Can India Learn From Japan’s Population De-Growth?

An abandoned village is one where no one lives. Throughout history, people have abandoned their villages for various reasons—the threat of wild animals, flooding, dam-building, forest fires, wars, etc. Today, Japan probably has the highest number of abandoned villages.

The most frequently cited reason I found on the internet is Japan’s declining population. As older people pass on, their children become the legal heirs to their homes. The working-age legal heirs prefer cities and practically find no one to rent their village houses. So, the heirs simply abandon the property and leave.

These abandoned homes are called “Akiya,” and they are growing in number. The population degrowth has left almost 14% of all Japanese homes vacant.

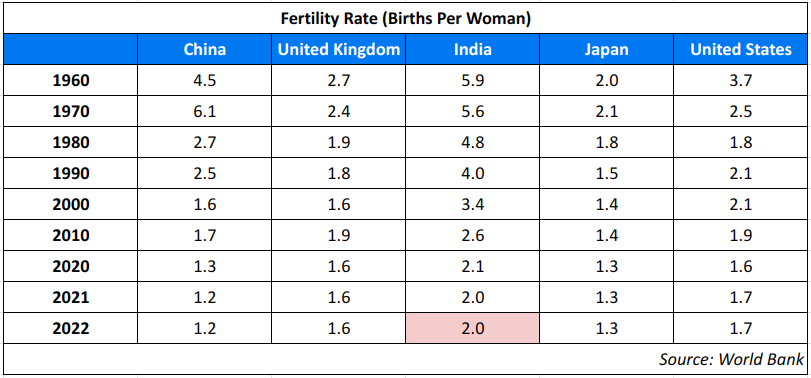

Japan’s fertility rate today is ~1.3 and declining. The fertility rate is the number of children a woman bears throughout her lifetime. A fertility rate of 2.1 suggests that the population is exactly replacing from one generation to the next. A higher rate means population growth, while a lower rate suggests a declining population.

Why the population de-growth?

- Birth rates boomed in most countries after World War 2. Children born around that time were called boomers. The boomers and the generations after them did not produce as many children. Economic progress and better education opportunities led to the youth focusing more on their careers and delaying marriages, which delayed having children. Many eastern nations faced this issue, so they resorted to liberal immigration policies to maintain economic growth. But Japan has, so far, resisted immigration and is, thus, feeling the pinch a bit more.

- Japan is still a patriarchal society where a woman is expected to shoulder all the household responsibilities, including raising kids. Highly educated women prefer to remain single or delay getting married lest they might have to give up their careers for marriage.

- Japan’s work culture, which could be credited for its prosperity, is also seen as a reason for its population crisis. Overworking is seen as a virtue. Most people work 12-14 hours a day. In most cases, people also stick with just one employer for their entire careers. The Japanese working class looks at these practices as a way of proving their loyalty to their employers. These practices also make it difficult for them to focus on personal life and relationships.

- The largest Japanese cities saw their cost of living ease slightly in 2023 but have otherwise consistently featured highly in the list of the world’s most expensive cities. Tokyo would usually be among the top five. General salary increases fell short of inflation levels. The Japanese youth often say they do not have enough money to get married, and the married ones do not feel financially secure to have a baby.

- Japan has the world’s highest life expectancy rate, at 87 for women and 81 for men. Over 92,000 Japanese are over 100 years old. The number of births in Japan annually is nearly half of the number of deaths.

Why does population de-growth hurt?

- As the proportion of the older population increases, the burden on the government’s social infrastructure, pension policies, and fiscal policies in general increases.

- The working-age population might have to pay higher taxes to fund the government’s social spending.

- The real estate and allied industries might see a demand slump. Japan’s abandoned houses are a case in point.

- The economy’s size could shrink. Exports or technological advancements might delay or reverse this process, but that may not always be the case.

- Businesses built to serve the younger population might lose relevance or see a shrinking market. There could be more demand for healthcare services and old-age homes than clubs, bowling ranges, or playschools.

The fallouts from Japan’s declining population have alarmed other economies that are facing a decreasing fertility rate. India has long experienced slower population growth, but its fertility rate has now fallen below 2.1.

A low fertility rate is more distressing than slow population growth. If an average woman today has two kids by the age of 30 instead of 25, the fertility is still the same, but conception is delayed. Despite achieving a replacement level, India’s population is expected to continue growing as the death rate is still lower than the birth rate, but we are expected to see a decline from 2050.

Is there a lesson for other countries?

This got me thinking. How are we, as a country, placed today to tackle population de-growth and an ageing population? Various data portals estimate India’s median age to be around 28 and 29. Today, the Indians in their 20s and 30s form the largest population cohort. India’s life expectancy has been gradually improving, and the birth rate is falling. This group might still be the largest cohort three or four decades later. So, India might have more older / retired people than younger / working-age people.

On average, this cohort might be better off financially than previous generations to support themselves. However, a smaller working class could impact the economy’s size and impact. We could learn from Japan’s issues. Are we setting the right foundation today to support growth despite a shrunken working class? Will the Indian economy continue to grow when our demographic dividend fades?

Japan and other countries with low fertility rates have been employing multiple approaches to solve for an aging population. India could borrow some ideas from their playbooks. India also has the advantage of learning from its shortcomings and developing a plan accordingly.

- Many western nations are filling the age gap in their population by encouraging immigration. That way, the foreign tax-paying workers in their countries support the retired population. India may not take this route because of the sheer size of its population.

- Some countries have proposed increasing the legal retirement age, which might increase the size of the working-class population. When France implemented a reform to increase retirement age from 62 to 64, it was met with nationwide protests. This is a politically sensitive matter that India will have to tread carefully.

- Countries are encouraging the young population to have more children by offering monetary and policy support for bearing and raising children. In 2023, Japan earmarked $25 billion for childcare funding over the next three years. Japan has also introduced maternity and paternity leaves that last for a few weeks and childcare leave for up to a year.

- Encouraging female workforce participation has helped Japan partially delay the effects of an aging population for several years now. Culture plays a big role here. Married women or mothers are often discouraged from working. Even those who work often face workplace hostility, discrimination, etc. A gradual shift to make workplaces more enabling for women is imperative.

- Technological advances could help boost workforce productivity and offset any possible decline in output due to a smaller workforce. The use of drones, robots, and AI could help cover workforce shortages.

All the aforementioned pointers come at a cost to the government. It will also have to spend on more healthcare centers, wellness centers, old age homes, etc. The sheer size of our population makes it difficult for the government to increase per-capita spending materially. These expenditures will rise in the wake of smaller tax collections from a shrinking pool of working-age population.

A declining population is not really an issue if there is a balance between working and non-working people. If Japan continues on its current path, its population might halve by 2100. However, if it manages to achieve a replacement level of fertility rate, it can continue to sustain itself comfortably after that.

Similarly, India could manage itself well at a population level of 1.5 billion people or even at 1 billion people if the working population can support the older population while also maintaining a replacement rate of fertility.