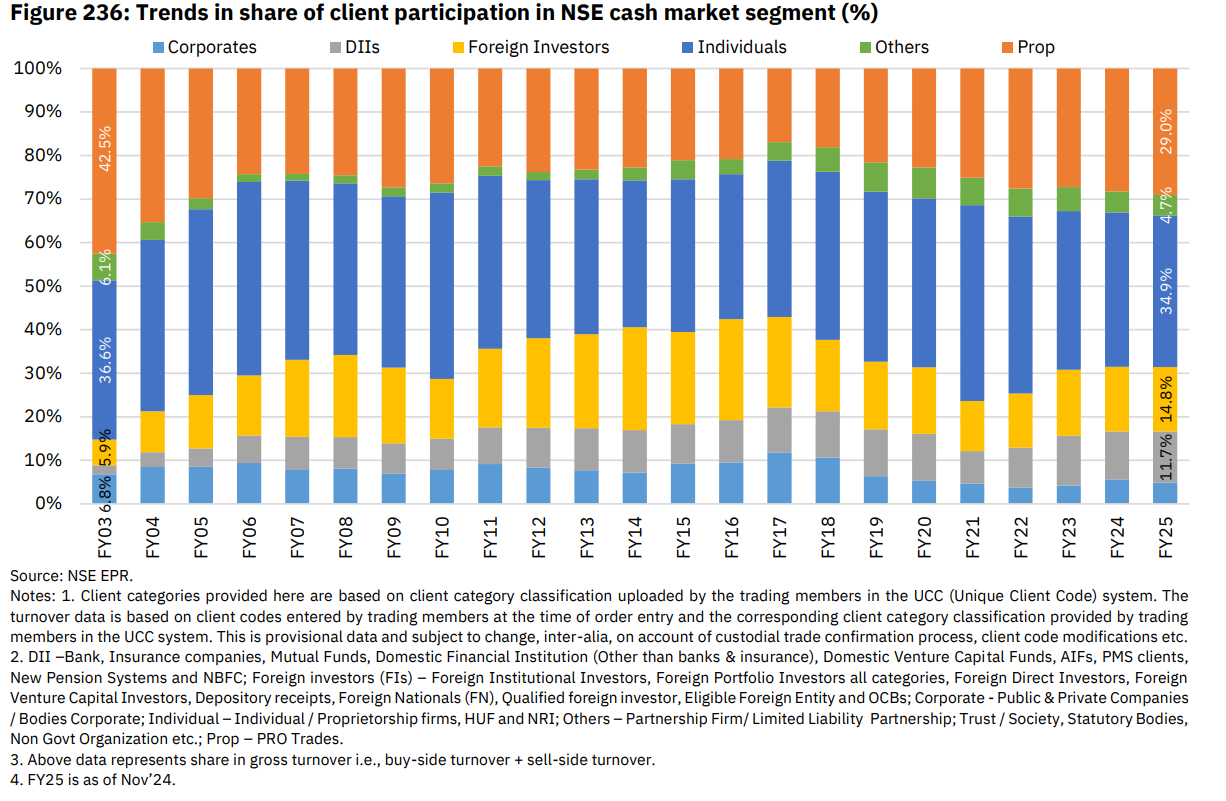

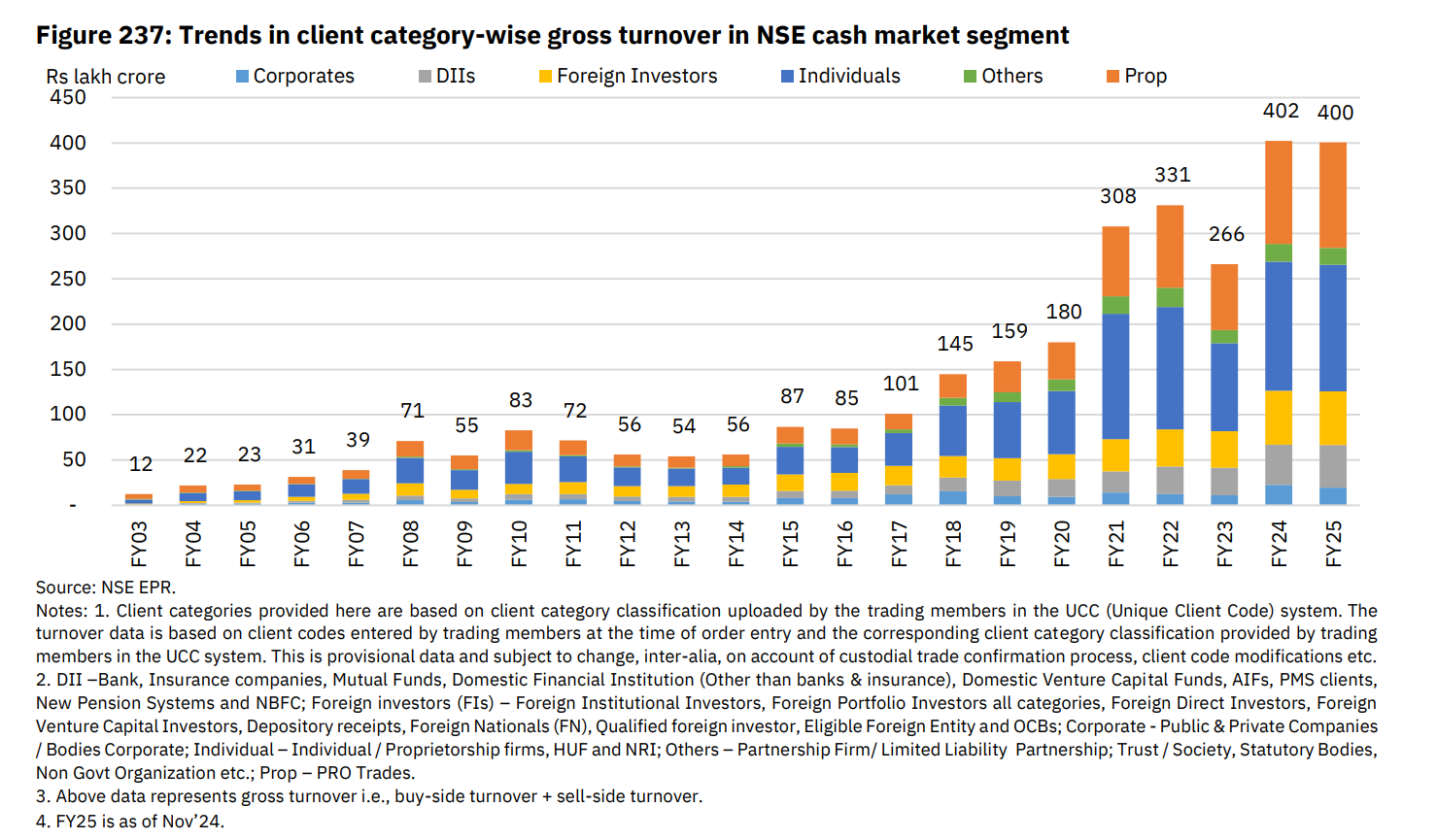

Another way of trying to understand the retail revolution is to see the share and turnover of individual investors compared to other investor segments. Now, individuals have always made for the largest portion of the cash segment, accounting for over 30% of the participation there. During COVID, though, that had briefly jumped to a massive peak of over 45%, before moderating back to 35%.

Source: NSE Pusle

Turnovers tell the same story, but help you picture how much the magnitude of their activity has gone up. Individual investors have remained the largest contributors to the cash segment, followed by proprietary, or “prop” traders.

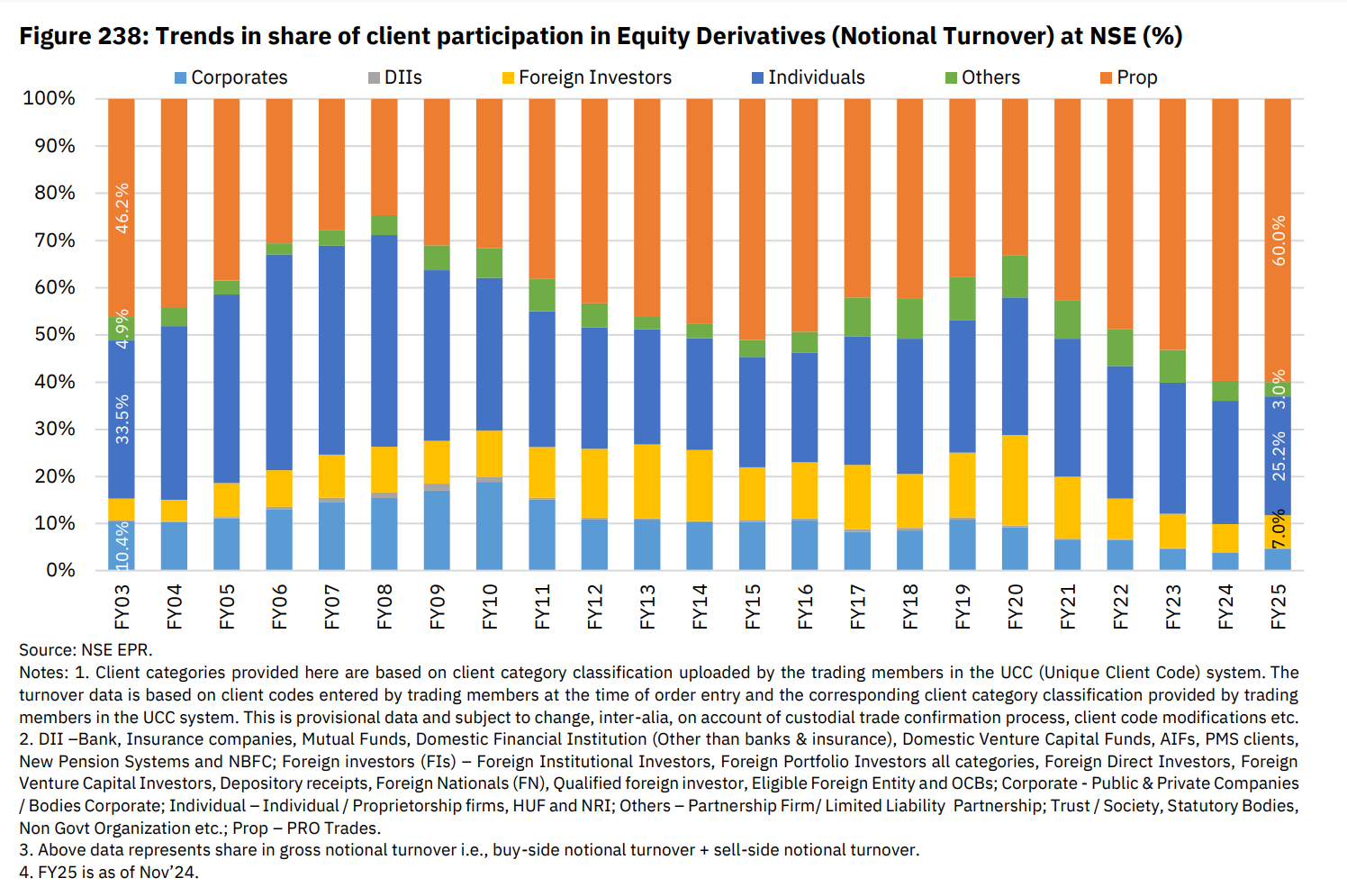

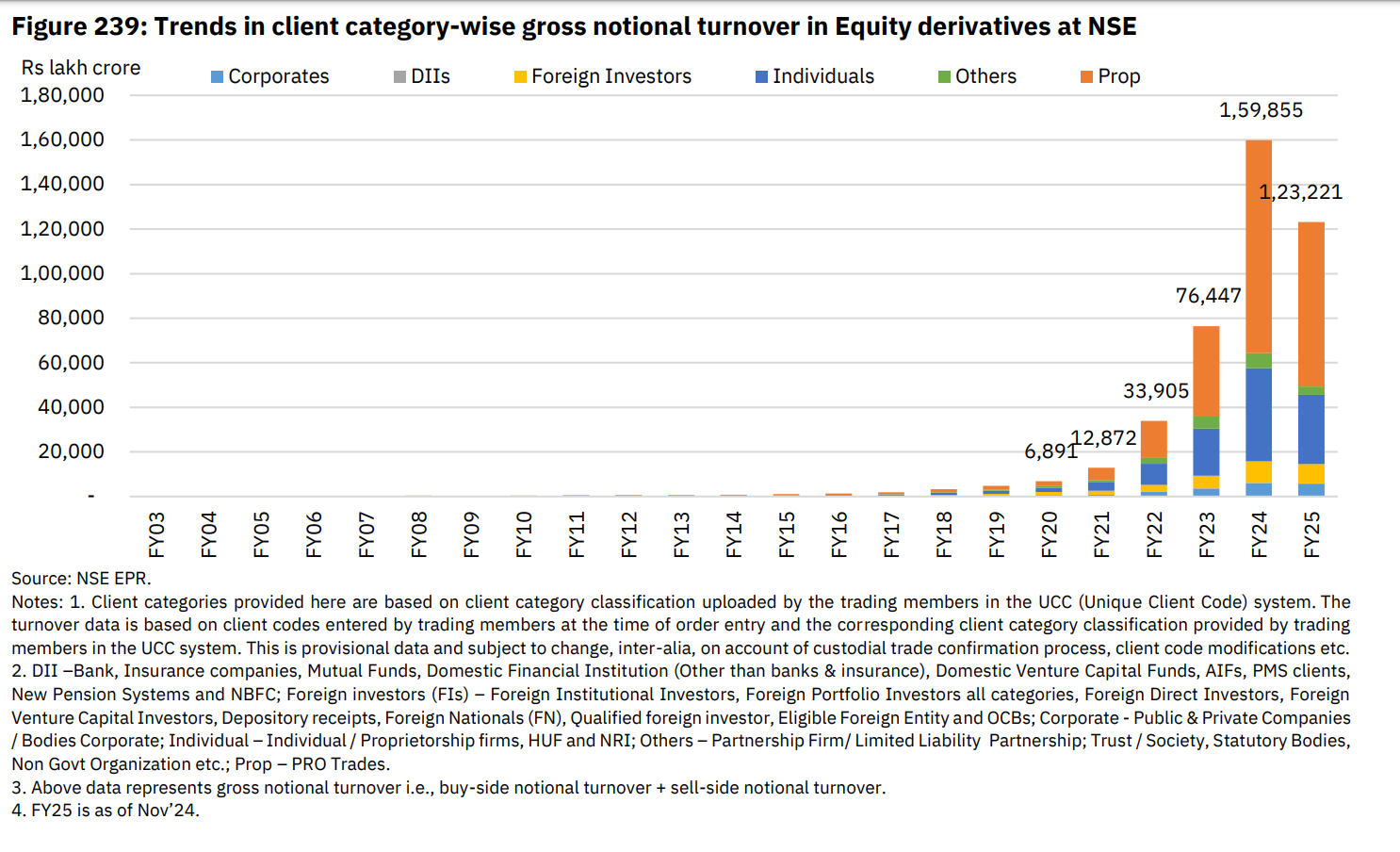

Interestingly, things were a little different in the F&O segment. In absolute terms, retail participation in the segment has increased quite dramatically even there. But they’re dwarfed by prop traders, who’ve taken the market over. These make for more than half the segment — both by participation and turnover.

