What did we learn?

It’s the end of another year. And that means it’s time to look back on the year and reflect on the mistakes that I made, and saw others make.

Why? I’m not sure. It’s the height of arrogance to think we learn from our mistakes. I don’t know about you, but I’m not one of those disgusting, smug people that actually learn anything. No, I like to wallow in my mistakes. The whole point of this post for me is to reflect on mistakes, find lessons to learn, ignore those lessons, and make new mistakes in 2025 — in style. I’ve been doing this for a few years, and it’s become something of a small tradition.

So with that, shall we get to it?

Who knows why anything happens?

In all my recent posts, I’ve talked about just how crazy the markets have been since COVID.

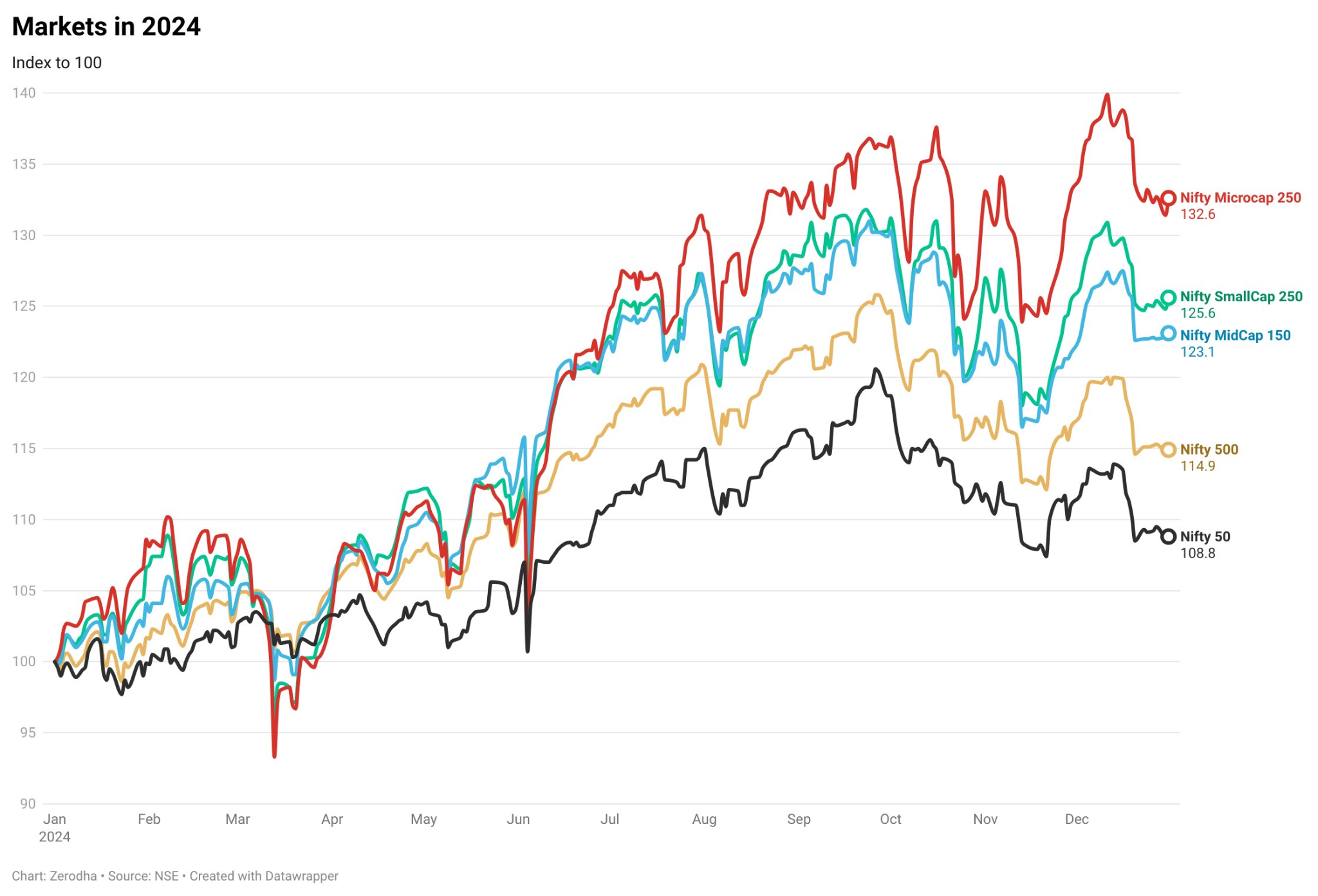

Since 2020, when the pandemic hit, the markets’ worst year was 2022. And even that wasn’t a negative year — it was simply flat. The largecap, midcap, and smallcap indices generated 4%, 3%, and (-)4% respectively. Considering the bloodbath the US markets were seeing, this was barely a scratch.

Then, 2023 was the opposite of 2022. It was spectacular. The largecap, midcap, smallcap indices, and gold all shot up — by 20%, 43%, 48%, and 14% respectively. Though I didn’t say this out loud in my post last year (because I am too chicken to publicly make predictions), I thought this meant 2024’s returns would be moderate, at best.

My non-prediction was spectacularly wrong. The Nifty 500 is up 16%. The Nifty Midcap 150 index is up 23%. The Nifty Smallcap 250 index is up 26%. Gold is up 20%. That’s a brilliant year, unless you think 40%+ returns every year are your god-given right.

It goes to show, once again: what you expect from the markets and what actually happens will almost always be the opposite — both on the upside and the downside. We should all stop pretending like we understand the markets.

Looking back at any year, it’s easy to feel like you know exactly why the markets did what they did. But if the market was really that predictable, we’d all predict it, and you’d make no money at all.

Everybody was a genius… again

For the second year in a row, it was hard to lose money. In fact, you couldn’t have lost money even if you tried.

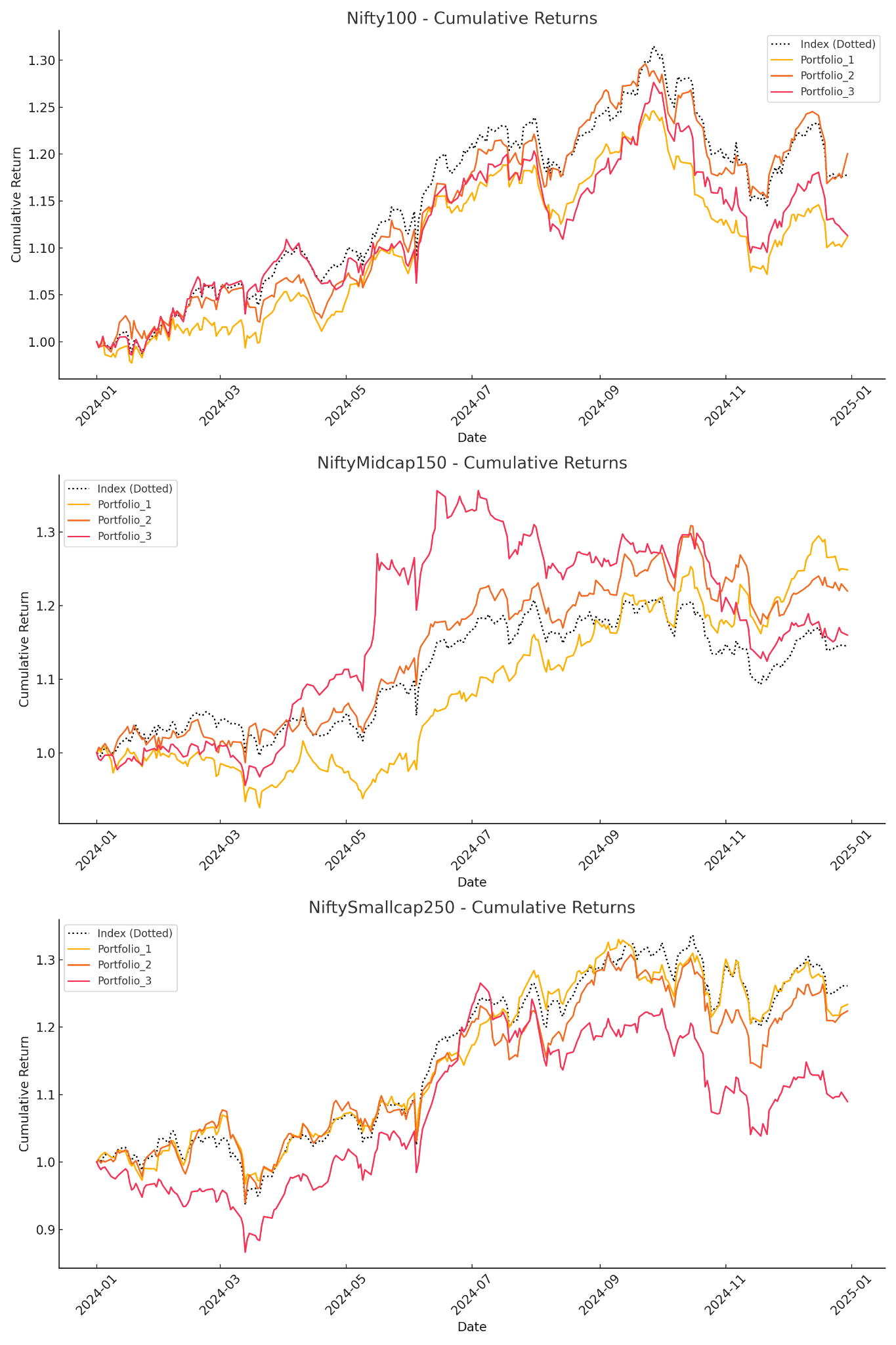

And we did. We ran a test, picking 3 completely random portfolios of 30 stocks each from Nifty 100, Nifty Midcap 150, and Nifty Smallcap 250 index.

