It’s the economy, stupid! Everyone wants your savings

We love IndiaDataHub’s weekly newsletter, ‘This Week in Data’, which neatly wraps up all major macro data stories for the week. We love it so much, in fact, that we’ve taken it upon ourselves to create a simple, digestible version of their newsletter for those of you that don’t like econ-speak. Think of us as a cover band, reproducing their ideas in our own style. Attribute all insights, here, to IndiaDataHub. All mistakes, of course, are our own.

A divide between companies and people?

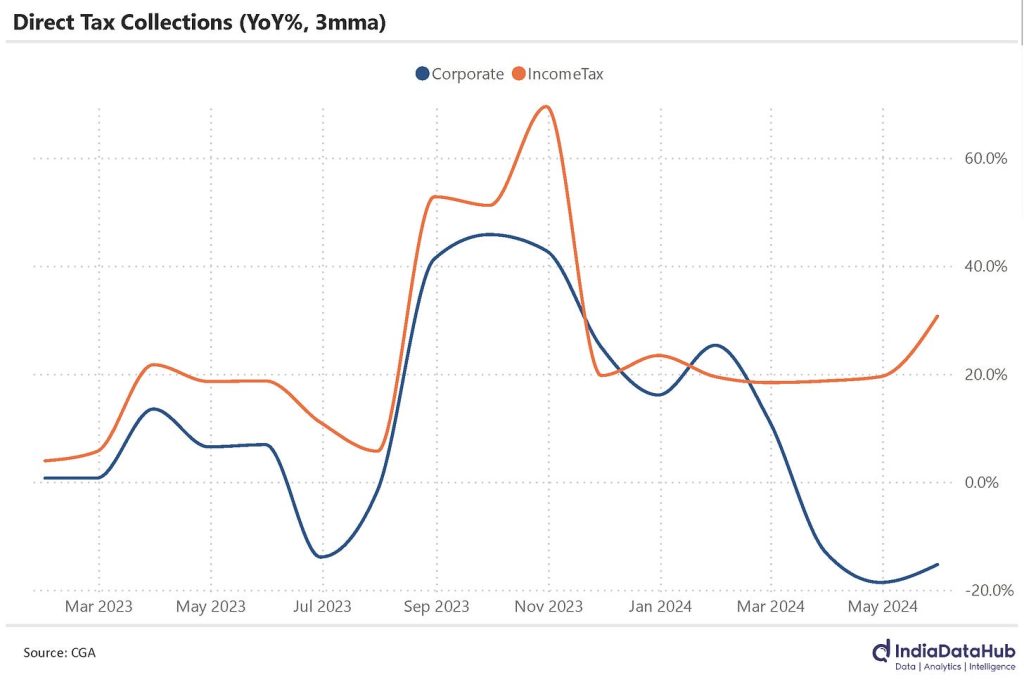

Corporate tax payments are falling.

We’ve spoken about this before. Corporate taxes were already falling for the three straight months between February and April. And the data for May suggests that they’ve fallen again. This time around, they’re only half of what companies paid in May last year.

Averaging the last three months, corporate tax collections were 15% below where they were last year.

But here’s the funny thing: while companies aren’t paying as much tax as before, individuals are paying a lot more!

The personal income tax people paid this May was almost twice what they’d paid last year. Averaging the last three months, personal income tax collections are 30% higher than they were last year.

Clearly, for whatever reason, the incomes of companies and people have split, and are rushing in opposite directions. A massive gap has opened up between the two. This is unusual. The last time it happened, the economy had been grinding to a halt, right before the COVID-19 pandemic. But right now, by all accounts, that isn’t the case either. What gives?

All we can do, I suppose, is wait and watch. Companies pay ‘advance tax’ in instalments, based on what they believe their income shall be. The first instalment of advance tax for this financial year was due early in June. That’s when many companies make their tax payments. One-ninth of a year’s corporate taxes are usually paid in June — more than April and May put together. So, June’s data is worth looking at closely. It’ll tell us a lot about the health of India’s companies, and by extension, of the economy.

Exceptionally small savings

Taxes can’t always sustain a government. When you’re running a country, you’re often doing things that take up more money than you currently have — which leaves you scouting constantly for cheap ways to source money. You can, of course, borrow money from the markets, at whatever rate they charge. But there are other ways of finding money.

