You have to get punched in the face to know how it feels

I’ve never seen a market phase crazier than the everything rally after the pandemic. Excluding long duration bonds, you would’ve made money no matter what you bought, including the most speculative garbage. In fact, it would’ve taken a special kind of genius to lose money in the last 4-5 years. The sheer speculative mania is one for the history books.

Look at the calendar year returns for 2020 and 2021. They’re nuts. And remember, when the pandemic hit in early 2020, Nifty 50 was down by 38%, S&P 500 by 34% and Nasdaq 100 by 28%. Yet, when the year closed, each of them were up by double digits. Things were so crazy that it felt like everything would end badly, and soon.

| Year | Nifty 50 | S&P 500 | Nasdaq 100 |

| 2019 | 12.02% | 28.88% | 37.96% |

| 2020 | 14.90% | 16.26% | 47.58% |

| 2021 | 24.12% | 26.89% | 26.63% |

| 2022 | 4.33% | -19.44% | -32.97% |

| 2023 | 20.03% | 24.23% | 53.81% |

| 2024 | 5.69% | 11.26% | 11.17% |

The party paused briefly in 2022, when inflation spiked globally due to the after-effects of the pandemic and central banks hiked interest rates in response.

When the markets fell that year, I thought the “generational detox” was finally here. After 2020, a new generation of investors had entered the markets. Like the generation before them, they were doing all the dumb things, but on steroids, cocaine, and ecstasy. I assumed the bear market would last for a while, and would detoxify these newbie investors from all the stupid things they were doing.

I was wrong.

The markets bounced back with a vengeance in 2023, erasing all the losses of 2022. Even as I write, equities are at lifetime highs. Many people, including myself, had assumed that the madness in the markets was a zero interest phenomenon. We were all wrong.

Despite high interest rates and sticky inflation in both India and the US, we’re seeing a speculative fervour similar to what we saw in 2020-21. Crypto has almost fully recovered. People are back to paying hundreds of thousands of dollars for pictures of monkeys. Trading volumes in junk stocks, crypto, monkey picture, and options are almost at the levels we saw in 2021. It’s an upside-down market.

The generational detox has been postponed.

I still think a serious detox — a mental enema if you will — is due. Mind you, I am not predicting an imminent crash — I’m no astrologer. But a serious market crash or two is more-or-less guaranteed in an investor’s lifetime. When it happens, investors will learn a lot about themselves. I know I sound like an old man yelling at clouds, but hear me out.

Man is not a rational animal but an extrapolating animal

We tend to anchor ourselves to market conditions from when we start investing, and then extrapolate the future. If markets go up for extended periods of time, our risk perception warps. If one starts investing in a raging bull market, one tends to assume markets will always go to the moon. One then does stupid things like making 100% equity portfolios, ignoring diversification, or assuming that making money in the markets is easy.

If one starts investing during a bear market, one tends to assume that the markets are going to hell. One tends to become excessively conservative, have little or no equity exposure, and develop an overly pessimistic view of the markets and the economy.

Excess optimism is like plaque, it tends to build up over time and grows over common sense. Excess pessimism is like acid, it corrodes critical thinking. You need a balance between both.

A bear market in the early stages of your investing journey is one of the best things that can happen to you, though, because you learn your lessons right at the start. Bear markets detoxify. The odds of you making dumb mistakes afterwards are lower. Bull markets, on the other hand, can be dangerous. Extended periods of rising markets lull us into a false sense of comfort. The good times shall last forever, we imagine.

I am not saying this because markets are doing well right now. Although most investors, including me, have an annoying habit of expecting the worst when everything is going well, what the data shows is the opposite. All time highs lead to more all-time highs.

But things won’t always look like this. During bull markets, investors get carried away and do things they’ll regret in bear markets. This post is a reminder to not get carried away. You should invest in a way that you’ll have the least amount of regret in both bull markets and bear markets.

Everything is cyclical

I think it’s essential to remember that just about everything is cyclical. There’s little I’m certain of, but these things are true: Cycles always prevail eventually. Nothing goes in one direction forever. Trees don’t grow to the sky. Few things go to zero. And there’s little that’s as dangerous for investor health as insistence on extrapolating today’s events into the future.

The economy will not rise forever. Industrial trends won’t continue indefinitely. The companies that succeed for a while often will cease to do so. Company profits won’t increase without limitation. Investor psychology won’t go in one direction forever, and thus neither will security prices. An investment style that does best (or worst) in one period is unlikely to do so again in the next.

