It’s the economy, stupid! Less energy, more electronics

We love India Data Hub’s weekly newsletter, ‘This Week in Data’, which neatly wraps up all major macroeconomic data stories for the week. We love it so much, in fact, that we’ve taken it upon ourselves to create a simple, digestible version of their newsletter for those of you that don’t like econ-speak. Think of us as a cover band, reproducing their ideas in our own style. Attribute all insights, here, to India Data Hub. All mistakes, of course, are our own.

Exports fall, imports fall faster

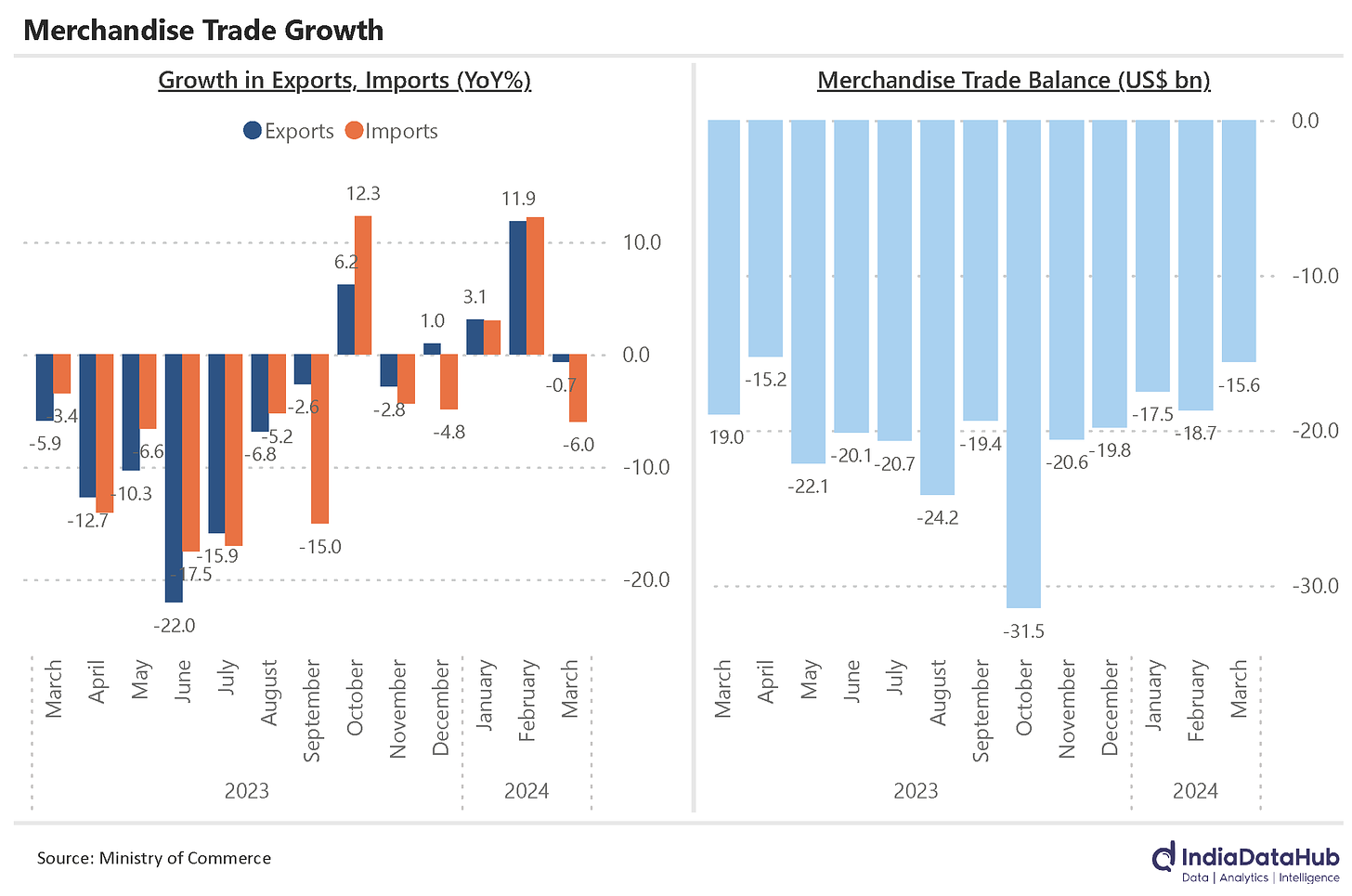

There are two bits of news on how much we’re trading with the world. One, we’re selling less. Two, we’re buying much less. Here is the math:

- Our merchandise exports this March were 1% lower than in March last year. (In contrast, they had grown in the double digits back in February)

- Our merchandise imports declined by 6% over the same period.