Here’s what we saw:

- One of our Nifty 100 portfolios out-performed the index, while the other 2 under-performed. But the thing is, for much of the year, all these portfolios were broadly in line with the index. In absolute terms, no matter what portfolio you picked, you’d have still done better than a fixed deposit.

- All our Nifty Midcap 100 portfolios outperformed the index. Considering that the index was up 23% for the year, this wasn’t surprising.

- Our smallcap portfolios were slightly more surprising. While the index was up 25%, two portfolios stayed more-or-less in line with the index. Only one underperformed slightly.

But broadly, no matter what you did, you couldn’t lose money in 2024.

Honestly, if you somehow lost money in 2024, I don’t know what to tell you. Maybe visit the nearest astrologer. And temple. And, for good measure, sacrifice a few goats to a deity of your choice. And going ahead, only place buy orders after tying nimbu and mirchi to your laptop or phone.

Boring worked!

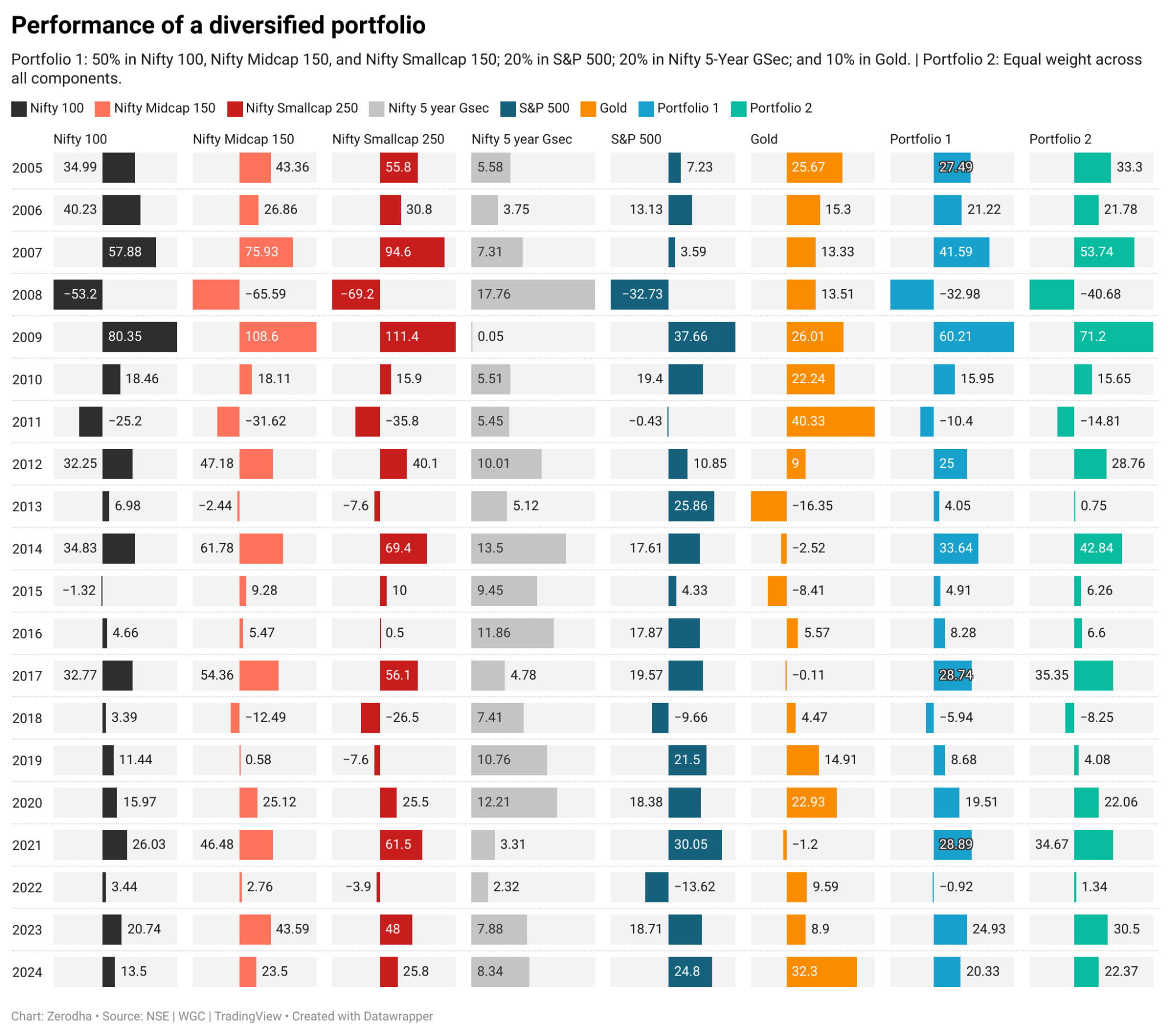

Diversified portfolios did well in 2024. Again!

It’s simple. I mean, you don’t even have to overthink it! Even basic asset allocation across asset classes would work. If you just equal-weighted equities, debt, and gold in your portfolio, you would come out of 2024 looking like a genius.

A lot of retail investors waste time looking for the “best stocks” and “best funds.” In reality, a dumb portfolio with a sensible asset allocation does reasonably well regardless of the market conditions. Unfortunately, that just sounds boring.

The problem with investing is that it seems too easy — until you lose money, that is. And eventually, everyone loses money. Until you lose money, boring things like index funds and diversification will always feel like the tools and strategies of low-IQ idiots. It’s only when the markets punch you in the face that your arrogance leaves your system, and you realise the benefits of doing basic things really well.

Investing is a brutal but incredible teacher. Investing lessons aren’t just about stocks and funds and making money; they also help you get through life — if you let them. In investing, as in life, the path to getting ahead is to do the obvious things well when everyone is losing their minds.

