Robo-advisors are dead, long live robo-advisors

The last couple of years have been brutal for startups. The exuberant venture capital investing cycle that began in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis is over. Venture capital investors have pulled back on investing across the board. Given that money once again has a cost, you can hear popping all around—the sound of all the bubbles bursting. In this more or less decade-long VC cycle, there were numerous ‘megatrends’ (pardon my VC speak). One of the biggest VC trends was fintech.

‘Fintech’ is a portmanteau of finance and technology. Fintechs are new-age companies that use technology to deliver superior financial experiences across banking, wealth management, payments, credit insurance, etc. Given that everybody uses technology in some form, though, fintech is a buzzword that kinda means nothing. In wealth management specifically, one of the hottest fintech trends over the last decade was robo-advisors.

Robo-advisors first became popular in the United States, the ground zero for all major fintech trends, and then quickly spread across the globe. The definition you may have heard is that “robo-advisors are platforms that offer automated financial advice“. There are two issues with the definition:

- Robo-advisors offered investment advice, not financial advice. One is a subset of the other. I explain this in detail later in the post.

- Many platforms that are called robo-advisors aren’t really that, because some also offer add-on human advice. If there’s a human in the back-end, what does that make the robo-advisor? A hybrid robo-advisor? Semi-robo-advisor?

Like fintech, this definition has also become increasingly meaningless.

The first robo-advisors came up around 2010. Despite the hype, most of them have either died or been acquired in fire sales. This was a stunning and violent end to what was arguably one of the biggest trends in wealth management. So what went wrong? Here’s an unofficial history of robo-advisors and why they failed. I also talk about robo-advisors in India.

A brief brief history of US advisory landscape

I can tell you about the rise and fall of robo-advisors as it happened, but the story would be incomplete without understanding the historical context of how robo-advisors emerged. Discussions without this historical context give you a fuzzy understanding of the financial advisory landscape at best. Also, I believe the broader trends in financial advisory in India are similar to those that have played out in the United States.

The first financial advisors in the US were stockbrokers who earned commissions on transactions. They weren’t advisors in the strictest sense of the word, because their incentives lay in generating a brokerage. But considering there weren’t a lot of registered investment advisors (RIAs), broker-dealers were advisors for most people. Independent RIAs started becoming popular much later – say post the 2000s. Life was good for stock brokers until 1975 because the US brokerage industry operated under a fixed brokerage mode—all brokers had to charge the same commission.

This was a legacy of two factors. The first was an agreement in the year 1792 between 24 brokers, who agreed to a minimum brokerage of 0.25% to avoid ruinous competition. These brokers would eventually form the The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). The second was the great depression and stock market crash of the 1930s. In response to the crash, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) was formed to regulate securities markets, and the SEC capped brokerage commissions to prevent excessive commissions.