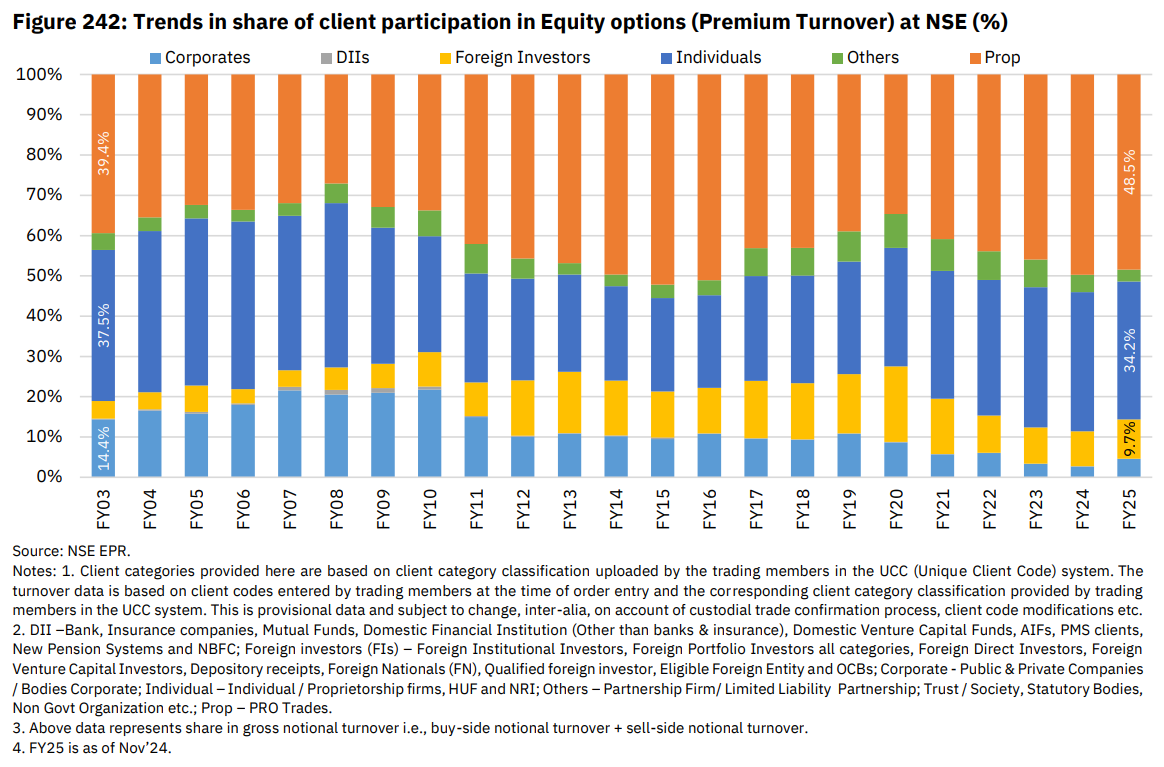

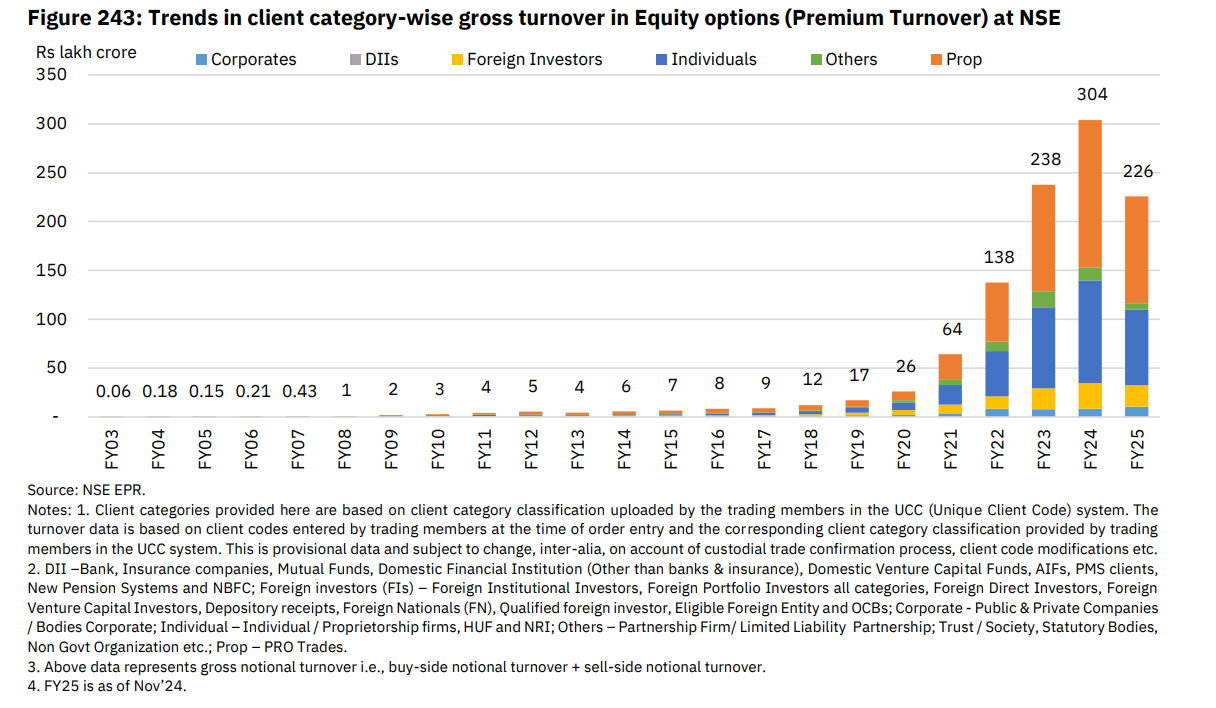

You see something similar with equity options. Retail investors upped their activity by quite a bit, but prop traders blow them out of the water:

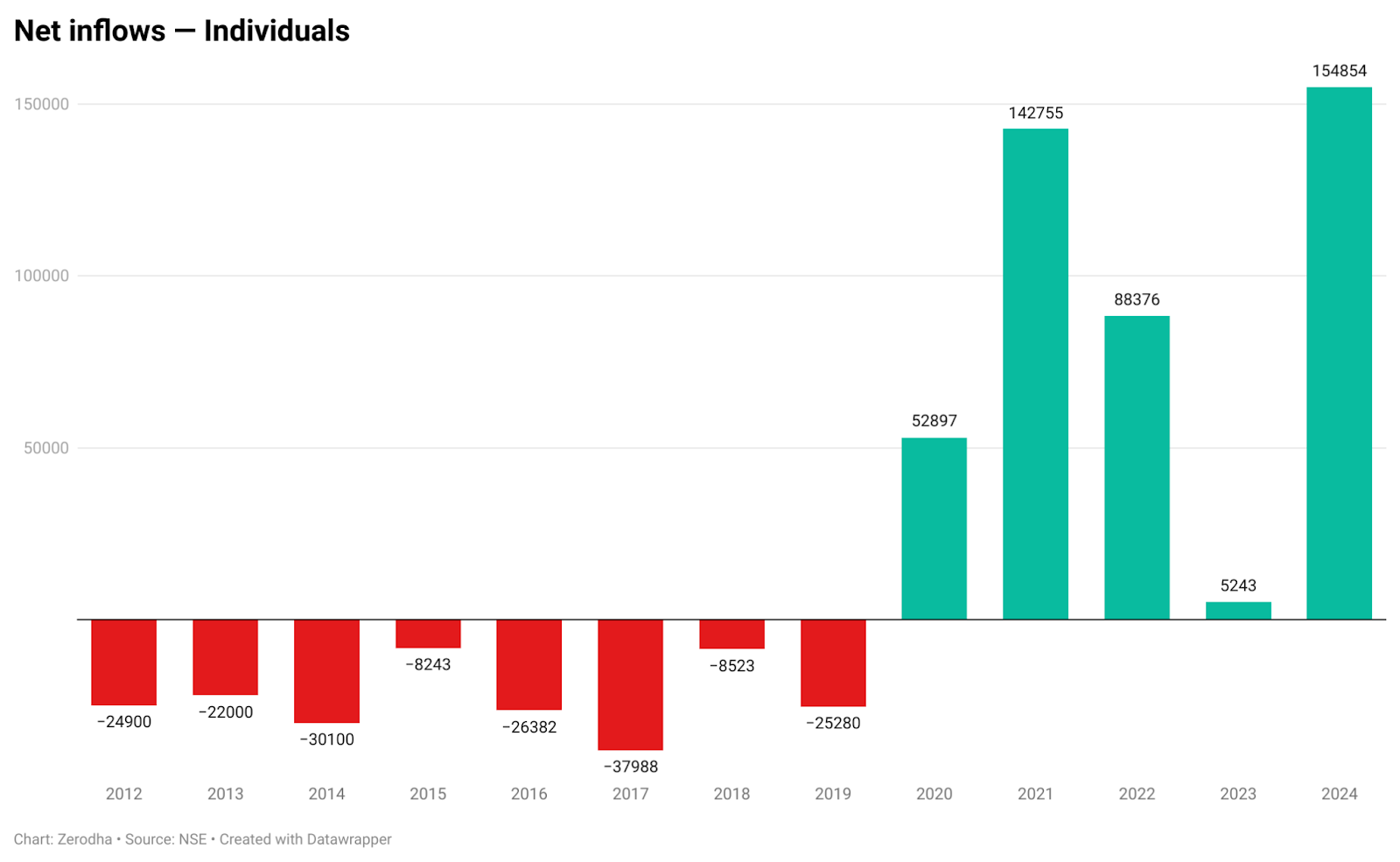

One place the retail revolution really shows up is in the flows. Because here’s the thing: individuals had been cutting down their trading activity before the pandemic hit. Individual flows into direct equities were net negative for eight years.

But post-COVID, things changed. Retail investors have now invested a total of Rs 4.4 lakh crores in the markets. Participating directly. This excludes all the money they put in mutual funds! That’s nuts.

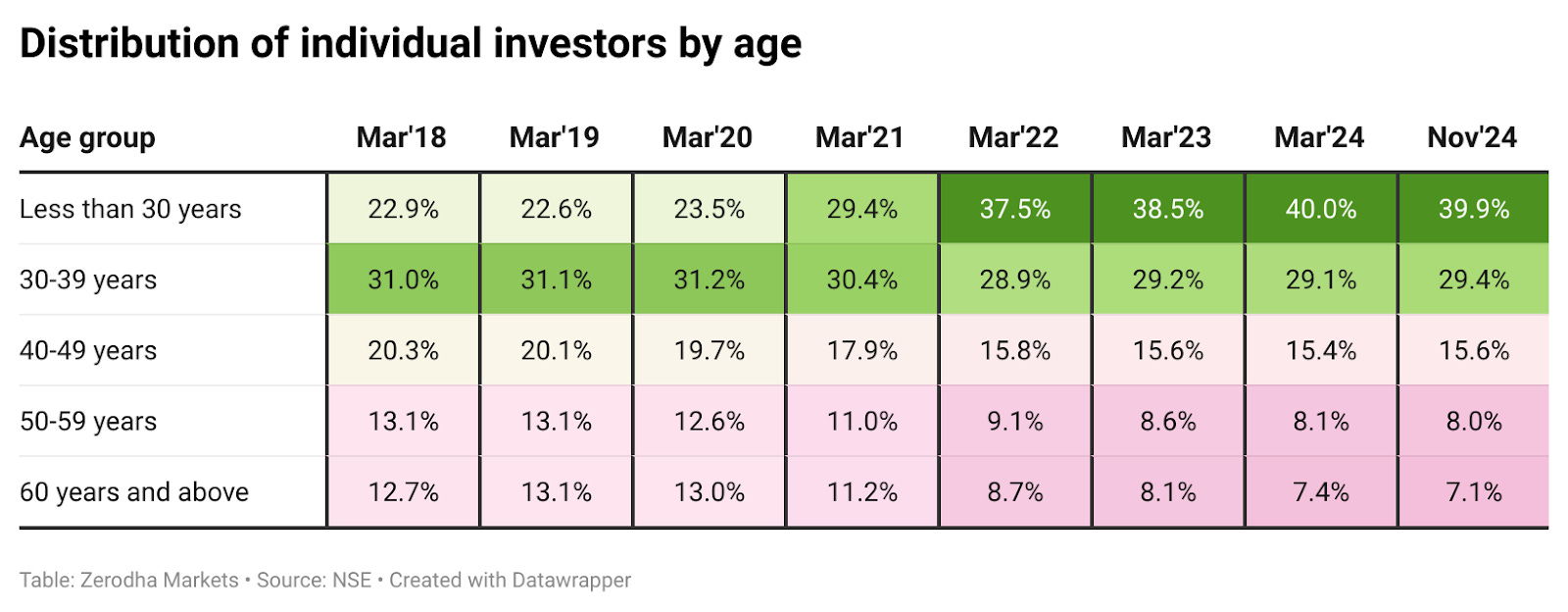

We’re getting younger

An interesting and, in my view, positive development over the last five years was that the Indian stock markets have become younger as a whole. When COVID was breaking out, only 23% of Indian investors were younger than 30. The share of under-30 investors has almost doubled since — to 40%. This is a massive long-term plus, in my view. I wrote about this recently.

The growth of mutual funds

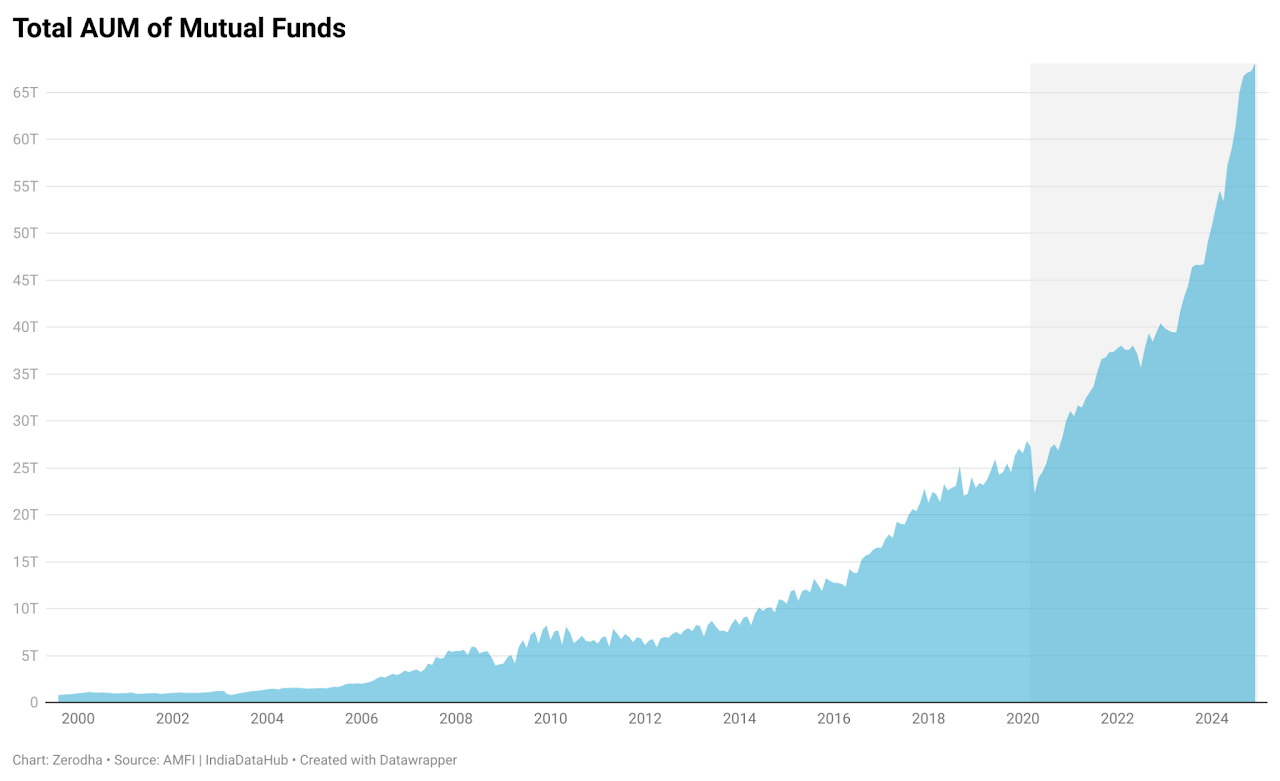

The Indian mutual fund industry has grown spectacularly in the last five years.

In March 2020, the combined AUM of the industry was Rs. 22 lakh crores. By November 2024, it was almost thrice that high — standing at Rs. 68 lakh crores.