Predictions are a fools game

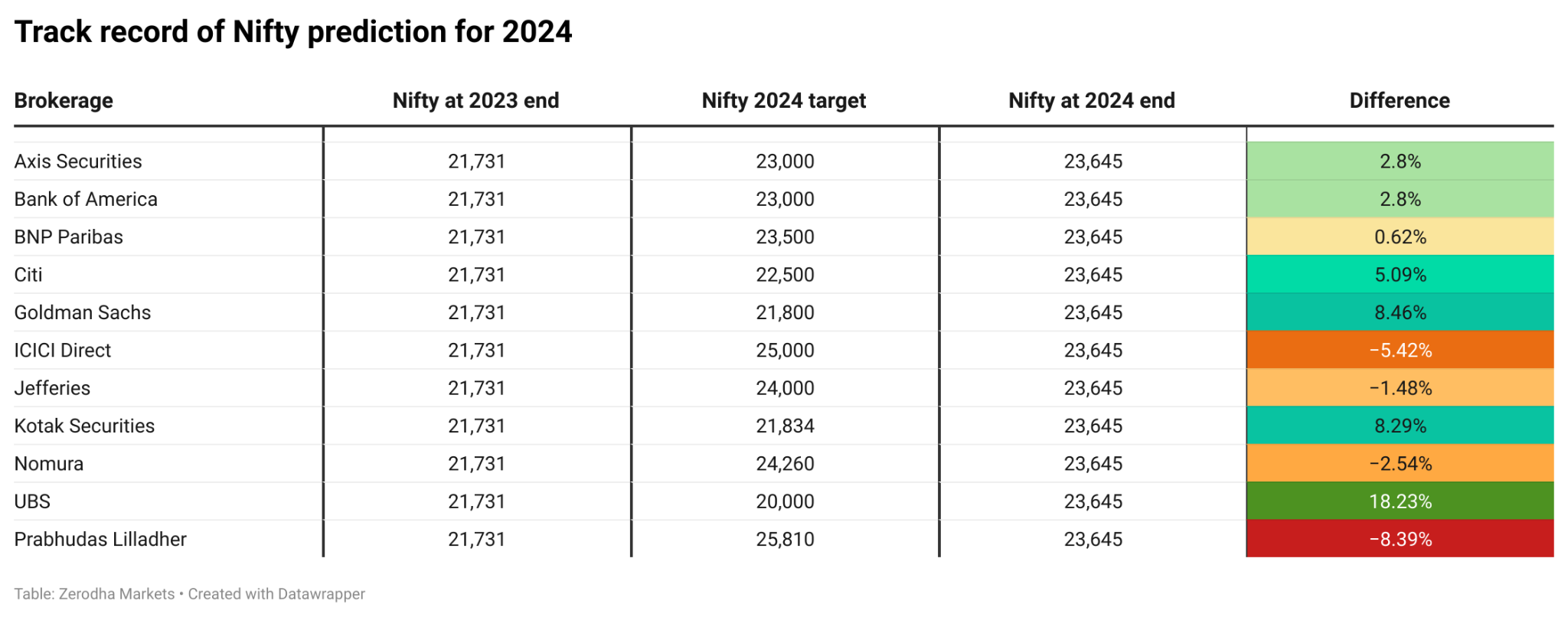

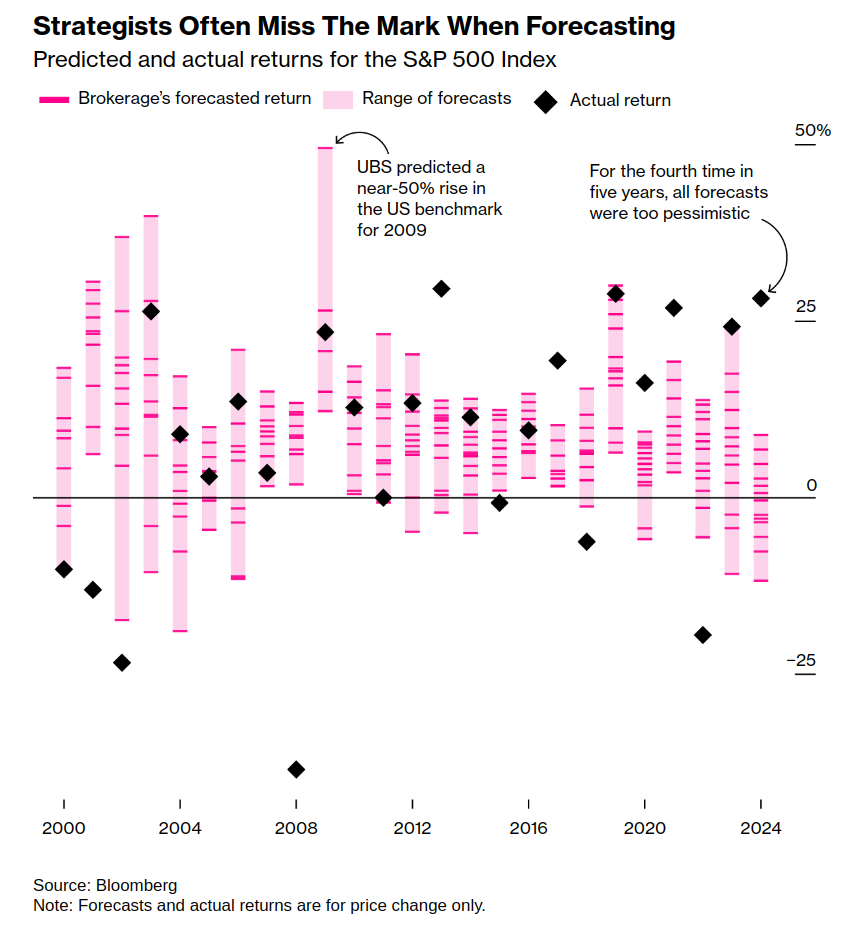

Last year, my colleague Meher did the grunt work of collating the Nifty targets of various brokerages and banks. The bottom line? A monkey throwing darts would’ve been more accurate.

We updated the analysis for 2024. Guess what? People still suck at predicting things. Who knew?

This suckiness isn’t just an Indian feature. Investment “experts” and “strategists” uniformly suck across the world.

Here’s another granular analysis of the suckiness of annual capital markets forecasts for different asset classes:

If people were so wrong for so long in any other industry, they’d be kicked out of their jobs and sued out of existence. But the stock market is a weird, upside-down place. It’s kind of stunning that strategists can make wrong forecasts year after year and still earn millions of dollars. Imagine a doctor or a lawyer being this wrong, this often! They probably wouldn’t even be allowed to graduate!

But hey, I guess that’s the world we live in.

Bear market? You ain’t seen anything yet!

One of the funniest things this year was the hysteria over the “bear market” towards the end of the year. All this mass cacophony was all over a ~5% fall from the peak. This is what happens when people are too used to easy returns. They lose their minds over insignificant fluctuations.

I feel stupid typing this next bit, but I will, nonetheless.

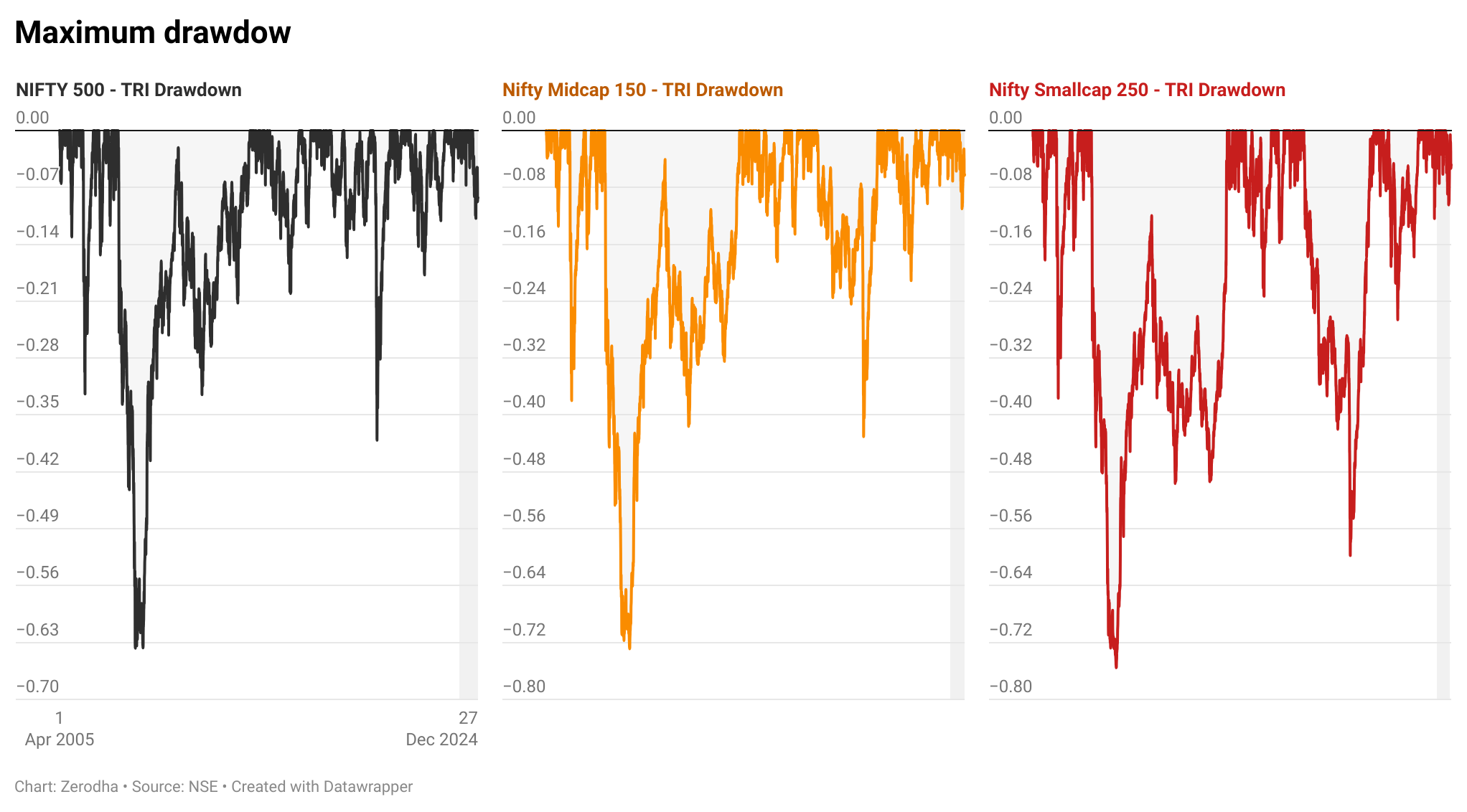

This chart shows the maximum drawdown or the maximum fall from a previous peak of each asset class. Look at the shaded area towards the extreme right corner of each plot. See that last, tiny little line? The one you can barely see because of all the other lines around it? That’s the “bear market”.

The current drawdown isn’t even a cut, let alone a bruise. That’s where we are. That’s what people are freaking out over. Funny, isn’t it?

This drawdown visualization is one of my favorite charts. It’s one of the best indicators of bad things can get. When the markets are actually down, they’re downright horrible. If you’re one of those people who thinks the markets are bad right now, well, you ain’t seen nothing yet. Things can be much, much worse.

Most investors in Zerodha are young. If you’re reading this, you’re probably young as well. That means, at the very least, you have 20-30 years left for your retirement, unless you’ve bought into the whole FIRE bullshit. At some point in your life, you’re practically guaranteed to see a really bad 2008 style crash. The only problem is: nobody knows when. When that does happen, things will be terrible. You might even feel like your whole life has been ruined.

But there’s a silver lining: those moments will teach you a lot about your temperament. And they’ll probably make you a better investor. I wrote about this earlier this year.

Markets are cyclical, stupidity is eternal

Every year, there’s one thing that surprises me over and over again, despite being obvious. And that’s the human ability to do phenomenally dumb things despite knowing they’re dumb.