— Howard Marks

It’s important to remember that most things in life are cyclical. That’s how you make peace with the fact that there are some things that you can’t control, only deal with. Remembering this is all the more important in the markets, where very little is in your control. Times change, tides change, and so do the markets. If you make sure this is burnt into your brain with a flaming hot branding iron, you’ll have a moderate shot at a peaceful investing journey.

Successful investors have the magical ability to stay serene no matter what. Having the ability to say “this too shall pass,” both at the peaks of exuberance and the depths of despair is important in investing. Seasoned investors are calm because they’ve internalized the fact that the markets are unpredictable, and thus stick to what they do best.

For well over a decade, we’ve been on the good side of the cycle. But good times don’t last forever. If you’re lucky enough to be in a stable country like India, the odds of extreme tail-events like total economic collapse, deflationary bubbles, or hyperinflation are low, though not zero. Nevertheless, you have to ensure that you build a portfolio that has a reasonable chance of surviving most probable scenarios.

Bad things doth happen, and happeneth again

The ancient Stoics had an exercise called premeditatio malorum, or negative visualization. They would deliberately visualise a range of bad events, including death, so that they could deal with them with equanimity when they came. I think investors should read market history for the same reason.

“Only a fool learns from his own mistakes. The wise man learns from the mistakes of others.”

― Otto von Bismarck

Knowing a little market history helps you understand the range of possibilities. Of course, it won’t lessen the pain of losing money in a bear market, or prepare you for one. But it’ll help you be less surprised.

Meb Faber: “The only black swans are the history you haven’t read.” What do you mean by that?

William Bernstein: Well, what I mean is that the more history you read, the less you will be surprised. When someone calls something a black swan, what that almost invariably tells me is they haven’t read enough history. But it’s true throughout all of not just financial history, but geopolitical history. There is almost nothing new under the sun.

(Link)

If you’re going to retire 30-40 years from today, it’s guaranteed that you will see one or two bad crashes in your earning life. By bad, I mean something like 2008, when BSE Sensex fell 60%, the BSE S&P Midcap index fell by 72% and BSE S&P Smallcap index fell by 77%.