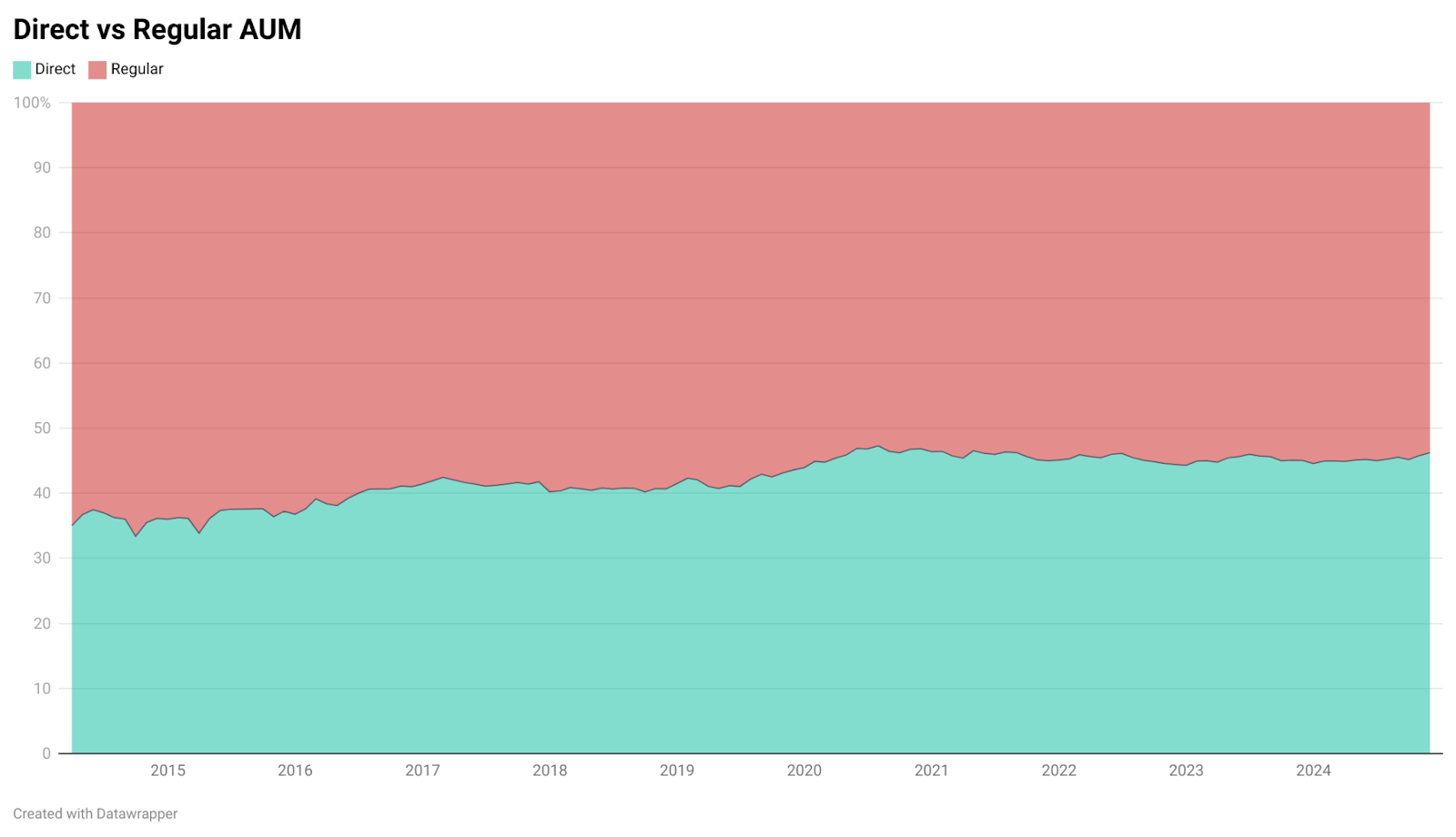

Almost half the industry’s AUM is now in direct plans.

(One thing to keep in mind, though, is that institutional investors are big on the direct plans of debt mutual funds. That skews this data a bit.)

Here’s the evolution of direct vs regular mutual funds AUM.

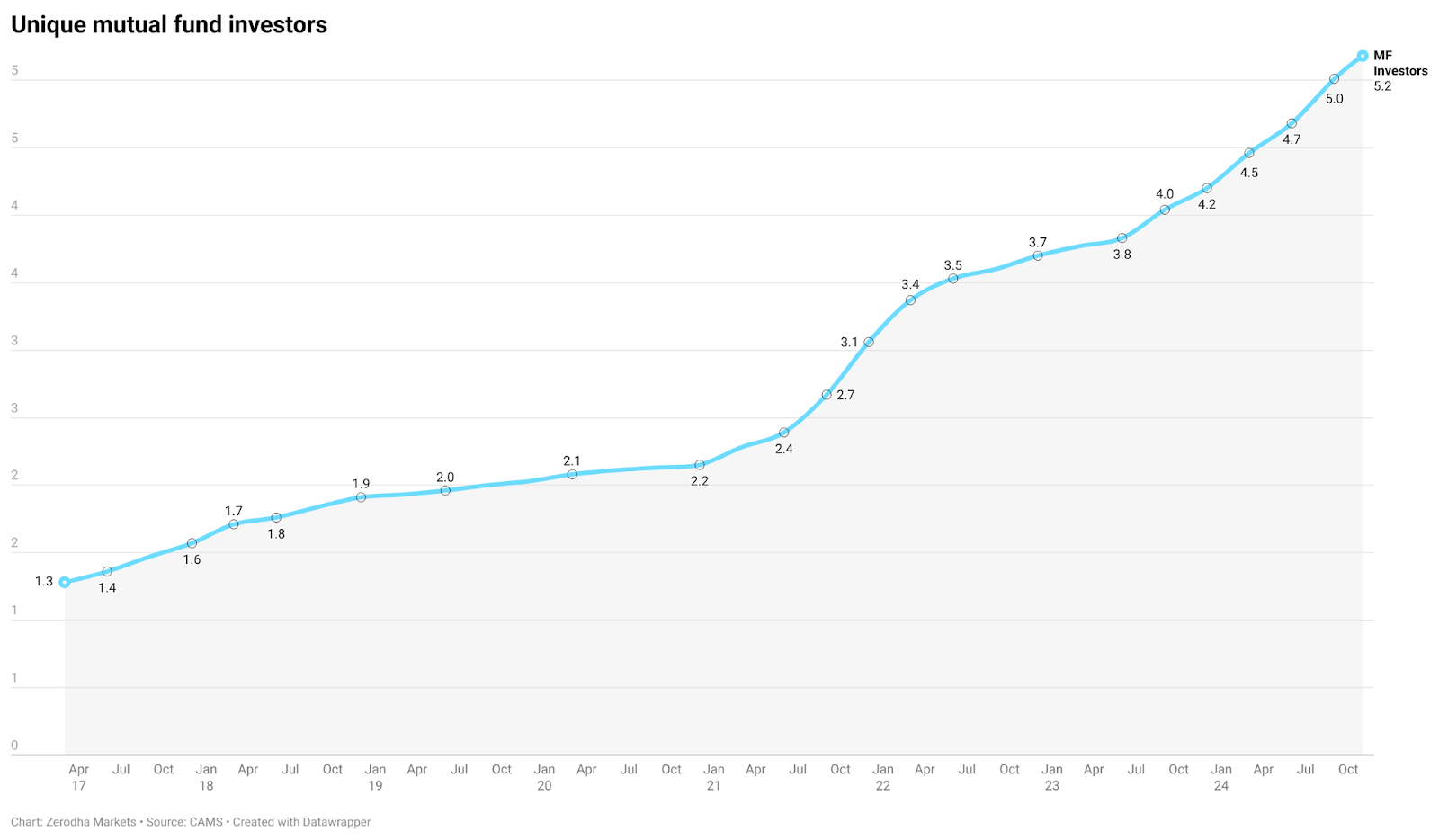

The best data point to measure the growth of the industry’s AUM is to look at the number of unique investors. Circa March 2020, the Indian mutual fund industry had 2 crore unique investors. As of November 2024, this stood at over 5 crores. That’s fairly decent growth. Could’ve been better, perhaps, but it’s a start.

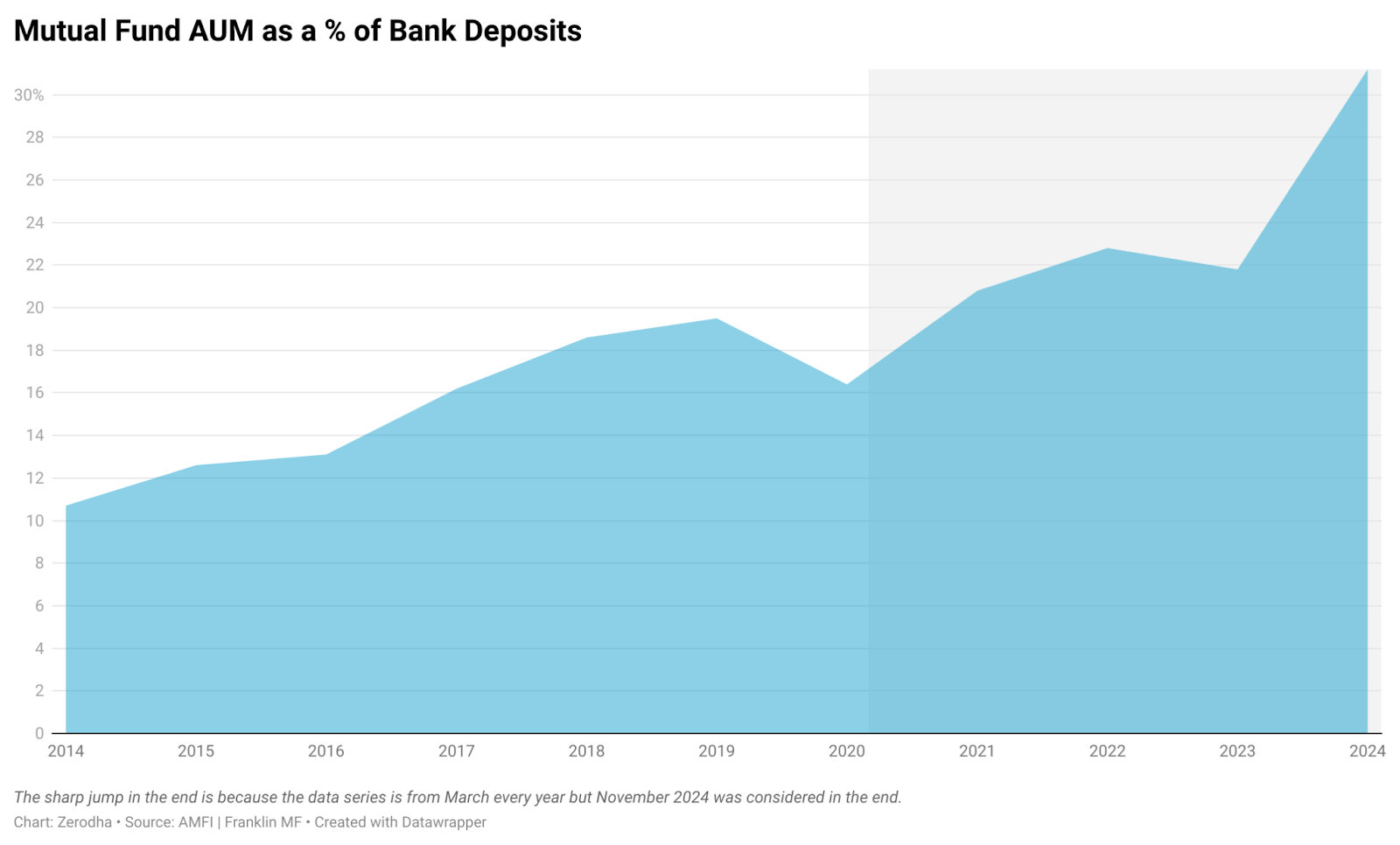

Here’s another way of looking at the industry: back in March 2020, the AUM of mutual funds came up to 16.4% of India’s bank deposits. As of November 2024, it has doubled to 31% of our total bank deposits.

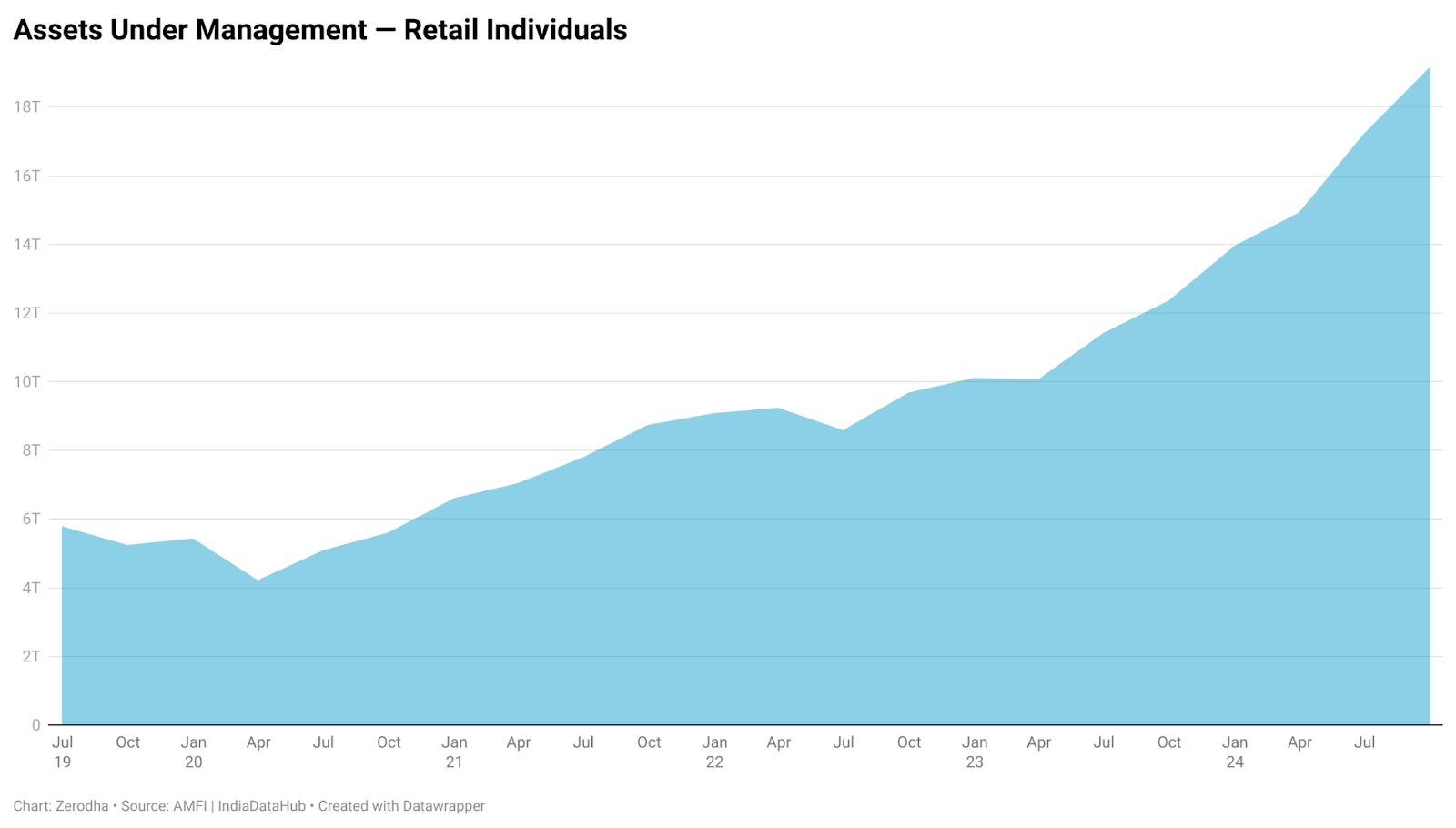

Retail investors hold about 29% of the total AUM of the mutual fund industry. In March 2020, this was at Rs. 4 lakh crores. As of September 2024, this had risen to Rs. 19 lakh crores. This increase includes an uptick in both net inflows and the value of the underlying assets.