Modern financial markets are over 400 years old. Everything about the markets has changed over the centuries. Except human behavior. In fact, some argue that the human brain hasn’t changed much over the 200,000-odd-year history of homo sapiens. We’re basically using stone age brains to deal with 21st-century realities.

And it shows. 2024 came with numerous examples of remarkable stupidity.

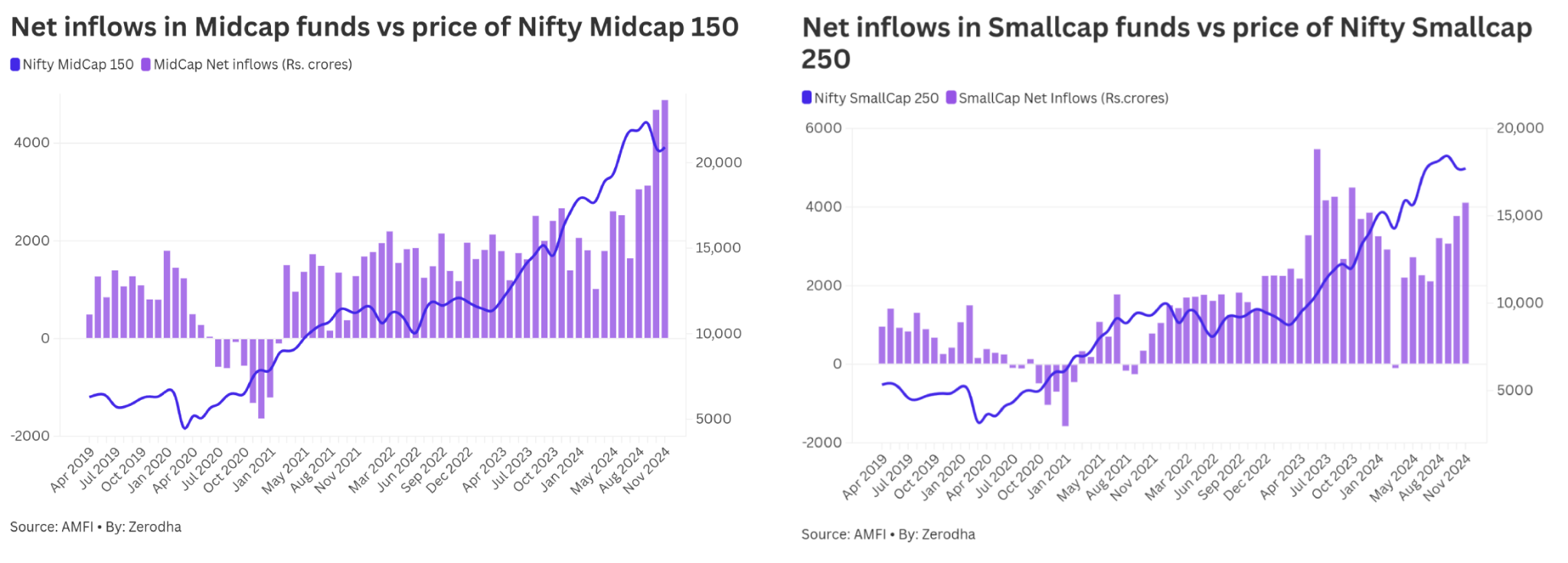

Let’s start with mutual fund flows. When something goes up, retail money inevitably follows it. This was the case with midcap and smallcap mutual funds in 2024.

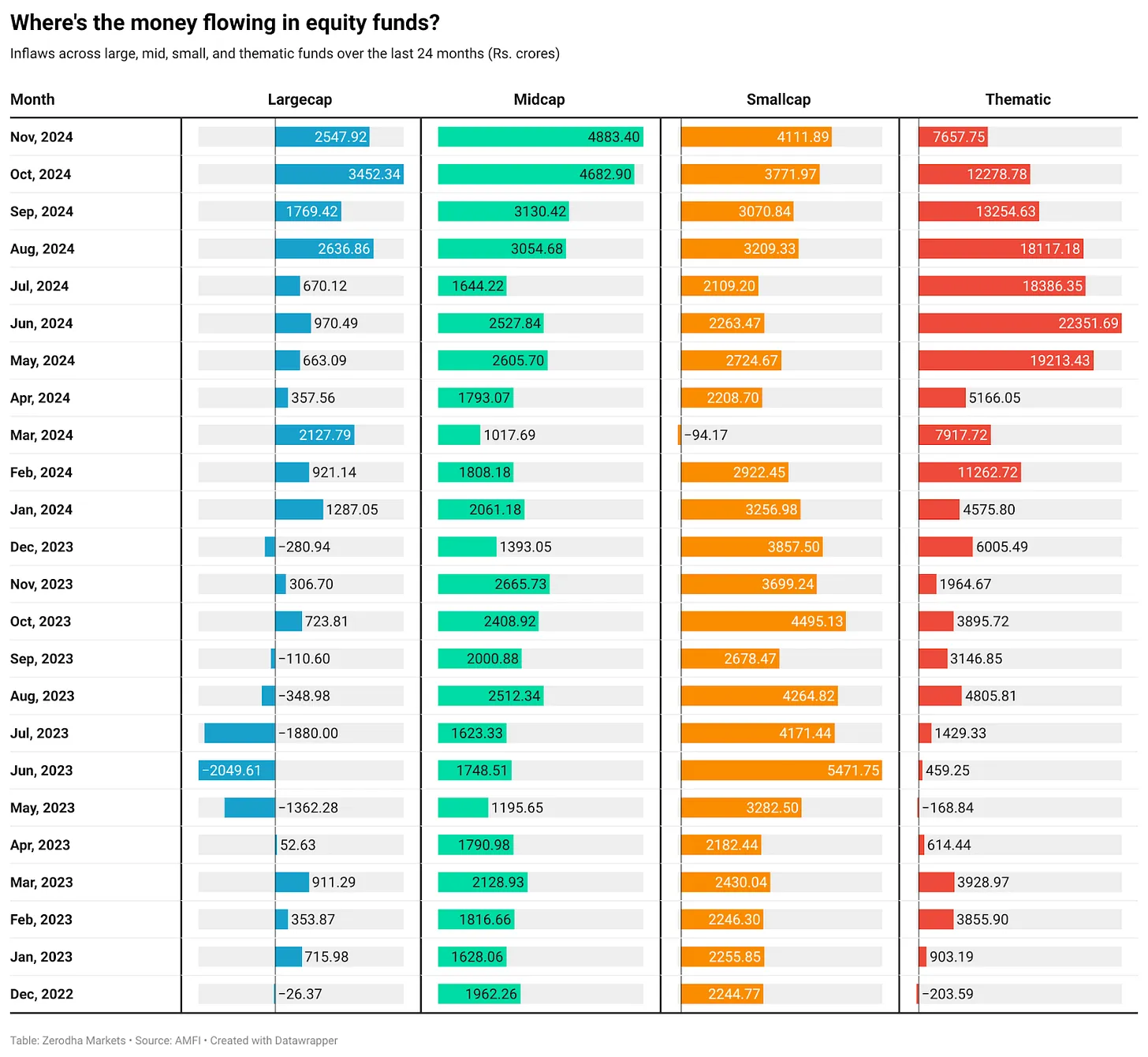

But that’s nothing. Perhaps the most absurd example of this performance-chasing was the crazy inflows into new mutual funds or NFOs. Specifically, the amount of money that flowed into new thematic funds like defense, consumption, commodities, etc. is just nuts.

Thematic funds are cyclical. They tend to go up more than the broader indices, but fall by just as much. They’re like small and microcap funds, but even more volatile. Whenever an AMC launches a thematic fund, it’s a good sign of a top in that particular theme. Take Defence for example:

