Why Does A Weak Rupee Upset Us?

The Indian Rupee is technically a free-floating currency. Practically, it is a managed free-floating currency.

What does this mean? And why does it matter to you and me?

As the exchange rate is inching closer to ₹86/USD, the INR is at its weakest. It is natural for the public to demand action from RBI, the central bank. A weaker currency is often seen as a connotation for a weaker economy.

But exporters rejoice when the currency weakens. Let’s say a manufacturer exported a chair last year for $5. So, he made INR 400 per chair – $5 multiplied by the exchange rate of 80/USD. The manufacturer still makes $5 on that chair, but in INR terms, it makes INR425 – $5 multiplied by 85/USD. Exporters make more when their domestic currency depreciates.

So, what is it about a weaker currency that upsets the public?

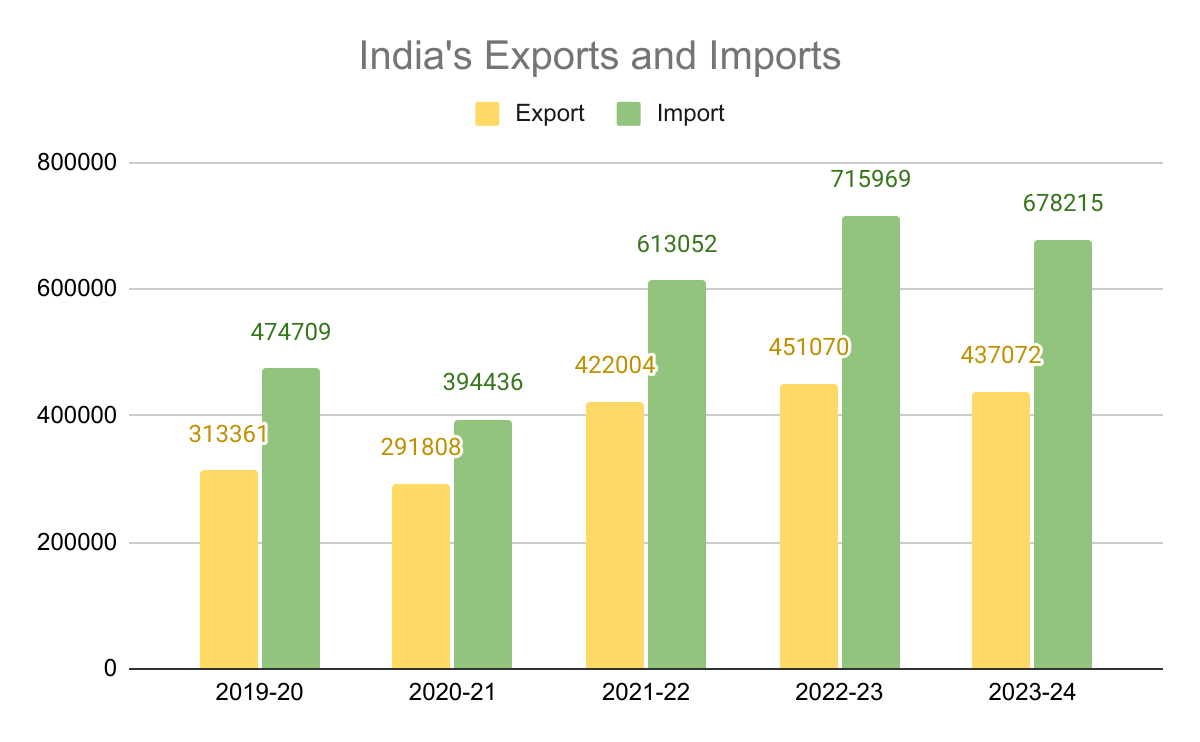

It is the imports. India still imports more than it exports. And as the INR depreciates, imports become more expensive. Let’s say you bought a perfume for $10 last year. You would have paid INR 800 – $10 multiplied by the exchange rate of 80/USD. You bought the same perfume today for $10 but paid INR850 – $10 multiplied by 85/USD.

Export and import aside, the government itself would not want a weaker rupee. Think about it, India’s external debt or loans taken from foreign entities stood at $664 billion at the end of March 2024. At the time, the exchange rate was hovering around 83/USD. It is now floating around 85/USD. Just because of currency depreciation, India’s external debt increased by INR1,32,800 crores.

What’s the calculation? Each dollar became expensive by INR2 as it moved from 83 to 85. So, the $664 billion debt also became expensive by the order of INR2/USD. So 664 billion multiplied by 2 equals 1,32,800 Crores.

Clearly, the government would want the RBI to control the exchange rate and not let the INR weaken. So, why does the RBI let the INR float freely against foreign currencies? Let me attempt a simplistic explanation.

- The exchange rate of a free-floating currency is determined by market forces. When the demand for a currency is higher, its exchange rate rises. When the supply increases, the exchange rate falls.