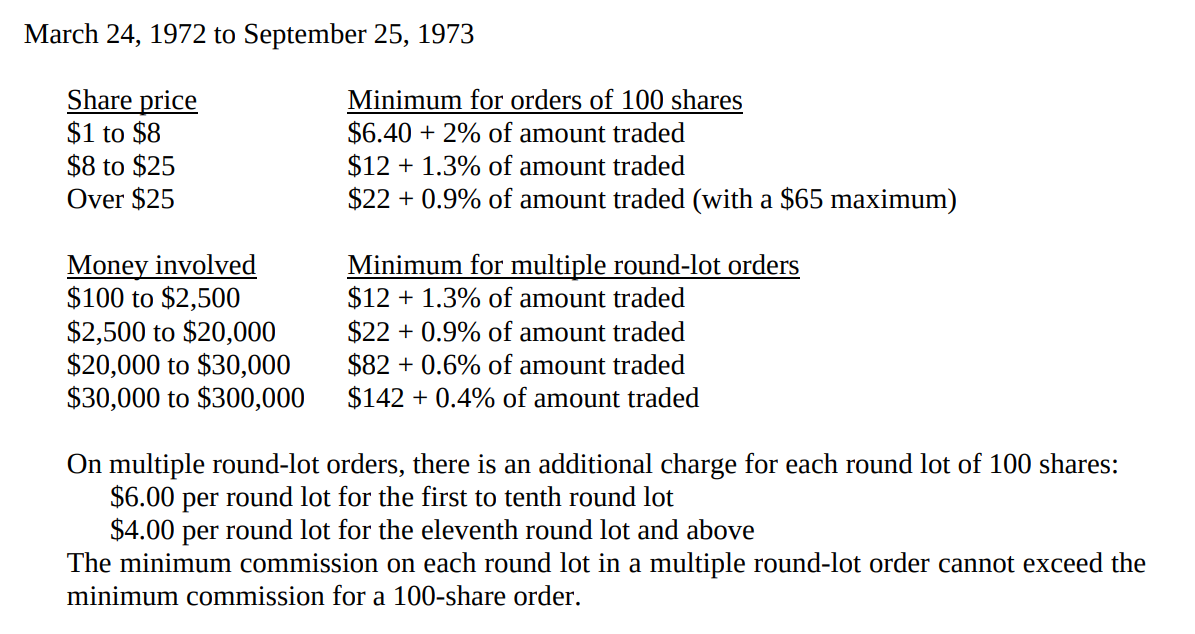

This fixed brokerage arrangement was good for the broking industry because you could charge the same fixed brokerage per share regardless of volumes. The effort brokers had to put into a transaction of 1,000 shares and one of 100 shares was the same, but the brokerage they earned could go up tenfold. Though the brokerage structure evolved and became more convoluted, brokers still made a killing. They charged high fixed commissions for both small retail investors and large investment pools like insurance companies and pensions, which were now controlling hundreds of billions in assets.

In 1975, the SEC deregulated fixed commissions and allowed them to float. According to one estimate, in 1975, broker revenues accounted for over 50% of Wall Street revenues. By 1984, they had fallen to 23%. New-age brokers like Charles Schwab and TD Ameritrade drove broking costs down dramatically by leveraging newer technologies. By the 1990s, costs had fallen by 90%. Their broking services became free in 2019.

Source: Jones (via SSRN)

As broking commissions fell, ‘advisors’ changed their pitch from “we’ll help you find the next hot stock” to “we’ll help you find the best stock picker” through mutual funds. They moved away from stock commissions to earning yearly commissions for as long as the investors remained invested in the mutual funds. This new commission-based advisory model, however, only lasted until the 1990s.

Starting in the 1990s, so-called “discount brokers” like Schwab and E*TRADE became popular. They started promoting commission-free investing in “no-load” mutual funds—the US equivalent of direct mutual fund plans. They also offered various investment tools to help investors screen and choose mutual funds. At the same time, DIY investors had other free tools like Morningstar and Yahoo! Finance, which helped them pick stocks and mutual funds on their own. These developments threatened mutual fund commission-based advisory models. Advisors evolved again. They moved from recommending mutual funds to offering asset allocation solutions for investors.

Along with this, there are a couple of other trends that are important for the eventual popularity of robo-advisors.

The popularity of index funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs)

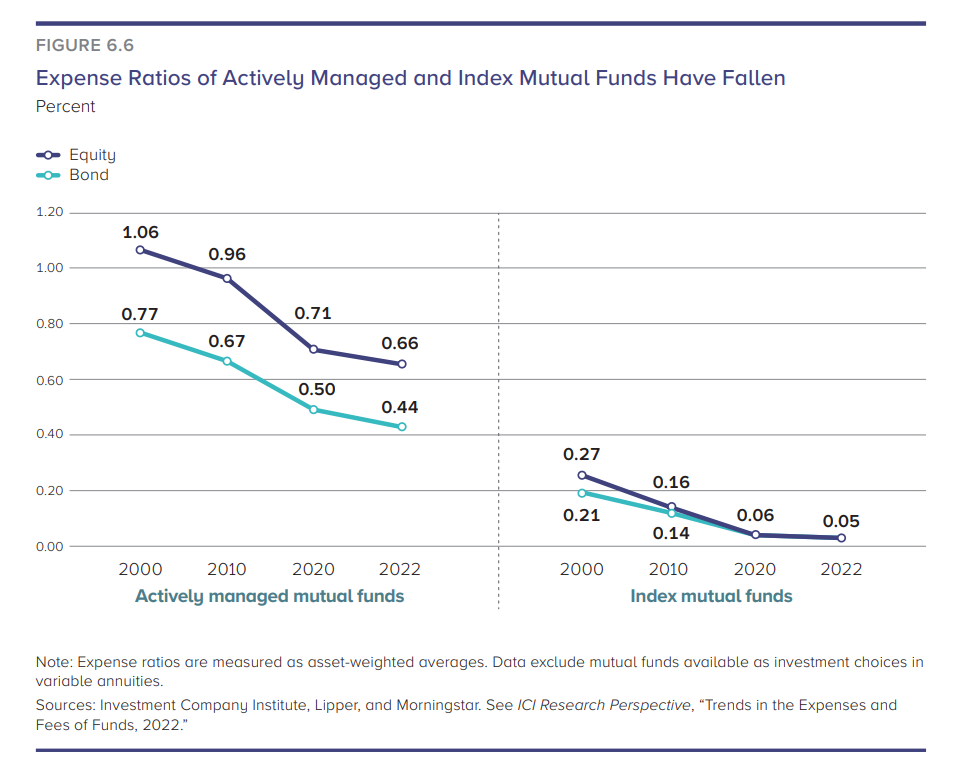

The business of robo-advisory was only possible because of the emergence of cheap investments, such as index funds and ETFs. Most robo-advisors exclusively use ETFs in their asset allocation models because they are much cheaper than active mutual funds. For example, by 2008, the average expense ratio of index ETFs and funds was under 0.15%, compared to the 1.5%+ charged by active mutual funds.