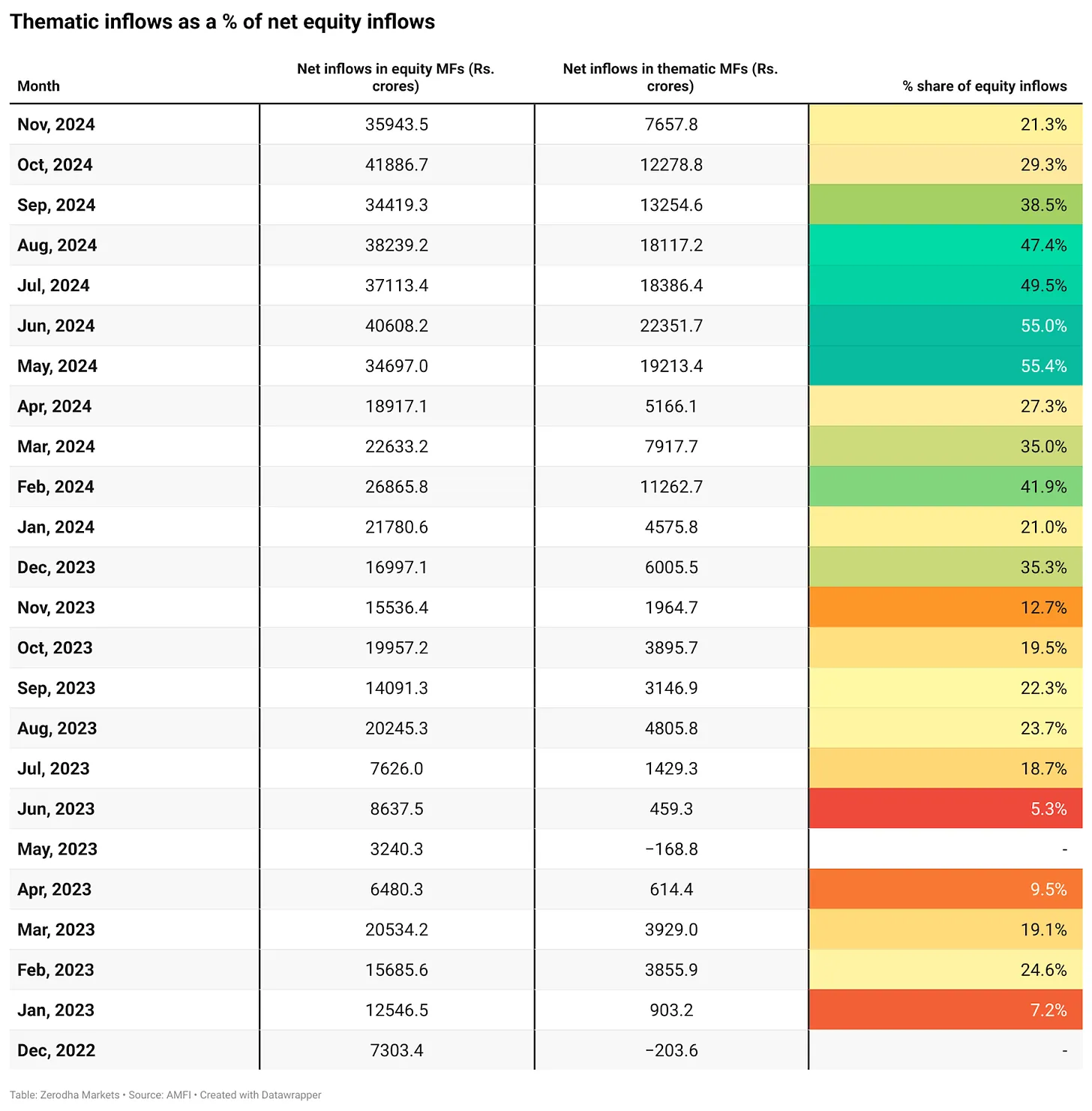

The numbers are mind-boggling. In 2023, that total inflows into thematic funds was Rs. 30,840 crores. In 2024, it was more than four times as much — Rs 1,40,132 crores. That’s insane! In fact, in 2024, thematic funds had more inflows than large, mid and smallcap funds all put together!

It becomes even crazier when you look at flows into thematic funds as a percentage of total equity inflows. This ranged between 30-55% throughout 2024. So people were investing more money into the shiny themes and sectors of the moment than broad diversified funds like large and midcaps.

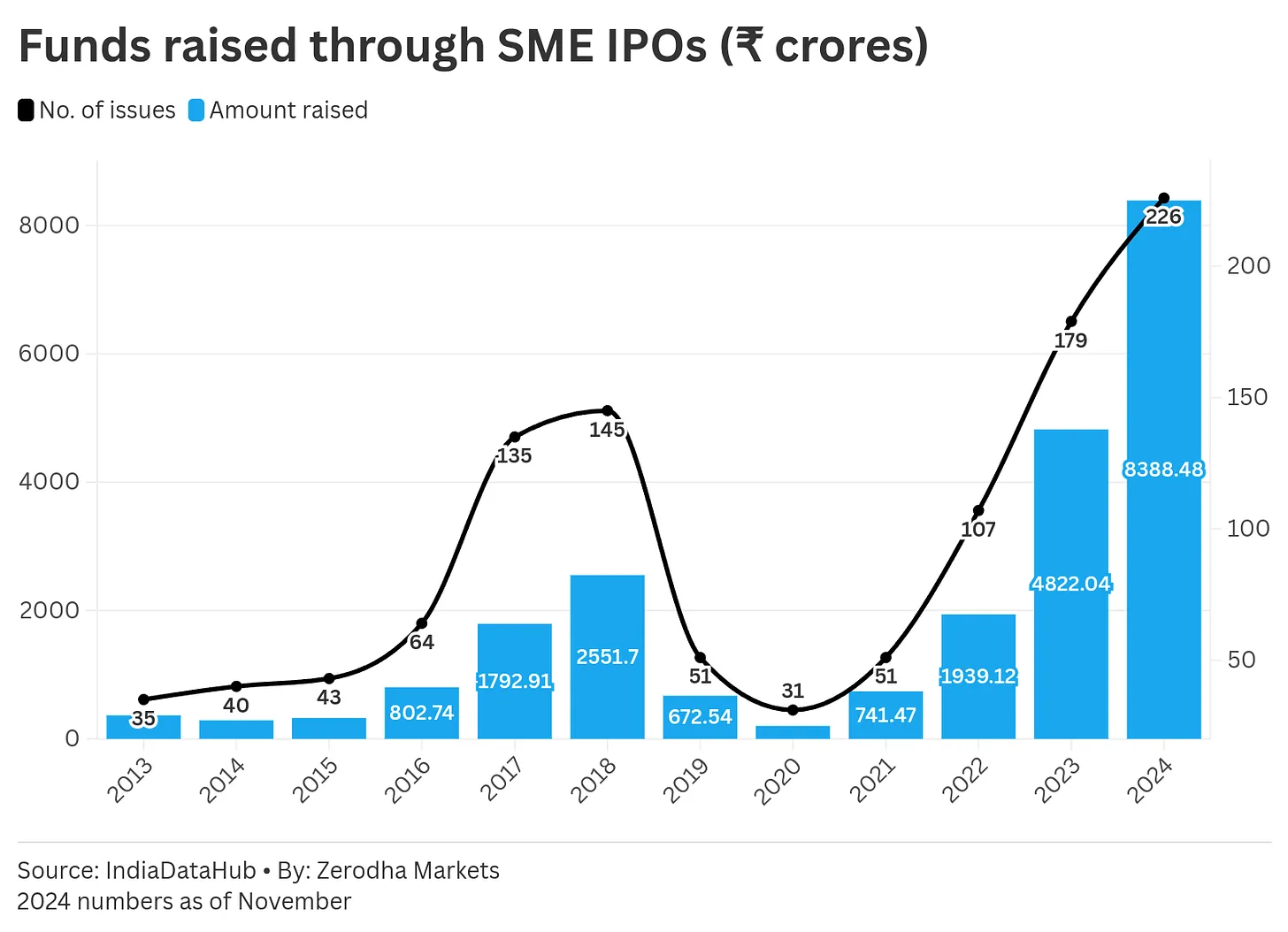

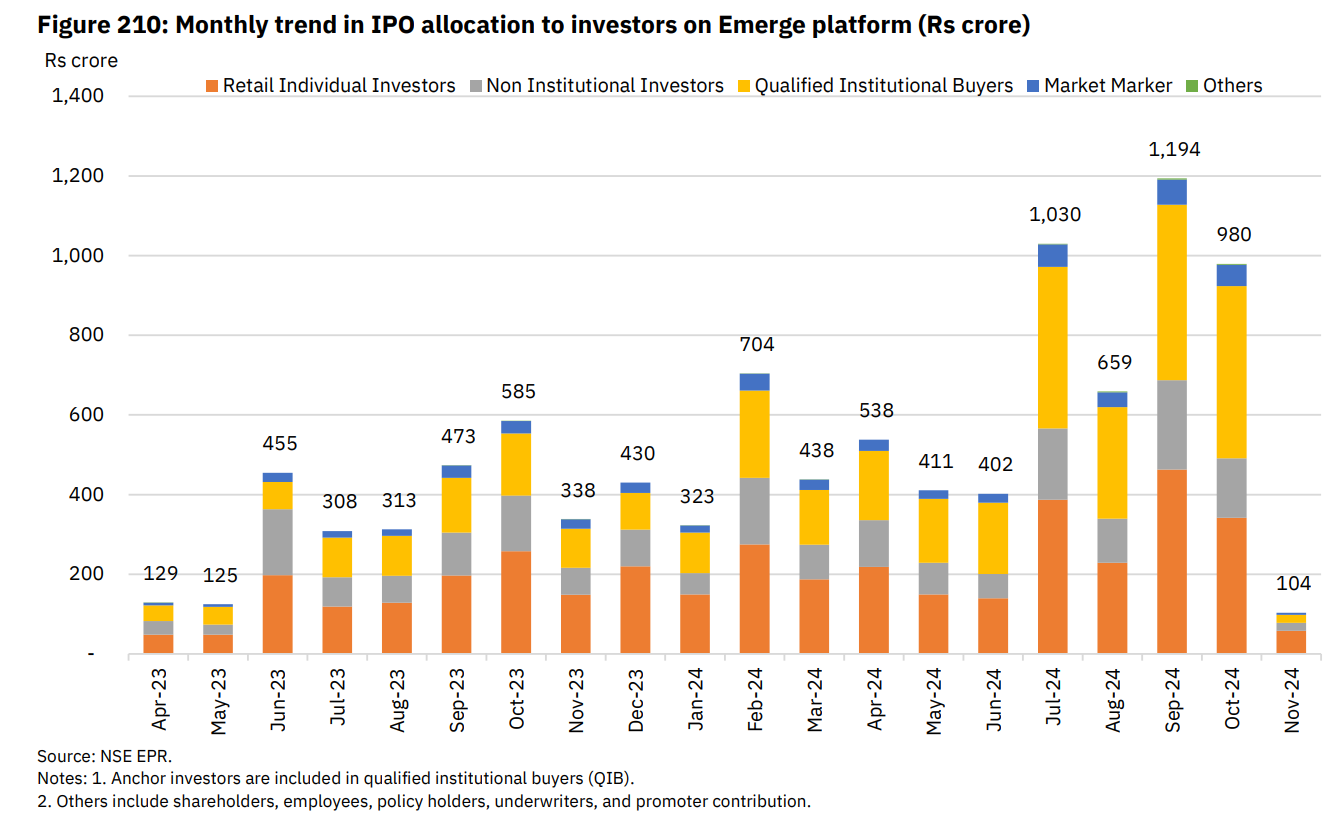

The craziness was also on full display in the initial public offerings (IPOs) of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs).