Square these off, and our merchandise trade deficit (imports minus exports, that is) have dropped. In fact, they fell below US$ 16 billion for the first time in the better part of a year – since April 2023, that is. Add services to the picture, and we’ve probably held our overall trade deficit to under US$ 1 billion over the month.

All this shows up in how the Rupee has performed in international markets. We’ve touched on this dynamic before, but let me quickly bring you to speed.

All this shows up in how the Rupee has performed in international markets. We’ve touched on this dynamic before, but let me quickly bring you to speed.

When Indians buy something from abroad, they discard Rupees in favour of a foreign currency. The more they do so, the more readily Rupees are available on currency markets. Equally, when people from abroad buy something from India, they seek Rupees. The more they buy, the more Rupees leave currency markets. Imports and exports, therefore, pull at the price of the Rupee from different directions. Its final price is a question of how scarce it is on these international markets.

In a month like this, when Indians are buying a lot less from abroad, less of the Rupee has reached currency markets. This relatively scarcity is driving up its price.

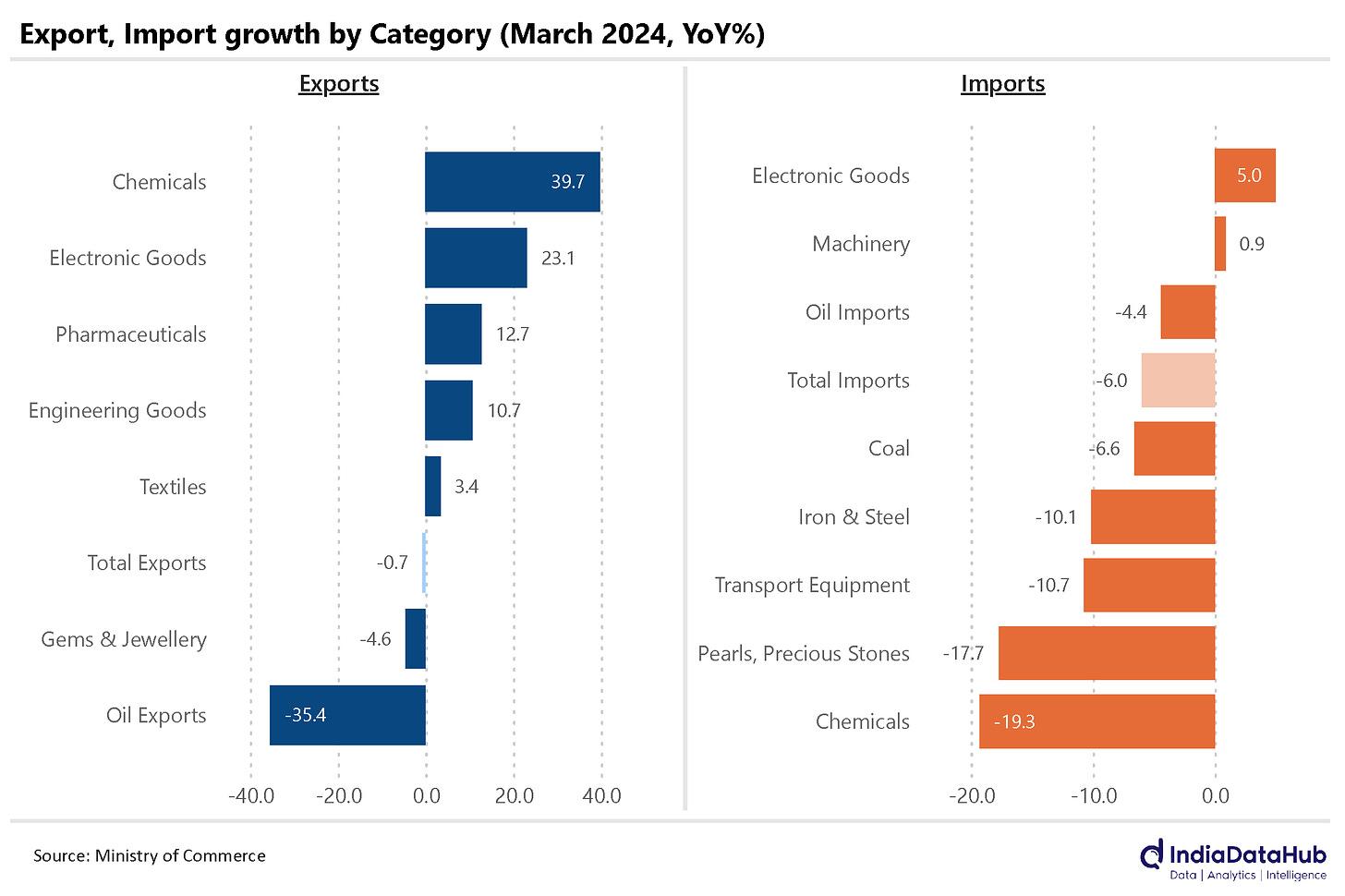

Why are we selling less, though? There’s a simple answer: our petroleum exports have crashed. Other things have done fairly well, in fact:

- Excluding petroleum products, our exports have grown by 8% this March, compared to March last year.

- Indian chemical exports grew by almost 40% in this period.

- Electronics exports grew by 23%, year on year.

- Other sectors, like pharmaceuticals and engineering exports, also saw double-digit growth.

Our imports, on the other hand, have declined across the board. For one, our petroleum imports dropped by 4%. But exclude these, and our imports still fell by 7%. The fall came from across sectors, as this graph will tell you:

India PLIes its electronics trade

In all, over the last financial year, India exported 3.5% less goods than we did in the year before. There was one stand-out exception, though: electronics.