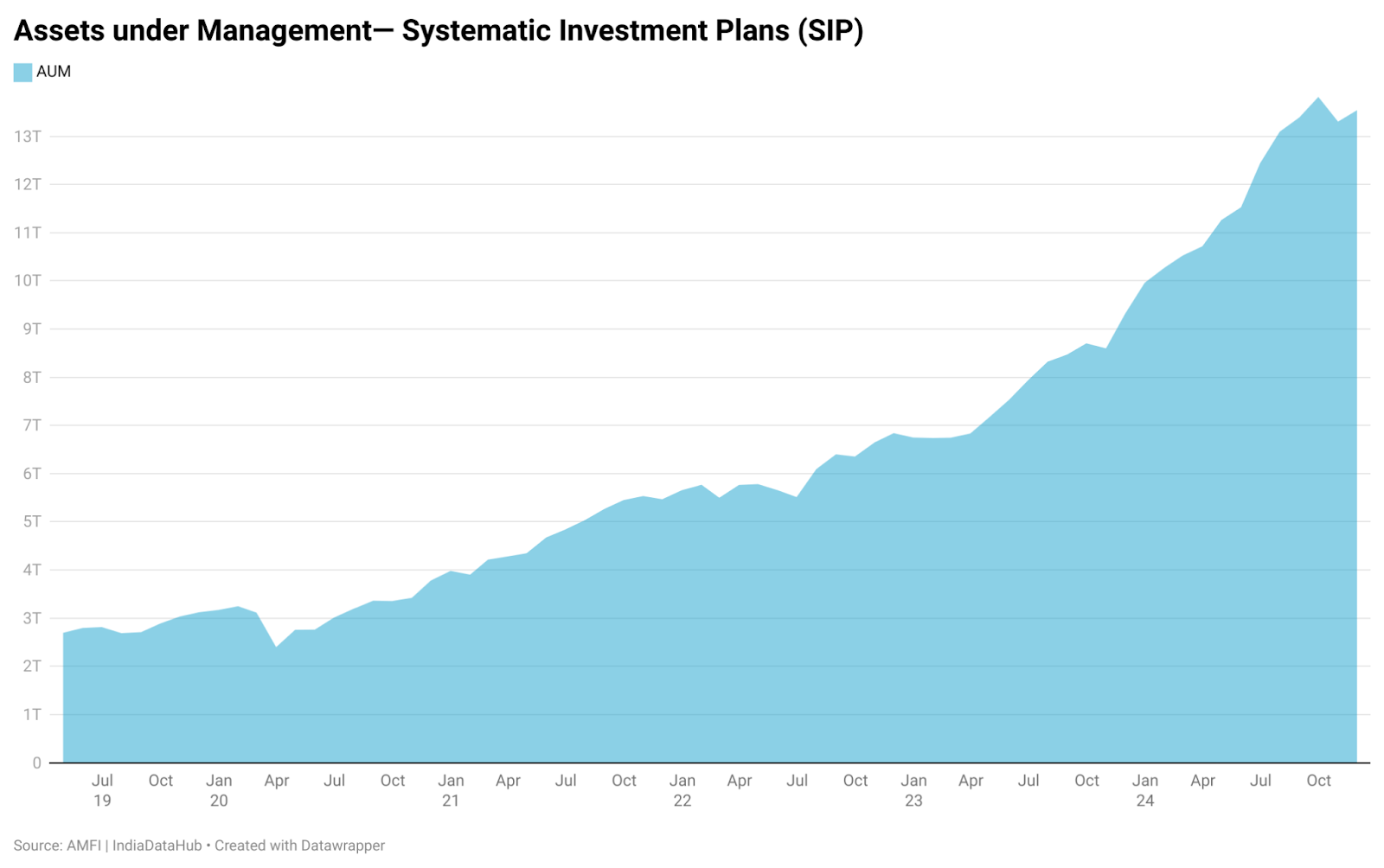

The total of AUM of SIPs, meanwhile, stood at about Rs. 2 lakh crores in March 2020. As of November 2024, it had jumped up all the way to Rs. 13 lakh crores.

In March 2020, the gross monthly inflows into SIPs stood at Rs. 8,500 crores. By November 2024, it was almost three times that — at Rs. 25,300 crores.

Funny, isn’t it? Financial literacy programs have been screaming themselves hoarse pushing equity investments for years. But it was finally a disease, of all things, that actually pushed an equity investment culture in India!

While a lot of people lament about the current speculative frenzy, there’s a good side to this as well. More Indians now invest through mutual funds than ever.

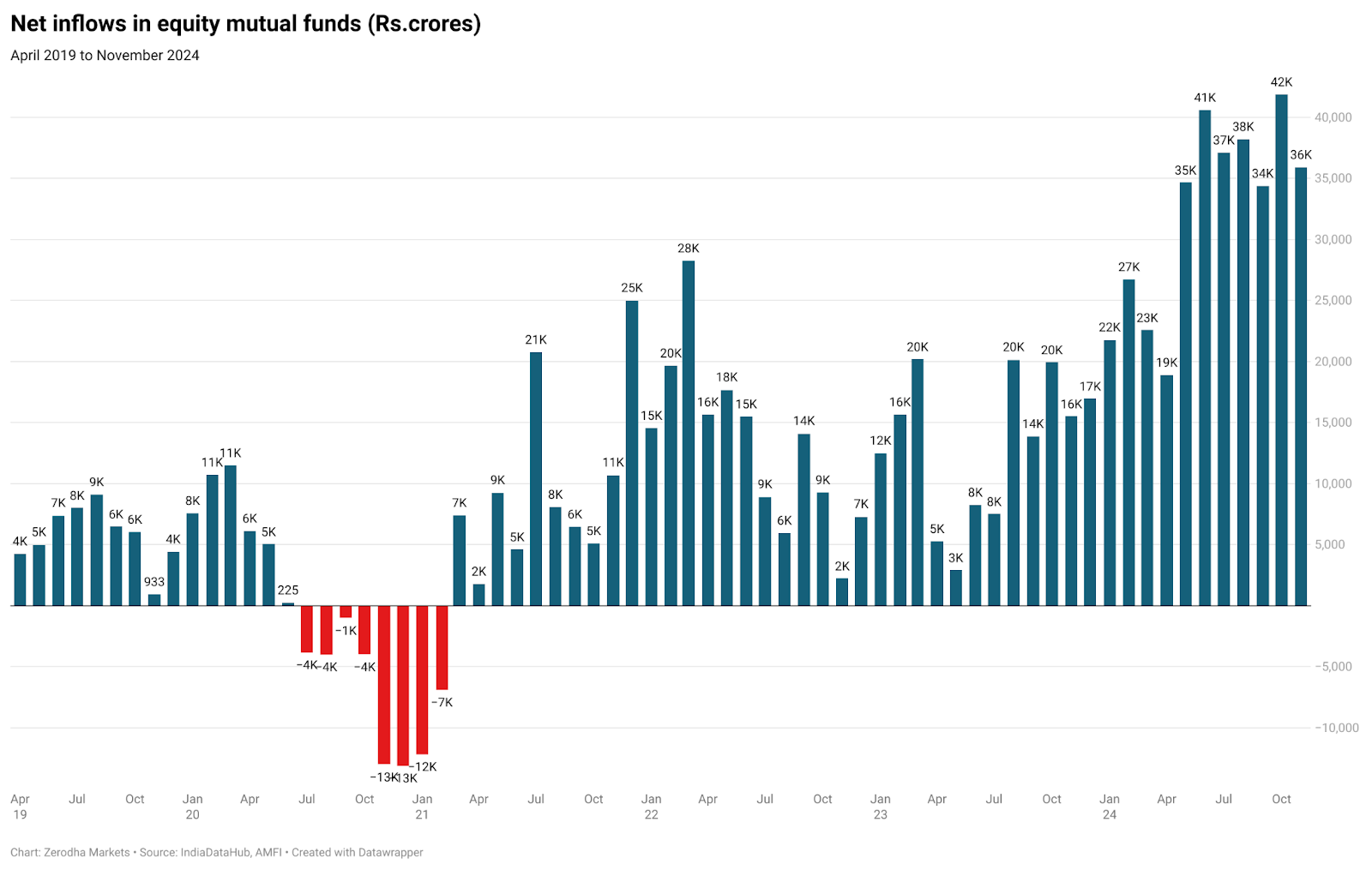

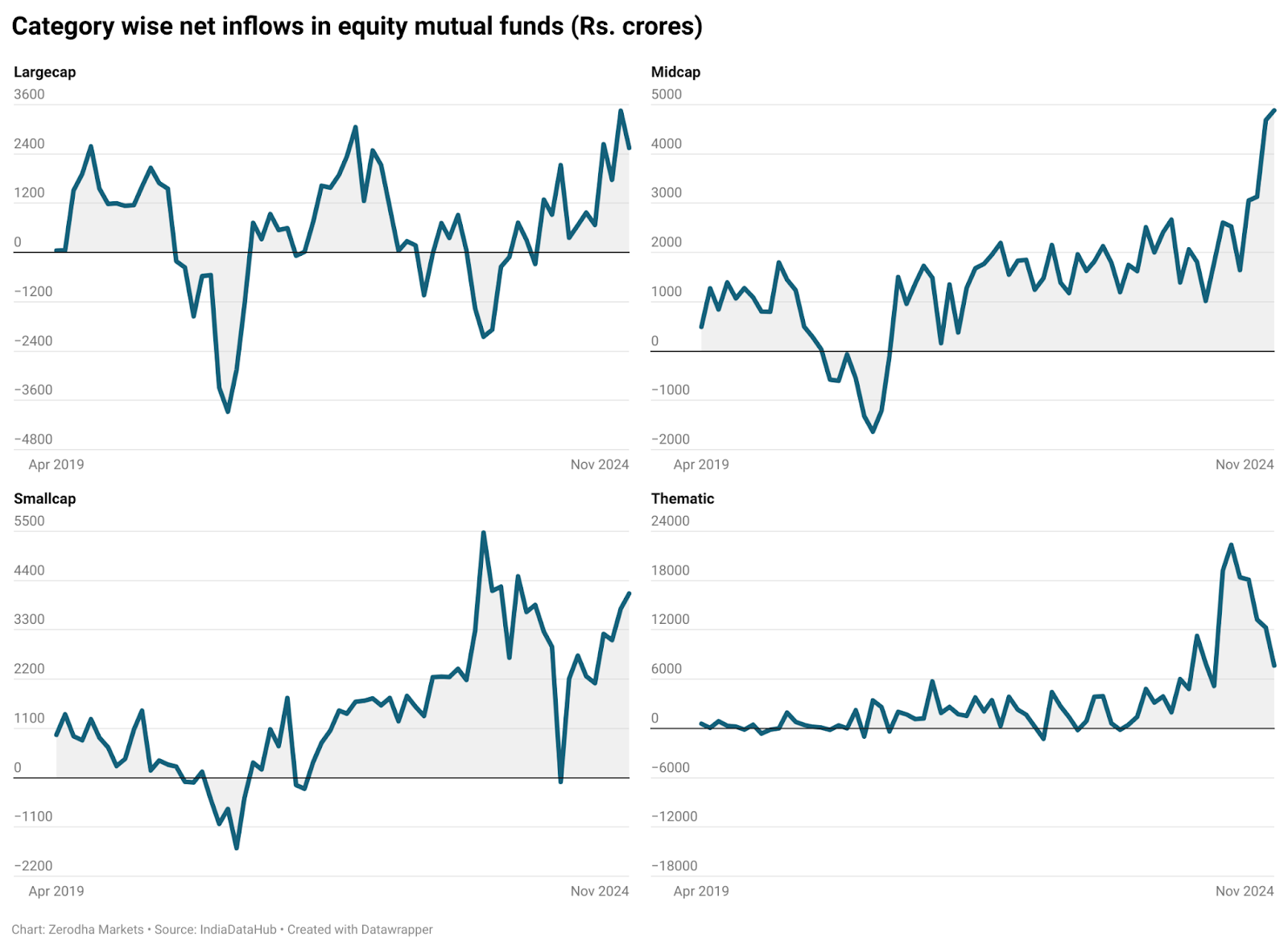

This shows up in both, the flows into mutual funds, as well as the ownership pattern of listed equities.

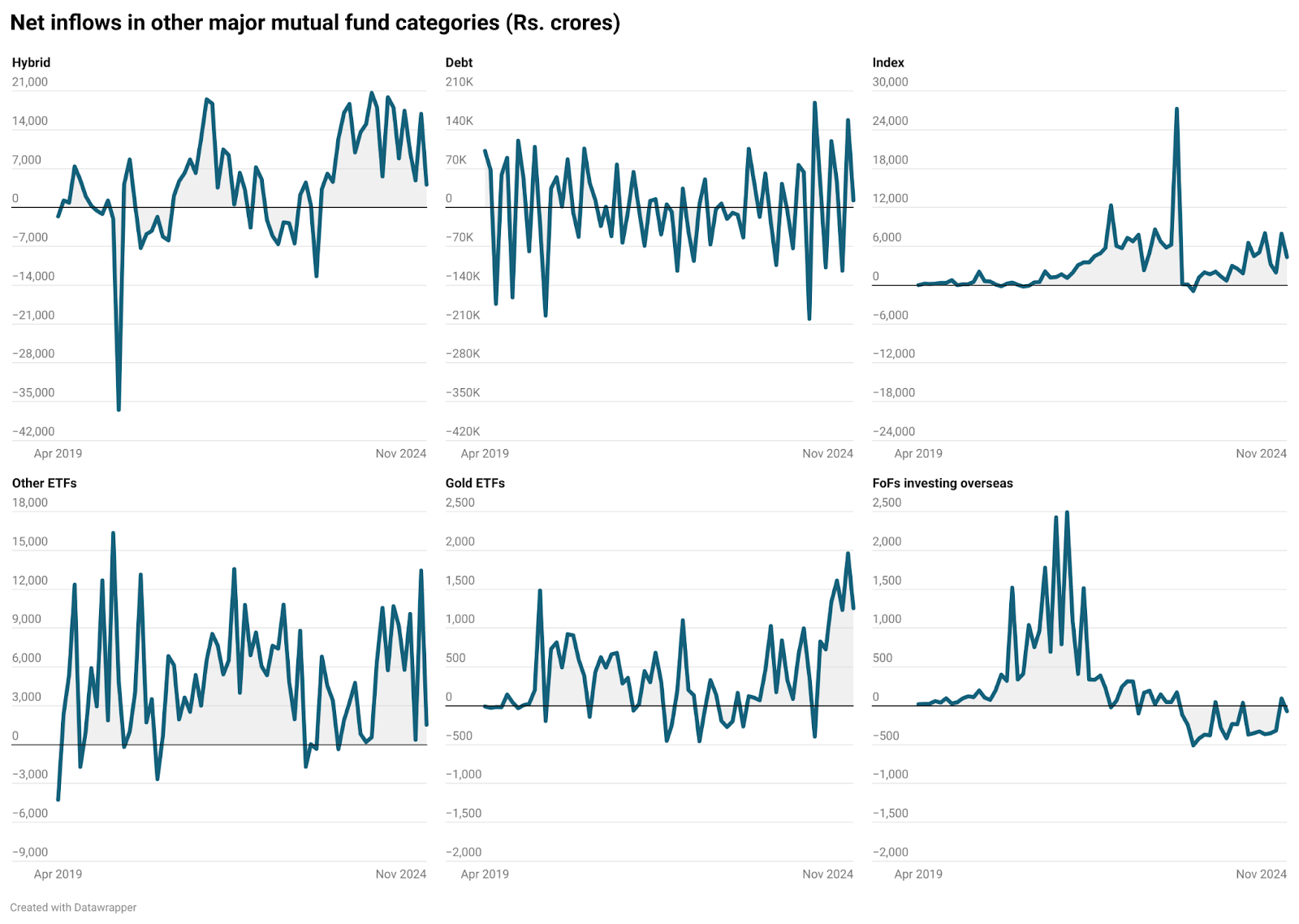

Let me start with flows. Total inflows into mutual funds have more than doubled from the pre-COVID baseline.

Mutual funds tend to be stickier than direct equity flows, which could potentially make this a lasting trend. That’s a really good development for the Indian markets, in the long term. It makes the markets deeper and more resilient.