Even though the SME IPO platform has been around for a decade, for most of this time, it saw little activity. But thanks to the bullish market sentiment since COVID, there has been an explosion in the number of small companies raising money through IPOs.

In general terms, that’s a good thing. Small businesses have a tough time accessing capital. That’s the problem that the SME IPO platforms were designed to solve. It relaxed listing requirements and disclosures so that small companies found it easier to raise money.

But good things seldom come alone. They’re usually mixed with tons of nonsense. The SME platform is rife with examples of fraudulent companies raising money thanks to the lack of oversight.

Along with helping small businesses raise money, the SME IPO platform became an easy way for fraudulent actors to dupe retail investors by listing bogus companies. Investors that are blinded by the prospect of easy money from listing gains became easy marks.

I can keep going. 2024 was chock-full of stupidity.

One peculiar feature of post-COVID financial markets is the explosion of speculative activity in the markets. The madness was on glorious display in 2021 and 2022. It looked like it had died down towards the end of 2022, when interest rates rose, but it’s back! 2024 a rewind of 2021!

The markets have always attracted thrill-seekers, but there are very few historical parallels to the craziness we’re seeing after 2020.

It’s not just the level of speculation. There’s been a dramatic increase in the surface area of speculation. People have never had so many options to gamble. Junk stocks, shiny mutual funds / ETFs, options, crypto, NFTs, high yield credit, unlisted assets… the markets have more to offer to a gambling junkie than the best casinos.

To be fair, this is mostly a US thing. But it’s catching on in India as well.

Meanwhile, it’s also never been easier to gamble outside the stock market. Today, you can bet on anything from India’s GDP, to the weather, to Pushpa 2 movie collections, to fartcoin. There’s never been a better time to do crazy things with your money.

At the same time, the velocity of speculation has never been higher in the markets either. Everyone has a smartphone, everyone has high speed internet, and trading costs have fallen dramatically. Put all of this together and we seem to have turned into some sort of a gambling society. This might sound hypocritical coming from someone who works in a broking company. Go ahead. Judge me. But it’s happening in plain sight!

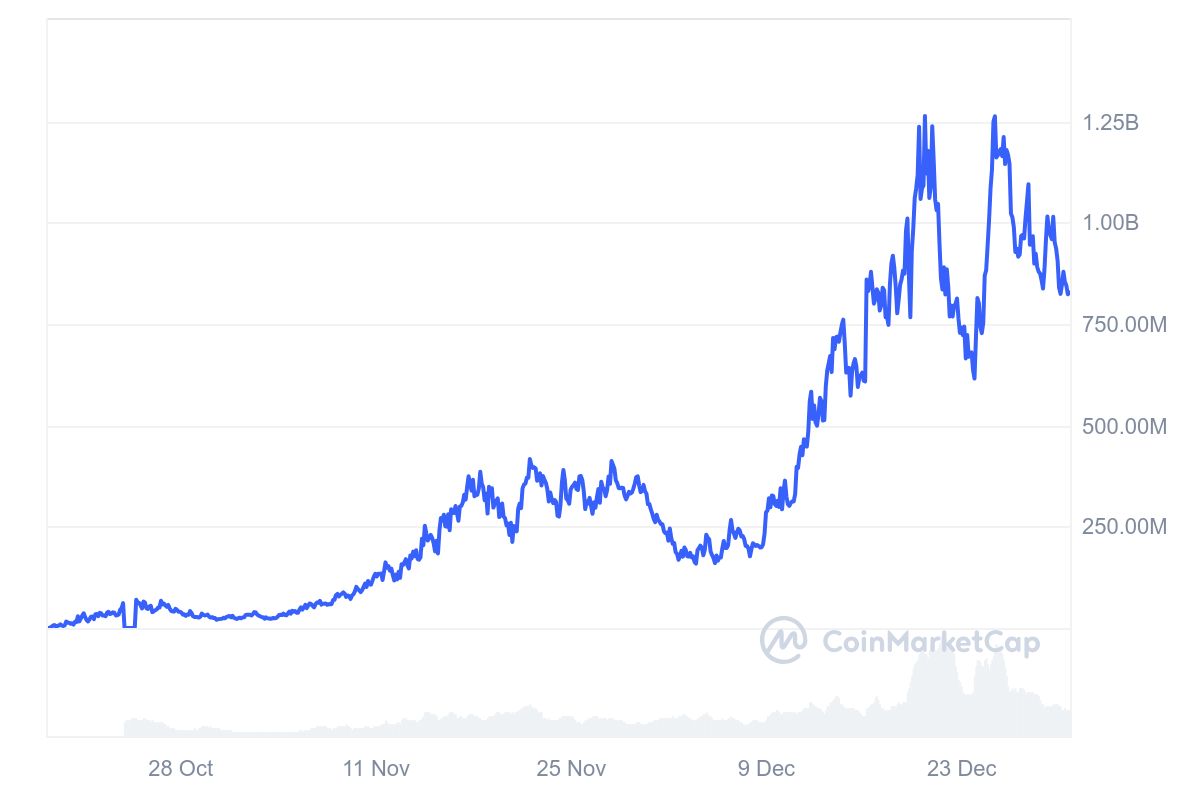

For a lot of people, speculation is becoming an end in itself. They could care less about the underlying value of what they’re speculating on. We saw this over the last few years — with the GameStop, AMC and Dogecoin sagas in the US, and junk stocks in India. But this year, the speculative spirits are getting even dumber!

This is the chart of Fartcoin. That’s a meme token created in October. At its peak, the token had a market cap of a billion dollars. The token has no utility, apart from featuring the word ‘fart’ in its name. Sadly, it was also not backed by the farts of the creators of the token.

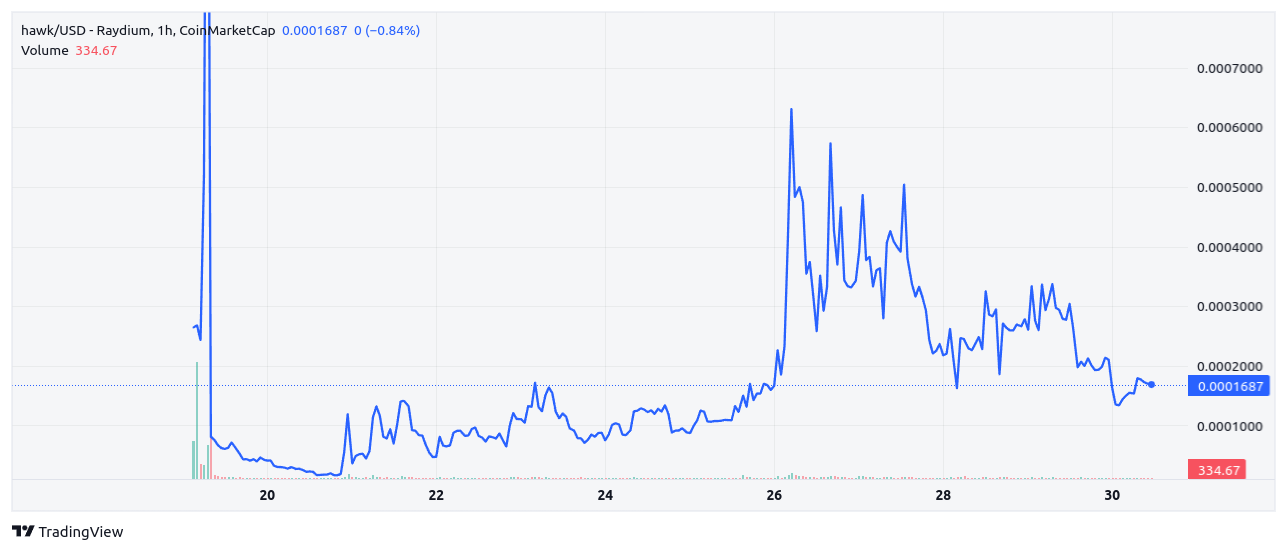

This is the chart of $HAWK, a meme token launched by the girl at the centre of the ‘hawk tuah’ meme. The token spiked at launch, and then crashed over 99% after the creators dumped the token. A classic pump-and-dump. I mean, you have to admire the moral shallowness of someone who could turn a ten second penis joke into a million-plus dollar fraud.

