It’s the economy, stupid! Is India working?

We love IndiaDataHub’s weekly newsletter, ‘This Week in Data’, which neatly wraps up all major macro data stories for the week. We love it so much, in fact, that we’ve taken it upon ourselves to create a simple, digestible version of their newsletter for those of you that don’t like econ-speak. Think of us as a cover band, reproducing their ideas in our own style. Attribute all insights, here, to IndiaDataHub. All mistakes, of course, are our own.

The complete jobs picture

Are Indians working enough? Are there enough jobs in the economy to support all our livelihoods? What are we doing well, and where do we need things to get better? As politicians fight and rankle over the state of Indian employment, here’s how the numbers actually pan out.

Let’s begin with the ‘unemployment rate’.

A country’s unemployment rate is a measure of all the people “in the labour force” without a job. That qualifier — that they’re in the “labour force” — is all-important. The unemployment rate doesn’t measure the percentage of our total population that isn’t working. It limits itself to those who actively seek work. By this criterion, you’re only unemployed if you’re out there looking for work, but haven’t found any. If you’d like some work, but are actually just lying around at home, discouraged, instead of applying anywhere — you aren’t part of the labour force, and so, aren’t counted amongst India’s unemployed.

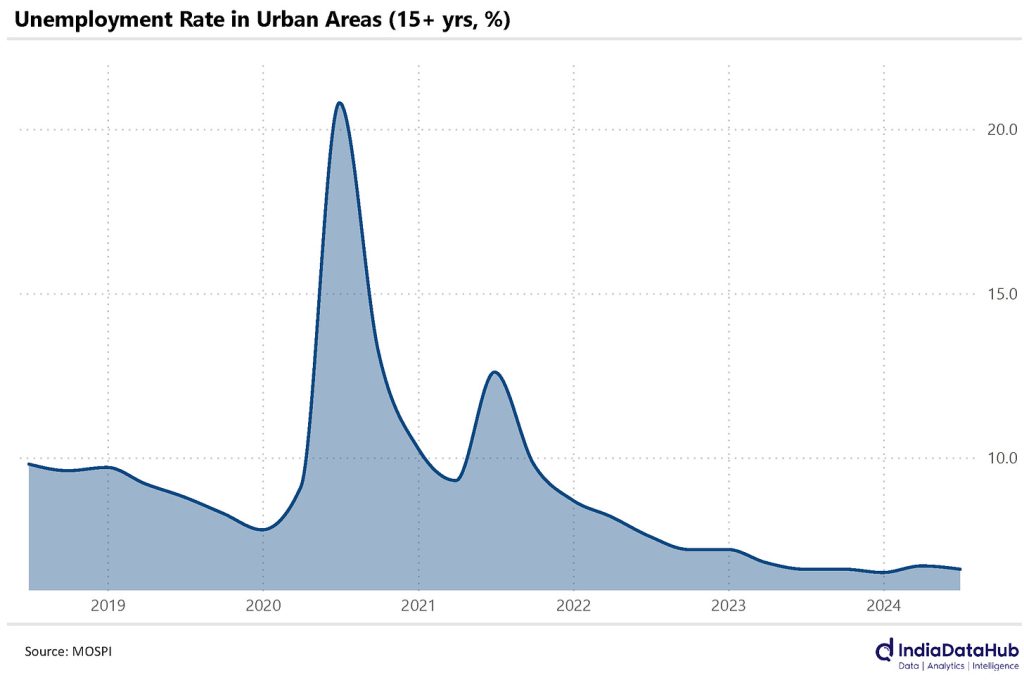

India’s unemployment rate in the June quarter, in urban areas, stood at 6.7%. That’s where it’s been for a while. Our unemployment rate was the same a quarter ago, and it was the same a year ago.

Now, one may be unemployed because of how weak an economy is. But one might also be unemployed for wholly unrelated reasons. If you’ve just started your career, for instance, employers have no reason to trust you, because you barely have a track record to rely on. If you’re moving cities, or industries, you might generally find it hard to immediately land a job. You might have high standards for the work you want to do, and might reject most jobs that come your way because they don’t promise you a sense of personal satisfaction. When someone’s unemployed for natural, non-macro reasons, it’s called ‘frictional unemployment’.