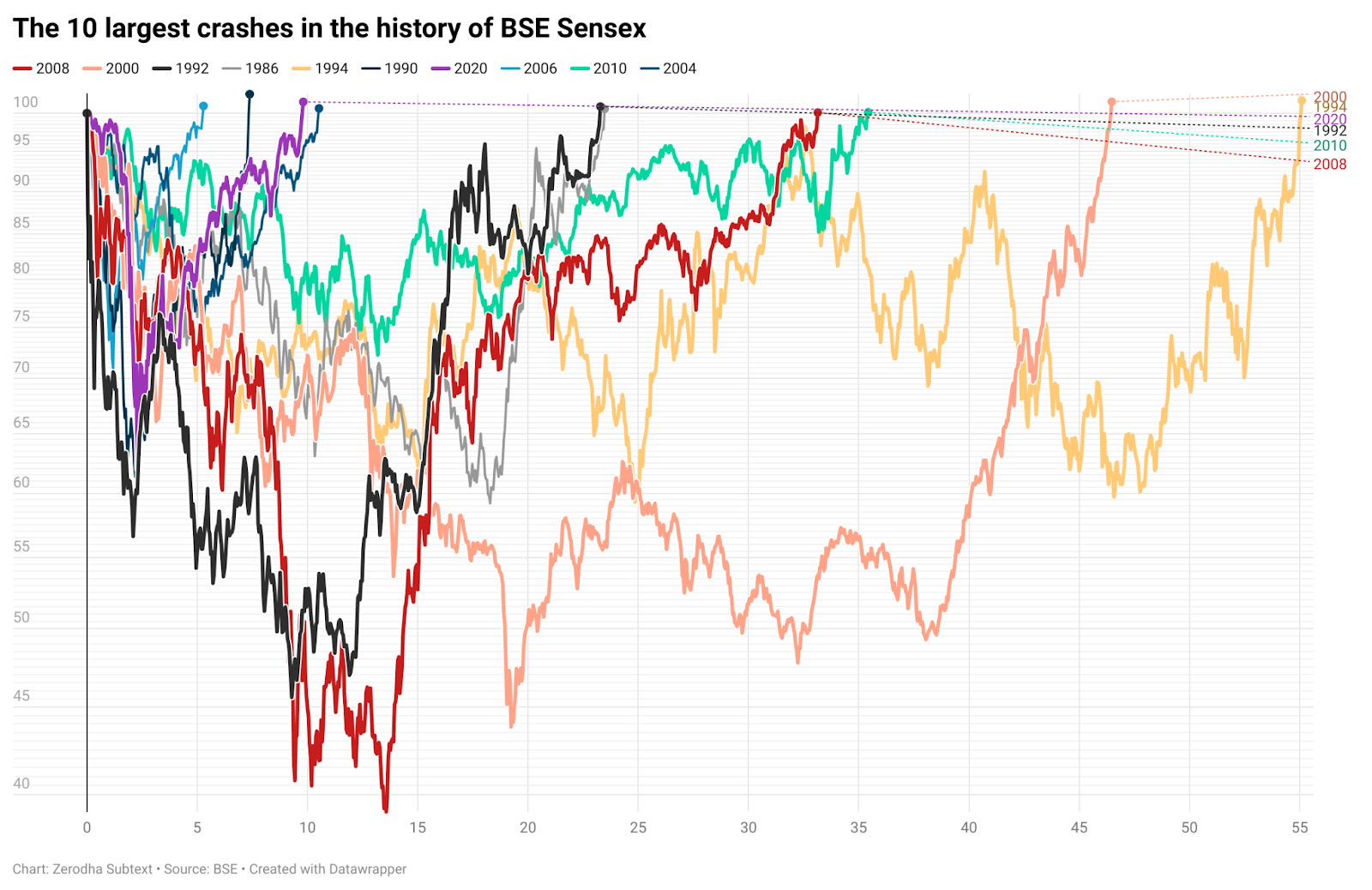

It can be worse still. While 2008 was the worst the markets have fallen, the size of a drawdown isn’t all that matters. Sometimes, crashes continue for months at an end. In 1994, 2000 and 2010, the crashes weren’t deep but lasted longer, as you can see from the months they took to recover:

And if you think this is bad, you ain’t seen nothing yet.

The BSE S&P Sensex is the oldest index we have. It starts from 1986, with backdated data from 1979. So we have just 38 years of data. Just 2-3 market cycles. That’s nothing in the grand scheme of things. Also, since 2010, we’ve been blessed with unusually calm markets without any serious corrections.

Of course, we’ve had some 20-30% falls, but these have been mere blips, with the markets recovering quickly. We haven’t had a prolonged market crash that was triggered by a serious economic event, like the 2008 global financial crisis. Check out the depth of drawdowns before and 2010 — the last fourteen years have been a smooth upward journey. Even COVID, which was supposed to kill us all, feels like a nothing-burger in hindsight.

Two generations of investors have been conditioned into thinking that making money in the markets is easy. While the history of Indian markets is short, the US markets have a longer history, and can give us a sense of how markets perform over long periods.

The Great Depression stands out — both, in terms of depth and time taken for recovery. The markets ground down for almost 3 years, and the recovery then took 12 more years. That’s brutal. The 2000 tech bubble and 2008 global financial crisis are the next worst drawdowns.

Here are some of the worst drawdowns of the S&P 500 since 1870:

There were also long periods in history where stocks underperformed bonds:

- From 1929 to 1943, the S&P 500 underperformed 3-month T-bills for 15 years.

- From 1966 to 1982, the S&P 500 underperformed 3-month T-bills again for 17 years, although the margin was close.

- From 2000 to 2012, the S&P 500 underperformed both 3-month T-bills and the 10-year Treasury bond.

That’s rough.

Maybe you think I’m cherry-picking dates. Sure. But you should think of this in terms of sequence risk. In other words, no matter how the markets otherwise perform, your retirement could come at a time when equity returns are bad.

Equities often perform poorly despite there being no crash. In some ways, crashes are easier to deal with than long periods when equities under-perform, because they tend to be shorter.

Equities in emerging markets (EM), for instance, have been underperforming developed markets (represented below by the US) for over a decade. And it’s not just because China is the largest country inside the MSCI Emerging Markets (EM) index. The performance of MSCI EM and MSCI EM Ex-China after the 2008 crisis is indistinguishable. The biggest reason for the underperformance is the strength of the dollar.