As Aristotle once said, “Do you want to cry about morals or make money, my fellow citizens!?”

But what’s causing this speculation?

Well, it’s always tempting to ascribe simple reasons for complicated phenomena. Having said that, a few reasons come to mind:

Gamifying ourselves to death

When you have an army of PhDs, NASA scientists and technologists all working with the singular objective of making people do something that’s not in their interest, this is what you get. Data scientist Jeff Hamerbacker put it best when he said “The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads.”

That sucks. But replace “ads” with the speculative activity of your choice, and it’ll still hold true. Speculating and gambling has never been more fun. Apps are designed to inject as much pure, unadulterated excitement-juice as they can, right at the bottom of your brain stem. You never stood a chance.

Peak capitalism and financialisation

There’s a certain kind of cliched belly-aching where you blame every little thing on capitalism. I am about to do exactly that.

The casino-fication of everything is probably the natural culmination of an ideology that thinks a good enough price system can solve all of society’s problems. When you take this belief system too far, its logical conclusion is the financialization of everything, and nothing is sacred anymore.

Is it something darker?

Is this rise of speculation and gambling a symptom of a deeper malaise at the heart of society — and by extension, the economy and markets? I have a speculative theory — but it’s not fully fleshed out. I have a separate post on this planned for later.

Narrative pollution

There’s a famous quote misattributed to mark Twain:

“A lie can travel half way around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes.”

When it comes to the markets, I’d paraphrase this as “A story can travel half way around the world while the truth is sitting with its pants down, taking a leisurely dump.”

In the 2022 edition of this series, I had written:

“It’s the same with the markets, they are inherently random and unpredictable, and we use stories to make sense of things. “The markets rose today because of the union budget” is much better than “I don’t know why the markets went up.” We tell a story by abstracting the actions of millions of traders and investors into a single headline. Stories are a coping mechanism.“

I still stand by this, but I’d like to add some nuance. I was listening to a podcast of Aswath Damodaran and he said something that stuck with me:

“We’ve forgotten that every evaluation tells a story. Whether you like it or not, when you put numbers on a company, you’re narrating its story. It’s your job to make that story explicit and ask yourself, ‘Do I buy it?’

We’ve lost the art of storytelling in valuation. It has become all about financial modeling. You’re an Excel ninja, you know all the shortcuts, but you’ve forgotten that every value has a story behind it.

This over-reliance on models and equations has driven out the narrative. People think they can just plug in numbers and get a valuation. But those tools are useless unless you can tell a compelling story about the company.

And when you tell that story, remember you’re not writing fiction. You can’t create fairy tales. We might want happy endings, but if you’re valuing a company like Bed Bath and Beyond, it’s going to be a horror story whether you like it or not. There’s no light at the end of the tunnel.

I call this ‘bounded storytelling.’ You tell stories that reflect the reality of where a company stands.”

I hadn’t thought about stories this way. Not all stories in markets are bad. Good stories are sound, big-picture abstractions of reasonable investment theses.

But not all stories you hear about the markets fit this description. Most stories are bad. More often than not, investors just look at surface-level narratives to rationalise their decisions, and then run with them.

With crypto, that story is the promise of disrupting and replacing the traditional financial system. With AI, it’s nothing short of total, humanity-wide revolution. With gold, it’s the promise of insurance against some horrible thing that’s about to befall the markets. Of course, history rarely works this neatly. But who cares?

Take defence funds — the darlings of investors this year. In sales presentations, they were hyped up with a nice little story: the world has become a dangerous place after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and countries — especially large ones like India — may have to manufacture hundreds of thousands of guns, bullets and bombs at home. The government will splurge lakhs of crores, and all this money will go to defence companies.

So… buy defence stonks and funds TODAY!!

More often than not, catchy stories are catchy precisely because they by-pass critical thinking and hit people right at the part of the brain that processes emotion. We humans are storytelling creatures. Stories are how we make sense of the world. We even reason in stories. Which means we aren’t wired to evaluate the stories we hear critically. Most stories, especially those in the markets, slip past our mental defences.

On top of that, there’s an entire bullshit-industrial complex dedicated to concocting delicious tales around whatever shiny fad is in demand. Brokers, research analysts, consultants, talking heads on TV, snake-oil salesmen on social media… there’s a whole ecosystem of people whose livelihood depends on peddling stories to you. And nothing is more dangerous to a portfolio than a well told story by someone with something to sell.

Investing is hard because you have to be on guard against this army of story-peddlers, whose success depends on slipping a quick one past you. In the digital era, being extra-skeptical about everything by default is a lifesaver — especially in the markets. There’s no way you can actually do a thorough fact-check of every little claim thrown your way. This is precisely why you should doubt everything you hear at least a little bit. Ask questions first, everything else can come later.

Woe unto the macro tourist

Among all the stupid mistakes investors make, the dumbest is “macro tourism”. Macro tourism is an investment style where you invest based on a surface understanding of big picture macro events. For example:

- Iran attacks Israel. This is bad! Israel will retaliate. Which will force Iran to speed up its nuclear plans. Which will lead to war in the Middle-East. Which will pull in the United States. Which will force Russia and China to support Iran. We’re about to have World War III! Sell all investments!

- The US Federal Reserve is recklessly printing money. Oh no! Trillions of dollars will be added to America’s already-huge debt burden of $30 trillion. Soon the US will have to default! If the US defaults, the entire global financial system will go down! That will cause the greatest depression we’ve ever seen! Sell stock, go all in on gold and/or crypto!

- China is in economic trouble. It will soon face a reckoning! Its economic model is bound to collapse! When that happens, the global economy will enter a recession. Go short on commodities! Sell stocks!

- The US yield curve is inverted. The Sahm rule has been triggered! Every inversion is followed by a recession, according to this Twitter thread I read! Sell stocks!

- India’s GDP is falling. Consumption indicators are all weak. The government was propping up the economy with its investments, but it’s run out of steam! If people don’t spend, sales of listed companies will fall! And stock prices will never go up! Sell stocks!

These are just a few of the naive macro narratives many retail investors confidently rely on to invest their hard-earned money.

These always get people into trouble.

One of the big problems with macro investing is the same thing I mentioned above — we think in stories. Stories create a false sense of confidence, and push us to stupid conclusions.

Another big problem is the illusion of knowledge. Follow macro news for long enough, and you start confusing the random snippets of general knowledge in your head for a coherent, complete understanding of the entire world. You soon feel like only you see the actual potential, or risks, in the market — the rest are just blind sheep walking off a cliff.

The third problem is an extension of the first and second. For 99% of humanity (and for all of history before that), we lived in the wilderness, with risks lurking around the corner. Until the last 100-odd years, the average life expectancy was around 30. With all those risks everywhere, our brains became exceptionally sensitive to fear. We evolved to pay more attention to negative news than positive news.

Thanks to this, we have an innate negativity bias. Doom stories automatically resonate more with us. Positive news barely makes headlines, while even small bits of negative news go viral. This is even stronger with macro. Doom-porn macro headlines usually make all the noise, while positive macro news items are barely discussed.

I listen to macro podcasts and read big picture macro articles. Each time, I come off terrified that the end of the world is imminent, and our financial systems will collapse. That rarely pans out. Doom-porn pulls all the negative things that can possibly happen in the future, and makes them seem like the realities of the present. The negativity occupies so much of our psyches that we can’t think straight even if we want to (not that we do).

The macro guys may well be right. China might implode. WWIII could erupt. The dollar could collapse. The Fed could go bankrupt. We might hit a point where the stone age is the best case outcome. But understanding macro events and making money are two different things. For every successful macro investor, there are thousands that have underperformed a saving bank account — let alone a fixed deposit.