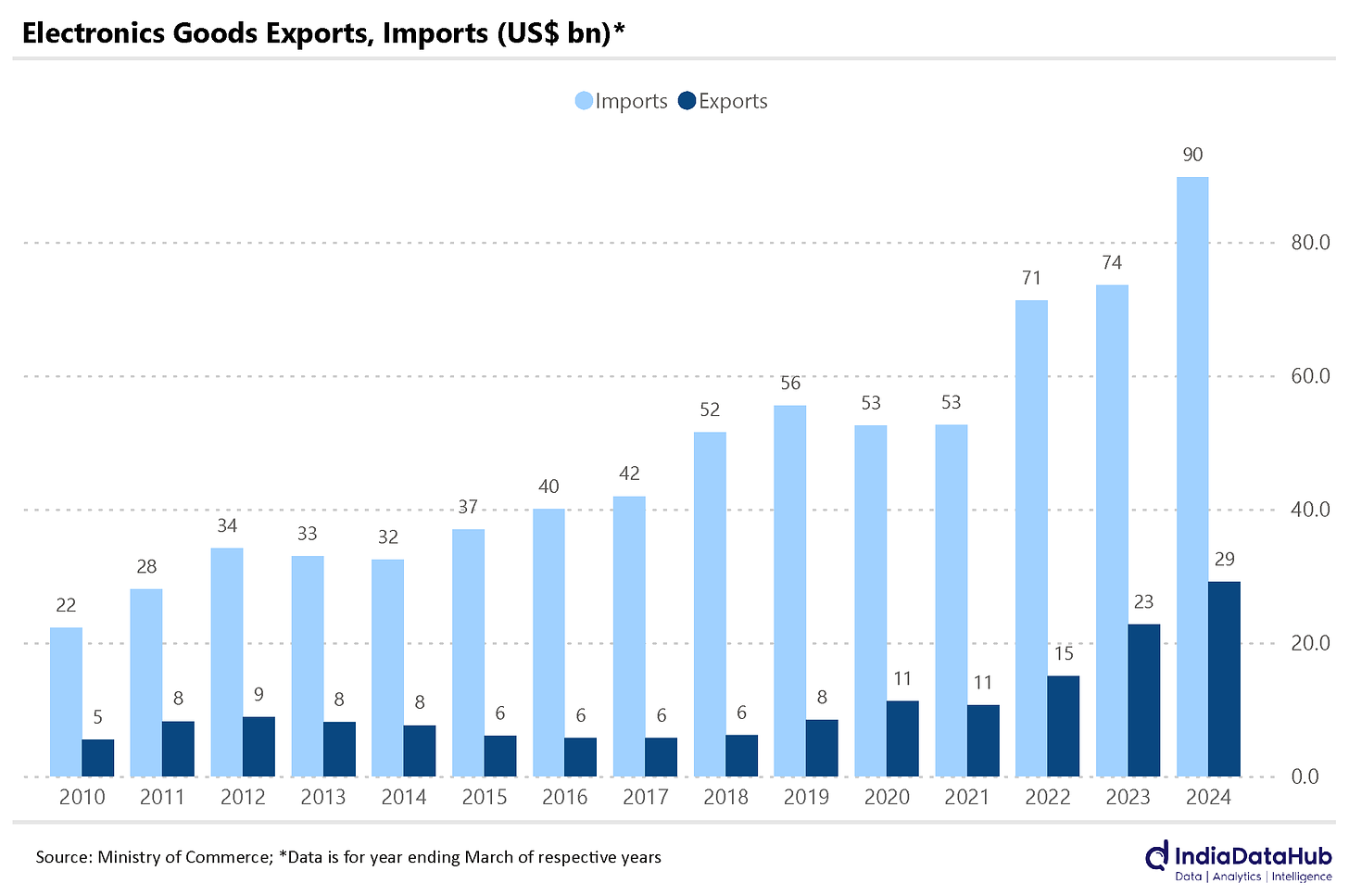

Our electronics exports last financial year were 28% higher than in FY 2023, well above the 22% growth in our imports. This is part of a multi-year trend; our electronics exports have grown faster than our imports for five of the last six years. In the last five years, our exports have tripled.

Amazing, right!?

Almost, though not quite. Let’s sober down for a moment and look at the graph below. There’s one thing all these percentages hide: our electronics exports are a mere fraction of our electronics imports. Last year, for instance, our exports were less than a third of our imports. That’s how it’s been for a while. If our exports increase by $1 billion, that’s a substantial expansion of what we sell. If our imports grow by as much, it’s hardly a blip.

That spot of pessimism notwithstanding, there’s definitely a long-term shift in our electronics trade.