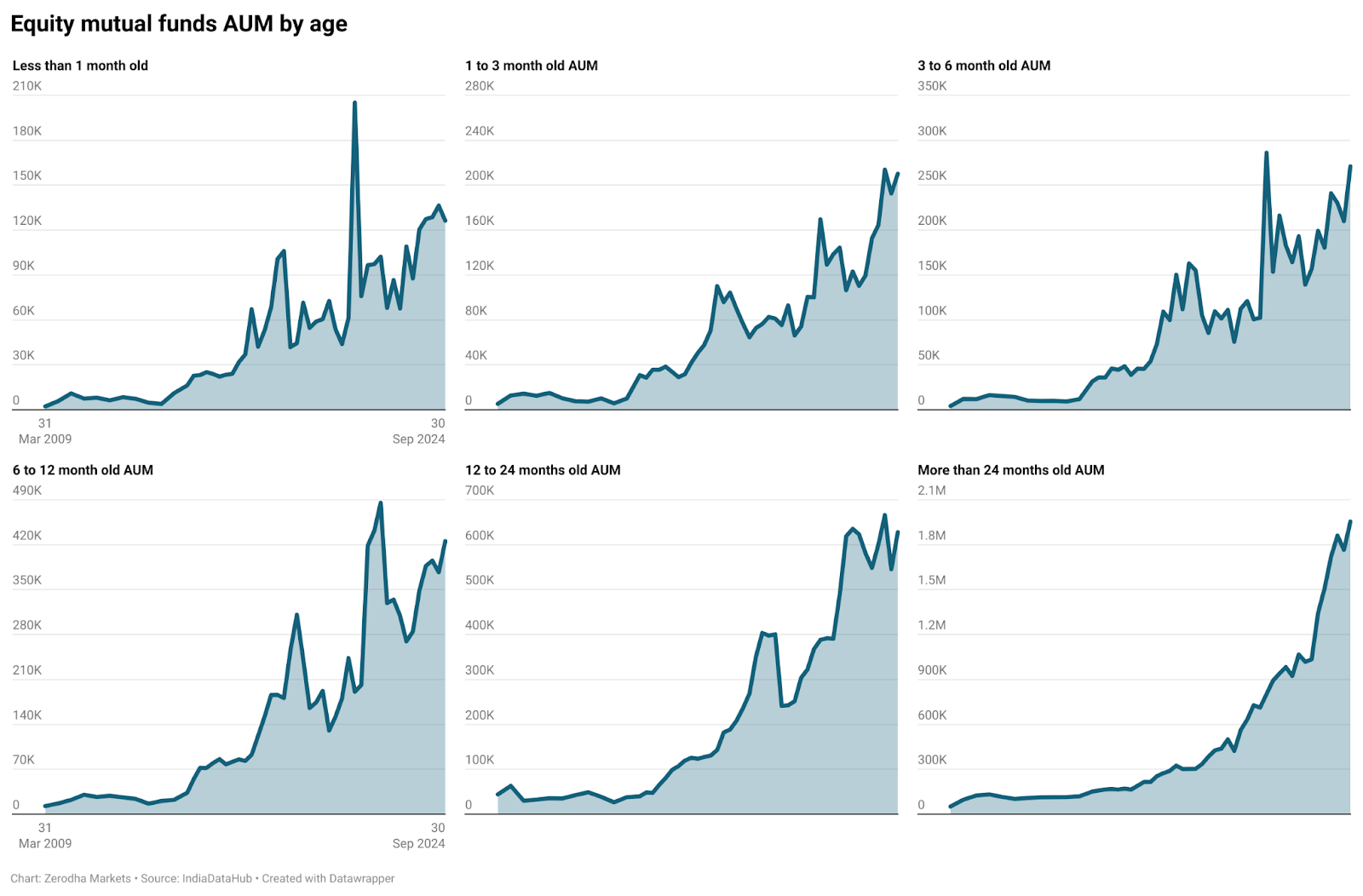

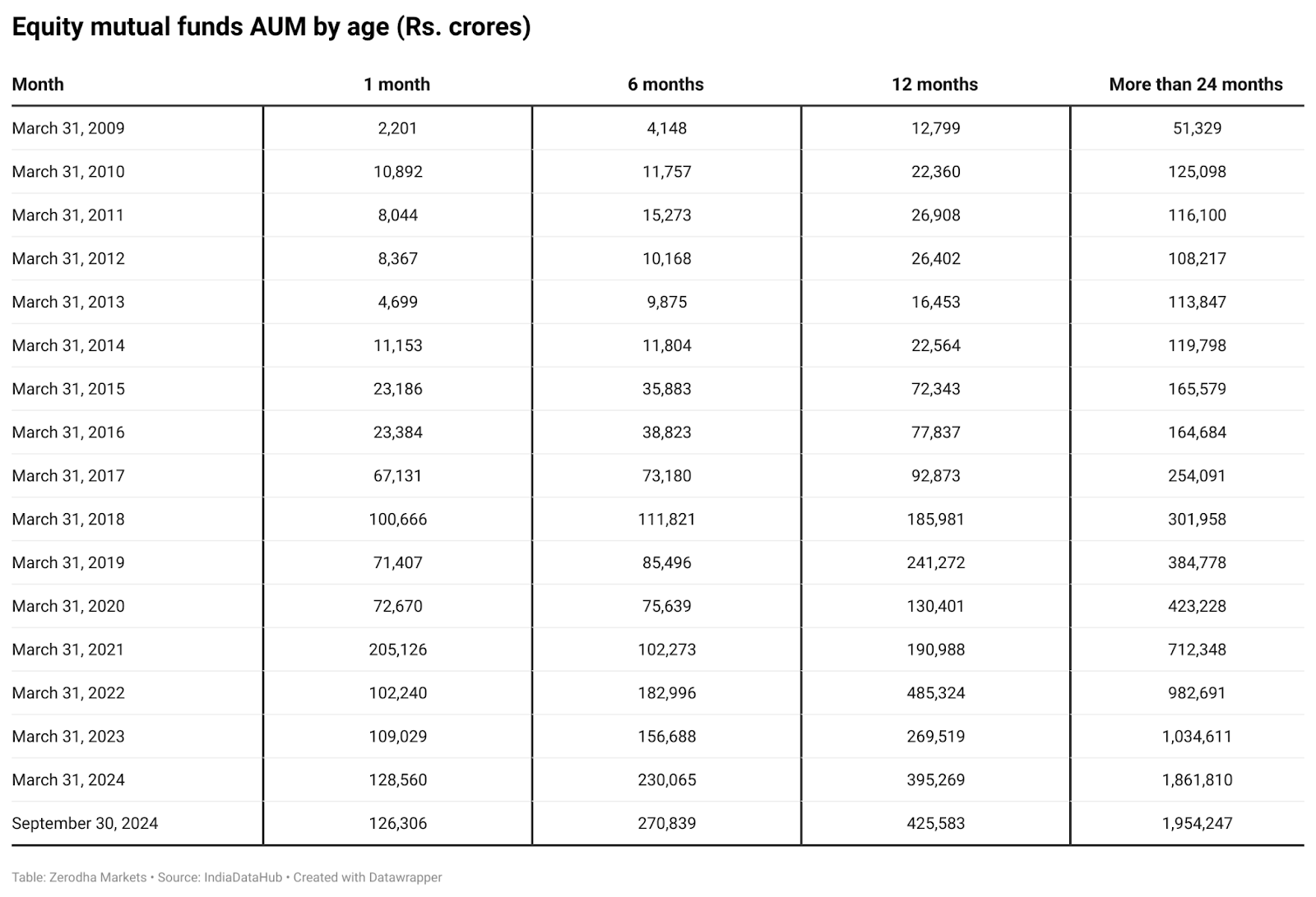

And a lot of this money is sticking around. Here’s an age analysis of mutual fund AUMs:

Thanks to the influx of younger retail investors, there has also been an increase in the equity portion of mutual fund AUMs.

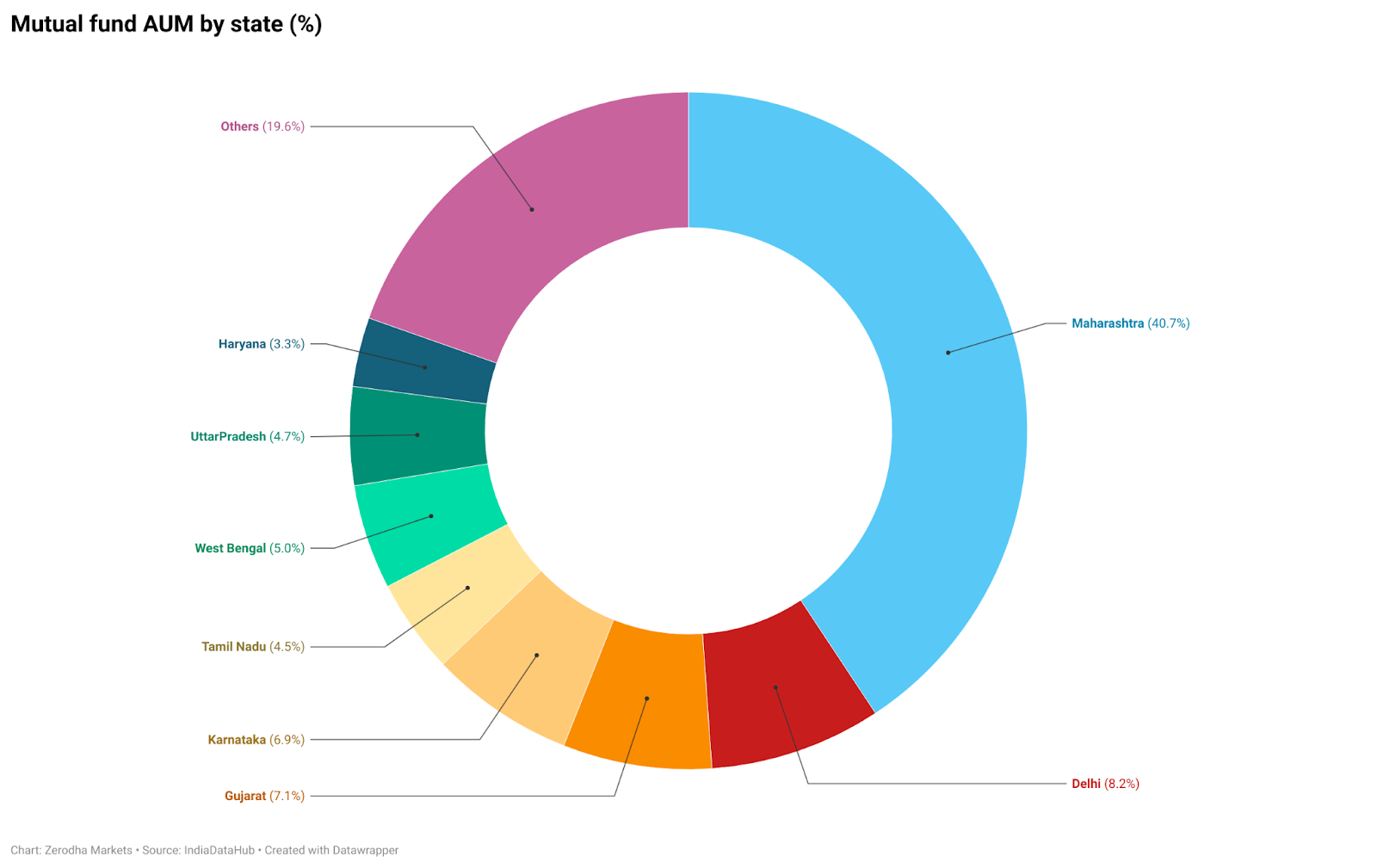

But some states are more keen on mutual funds than others. Here’s a state-wise breakdown of the mutual fund AUM:

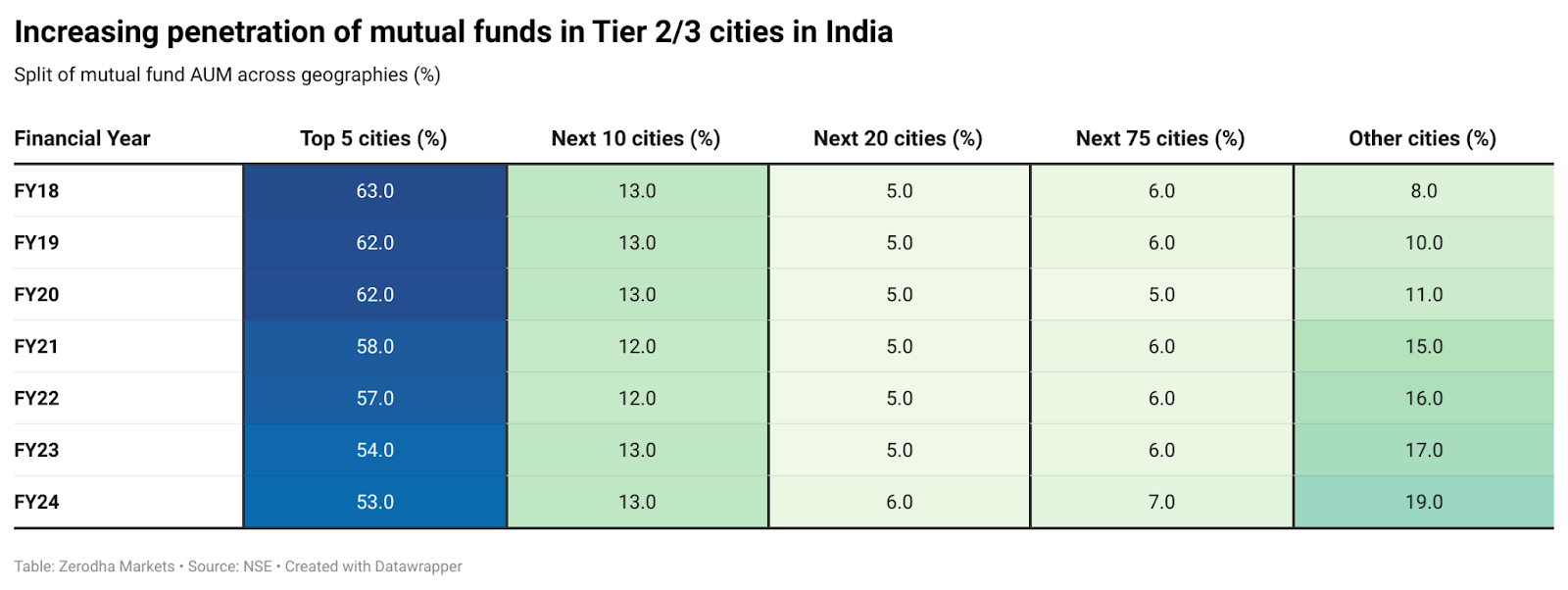

However slowly, mutual funds are seeing increasing participation beyond the top 5 cities.

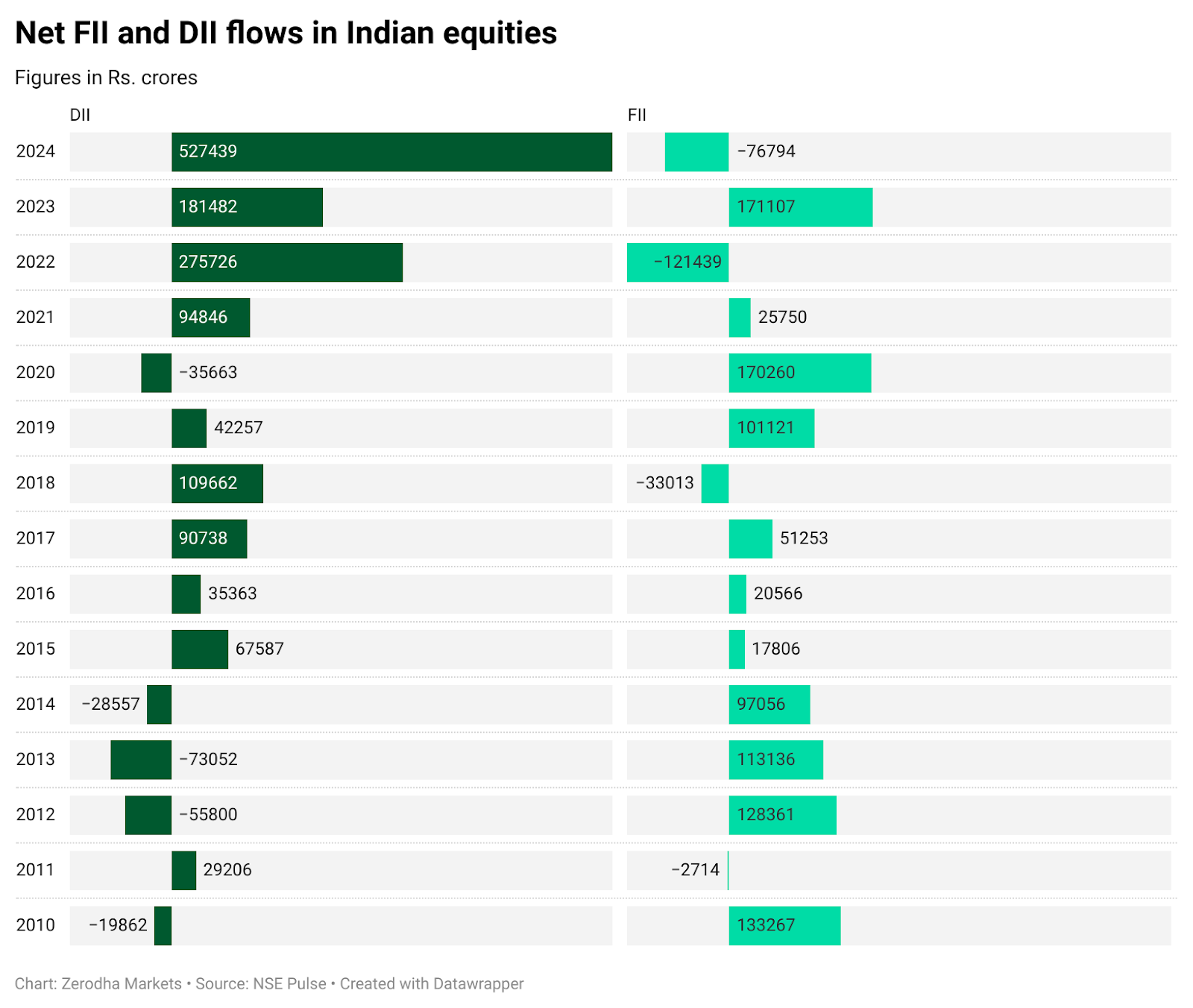

FII vs DII flows

FII flows into India have been volatile — especially of late. DII flows, on the other hand, have remained remarkably stable.