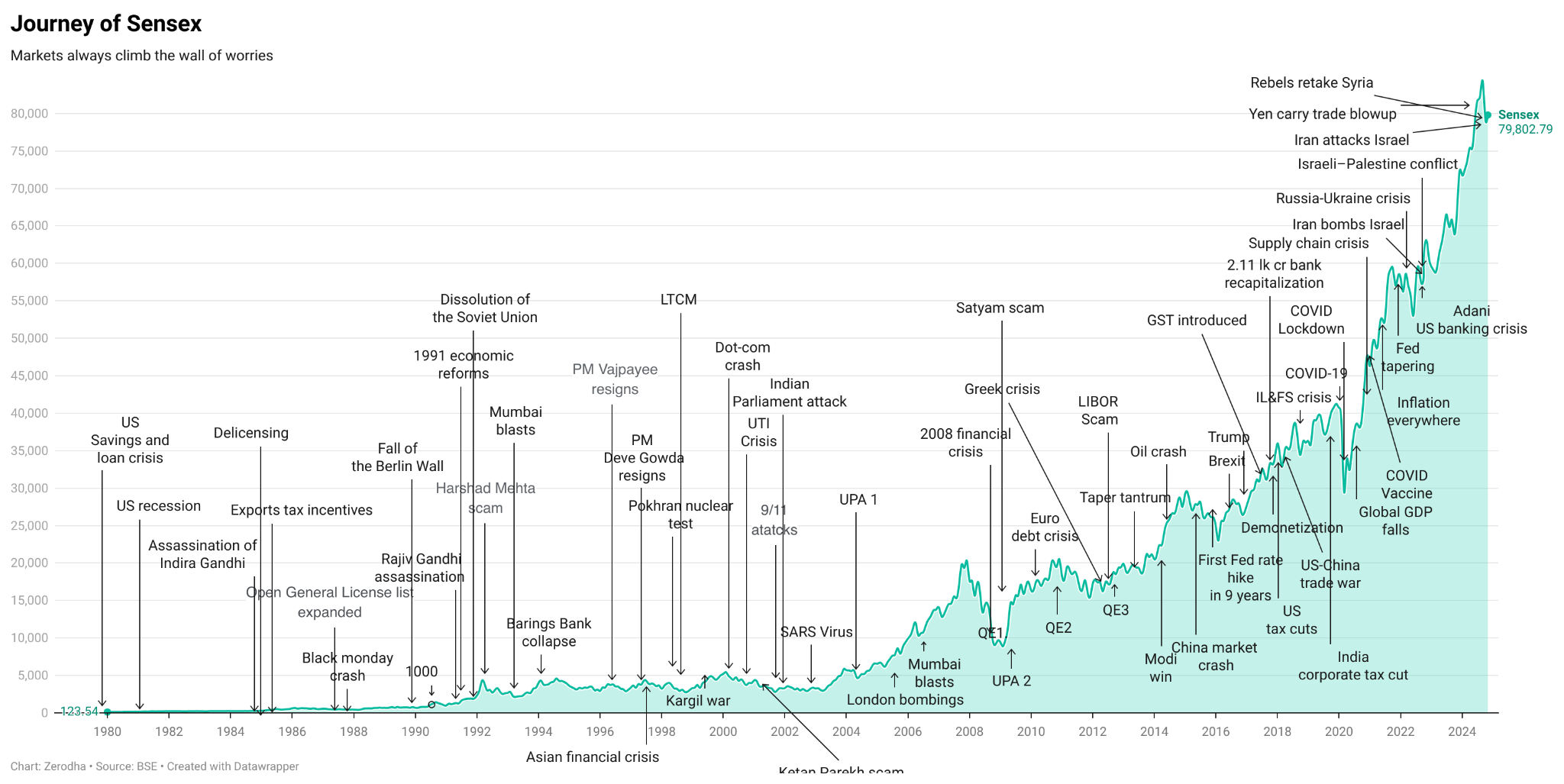

People have been screaming about the end of the world for centuries. Yet, here we are. This is one of my favorite charts and I include this in every year’s post, because it drives home a simple fact: pessimists sound smart; optimists make money.

The stock market is a complex adaptive system. If you try understanding something this complex through simple, two-line stories and then make investment decisions with real money, you’re being reckless.

Build a toolkit

One of the best pieces of financial advice I came across in recent years was this little gem from Morgan Housel:

“Someone recently asked how my investment views have changed in the last decade. I said I’m less judgemental about how other people invest than I used to be.It’s so easy to lump everyone into a category called “investors” and view them as playing on the same field called “markets.”

But people play wildly different games.

If you view investing as a single game, then you think every deviation from that game’s rules, strategies, or skills is wrong. But most of the time you’re just a marathon runner yelling at a powerlifter. So much of what we consider investing debates and disagreements are actually just people playing different games unintentionally talking over each other.”

None of the world’s successful investors — from Warren Buffett, to Charlie Munger, to John Templeton, to Bill Miller, to Monish Pabrai, to Howard Marks — do the same things. They’re all playing different games. Their success comes from how they stick to the game they play, and how well they play it.

Here’s something else that Professor Damodaran said in this podcast:

“I love Peter Lynch. I love Warren Buffett. I also like what George Soros does. I think there’s something to be learned from every great investor and every investment philosophy.

If you ask me what the best philosophy is, my advice is to look inward. Figure out what makes you tick, because that’s going to tell you what the right philosophy for you is. It’s not about what worked for Warren Buffett; it’s about what’s going to work for you.”

Such a brilliant point! There are a hundred ways to make money in the markets. But you need to find the one that works for you.

How, you ask?

Understand yourself. Investors often look outwards for the “secrets” of other investors, spending entire investing lifetimes searching for money trees. They rarely bother doing a self-inventory of their own strengths and weaknesses.

Investing looks deceptively simple. In reality, though, it’s a bloodsport. It’s a fight against yourself. You need to avoid being dumb, even while you keep all the things that make you human — greed, fear, and hope — intact. That’s a Sisyphean task. Every time you look at your portfolio, that day’s market moves will arouse greed, fear, hope and a hundred other emotions in you. To sit quietly and ignore the screams of your monkey brain is easier said than done.

Then what can you do?

Here’s how I found my way around this question. Within the first few years of my investing journey, I realised that I have no edge whatsoever over the country’s smartest investors. There was no point in me trying to be a stock picker or a trader. I neither had the ability nor the temperament to be successful in either.

The best thing for me was to just buy some low-cost index funds, diversify and chill. But I had to learn this the hard way, after making many mistakes. Along the way, I realised that, as someone who is remarkably below average in many aspects of life and investing, bad decisions were inevitable. What I could do, though, was follow some simple rules, and avoid all the basic, common mistakes that I could anticipate.

I needed a toolbox with simple tools for my investing journey.

For more on this, you can check out this recent podcast featuring William Green, the author of Richer, Wiser, Happier: How the World’s Greatest Investors Win in Markets and Life. It’s a wonderful conversation with many takeaways.

Here’s one thing that stood out to me. The world’s great investors all have developed tools that work for them after looking inward. Green gives numerous examples:

- Charlie Munger spent an entire lifetime always looking for evidence and views that disagreed with and disproved his views. He also used the now widely popular tool of inversion — which is to flip a question or a problem on its head. For example, achieving brilliance is hard, but avoiding stupidity is easier. This is a big part of my own life and investing philosophy.

- Many investors find an intellectual sparring partner to keep their biases in check. Green points out how Buffett referred to Charlie as the ‘Abominable No Man’, because he said no to so many things. Similarly, Daniel Kahneman appointed Richard Thaler to point out when he was being stupid.

- Ken Schoenstein, a successful VC and a doctor, used evidence from addiction literature to come up with a framework called HALPS — which stands for “Hungry Angry Lonely Pain Stressed”. He figured that in these states he would always make mistakes. And so, he would slow down decision-making in those states.

- All the successful investors that Green interviewed also think probabilistically. Instead of falling in love with a specific idea, they stuck to bets where the probabilities were in their favour. They looked for opportunities with limited downside and high upside. In my own experience, this is how I think about good investing behaviour. By not doing dumb things, I can be more successful than 80% of investors. That’s a massive asymmetric upside in my view.

- William Green asked Ed Thorp “how do I know if I have an edge”. Thorp answers, “if you are asking that question, you don’t have one.”

- Great investors are information-processing machines. Not only are they learning a great deal, but they’re also constantly unlearning things and killing their darlings. Green gives the example of how Warren Buffett, at the insistence of Charlie Munger, changed his prized approach that he had learned from Ben Graham.

These are just some examples that come to mind from the conversation. All these anecdotes point to tools. These tools are what these investors use to be good at what they do.

I don’t mention this to say that we all should read books about successful investors and ape them. Not at all.

The point I am making is that we would do well to assemble a unique toolkit of our own — that specifically works for us. You need habits that specifically protect yourself from your own unique biases and weaknesses. Not just that, you need to be open to being proven wrong. Investment success is downstream of intellectual honesty and humility.

So. What did you learn?

I hope you were kidding about not learning from your mistakes and avoiding the learnings.

If not, that’s concerning, for you.

Besides that a good read

Remarkably engaging piece of writing.Realised again not to be driven by stories sold by marketing heads.

That was one football length of a post well dribbled to the goal…not a big cricket fan..hope is what keeps the market skyrocketing while fear is the downfall…looking forward for such intresting articles..

Good work. So much points covered.

Super awesome content brother

You have a very good skill of mixing homour and technical data to present a very interesting blog

Good piece written Bhuvan, I think people have not even seen one bit of what crash is. Imagine if a crash happens the money which is getting pumped like crazy in the market will all dry up. Also, these AMCs are very cunning at taking advantage of retail investor launching thematic funds only after that particular stocks have given a run-up. These butchers you know…. Phew!!🥲

Markets are cyclical, stupidity is eternal! 😀 the best line.

I used to wonder about why this was the case. I know eating burgers frequently isn’t so nice for my health. But still ended up eating one every alternative day – telling myself how bad can one burger be. Turns out I (we) tend to be too focused on single datapoints and discount it carelessely and lose sight of the forest.

I wanted to say Happy new year Bhuvan but after reading your post would rather say – Hope the people (incl. me) in the world become better by the end of 2025 than at the start of it.