Young workers are hit the hardest by frictional unemployment. That’s when everyone’s trying to prove their mettle, while also trying to find what they really want from their working life. You’re bound to see more unemployment than average in this cohort. But here, too, there’s good news. Over the last year, unemployment among young people (that is, in the age group 15-29) has dropped by almost one full percent — from 17.6% to 16.8%.

With that, let’s take a step back.

Remember how the unemployment rate only measures people within the labour force that don’t have a job? A natural question, then, is: what’s happening to the labour force as a whole?

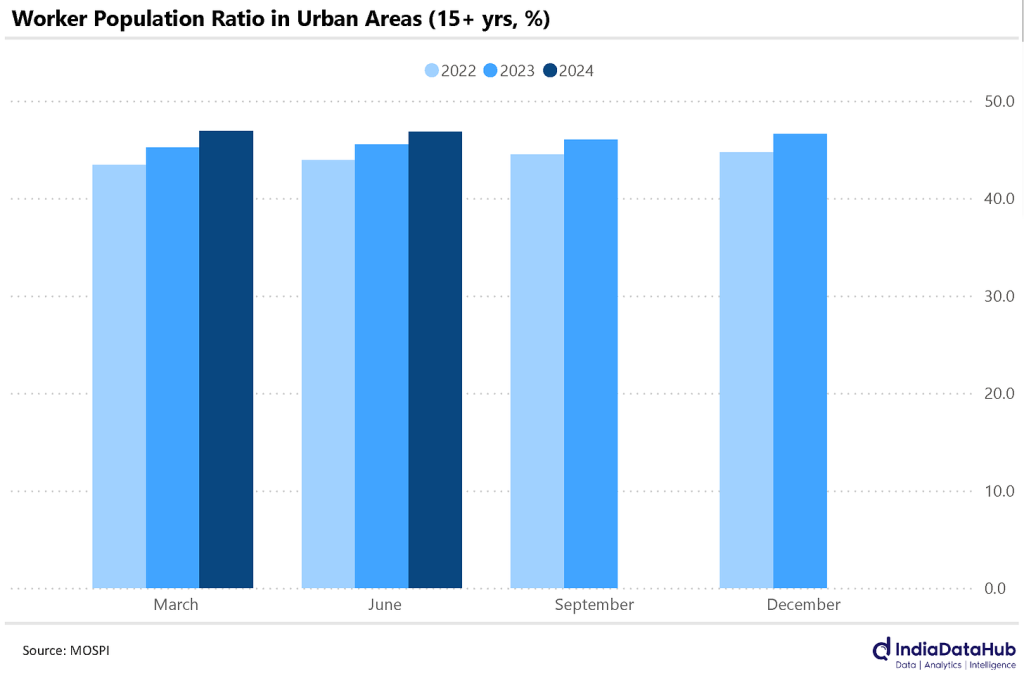

Well, things are looking up! Our ‘labour force participation rate’ — the proportion of working-age adults in our labour force — is increasing steadily. For over two quarters, it’s been over 50%. In other words, for half a year now, more than half of all working age people in India are actually trying to work. That might not seem like a big deal, but this magical 50% number has been really hard for us to reach. Similarly, our ‘worker population ratio’ (WPR) — the proportion of working age adults that actually have work — has been going up by ~1% a year. And despite all of this, our unemployment rate has stayed the same.

Think of it like this: if Virat Kohli made 50% of India’s runs in a match, but India was bowled out for a paltry 82 runs, Kohli made a decent but unexciting 41 runs. His innings was a small silver lining in a terrible match for India. But if India made 200 runs, and Kohli hit 50% of those, he probably played a beautiful innings to get to a magnificent century. The point is: percentages only tell you so much of the story. The overall size of the pie matters.

~94% of India’s labour force was employed last year, and ~94% of India’s labour force is employed this year. But crucially, India’s labour force has become bigger. To keep its unemployment rate exactly where it was, India had to create a lot of new jobs over the last year.