Some people see this as a sign of national superiority. An entire cottage industry of commentators, hungry for social media likes, have spun this into a narrative about how we no longer need foreign investors. That’s dumb. This is a market, not a cricket team. The whole point of a market is to bring many different people together to trade for whatever they need. But I digress…

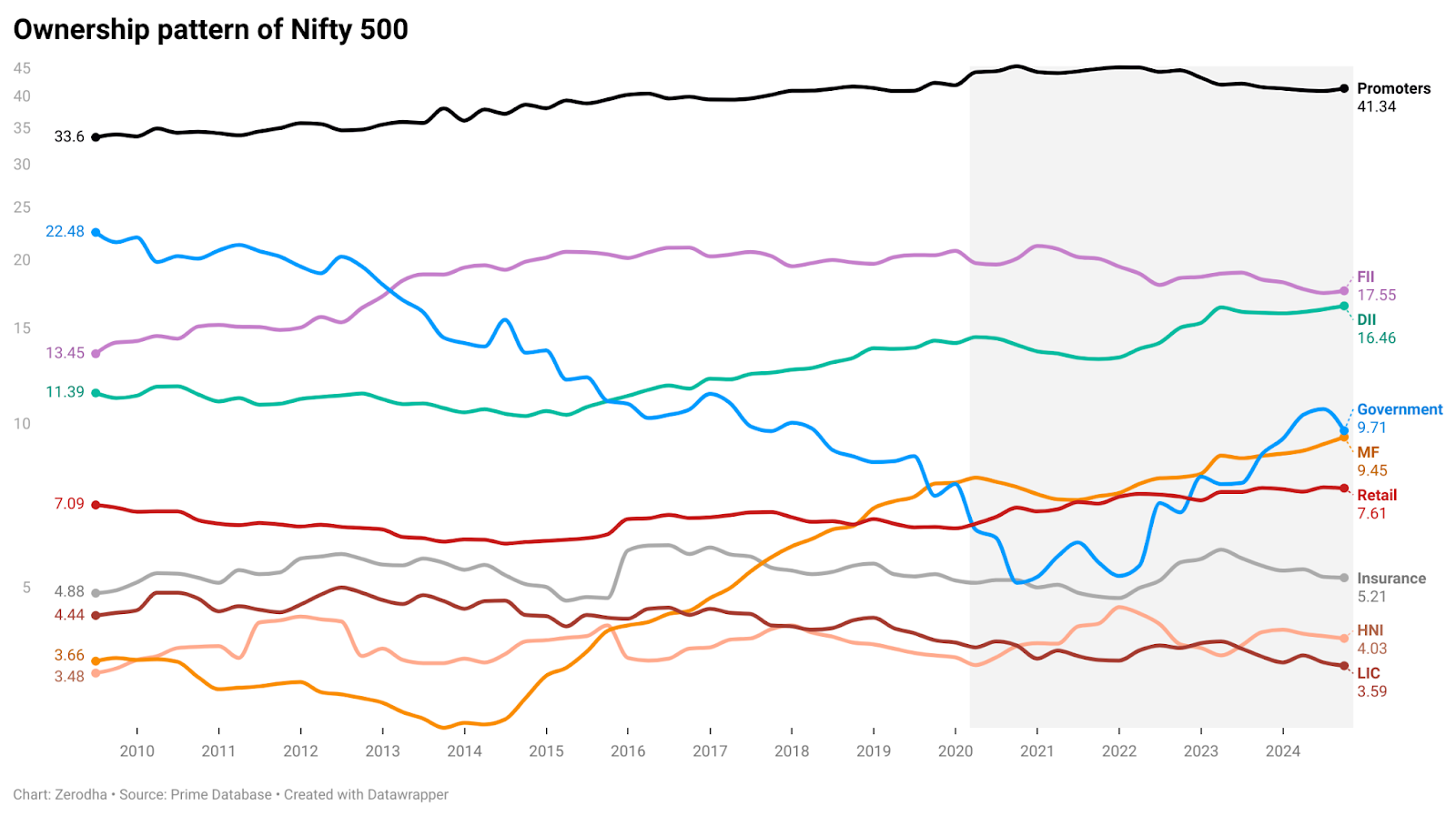

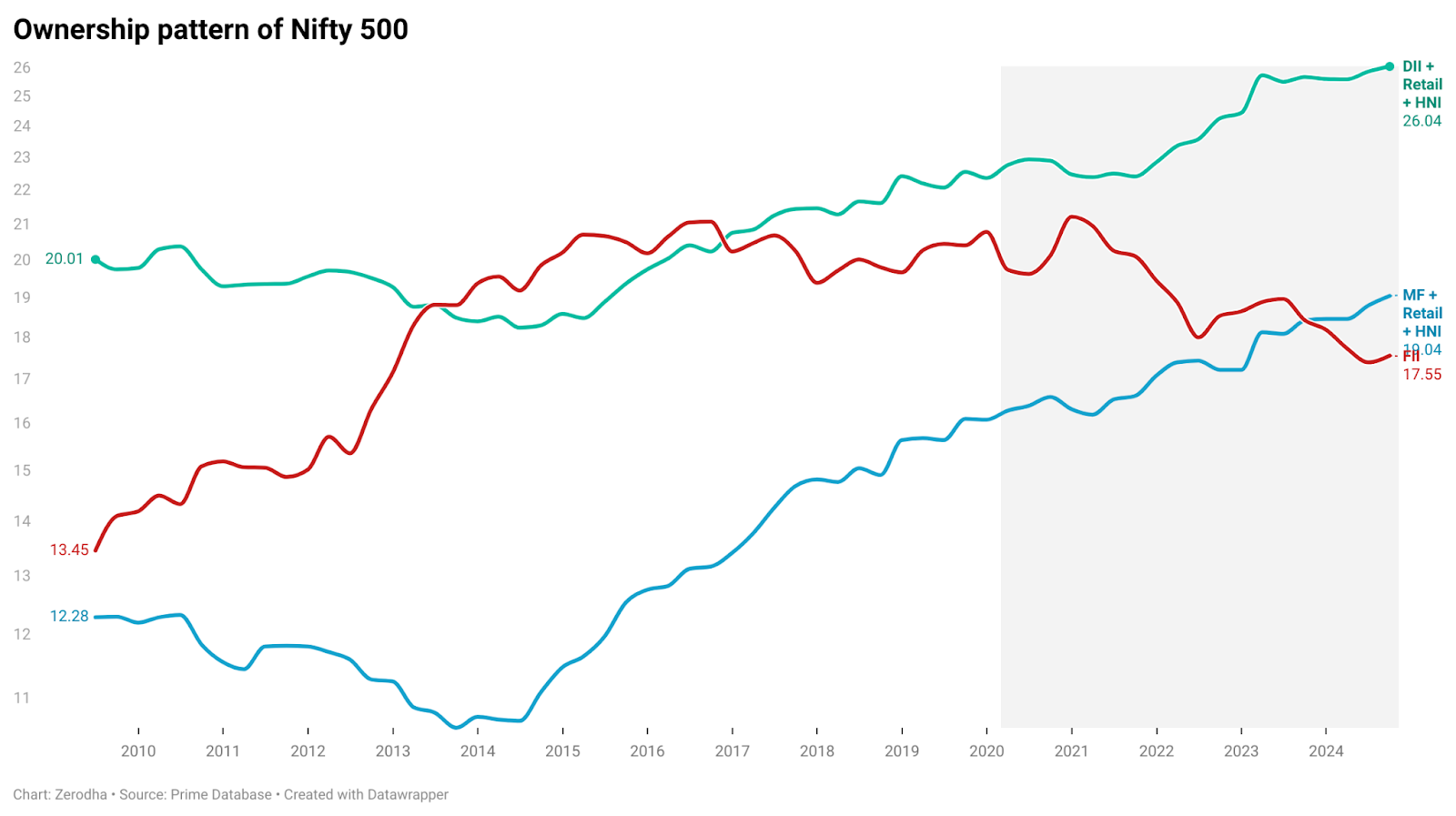

The interesting thing, though, is that DIIs have indeed become a major part of the Indian stock market. These DIIs — institutions like mutual funds and insurance companies — now own ~16% of Nifty 500 companies. Meanwhile, retail investors hold 7.6%. This chart should tell you more:

When you break this chart down further, the dramatic shift of Indian households’ wealth into mutual funds becomes even more stark.

IPO hungama

Ah, IPOs. Ever since COVID-19 hit, people can’t get enough of them.

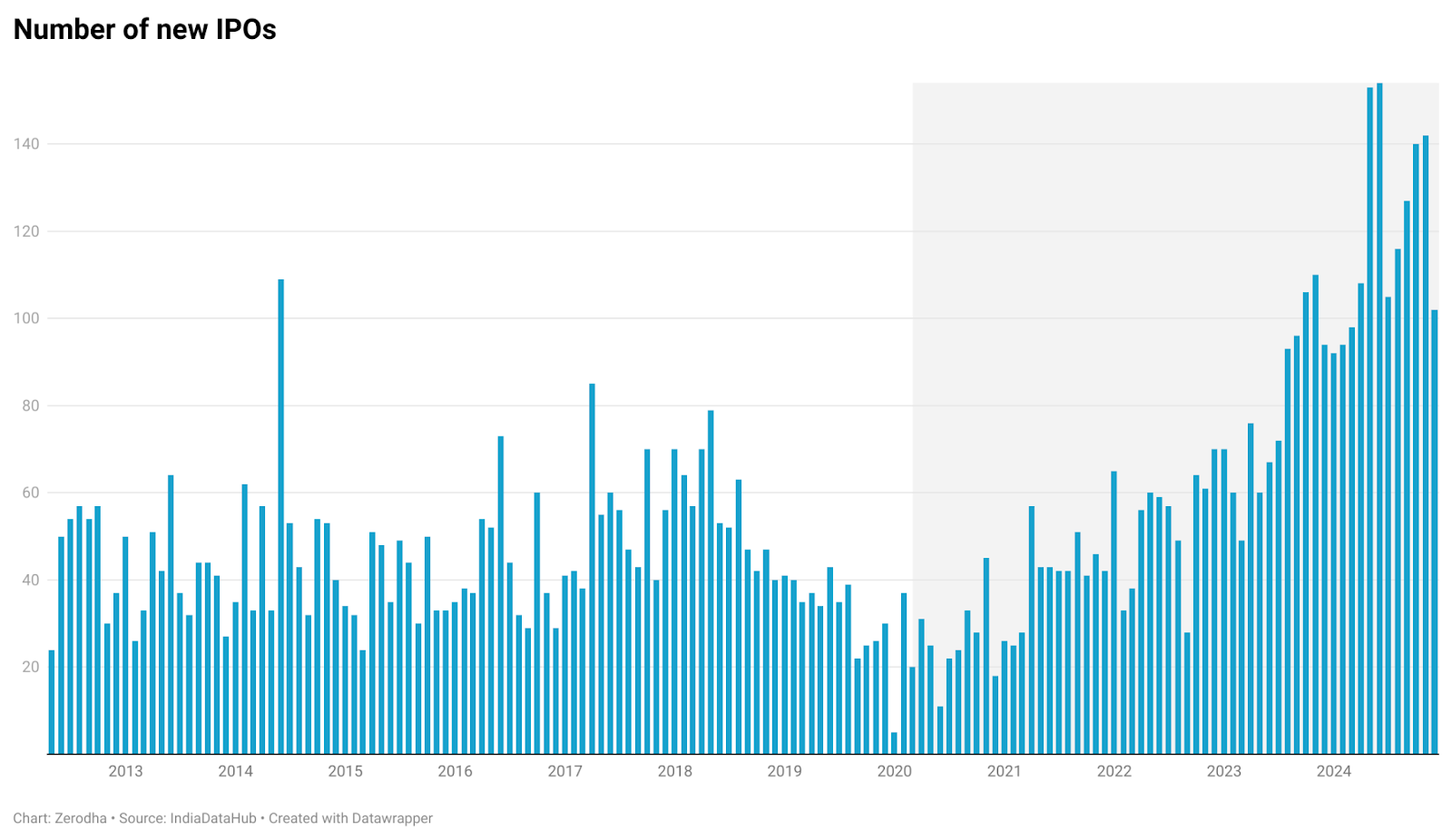

Before COVID, the number of IPOs had been steadily declining since 2017. And that made sense — it was in line with the broader bear market in mid-and small-cap stocks. But after COVID, IPOs went ballistic. We went from ~40-50 IPOs, on average, to more than 100 a month!

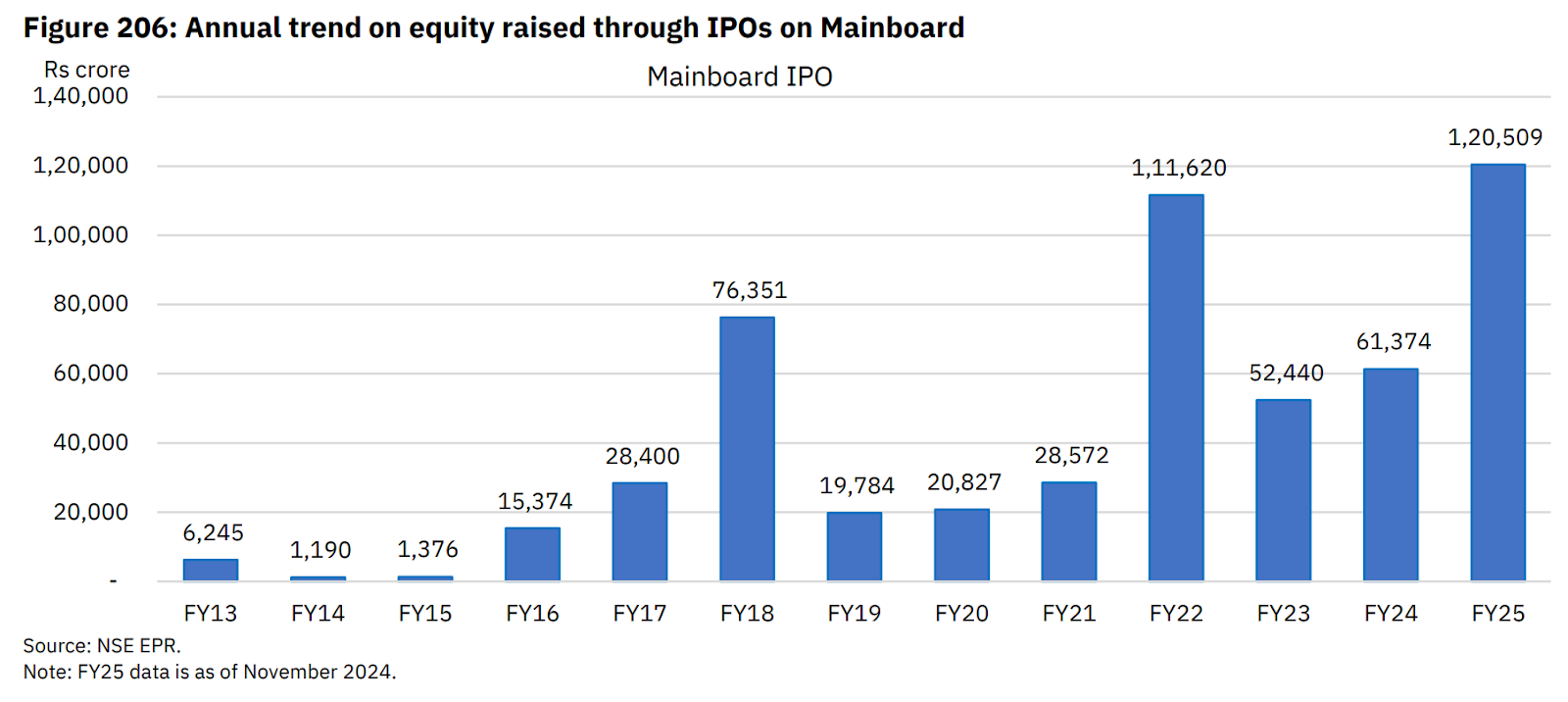

That meant a lot of new entrants to the markets raised a whole lot of money. Before COVID, companies were raising Rs. 20,000 crores per year, on average. Now, they’re raking in many multiples of that amount.