ETFs become popular for a couple of reasons:

One: 2008 crisis and increased competition

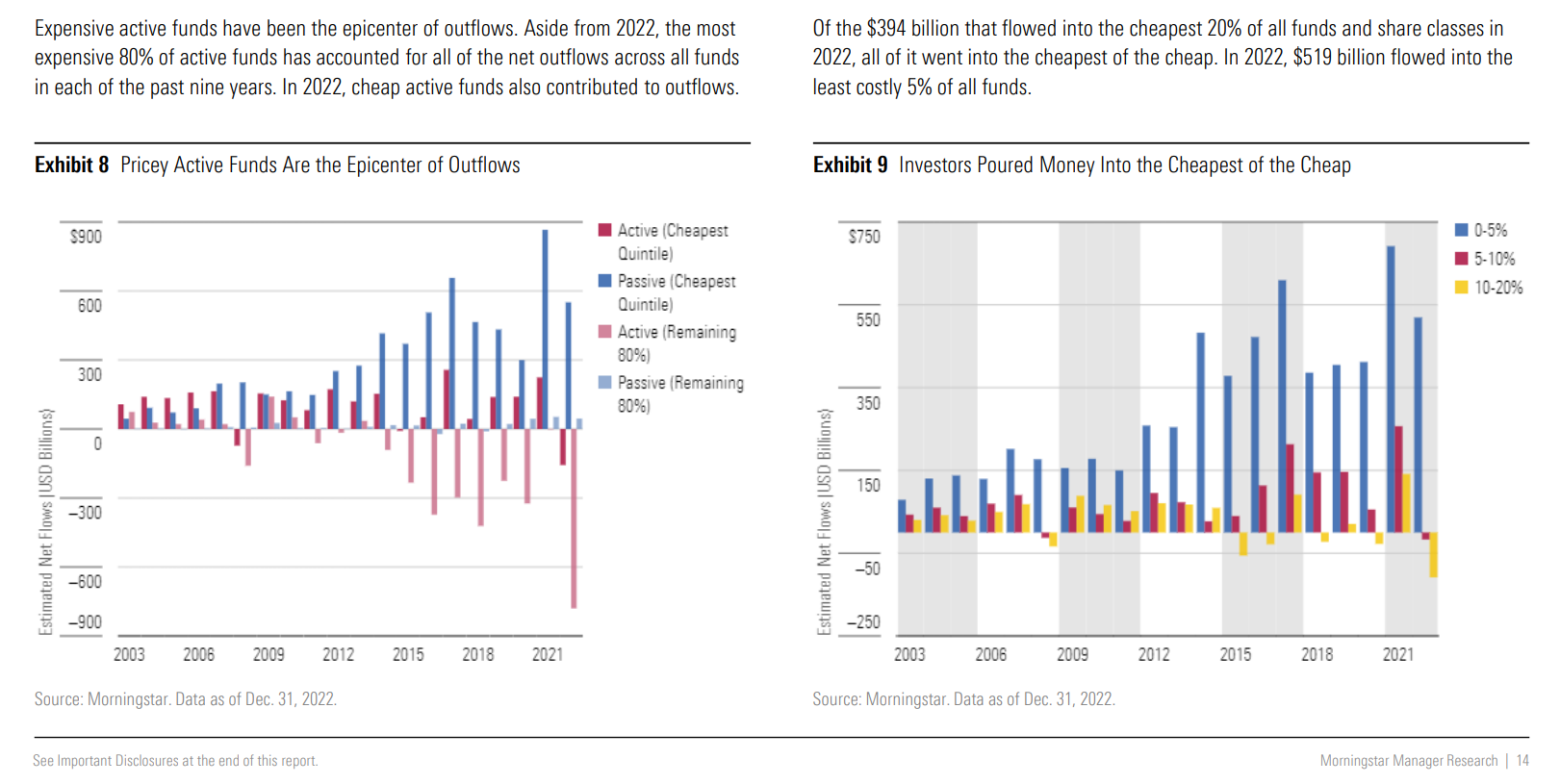

The 2008 crisis was a tipping point for a lot of investors, because they realised their investments were terrible. Most of their money, at that point, was in active mutual funds sold by brokers and distributors. The popularity of personal finance apps and better reporting from brokers made it easier to measure portfolio performance. The revelation that costly active funds were grossly under-performing cheaper index funds led to a shift away from costly active mutual funds and into cheap index funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs). In all, this was a $2–3 trillion dollar shift, and 2008 was its inflection point.

Source: Morningstar

This shift from active to passive investing led to increased competition among asset managers and brutal fee wars. This caused sharp fee compression. In the end, investors were the winners.

Source: ICI

By 2008, thanks to the increased competition among asset managers and discount brokers, ETFs had become much more popular.