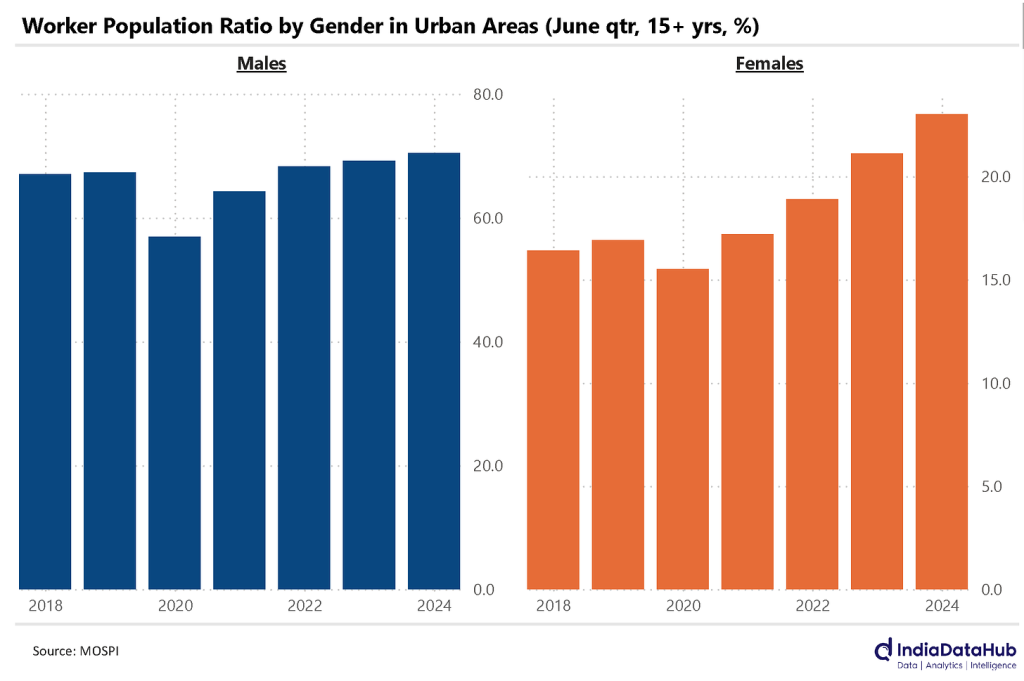

Perhaps the biggest challenge of India’s workforce is its terrible gender ratio. There’s always been a massive gap between the proportion of Indian men and women that work. In the June quarter, more than 70% of Indian men were working, compared to just 23% of Indian women.

Worrying as this trend is, thankfully, there’s been a slight improvement over the last couple of years. Something seems to have happened over the pandemic that has nudged a lot more women to work. June was the eight straight quarter when women’s labour force participation increased far quicker than that for men. Since June 2019, the WPR for men has gone up by 3%, while the WPR for women is up 6%.