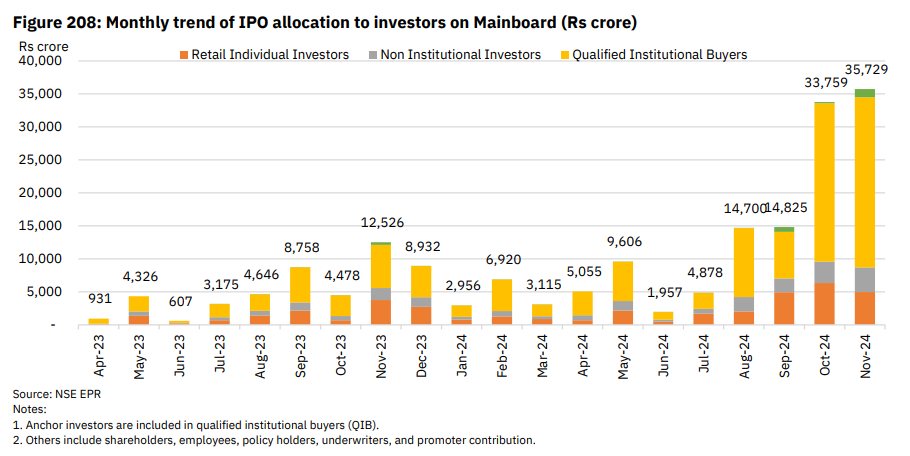

IPOs came with the promise of listing gains. And that drew in many, many retail investors. Look at the share of retail allocation. That might look small, but remember: if a company looks really sound, only 35% of an IPO is reserved for retail. If it doesn’t, that shrinks even further, to 10%.

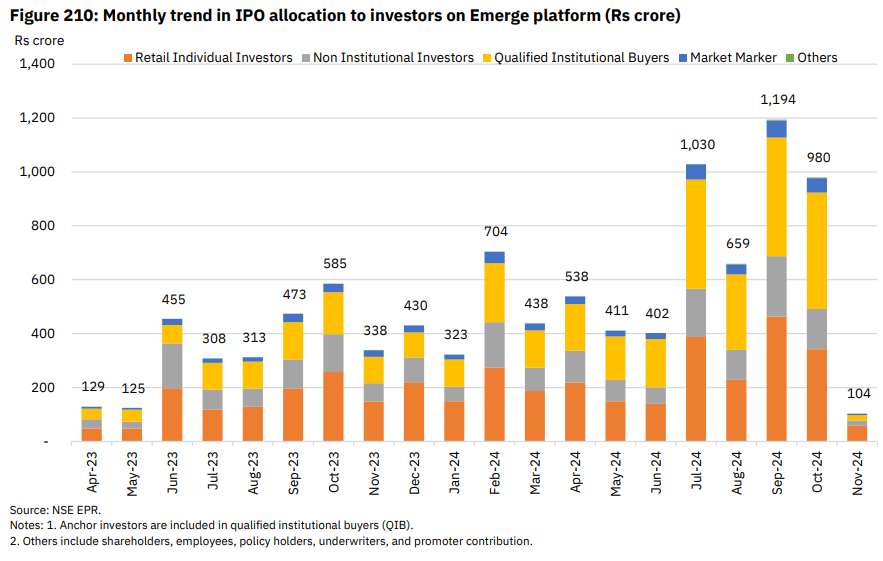

Retail investors featured even more prominently in SME IPOs, of all things:

The dawn of equity culture in India

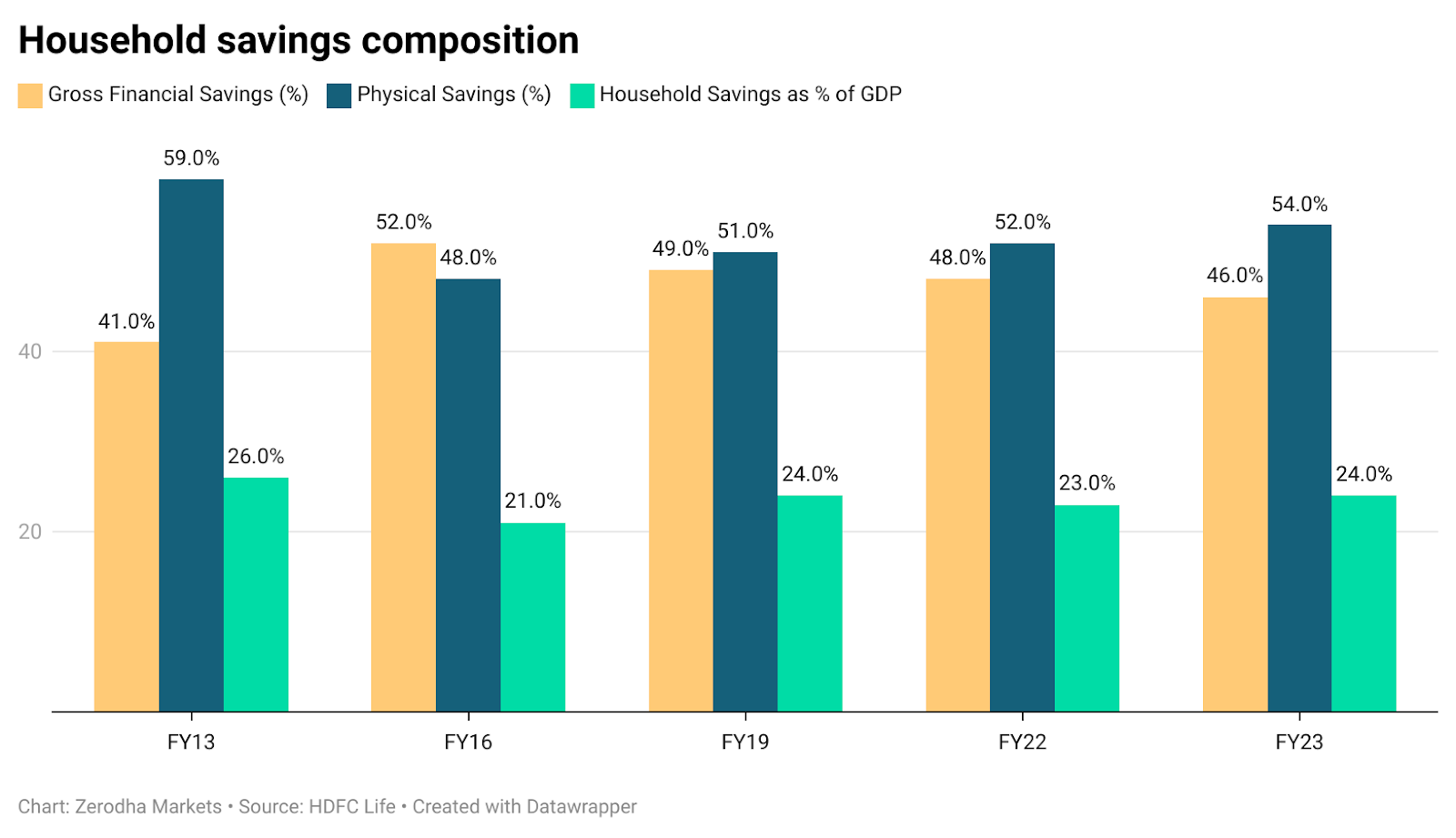

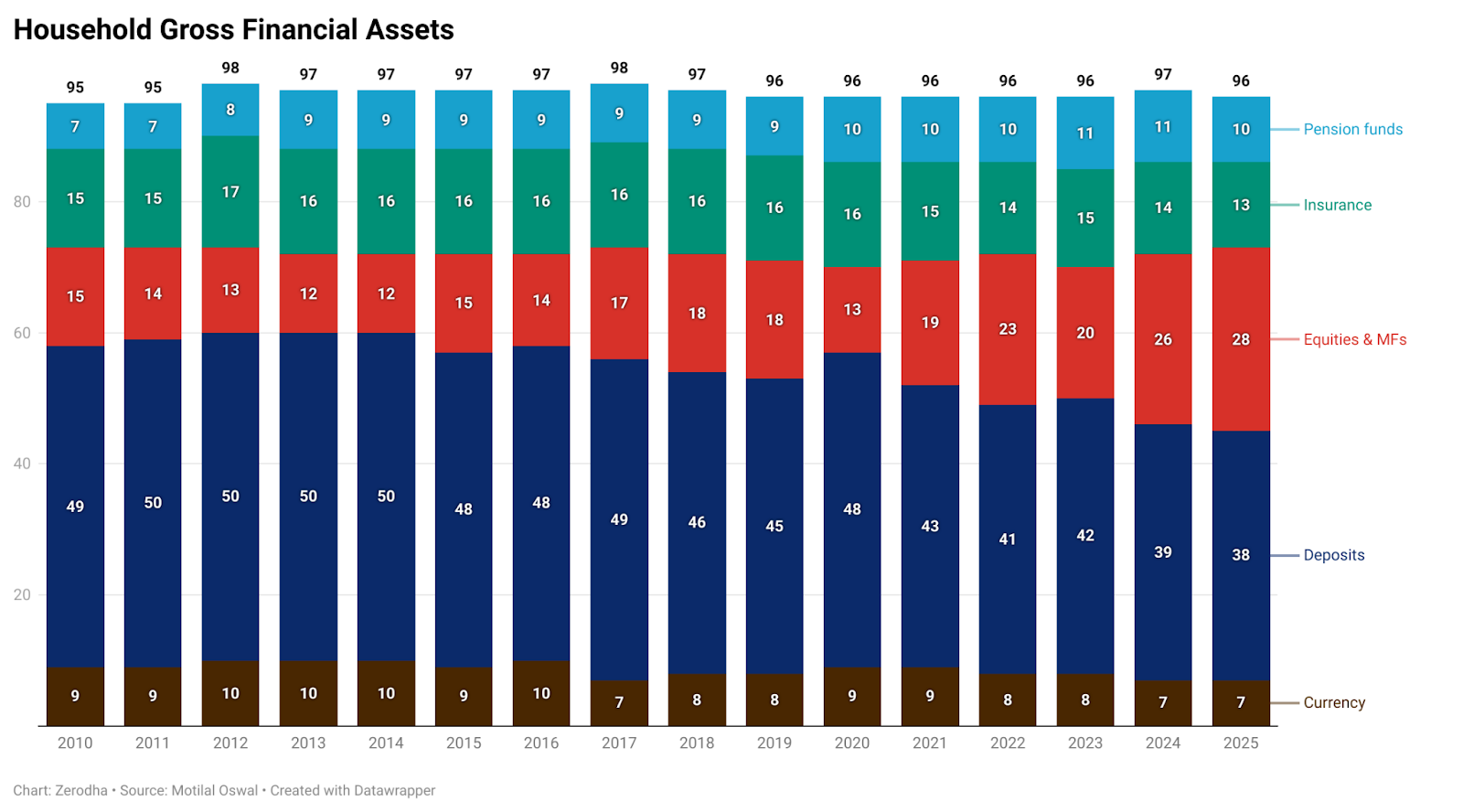

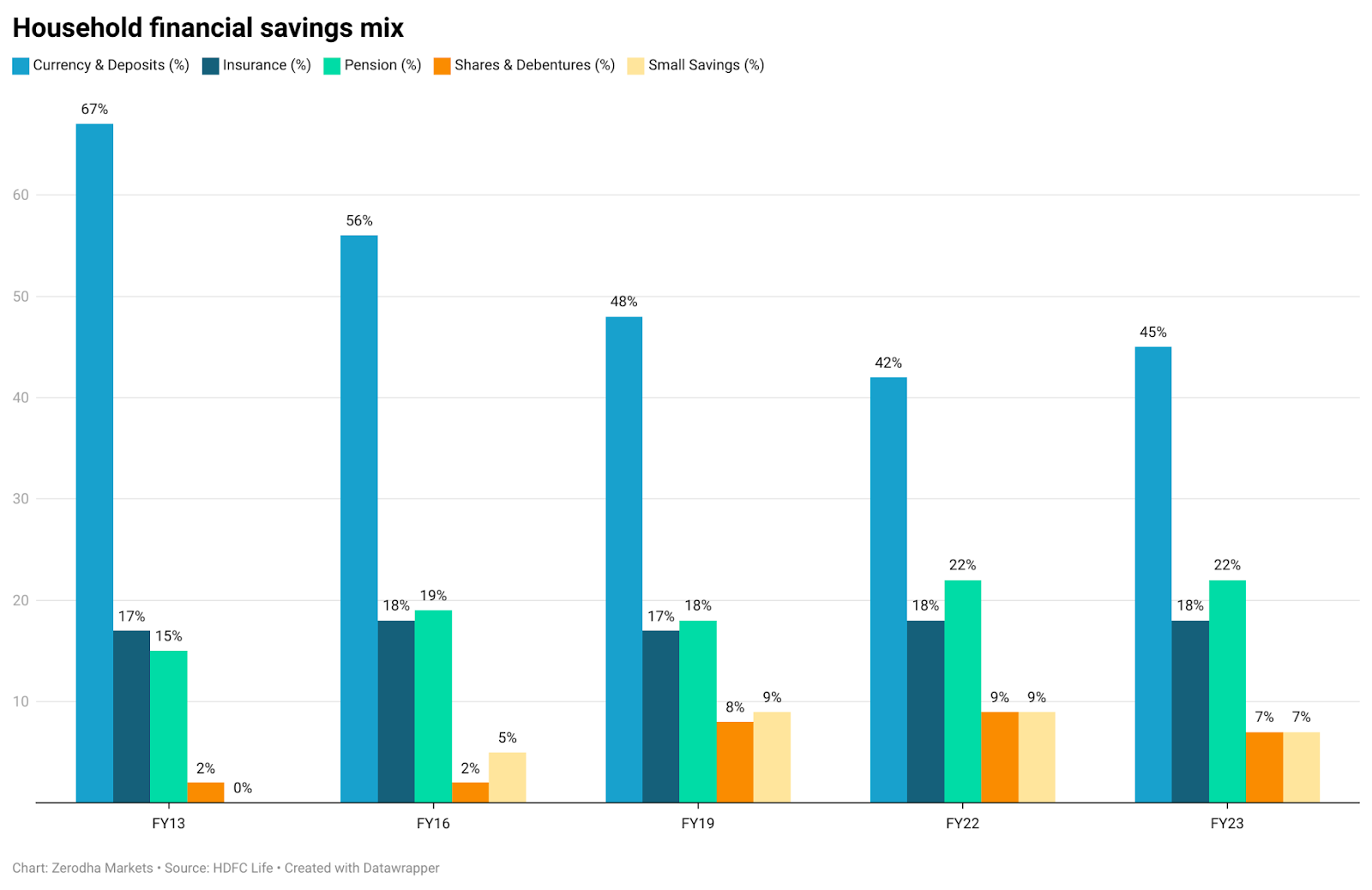

A major mega-trend, post-COVID, is that people are distinctly moving away from storing their wealth in bank deposits.

A good chunk of this money has flown into financial assets, like stocks and mutual funds. A lot more of it has gone into physical assets, like gold and real estate. But hey, you take all the wins you get.