Two: Introduction of qualified default investment alternatives (QDIAs)

In the US, the most popular way people save for their retirement is through workplace retirement plans, or 401K plans. The way it works is that a company offers a menu of investments for employees to pick and choose from. The companies that offer these have a fiduciary duty towards their employees. Employers are held liable if they offer terrible investments. Since most companies don’t have the ability to choose investments, the default options they provide are safe investment options like cash investments to avoid getting sued.

To reduce the risk that employers faced, the US Congress introduced a new regulation allowing for certain default investments that provided legal immunity to employers. These defaults were either target date funds or balanced funds. More often than not, target date funds were fund-of-fund wrappers (FOFs) with index funds and ETFs inside them, which played a key role in the popularity of index funds. This development didn’t directly contribute to the emergence of advisors at first, but it created a halo effect around the size and popularity of index funds and contributed indirectly to the popularity of robo-advisors. The direct impact of this regulatory change on robos would emerge much later in the story.

The 2008 crisis

The biggest fallout of the 2008 crisis was a profound loss of faith in the financial system, especially banks. By some measures, trust in financial institutions in the advanced economies has never recovered from the high watermark of 2008 [1, 2]. The 2008 crisis was a tipping point for a lot of social, political, and economic trends. Take any major social, cultural, economic or financial trend in advanced economies from the last decade and a half and you can see the fingerprints of the crisis.

The first robo-advisors were launched at a time when the post-crisis politics were still playing out in the US. In 2011, the Occupy Wall Street (OWS) moment started as a protest against rabid capitalism, rampant inequality, austerity and twisted greed on Wall Street. The protest started in New York and soon spread across Europe. It’s against this backdrop of deep distrust in traditional financial institutions that the first robo-advisors, like Wealthfront and Betterment, started. They channelled the popular discontent against the traditional financial system. The same was the case for other fintech companies from the era, like the broker Robinhood which started in 2013 – the Occupy Wall Street movement is an explicit part of its founding myth.

Financial advisory: The rise of robots

Robo-advisors are the latest avatars of advisory platforms that have been two decades in the making. The predecessors of today’s robo-advisors popped around the 2000 dot-com bubble.

Wealthfront is often referred to as the first robo-advisor. It launched in 2008, but started its life as a social investing platform for retail investors. It then pivoted to having external managers manage wealth for others, and then finally to the automated robo-advisor as we know it as today, in 2011. This wouldn’t be the last time Wealthfront pivoted, as we will see later.

Betterment also started in 2008, but it officially launched in 2010. Betterment railed against brokers and advisors, claiming that they were overcharging and delivering very little value to investors. They started with a fee of 0.90%, which fell to 0.35% by 2012. Soon, dozens of other robo-advisors had cropped up. Personal Capital started in 2009 and is often called a robo-advisor, but it really isn’t one, since it always had human advisors. LearnVest started in 2009 as well, and it too had human advisors. FutureAdvisor started in 2010.

The sales pitch of robos was that human advisors, who controlled trillions in assets, were ripping off investors by charging 1% for sub-par advice, while they offered better and cheaper portfolios for about 0.25%. This was possible, in no small part, due to index ETFs getting cheaper and cheaper. Soon, generic puff pieces and consultant reports followed, claiming that robos could emancipate the mismanaged trillions and make human advisors obsolete.

VCs took notice, and they wanted a piece of the action. This was a time when VCs wanted a piece of everything. Much of this has to do with the economic backdrop of the 2010s. Interest rates had been slashed to zero, and large institutions like pensions and endowments were taking higher risks to compensate for the low returns on bonds. A lot of this money moved into private equity and venture capital. Soon, robos around the world started raising large rounds.

| Robo | Total funding (in US$ million) |

| Wealthfront | 205 |

| Betterment | 335 |

| FutureAdvisor | 22.70 |

| SigFIg | 119.50 |

| Personal Capital | 215.30 |

| Jemstep | 10.50 |

| Ellevest | 153.40 |

| Nutmeg | 152.55 |

| Wealthsimple | 712.38 |

The original sin

This was the value proposition of robo-advisors:

- Low-cost access to diversified investment portfolios, at a fraction of the fees human advisors charged.

- Easy on-boarding and investing journeys compared to the cumbersome paper-based processes of human advisors.

- Cool tools and features like automatic re-balancing, tax loss harvesting, and fancy dashboards.

The pitch that robo advisors would replace human financial advisors never made sense. Fundamentally, the robos didn’t give a whole lot of advice. They were simply managing investments. They offered diversified portfolios based on some standardised risk assessments. That’s it.

There’s more to financial advice than just building portfolios. A good advisor gives you a comprehensive plan for your entire financial life. They advise clients on everything from taxes to trusts, from wills to retirement planning.

Robo advisors didn’t touch this business. The market they disrupted was of brokers and distributors that sold products for commissions. They were competing against those who overcharged for and sold horrible products, rather than investment advisors.

At a broader level, the technology that powered robos was also nothing new. Financial advisors have been using turnkey asset management platforms (TAMPs) that offer investment models, re-balancing, and tax loss harvesting for a long time.