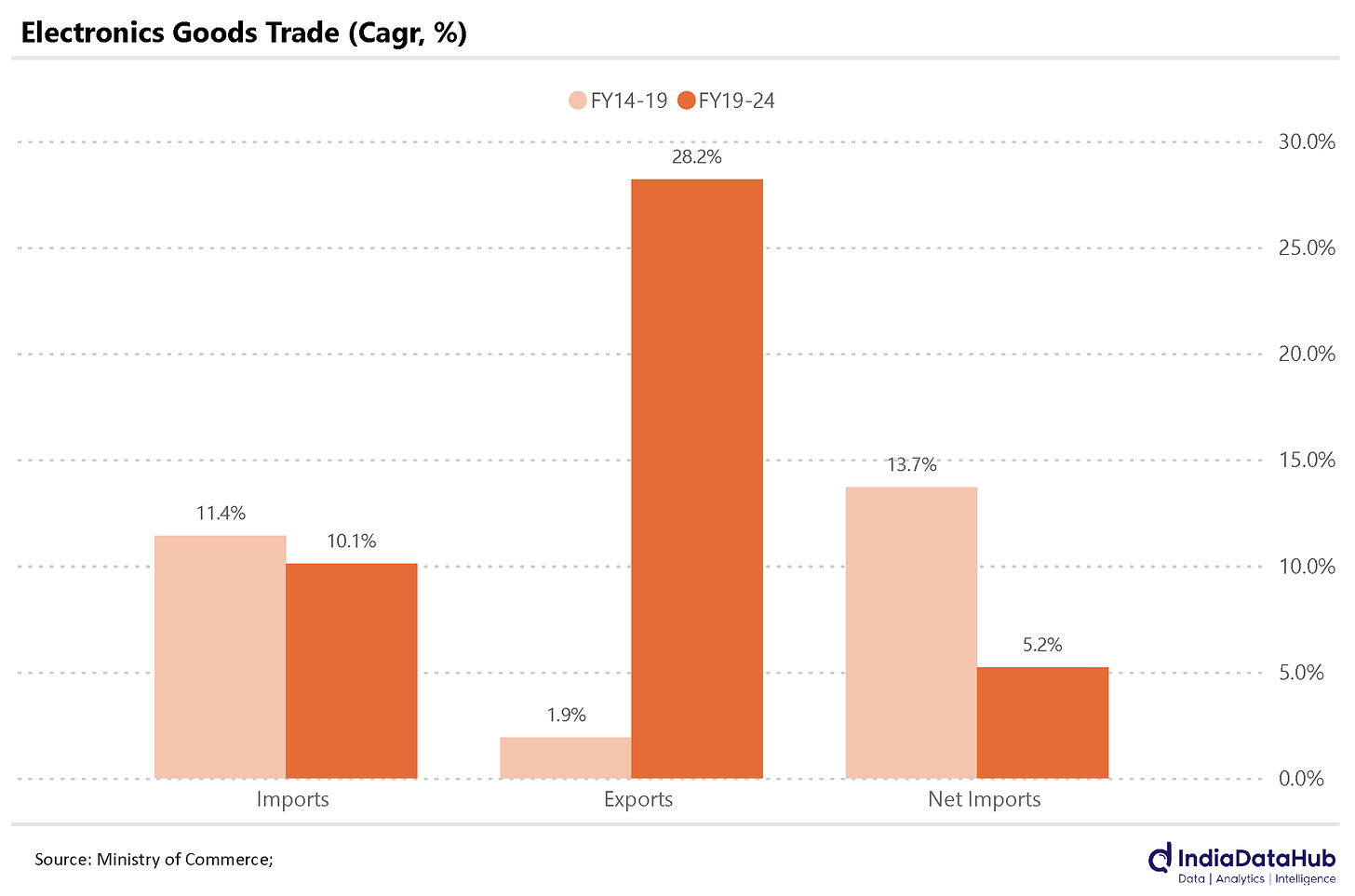

Between FY 2014 and FY 2019, our electronics imports were growing by 11.4%. That has fallen slightly since. Over the subsequent five years, our imports grew at a slower pace of 10.1%. It’s a drop, sure, but only a marginal one. Nothing to get too excited about.

Add our exports to the mix, however, and things change starkly. Between FY 2014 and FY 2019, our net imports (that is, imports minus exports) grew at 14%. In the five years thereafter, however, their growth has dropped precipitously: to a mere 5% per year.

In essence, while our electronics imports have grown at a fair clip, our exports have risen far more dramatically. While, in absolute terms, our exports still lag our imports, they’re catching up fast. We owe this rise, arguably, to industrial policy: the ‘production-linked incentives’ for the electronics industry, in particular, seems to have catalysed a lot of this growth.