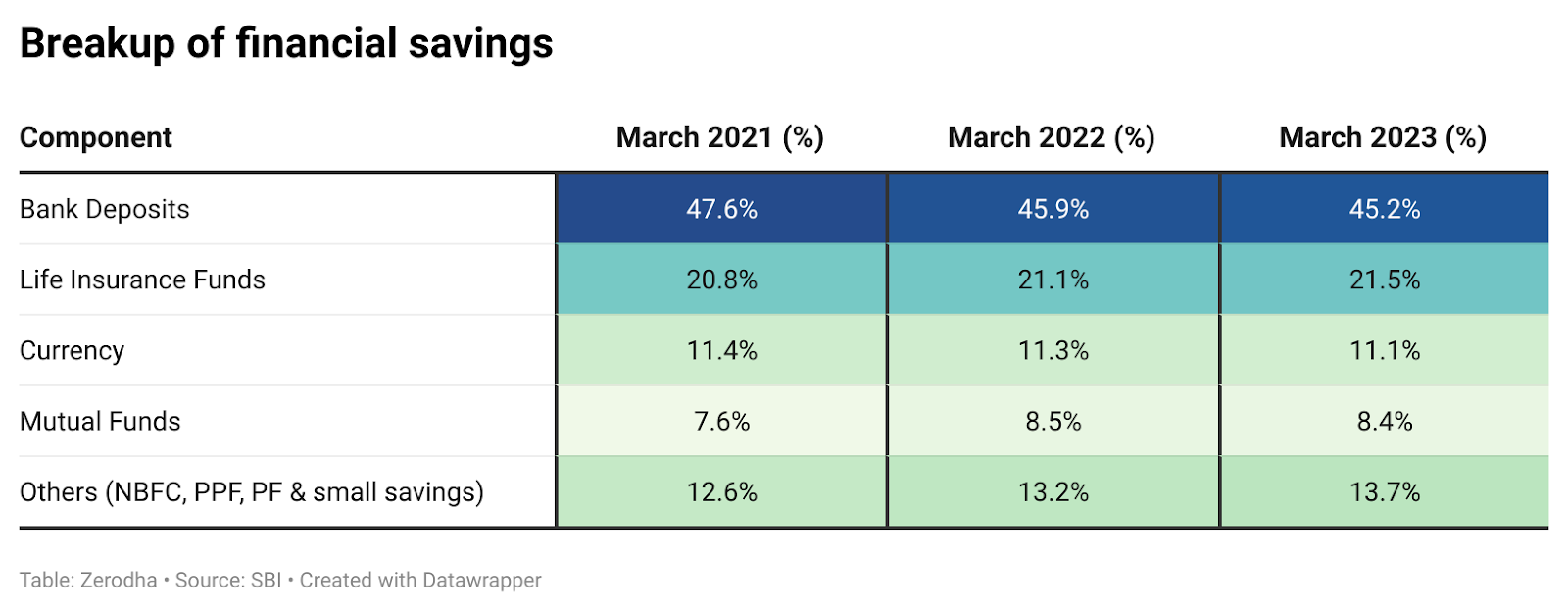

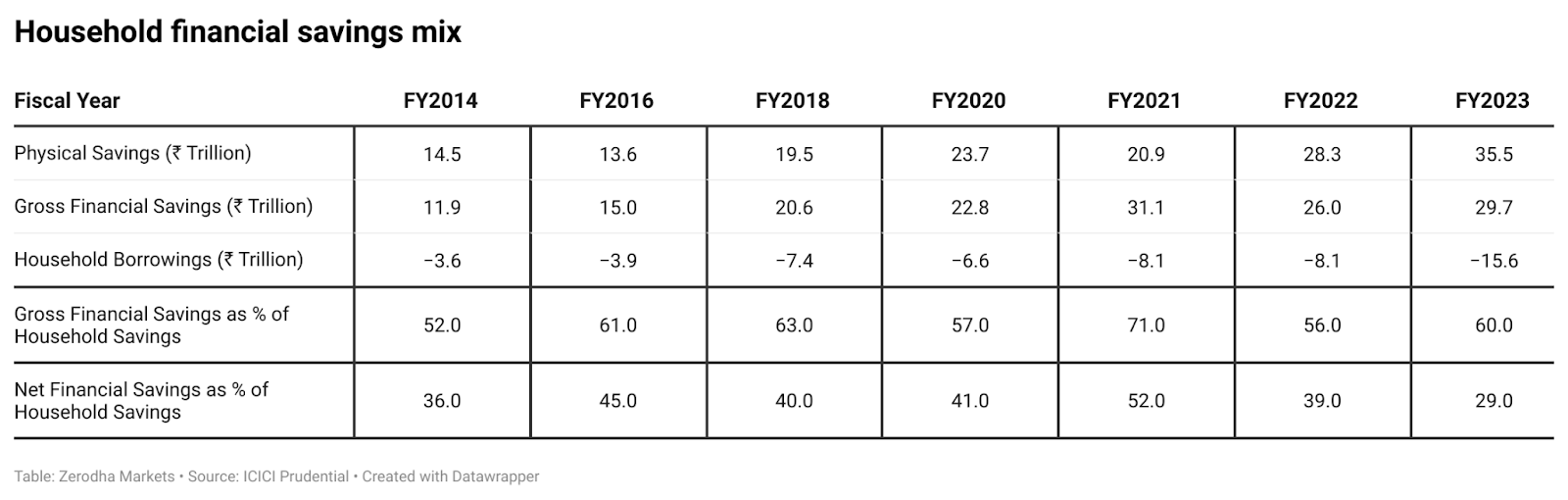

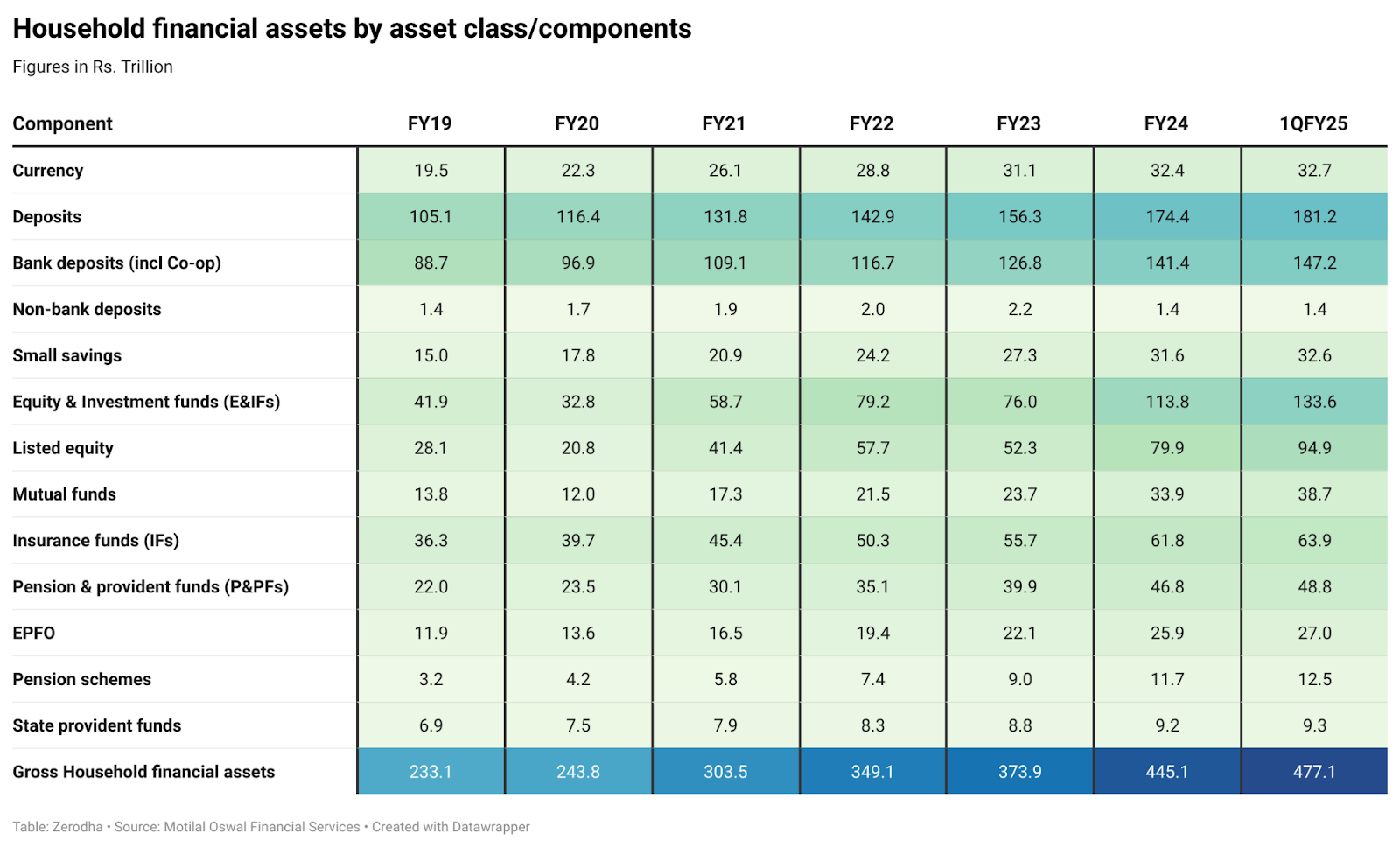

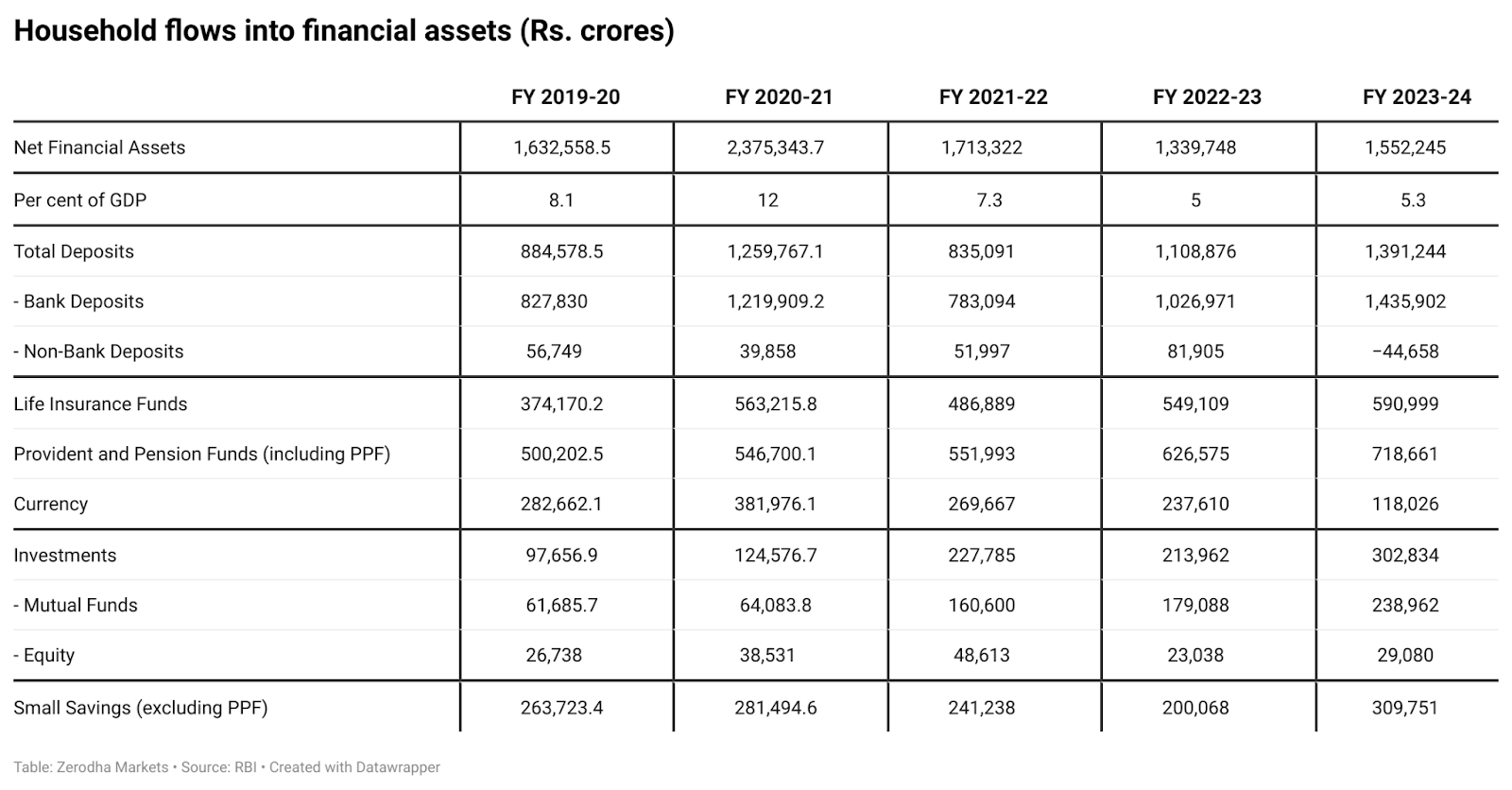

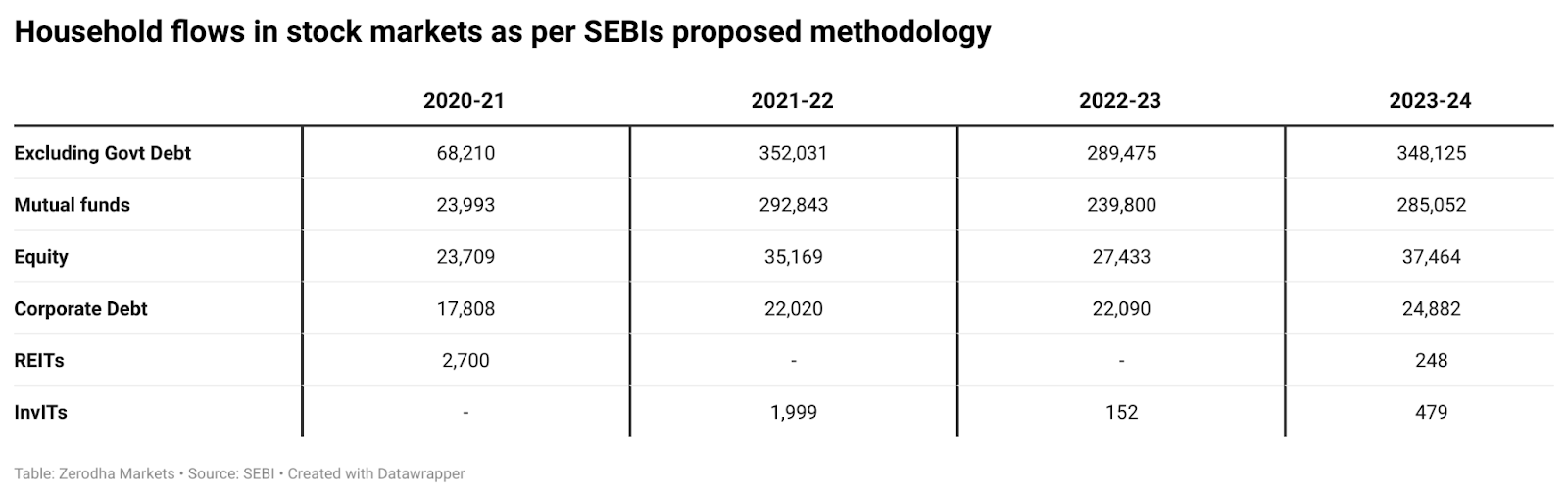

When you only look at financial savings, this becomes extremely stark. There has been a noticeable shift away from bank deposits to equities and equity mutual funds. The data on household assets, sadly, is terrible. But we’ve tried collating data from a bunch of sources:

Parting thoughts

Congratulations on getting through this mountain of charts. But with these out of the way, it’s worth reflecting on what they mean, taken as a whole.

The years after COVID saw a Cambrian explosion in our markets. The ingredients for this explosion had been coming together for a while, even before the pandemic struck. India had just taken to digital tools in a big way, and its digital public infrastructure greatly simplified financial inclusion.

But that wasn’t enough. In a normal world, bringing people to the markets may still have been a long slog, as they slowly came around, one by one, to see investing as a smart use of their savings. But that process was suddenly accelerated by the pandemic.

More than anything, this became a time of rapid change.

Under the cover of a market that has now stayed benign for almost a decade, millions of people have rushed into the markets. A lot of them are young; a lot of them are stupid. And they’re trying their hands at anything they can. They’re flipping IPOs. They’re pumping money into penny stocks. They’re taking leveraged bets on options. There is a frenzy of activity right now, that’s wholly greater than anything we have ever seen before.

It’s easy to bemoan all the stupidity, as many “experts” are currently doing. But you can’t lecture someone into wisdom. People get irrationally optimistic during bull markets and make poor decisions. When bear markets come around, they get hurt. Hopefully, they learn something from those mistakes, and become better investors. This is how the markets have always worked. Nobody can wish it away.

But look at the other side. Even as some are making dumb mistakes, others are learning to be smart with their money. They’re moving from low-yielding bank products to equities. They’re trying to understand how businesses and industries work. They’re investing in direct mutual funds, and maintaining SIPs. Securities have entered everyday conversations. Indian financial markets are quickly becoming deeper and more liquid than they have ever been. In the long run, this is terrific news.

Speculation and investing always go together.

Sadly, a wild period of change can’t last forever. Every year cannot bring another exponential growth in investors, flows, or activity. The flux will eventually end, and at some point, we’ll hit a new equilibrium. It’s hard to know when, or how (or I’d be a billionaire). Maybe it’s already happening. And the end need not be pleasant.

We’re in an interregnum — we’re in the chaotic interval between two periods of normalcy.

To quote Antonio Gramsci, “The old world is dying and the new world struggles to be born. Now is the time of monsters.”

I am excited, and terrified, of whatever comes next.

While I wrote most of the post, the beautiful ending is by my colleague Pranav who’s a phenomenal writer. Also, the data disclosures about Indian markets are terrible, and I have to thank my wonderful colleagues Shubham and Meher for all the pointless hours they spent being data coolies 😬

Waiting for ur next article

Hi Bhuvan. It is eye opening article for all. Where our new generation is exploring the financial opportunities. It is not only Bank/Post office, Gold or Property where our old generation always believe. It is the time of investing in MF or Equity or IPO where numerous opportunities exist. Thanx for highlighting in details in this Article. Thanx once again to you and your entire team for this hard work.

Very well researched and a beatifully written long form article! Would love to read more such in the future. Well done! 🙂

what a profound article on the transformation journey of the Indian stock market and its advancements

Hey Bhuvan!! great job team.Overwhelmed with data although. Would love to read summary of some of the analysis.

Not sure how much time you guys put in to write this, this was soo informative and insightful thankyou, Please keep up the good work Team (❤)