The empire strikes back

There was some concern among financial advisors about robos at the start. By 2014–15, however, it was apparent that they weren’t a threat. Robo-advisors weren’t competing with human advisors, but rather with other self-directed brokers, D-IY investing platforms and, to a certain extent, asset managers. They were a bigger threat to the likes of Charles Schwab, TD Ameritrade and Fidelity than human advisors.

2015-16 was the period when these giants woke up. The lifeblood for asset managers and brokers are flows. The incumbents saw the writing on the wall: robos could potentially move flows. Charles Schawb launched its in-house robo, Intelligent Portfolios. Soon, Vanguard launched Personal Advisor Services (PAS), which paired the automated investing solution with the option of human advisors (CFPs). Fidelity followed suit with its own robo, called Go. Within months, both Schwab and Vanguard had gathered billions in their robo-advisory offerings.

Behind this was also a fair amount of FOMO. Blackrock acquired FutureAdvisor for $150 million when the AUM of the robo was just $600 million. Insurance giant Northwestern Mutual acquired LearnVest for $250 million. In 2016, Invesco acquired Jempstep. ETF specialist WisdomTree invested in AdvisorEngine, a B2B robo. This trend of asset managers acquiring robo advisors would continue into the 2020s, with Principal and Franklin Templeton, among others, adding their own robo.

In my view, this was a really good strategy on the part of the asset managers and brokers. For these companies, one of the biggest problems is distribution and customer retention. Robo-advisors offered a partial solution to both the problems.

Pivots

By 2016, the hype around robo-advisors had deflated. The wishful visions of disruption and the addition trillions in assets never materialised. Robo-advisors realised that they had overestimated their usefulness, while VCs processed the fact that they had misjudged both the model and the opportunity size. Soon, a series of pivots followed.

In a bid to diversify its revenue base, Betterment introduced human advisors that offered advice on taxes, savings, and retirement planning for an add-on fee of 0.15%. It also ventured into the retirement plans (401k) business in 2016. In the same year, it re-branded its white-labelled robo-advisory service from Betterment Institutional to ‘Betterment for Advisors’. Yep, Betterment, the loudest robo railing against the greed of advisors, was now offering a robo to advisors.

Similar to Betterment, other robo-advisors began targeting the 401k space. Like QDIAs more generally, one of the most popular investment options on these 401k robo-advisors was target date funds.

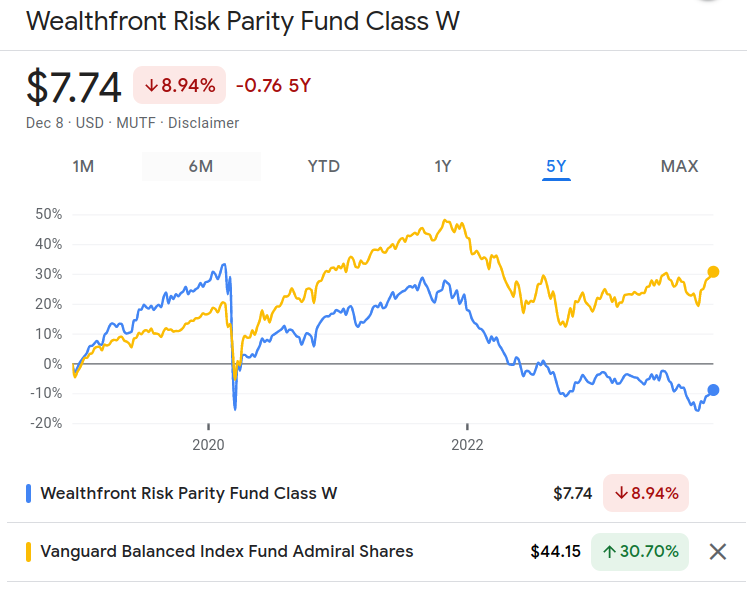

Wealthfront, too, went through a series of pivots. Unlike Betterment, it stuck with a B2C strategy, but it kept searching for higher revenue opportunities. It soon started offering high-yield savings accounts, direct indexing, stocks, crypto, and a disastrous risk parity fund that may have cost investors hundreds of millions.

The same was the case with other robo-advisors. They struggled to gather AUM, and many either pivoted or shut down.

Revenge of unit economics

The math behind robo-advisory never added up. These companies had raised hundreds of millions and were nowhere close to making money. The first challenge was that financial services was a low-trust business, especially for the ‘Occupy’ generation. The high-net-worth investors wouldn’t go to robo-advisors, and that left the robos competing against smaller retail investors. Morningstar summed up the brutal economics of the robo-advisor business in 2019:

Robo-advisors in the U.S. have faced three main challenges: high client acquisition costs, ongoing costs of servicing clients, and low revenue yield on client assets. The advertising cost per account acquisition at robo-advisors is approximately $300 per gross new account and $1,000 per net new account. At their presumably low operating margin after they become profitable, the payback period on advertising costs can be more than a decade. Expanded service offerings and higher revenue yields dramatically reduce the operating expense ratio and client asset hurdles to reach the goal of profitability. We estimate the break-even point for robo-advisors that sustain a 50bps revenue yield could be $15 billion-$25 billion of client assets, 38%-63% lower than the break-even point for a robo-advisor that charges 25 bps. Not surprisingly, many robo-advisory firms are still unprofitable.