Life insurance soars, general insurance sinks

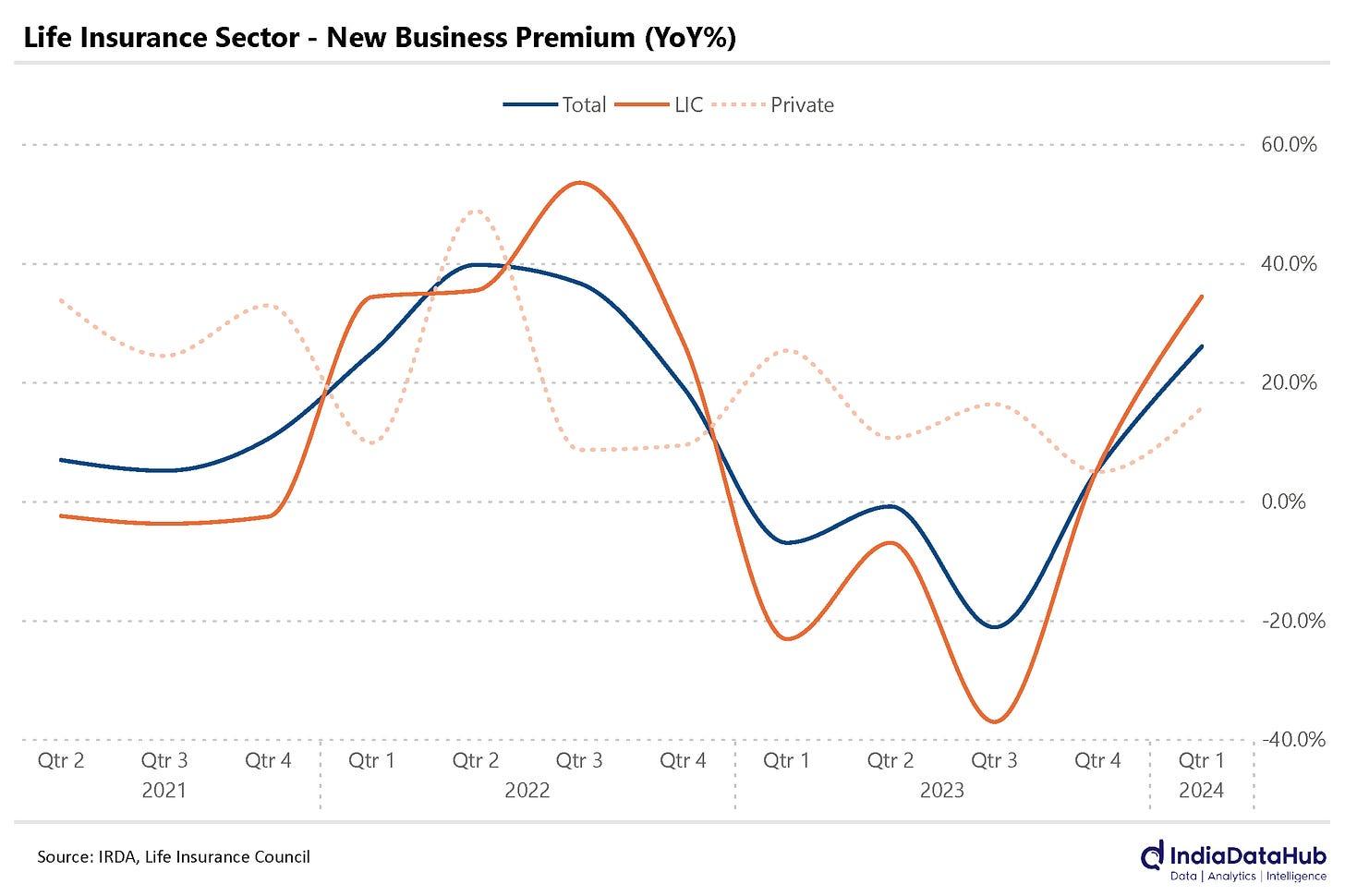

India’s life insurance sector just had a growth spurt. The sector’s ‘new business premiums,’ or all the money they raked in for selling new policies, jumped by 26% in the quarter that ended this March, compared year-on-year. They haven’t grown this fast in any of the last six quarters.

LIC is leading this pack. Its new business premiums jumped by more than a third, year-on-year, for the quarter. The rest of the industry, in contrast, grew by a mere 16%.

There are two ways you can push up new business premiums. One, you can sell more policies. Two, you can charge more per policy. Most of last quarter’s growth has come from the latter – from a rise in premium amounts.