Another example of a long period of equity underperformance is China. Since inception in 1993, MSCI China index has generated 0% returns, compared to MSCI India which has generated annual returns of about 7.5%, MSCI Emerging Markets 6.5%, and MSCI ACWI 8.3%, all in the same period. The biggest reason is the high rate of equity dilution, which reduced the earnings per share.

Let me show you something even more scary.

Many years ago, Bridgewater published a study on the benefits of geographical diversification. They looked at how investors fare when investing only in a single country, compared to a simple equal-weight portfolio that invests in multiple countries. Many individual countries had horrible market phases. In Russia, Germany, and Korea, investors were wiped out completely. Only if investors had diversified across countries would they have come out alright.

You might say this is no longer possible; the world has dramatically changed since the early 1900s, with the creation of central banks and securities regulators, the end of the gold standard, the opening up of capital accounts, the rise of institutional investors, and much more. In summary, you could call me an idiot.

Fair.

But let me quote Frey, who worked with Jim Simmons at Renaissance:

You know, if you’re looking at the 1800s, you didn’t have a central bank, really. […] When I start here, it’s really pre-Industrial Revolution. Now, we’re looking at the Modern Age […] We have high-frequency trading, we have a central bank, we have all sorts of interventions in the market. But I’m going to show here that, at least in one important measure, the market hasn’t changed much in those 180 years. And it’s a measure that’s, I think, very relevant from a risk point of view. It’s looking at […] maximum drawdown.

Everything changes in the markets, but the one constant is risk. The reasons for a crash can change, but markets still keep crashing.

You can’t read about pain, you gotta feel it

“Who is the happier man, he who has braved the storm of life and lived, or he who has stayed securely on shore and merely existed?”

— Hunter S. Thompson

No amount of reading will help you understand what it feels like to live through a horrible bear market like the 2008 crisis, the 2000 dot-com bust, or, god forbid, the Great Depression. You just have to live through one and experience it yourself.

This reminds me of something William Bernstein, the author of several financial classics, said on a podcast:

“There is a wonderful quote from Fred Schwed’s marvelous book, Where Are the Customers’ Yachts? And I’ll read it. And here’s the quote, “There are certain things that cannot be adequately explained to a virgin, either by words or pictures, nor can any description I might offer here even approximate what it feels like to lose a real chunk of money that you used to own. If you’re a young investor, you’re an investment virgin, you’ve never lost a real chunk of money, and you have no idea how you’re actually going to respond to stocks falling by 30% or 50%.“

Here’s something Morgan Housel said in response to a question about quoting Buffet’s line of “Be Fearful When Others Are Greedy and Greedy When Others Are Fearful” and actually following it:

“Now, when the economy and the stock market are pretty strong and prosperous, if I said, “Clay, how would you feel if the market fell 30%?” most people would say, “Uh, I’d view that as an opportunity. That’d be great. The stocks that I love would be cheaper. It’d be a buying opportunity. That’d be great.” Okay, and for some people, that really is the case.

But then if I said, “Hey Clay, the market falls 30% because there’s a pandemic that might kill you and your family, and your kids’ school is shut down, and you have to work from home, and the government’s a mess, it’s going to run a six trillion dollar deficit to try to figure this out.” How do you feel in that situation? You might be like most people who will say, “Oh, in that world,” or once they experience that world, it feels very different.

Or if I said, “Hey, the market fell 30% because there was a terrorist attack on 9/11, and all the experts think that that was just scratching the surface of what’s to come.” Do you feel bullish now? A lot of people will say no, they don’t feel so bullish.

Once you add in the context of why the market fell, most people will realize that it’s much easier to quote Buffett than it is to actually be somebody like Buffett.”

I can attest to this feeling. In 2020, when it felt like the world was ending, I had some spare cash. And even though I wasn’t panicking, I was too scared to invest. It really did feel like the world was ending. I knew all the theoretical explanations: bear markets are temporary, you have to take a long-term view, asset allocation is important blah blah. But when it came to pulling the trigger, I was scared. By the way, despite my fear, I kept investing, and thanks to that, I look like a bloody genius now.

Here’s something Cullen Roche, one of my favorite financial writers, said:

And so, even in the case of someone like me […] I haven’t been around forever, but I’ve lived through […] three, four pretty big bear markets. That shaped me in a lot of ways, and I’ve seen though the way that, you know, not just a persistent sort of grind like the early 2000s can wear on you.