Prelude to the end

As morose as it sounds, COVID-19 was the best thing to have happened to the fintech industry. Most financial services companies saw a massive influx of new users. Robo-advisors around the world, however, were left by the wayside. One reason was that people were looking for entertainment and not sane, boring things like the low-cost, diversified portfolios offered by robo-advisors. This is why Dogecoin accounted for 60% of Robinhood’s crypto revenues in 2021.

Robo-advisors missed two parallel trends starting in 2020, which sealed their fate:

- There was a mega retail investing boom. A generation of retail investors piled into everything from exotic nonsense like crypto, penny stocks, call options, or fractional art to more boring things like ETFs and index funds. The number of boring investors, unfortunately, was less than the number of people that wanted to do crazy stuff.

- Special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) emerged as one of the most prominent speculative investment vehicles on Wall Street. They were essentially backdoor IPOs. Many useless, scammy companies went public through SPACs. Not that robos are necessarily scammy, but I was 100% sure SPACs were the only way VCs would ever cash out their investments in robo-advisors.

The markets’ speculative fervor continued until 2022. In response to this massive demand, Betterment, Wealthfront and Wealthsimple (Canada) began offering speculative options like direct stock investing and crypto. This was a remarkable U-turn for platforms that had preached sane investing in diversified low-cost ETFs for the long-term. But they were too late. Speculation deflated violently in 2022 as Fed interest rates rose. The likes of Robinhood had attracted most of those that wanted to do crazy things during peak demand. By the time the robos wisened up, there was nobody left to service.

The trend of SPACs also came to a spectacular end with fraud and lawsuits. Despite several rumours of SPACs looking at both Betterment and Wealthfront, a deal never materialized. In a fortunate turn of events, Wealthfront managed to convince UBS to acquire it in January 2022 for $1.4 billion. It was probably the best deal that Wealfront could’ve hoped for. But, in a cruel twist of fate, UBS pulled out of the deal in September 2022 as economic conditions worsened.

If you step back a little, the road had grown tough for robo-advisors much earlier. The technology that robos had developed—digital onboarding, automatic portfolio construction, trading, and rebalancing—was pretty good. In many cases, they were much better than the tools available to human financial advisors. So, the advisors’ technology platforms began co-opting robo technology from ~2017, through model marketplaces.

As the name implies, model marketplaces aggregate investment models from asset managers and other advisors. Their pitch is that advisors could use ready-made models and save the time they would spend on investment management. All advisors had to do was select a model, implement the model in client accounts and re-balance periodically. They could spend the time thus saved on financial planning. Robo-advisors made a mistake by betting on B2C. They should have sold their tools to human advisors. In an alternate universe, human advisors could’ve been the biggest users of robo-technology.

Bad robo!

Meanwhile, robo-advisors also gained notoriety for using dodgy tactics. Schwab offered Intelligent Portfolios for free because the underlying funds in the portfolio were Schwab’s own funds. It also had a higher cash allocation, ranging from 12-25% in its portfolios. This cash was swept into Schwab’s own bank, and the interest wasn’t passed back to the investors. This was a terrible deal for investors.

The SEC started investigating, and Schwab settled by paying a massive $187 million in 2022. Over the years, both Betterment and Wealthfront have also paid millions in fines for failures of their tax loss harvesting features. Regulators around the world have raised concerns about the quality of advice delivered by robo-advisors and their compliance with regulations.

State of disunion

Hundreds of robo-advisors around the world, like MoneyOwl, Bloom, Hedgeable, Investec, SmartWealth, Prospery, TradingFront and WorthFM, have shut down. A few others have been acquired at fire sale prices. The last notable deal was the acquisition of UK robo-advisor, Nutmeg by JP Morgan.