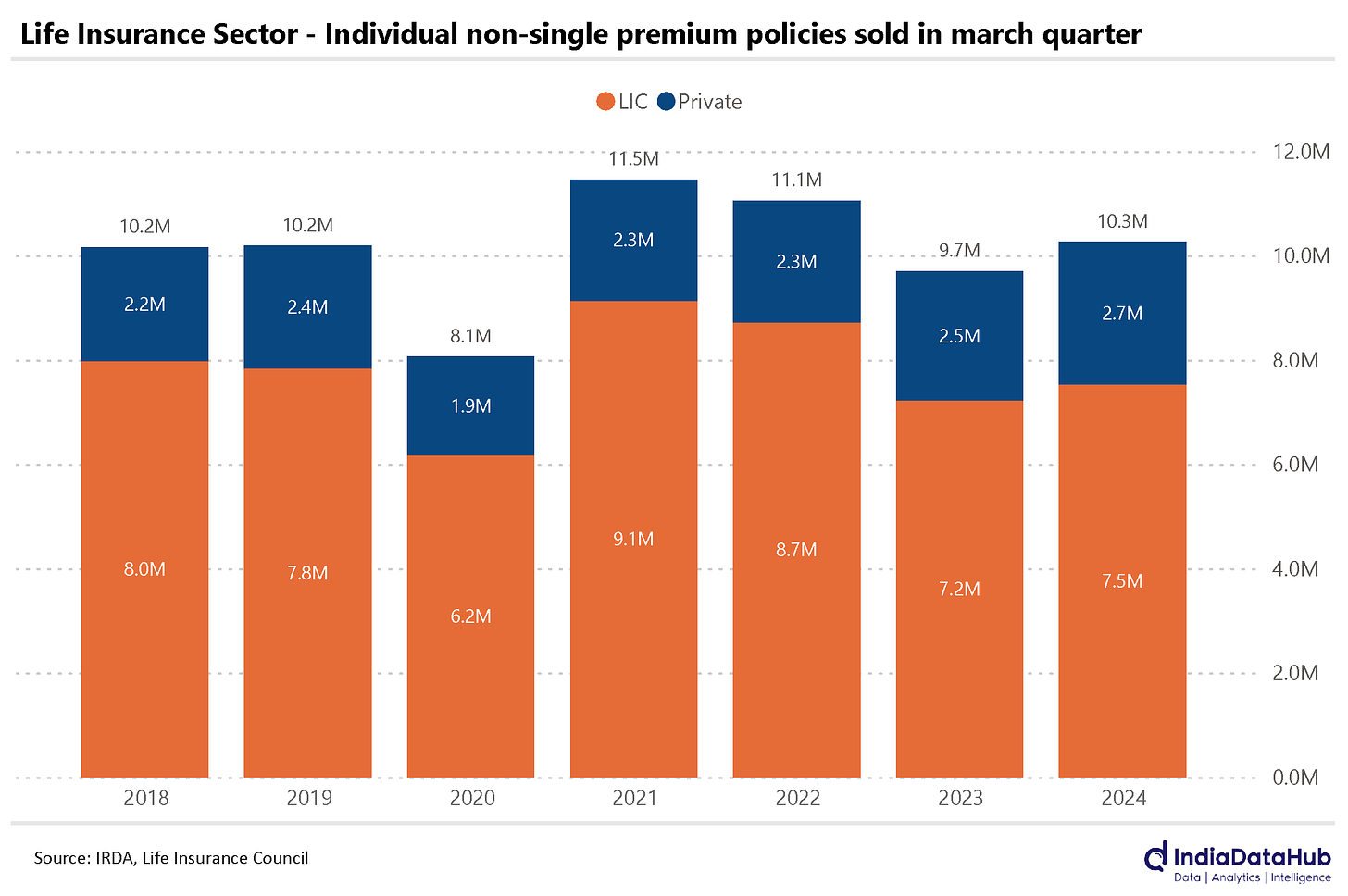

The number of policies, on the other hand, hasn’t risen quite as dramatically. 10.3 million policies, in all, were sold last quarter; 5% up from last year’s March quarter. Sounds neat, I know, but that’s nowhere close to their peak from a few years ago, in the quarter that closed in March 2021. They’re still 10% lower than they were back then.

Once again, LIC’s dominant presence skews the data. Other insurers have grown the number of policies they sell over this period.