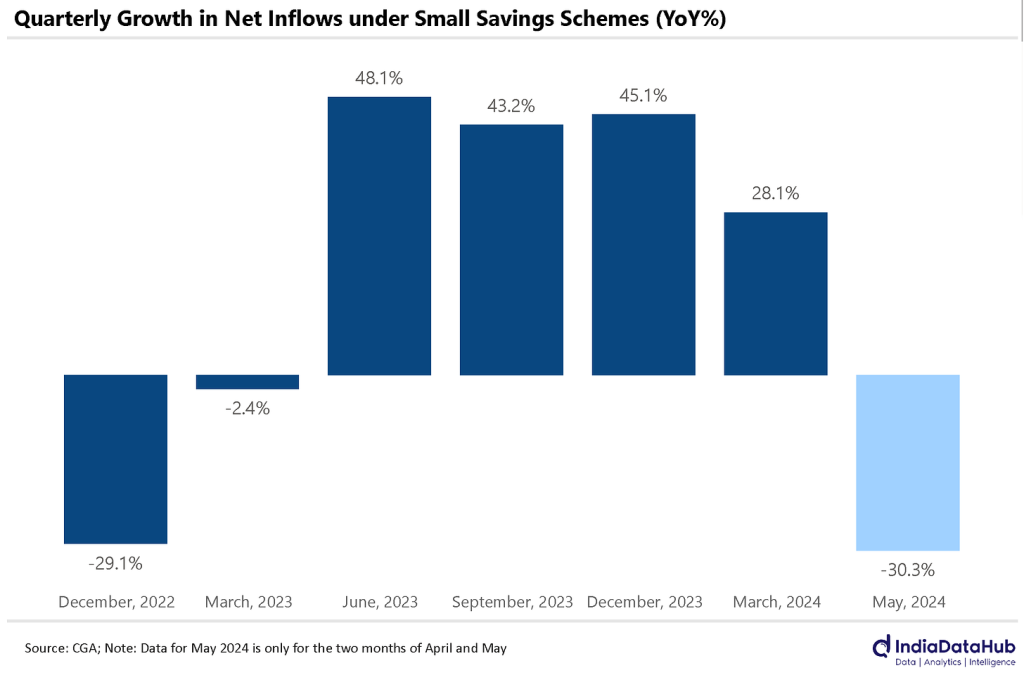

One of the cleverer tricks up the government’s sleeve is ‘small savings schemes’. These are central government schemes where retail investors can put in money for a steady, assured return. This kills two birds with one stone: it gives Indians a simple, safe place to keep their money, while creating a nice pool of money for the government to reach into. Both the central government and state governments often borrow from this pool to meet their deficits.

The problem, alas, is that people’s enthusiasm for these schemes seems to have taken a hit this financial year. In April, inflows into the scheme were 20% lower than last year. In May, they declined by 40%.

Let’s give you some perspective.

The total amount our governments, both at the Centre and in the states, borrowed from the markets last financial year was ₹18 lakh crore. The amount they’d collected from small savings schemes was ₹4.2 lakh crore. If these schemes didn’t exist, they’d have to borrow all this money — more than 20% of their borrowings — from the market as well. If inflows into these schemes continue to decline, you might see a lot more market borrowing, going ahead.

The savings war

It’s not just small savings schemes that are struggling for money, though. This is an industry-wide problem.

Think about it: a lot of finance runs on the money that regular people save. From companies in the stock market, to mutual funds, to banks, everyone wants your savings. Of course, there’s only so much to go around. So you’re probably putting your money wherever you get the best deal.