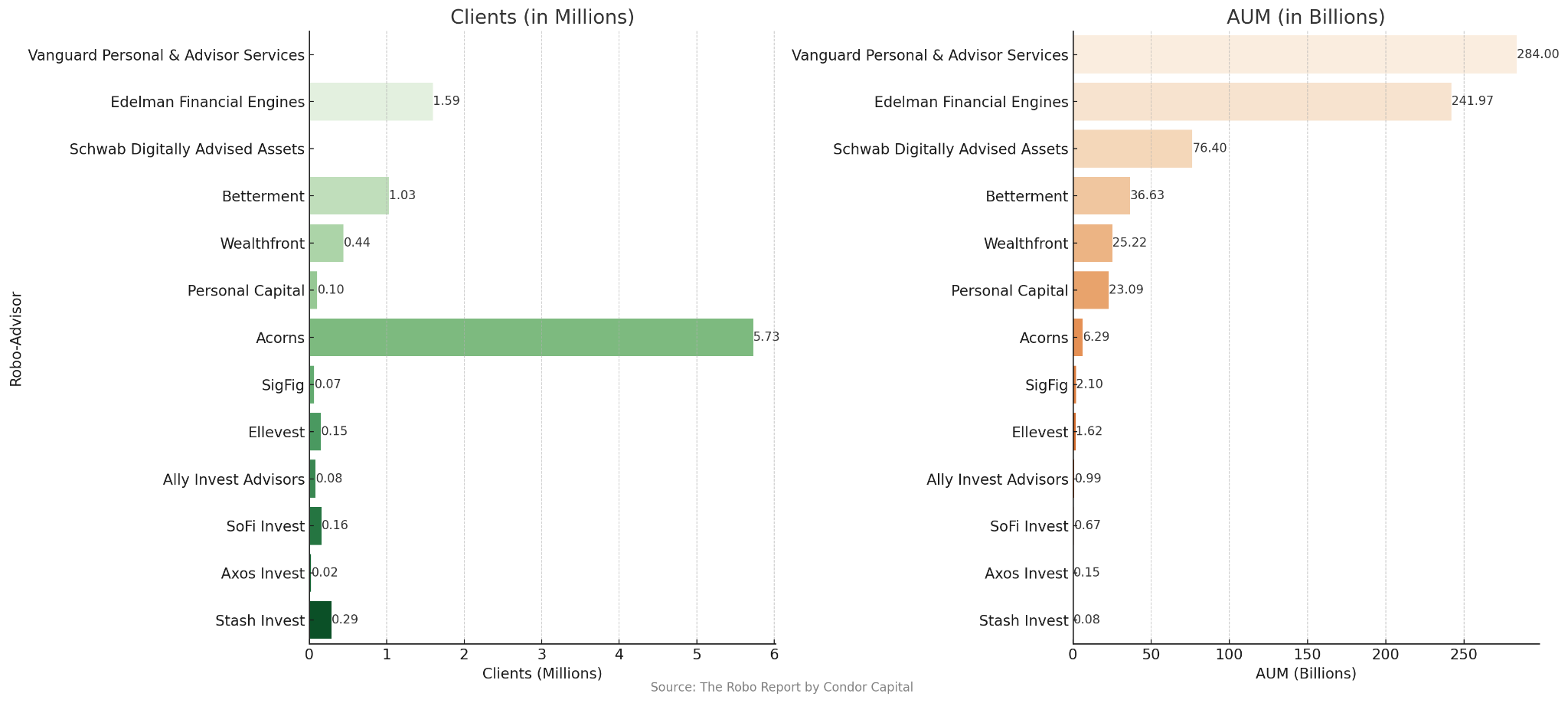

The original robo-advisors – Wealthfront and Betterment – are still around. Their original founders have stepped down, however, and there are new hands at the helm. The AUM of Wealthfront is $50 billion. Betterment manages around $40 billion. At 0.25% of fees, they would make between $125 and $100 million in revenues. For comparison, the AUMs of Vanguard PAS and Schwab Intelligent Portfolios are at $280 billion and $76 billion. In 2019, Schwab added a paid tier of human advisors at $30 a month, along with a free tier.

Having said that, I have my doubts about the way robo-advisors calculate their AUM. Both Wealthfront and Betterment offer cash accounts in partnership with banks. They may be counting cash assets as AUM. Their investment assets, by themselves, may be much lesser. They do earn revenue on cash accounts too: the difference between the rate a banking partner gives them and the rate they pass on to the end investors. Since rates are high today, these revenues are meaningful. If they head lower, however, the picture changes.

Blackrock got rid of its $150 million robo. The robo efforts of other asset managers and brokers like Invesco, Principal, Franklin Templeton, SoFi, etc. are failures as well.

Robo advisors in India

Let me be a little petty: India has never really had any true robo-advisors. At best, we’ve had semi-robo-advisors. The reason is simple: robo-advisory implies automation, and given our regulations, apart from investing, nothing else can be automated – like re-balancing, tax loss harvesting, etc. All such transactions require customer consent.

Setting that aside, however, we also never really had a good semi-robo until a few years ago. Many platforms that called themselves robo-advisors were just DIY execution platforms. The Indian markets were way too small when the fintech hype was at its height in the US around 2015. At that point, there were barely 50–60 lakh unique investors in India. And so, the craze for robos never truly caught on.

Today, there are a few full-fledged semi-robo-advisors in India, but they face the same challenges as their US counterparts: from high CAC to low-ticket investors.

Is robo-advisory a feature?