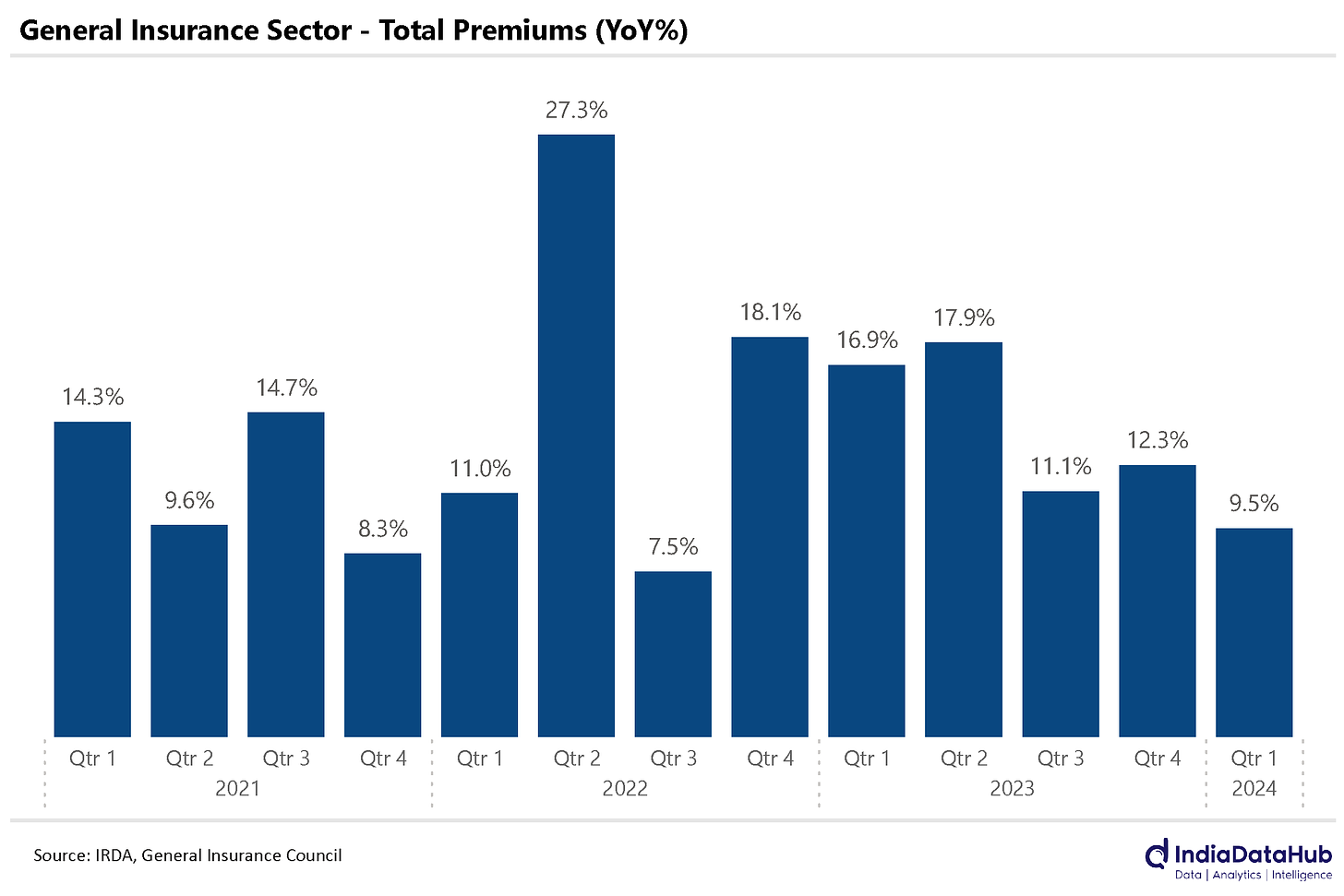

General insurance, on the other hand, is seeing its growth stall. Last quarter, the sector’s premiums grew by a mere 9%, year-on-year: the slowest it has grown in six quarters. This deceleration wasn’t uniform:

- Health insurance, for instance, continued to see healthy growth: in the high teens.

- Motor insurance premiums saw anaemic, single-digit growth.

- Crop insurance tanked, with premiums falling by 15%, year-on-year. This is the weakest performance it has turned in for more than three years.

That’s all for the week, folks! Thanks for reading.