- Since the central bank is not involved in deciding the exchange rate, foreign investors feel encouraged to invest in the country. They know that the return on their investments would not be impacted by the exchange rate controls.

- If the exchange rate is not free-floating, foreign businesses will sell their products at a very high price to compensate for the whims of the central bank regarding exchange rates. That means imported goods could be expensive. If the imports are industrial goods or inputs, they could translate into widespread inflation across other products.

- A managed/controlled/pegged/fixed currency often leads to the creation of a black market. Since free convertibility of the currency is not available, people are often forced to pay a premium and buy foreign currency in black markets.

Basically, a fully free-floating or convertible currency is great. But for a developing country like India, full convertibility can also be challenging. Knowing that depreciation in their currency can be beneficial, Indians might start holding more dollars. And that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. The more dollars they hoard, the more it appreciates, and the rupee depreciates. But this will happen without a commensurate benefit in trade.

To reach a middle ground, the RBI occasionally intervenes in the currency market to keep random, extreme movements in check. It does not want to choose a direction for the exchange rate; it just wants to reduce its volatility, thereby avoiding any panic reactions from those with forex exposures.

Basically, the INR is a managed free-floating currency.

And how does the RBI manage the INR?

- Market Operations

If the INR falls too much, it is usually because of lower demand for INR or higher demand for USD. So, the RBI starts selling Dollars in the market. That way, INR in circulation will be reduced, and USD will increase. An increased dollar supply stops or slows down rupee depreciation.

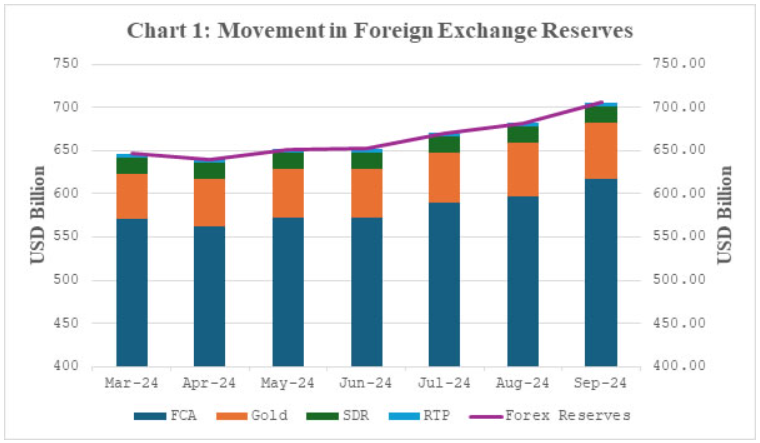

If the INR were to rise too fast, it could be because of a higher INR demand or a lower USD demand. So, the RBI would start buying and hoarding more USD to reduce the dollar supply in the market. A decreased dollar supply is expected to stop or slow down rupee depreciation. - Forex Reserves

RBI maintains USD and other currency reserves to use whenever it has to start market operations. These huge forex reserves helped RBI contain the exchange rate when post-COVID inflation ran up.

Reserves also act as a buffer for payments to foreign lenders.

- Interest rate adjustments

- Rate hike

Foreign investors seeking higher yields bring in more dollars, thereby improving the dollar supply and appreciating INR.

But investors, including foreign investors might trim equity exposure in the event of a rate hike. - Rate cut

Rate cuts could drive foreign investors out of India to other countries with higher yields.

But rate cuts are seen positively in the equity markets. So investors, including foreign investors, could put more funds into equities.

- Rate hike

- Capital Controls

- Remittance limits—Indians can send no more than $250,000 abroad annually. This control is meant to limit the demand for forex and keep extreme swings in check.

- Industry-level limit – The mutual fund industry cannot collectively have a foreign exposure of over $7 billion.

- Capital controls can be permanent, like the ones mentioned above. They could also be temporary that maybe imposed a reaction to some sudden swings.

Various domestic and international factors continuously impact the exchange rate of the rupee with all other currencies.

For example, the US Fed’s interest rate hike was seen as a major trigger for the USD to hit INR85. Global investors seemingly wanted to put more dollars in the relatively safer US economy as it increased yields on debt investments. The full impact of this has yet to be seen. The RBI has been delaying rate hikes in India, but the likelihood of a rate hike in February 2025 has increased, with inflation largely within the expected range.

Sometimes, the effect is both ways. The exchange rate affects the factors affecting it. For example, high oil prices would push the import bill up. This would increase the demand for dollars, thereby depreciating the rupee. A depreciated rupee is, in fact, expected to discourage imports.

Exchange rates are influenced by a web of multiple moving factors. The RBI does not try to insulate the economy from those fluctuations; it only tries to blunt their impact.

click

The recent depreciation in Rupee is also because of FED future forecast of less rate cuts in 2025 and FII selling to buy China and other other emerging markets.

Perhaps a correction is required – ”A decreased dollar supply is expected to stop or slow down rupee depreciation”. It should be appreciation not depreciation.