For people listening. I mean, that was basically three years of the stock market just kind of ticking lower […] every single month basically. And […] you know, it was a grind. […] It was only three years, but it felt like 20 years just because it seemed to never end. And so that was very different though from the financial crisis, where the financial crisis was really, I mean, it was half as long, but it was twice as painful, in large part because, I mean, God, in February, March of 2009, it really felt like the wheels were coming off of the financial system. And it was a really frightening environment in a way that was very different from the more drawn out, prolonged sort of 2002 environment.

Time shrinks in a bull market. Years feel like months. But in a bear market, and I mean a real bear market, time expands. Even a month feels like a year, and the worst bear markets can often last for years.

Brace yourself. Winter is coming (eventually).

Since 2010, we’ve been in an unusual environment of low volatility, barring short episodes of drawdown. This is a chart of Sensex with drawdowns of more than 10% highlighted in red. The post-2010 period has been like a honeymoon.

There could be structural reasons for this low volatility environment: the growth of derivatives, structured products, perceived central puts, dominance of institutional investors, increased flows into passive funds, basket trading and so on. Even a cursory at history, however, shows that stability breeds instability. Periods like the last decade, when markets steadily drift upwards and generate easy returns, are not the norm. Periods of calm are always followed by periods of tumult.

I don’t know when the calm will end. Neither does anyone else. Only two people can predict the market— God and a liar. Investing is a long-term game. If you want to survive both the best and worst periods, you have to build a portfolio that does reasonably well across a wide range of market conditions.

Having said that, you can’t hedge and diversify away all risk. If you could, why would anyone ever go for a bank fixed deposit? You have to take some risks. That’s the price you pay for the probability of a higher return than a fixed deposit. Investors often look in the rearview mirror and think that they should have taken more risk in a bull market and less risk in a bear market. Neither of those frames of thought is right.

This is where learning a little bit of market history can help. History helps you appreciate the fact that regardless of how much the markets change, a few things will always remain the same. One is: making money in the markets is not easy. The good times can be much wilder, and yet, the bad times can be much more horrible. Invest in such a way that you can survive both. Avoid the risk of ruin. Just stay in the game.

I wanna leave you with something Robert Frey said in the video I linked above:

You can see here that […] this sort of low volatility period here, obviously, was followed by much more erratic conditions here. But preceding it were much higher levels of sustained volatility, plus these sort of volatility jumps here. And then there was another period of low volatility, and again, there was this peak here.

So, […] on the one hand, people are calibrating GARCH models and doing all kinds of crazy things. It’s ridiculous. I mean, they’re saying that we’re back to a new normal and everything’s not going to change again, where even a moderate historical perspective would have shown that this was a ridiculous idea. We don’t do it. We tend to look at these very short time periods, we tend not to be adequate historians, we get too hung up with the mathematics, and we should be better historians.

And you know, there’s sort of the last commentary: you don’t design a house based on the weather report. And that’s what many people do with their portfolios. They look at tomorrow’s weather forecast and build the house based on what they’re going to see.

Beautiful Article Bhuvan. It was really thought provoking and hopefully a wake up call to every investor.

Hi Bhuvan

Very well researched and well written article.

Thought provoking. I think I am going to have a really hard look at my investment philosophy. May be I am going to really think about the cockroach portfolio.

Thanks for the wonderful read

Bhuvan Hi,

Your article was so long that I preferred to listen to it aloud.

I will share something you may not agree with.

As a young man I would listen to BBC reporting on Black Monday for as long as it remained in the headlines.

I was dabbling with stocks when the dotcom frenzy was gathering momentum. I lived through the crash & the lull thereafter.

I clearly remember the the one way up months of 2007 & next 2008-2009 …

The rest is too recent.

Unless you are invested in the market with stakes significant enough to knock you cold should anything go really wrong, YOU WILL NEVER KNOW WHAT A BEAR MARKET IS NO MATTER HOW HARD YOU TRY.

Thanks so much for the thoughtful article. Very well written.

As per this markets crash data markets crashed once per every 4.5 years from the drawdown year , so its been already 4 years till now since 2020 crash let’s see will this data work or not in this year if its work iam one the person that enjoyed a lot I will put my all savings if not I will start Sip every month that’s my plan ,

Wonderful teaser/history of bear markets 👍

With the more transparent economic data and corresponding immediate regulatory measures, we may not have drawdown of previous kind.

I need more research about this topic

Option (derivative) is the best deal for overall stock market as per my little observation… Zerodha is making new India to mature India…

Hunter s Thompson also said ”buy the ticket, take the ride”