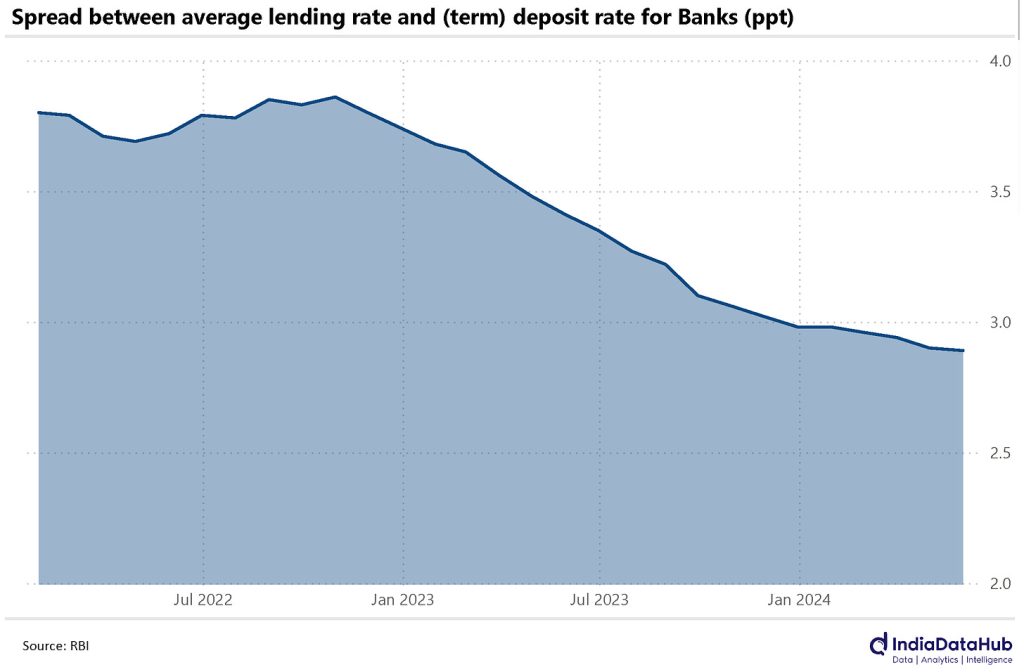

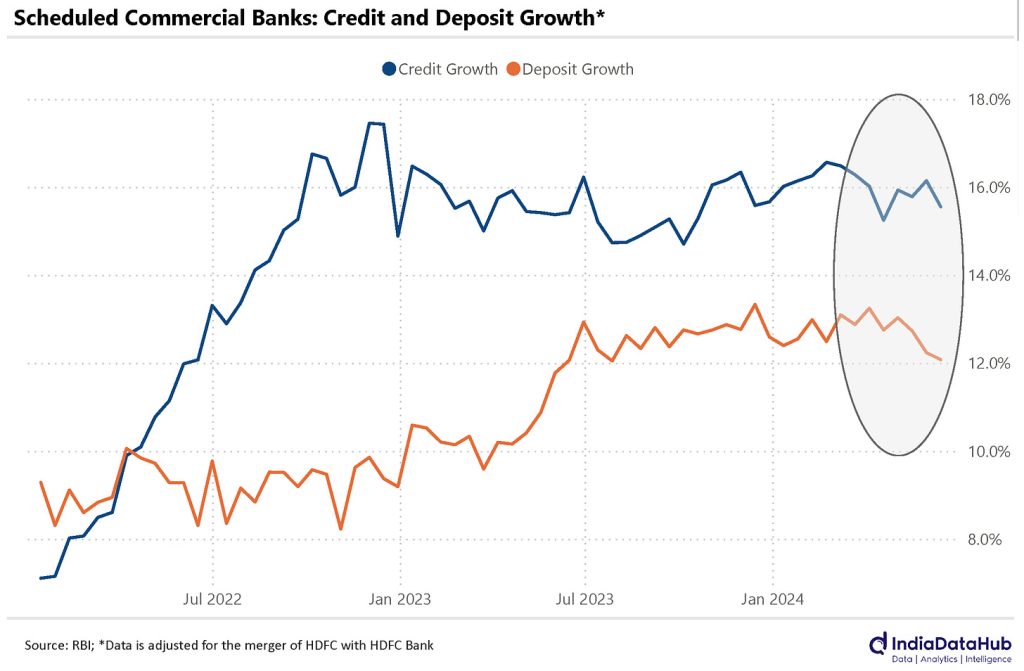

All this competition is starting to squeeze financial entities.

Take banks. They’ve steadily been offering better and better terms for deposits. Over April and May, at an average, banks have started offering more than 6.9% interest for fixed deposits — the highest since the RBI began tightening the supply of money in 2022. Meanwhile, they’re giving out loans at roughly the same rate as before, of 9.8%. What banks themselves make — the “spread” between the two — has come all the way down to 2.9%. That’s half a percent below where it was last year, and 0.1% lower than it was at the beginning of this year.

Even this isn’t helping, by the way. Banks’ lending has been growing faster than their deposits, and the ratio between the two — their ‘loan-deposit ratio’ — had grown in recent weeks. There’s little that banks can offer which is as attractive as the bull run that the capital markets are seeing.

Unless the RBI brings down interest rates and adds new money to the system, banks aren’t going to find it any easier to gather funds in the near future.

Surplus!

We’ve spoken before about how money comes into a country. Fundamentally, this happens in two ways. One, it comes in with strings attached — as it might for a loan or an investment, for instance. Two, it comes with no strings attached, when people have earned money from abroad in some manner — like by exporting goods or services.