There’s more white collar work

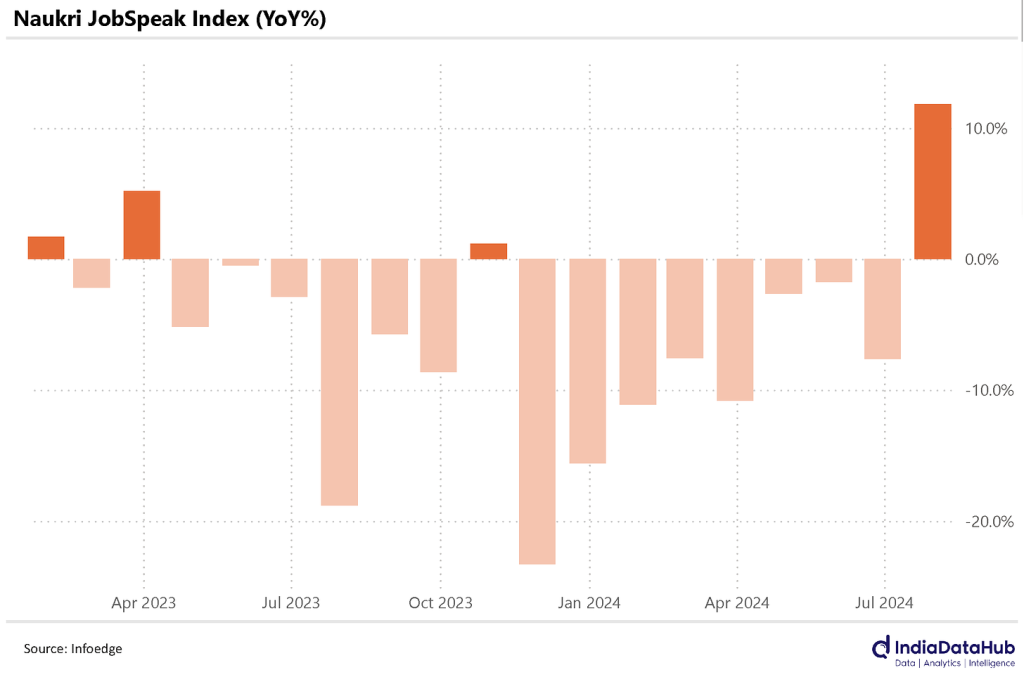

The job portal Naukri.com releases a ‘Naukri Jobspeak Index,’ tracking the number of postings on its website every month. Of course, not everyone posts jobs on Naukri.com — by and large, it’s only meant for white collar employers, and not all of them use it either. But while its absolute numbers might throw you off a little, directionally, it’s a good way to how things are going.

Last month, postings on the website grew by 11%. This is the first time they were up since late 2023. Once again, this signals a stronger urban labour market than we’ve seen in a while.

Rural job markets are weak

Everything we’ve discussed so far was for urban markets. In rural India, however, things are a little different.

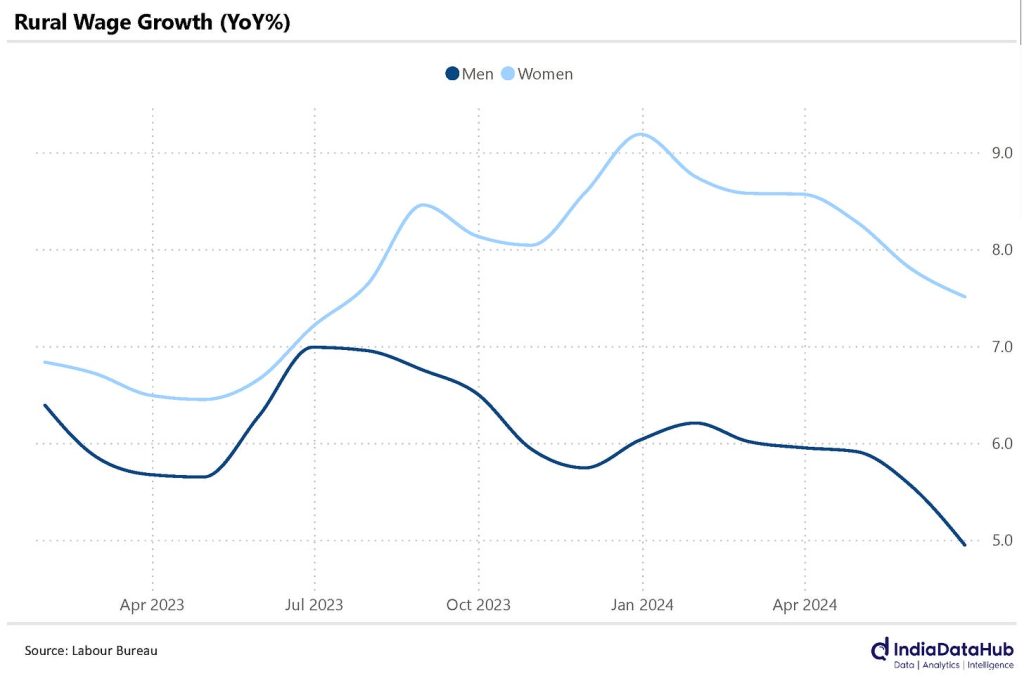

For one, wages are growing slower than they used to. In June, rural men saw their wages go up by just 5%, the slowest rate in two years. Rural women are slightly better off, having seen stronger wage growth in recent times. However they, too, saw the rise in their wages drop to a one-year low of 7.5%.

One big problem is a severe decline in the work provided under NREGA — which has been falling by a massive 30%, year-on-year, over the last couple of months. This has hit rural incomes badly.