Here’s my thesis: a lot of fintech companies are features, not businesses. It was the same with robo-advisory as well. Let me explain:

Robo-advisors just recommend a diversified portfolio based on a standardized risk profile questionnaire, which itself is deeply flawed to begin with. Even with investing, robo-advisors never had visibility into the other investments that userss had across other platforms. Without understanding one’s financial life holistically, it would necessarily have major blind-spots.

In the US, robos tried to solve this with data aggregators like Yodlee and by allowing rollover of investment accounts, but they were partial solutions at best. In India, platforms integrated CAS statements, which solved for the visibility of mutual funds but not stocks and other investments.

The second issue was that investing is just one small part of overall personal finance. Other things like insurance, taxes, wills, etc., are far more important. Robo-advisors weren’t built to solve these issues. Many added a human layer and became hybrid robos but they were still stuck with an investment-first approach.

Also, evidence shows investors prefer human advisors, which meant that robo-advisors would never appeal to rich and sophisticated investors. This left them with small retail investors, who tend to have smaller investments and high customer acquisition costs. Moreover, many retail investors did not crave investments – they wanted entertainment – and other brokers like Robinhood offered plenty of entertainment, in the form of zany, volatile investment products like crypto.

All this means that robo-advisory was only a feature. Look closely at the ones that have succeeded; it’s Schwab, Vanguard, and Fidelity. All these companies were trillion-dollar giants before adopting robos, and used robo-advisory as a distribution and customer retention tool. The biggest problem for asset managers is customer acquisition, and a robo-advisory feature or layer was a no-brainer because it removed the anxiety and decision paralysis for new investors—the asset manager they had heard of and preferred was now telling them what to do.

This incidentally made robos a customer retention tool as well. Many investors drop out of their investment journeys because of their own poor behavior. They buy high, sell low, and do all sorts of dumb things. Robos offer some basic advice which stopped investors from doing dumb things. This meant better customer retention for these brokers and asset managers.

What comes next?

My crystal ball is as fuzzy as yours, but life looks tough for robo-advisors. Many of them have taken massive VC investments, and sooner or later, their investors will demand exits. The best-case outcome for a robo-advisor was to be acquired by a large financial services company, but market conditions have taken that option off the table. The robo-advisory market was crowded, with too many players trying to do the same thing to attract the same limited pool of customers. All that stupidity has now washed away, with the smaller ones getting acquired in distress sales or shut down.

Right now, the only surviving players are the ones with large scale, like Wealthfront, Betterment, and Wealthsimple. Betterment recently changed its pricing on smaller accounts under $20,000 to a $48 annual fee. It’s a clear move to get rid of unprofitable small accounts. It’s also betting big on its institutional retirement and B2B robo business. Wealthfront is still looking for a tipping point. Wealthsimple, Canada’s biggest robo with about $18 billion in AUM, has followed a similar trajectory. It started as an automated robo offering low-cost funds, but has now moved to stocks, crypto, and even private equity.

Robo-advisory is not really a thing in India yet. It’s also very hard to build a standalone robo-advisory service in India, given the high customer acquisition costs and low ticket sizes. Even if you somehow get past those challenges, the regulatory friction and hurdles are a nightmare. To be a robo advisor, you need to get an RIA license, which is among the most compliance-intensive licenses in India. Then you have the fact that, in India, you cannot automate rebalances, tax loss harvesting, etc. Unlike US robos, Indian robos also cannot touch customer funds; they have to rely on bank mandates.

Where does that leave us? The next successful investing platform will likely come from existing financial services companies. Even for all the existing semi-robos and DIY investing platforms in India, an acquisition is the best-case outcome.

Very detailed pretty accurate picture of the state of Robo-advisory. Having been a participant offering services in this space, the timing of all solutions and the challenges they faced are pretty spot on. A few things that should be marked in bold for all future reference

– Investment advisory is not the same as financial advisory

– Given a lot of Indian advisory is left to customers taking action, customer behaviour is at fault for not sticking to fundamental principles of disciplined investing

– Time and again it’s proven that in wealth management, only product manufacturers and FnO brokers make money.

A lot of things have changed in the past decade though. It has become fairly possible to avoid blind spots by aggregating all use accounts. Maybe with the use of AI agents, discharging advice to a small portfolio user base is possible too. But time and again, CAC and customer retention have been the bane of a digital wealth management solution and I expect that to still be a relevant hurdle to cross for any future offering.

Zerodha’s blogs are highly opinionated.

This is a knowledge curse every big company eventually falls into.

Happens with every new change.

I’m happy Groww is proving them wrong in every aspect.

Please give way to innovation and avoid opinions.

A very well researched document. Having come from an Investment Banking Technology background, I have long been fascinated by the potential of such a platform, but never found one that truly satisfies my requirements.

I have used quite a few of them in India and abroad, and even though they are not perfect, I feel they can play an essential part in wealth management and retirement planning.

If someone can bootstrap such a platform – without any VC money – and distribute the same organically, I think they will make a come back once again. …And that’s precisely I am planning to do! If anyone is interested, let’s join hands!