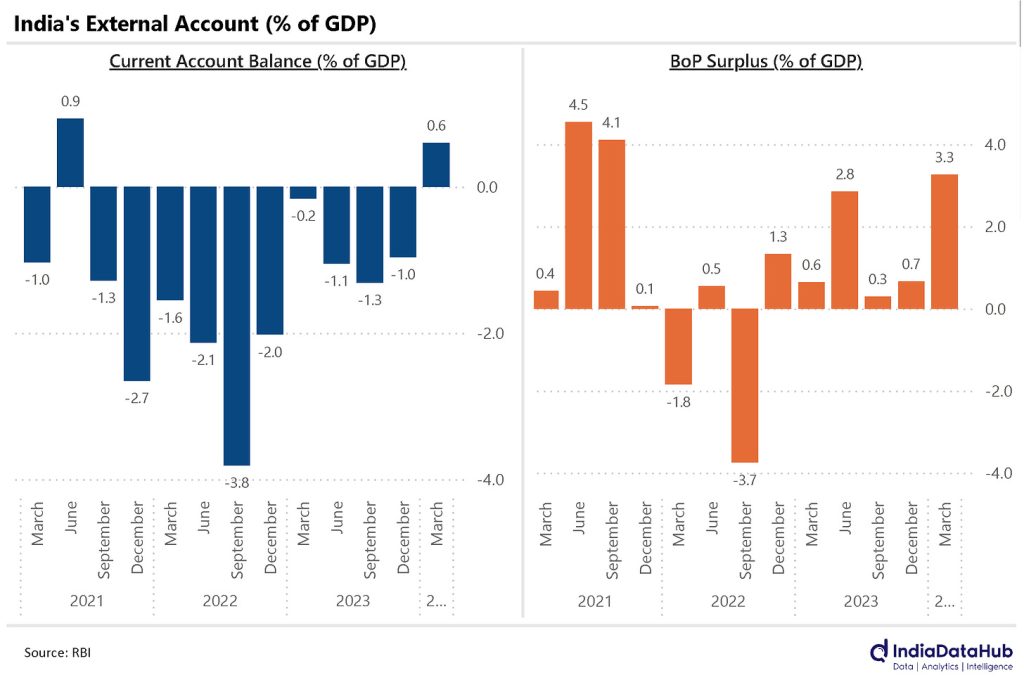

Formally, money that you bring in through the former is accounted for under the ‘capital account’, and the latter is accounted for under the ‘current account’.

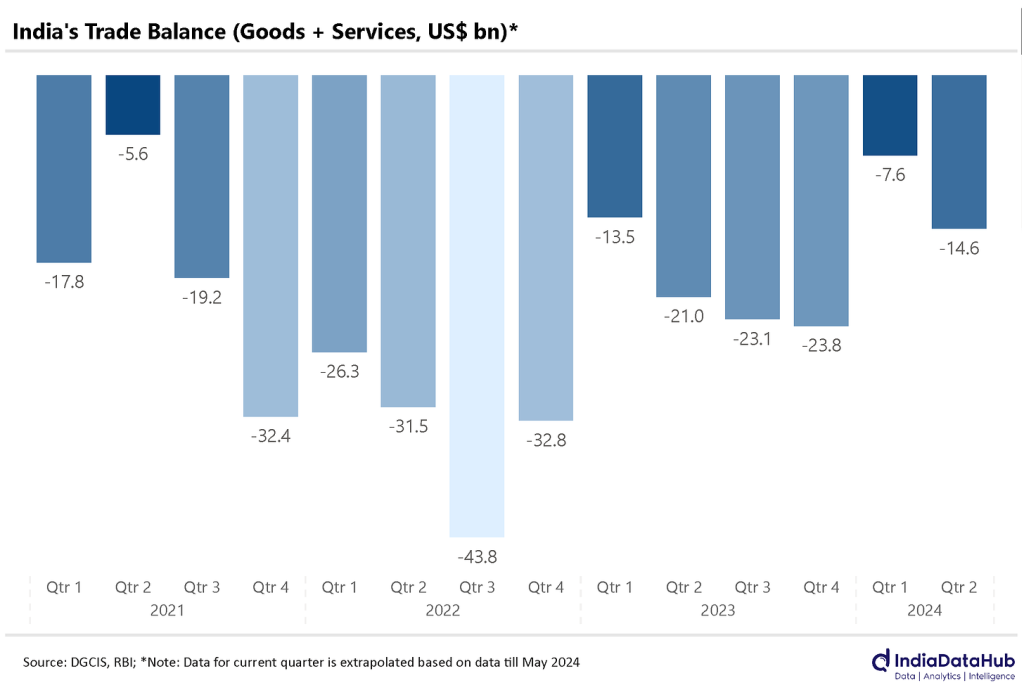

For the first time since 2007 (if you ignore the pandemic, when nothing worked quite like it should), India’s current account was in a surplus this March quarter. That is, India earned more money over the quarter than it spent abroad. Meanwhile, money kept coming into our capital account as well. All in all, more than 3% of India’s GDP for the quarter has come in from abroad. That’s one of the highest readings we’ve seen in years (again, if you ignore the pandemic).

This surplus came, in part, because our trade deficit went down sharply over the quarter. In contrast, our deficit for the June quarter was a little higher than last year. It looks like the surplus was a temporary blip. We’ll probably have a slight deficit once again for the quarter — of around 1%.

That’s all for the week, folks! Thanks for reading.