At long last, inflation falls!

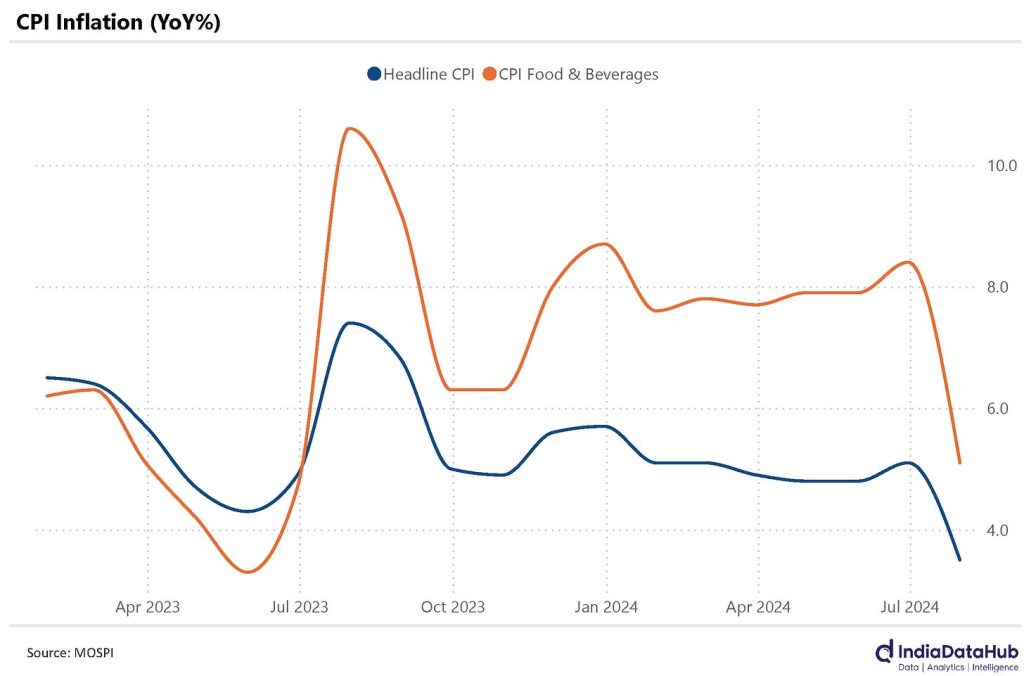

After a protracted battle against prices that simply refused to stop rising, inflation fell dramatically, and suddenly, in July: to 3.5% — below the 4% that the RBI targets — from 5.1% just a month ago. This is the lowest inflation reading we’ve had in a few years.

Don’t get too excited just yet, though. This dramatic fall owes itself, at least in part, to a ‘base effect’. It won’t stay for long.

See, there were vegetable shortages last July. Vegetable prices are always volatile, because they depend heavily on the weather. After intense heat-waves and a bad monsoon last year, vegetable prices — and tomato prices in particular — spiked last July. This year too, vegetable prices were slightly higher in July than in June, but the rise wasn’t nearly as severe.

To calculate inflation, you basically compare prices from a month with prices in the same month from the previous year. For July 2024’s inflation, you compare July 2024 prices with those in July 2023. Now, if July 2023 prices were unreasonably high, prices from July 2024 would look benign in comparison, and you’d get an inflation number that’s deceptively low. That’s the ‘base effect’: when the base number you compare something against is an anomaly, it distorts the whole comparison.

Let’s do this comparison again, but after ignoring all vegetable prices. There’s still a drop in inflation from June to July, but this time around, it’s a lot less dramatic: from 3.5% to 3.3%. Clearly, the inflation picture has improved, but the improvement is less pronounced than it appears.

So, how does the RBI see this all? Does less inflation indicate a cut in repo rates? Not so fast. The RBI has fixed its attention on challenges to India’s monetary stability. It wants our economy to grow, but not so fast that it creates problems. Inflation is only one such problem. But, as we wrote last week, there are other problems: specifically, the unchecked growth in credit — particularly personal loans — could create big problems for our economy if we aren’t careful.

It’s only if the economy slows down, or lending cools down, that there’ll be a serious case for rate cuts.

That’s all for this week, folks!