It’s not even wrong

A downside of writing about finance is that you are cursed to see the same dumb things and write about them over and over again. It’s a bit like being Sisyphus, if he were a writer.

Uhmm, excuse me, who is sissy-puss?

So, according to Greek mythology, Sisyphus was a guy that pissed Zeus off. As his punishment, for the rest of time, he had to keep rolling a boulder up a hill, only for it to roll back all the way down again. His name is literally a synonym for “doing something pointless again and again.”

Well, that’s exactly what I’ve been up to.

Last week, I published a post with some historical context on the current bear market, and shared some tips on what to do (and more importantly, what not to do). We also recorded a video based on the post.

Between the video and our social media posts, we got a ton of comments. While we’d like to tell you that every single comment you write is extremely special to us, some of you hurled absolute garbage at us. Reading comments on social media is always a bit like taking deep breaths by an overflowing drain — and this was no exception.

Much to my non-suprise, there were some spectacularly dumb takes in the comments. I’m not usually a jealous person, but I was jealous of the sheer confidence with which people said things that were not even wrong. Nobody should be blessed with this much unearned confidence. There’s never a shortage of dumb investing takes, but it feels like when there’s a bear market, even the residual common sense left gets thrown out of the window.

And so, I must write. It’s a compulsion. Pretty much everything I’ve ever written about investing was because I got bothered by some dumb take on the internet. When I’m bothered, I write to bother even more people — a brotherhood for the bothered. This post is no different.

I’m going to highlight some of the scientifically stupid takes I came across. I’ve addressed most of them in the previous post, but I don’t care. I’ll say the same damn things again.

Yo, Zeus. I’m rolling the boulder up once more.

Sell EVERYTHING!!!

The most common comment was some version of “things are bad, it’s all ending, sell everything!”

These gloomy takes are a symptom of the most virulent pathology that afflicts individual investors — one that even MRNA vaccines can’t help with — macro tourism. The effects are severe. This disease causes strong hallucinations, delusions, and flights of fancy among investors, leading them to a ridiculous degree of faith in their non-existent market analysis capabilities.

Infected investors see vivid fever dreams about everything that can go wrong in the world. Like how the fart of a Taliban war-lord in Afghanistan can cause a tsunami in the Indian ocean, which disrupts global shipping, causing an oil price shock, leading to a recession in India, causing a stock market crash.

Today, Trump looms large in the minds of these poor macro tourists. Trump is the ultimate boogeyman, a one-person embodiment of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse; the fount of all fears. According to investors with stage IV macro tourism syndrome, Trump will be the end of everything. The fallout from his actions will make the Great Depression look like a cute little anime episode.

Maybe he is. Let’s assume, for a second, that there’s a high probability of everything crashing and burning because of Trump. You have two options:

Option 1: Sell everything and wait for things to get better

You need to get two things right here — your entry and exit. But be honest with yourself. If you’re panicking right now, you’ve probably already messed your entry up. Are you really so good at market timing that you’re sure you’ll get your exit right? If you do, well, you shouldn’t be reading this blog. Go shitpost on Twitter about how Warren Buffett is an old geezer who got lucky in life, like the rest of your enlightened lot.

Option 2: Trade the disruption

If you are so certain that bad things will happen, why sell everything? Even Trump can’t end money altogether — at some point all the money that’s leaving the markets will be invested somewhere. Shouldn’t you be buying things that will go up because of Trump’s madness? Shouldn’t you be trading the volatility? (Of course, given that Trump changes his mind more often than a chameleon changes colors while sitting on a disco ball, do you really think you can handle it?)

If you can do neither, why worry about all this macro nonsense? You might as well spend your time watching The Fabulous Lives of Bollywood Wives. Or maybe this amazing Macdonald joke.

Trump is just a placeholder. Replace Trump with any other crisis; the macro tourism script remains the same. In the last 4-5 years, we’ve cycled through “the pandemic will kill us all”, “Russia-induced WWIII will kill us all”, “China’s collapse will trigger the great depression”, “US debt default will trigger the great depression”, and “Israel-induced WWIII will kill us all”. Much to my profound disappointment, I ain’t dead yet!

Macro tourism is easy. If you can just worry about world-scale events deeply enough, you can save yourself the effort of thinking through the complicated nature of markets, and grappling with questions that have no easy answers. Sadly, it’s a shit way to make money.

It’s always risky, bro!

The second silly thing I saw was a series of comments that vomited out a list of reasons for why people shouldn’t invest now. On the dumbness spectrum, this falls close to the dumbest end — maybe just one notch above “sell everything”.

I wrote about this in the previous post, but I’ll say it again: the reason an equity risk premium exists is because equity is risky! No risk, no premium!

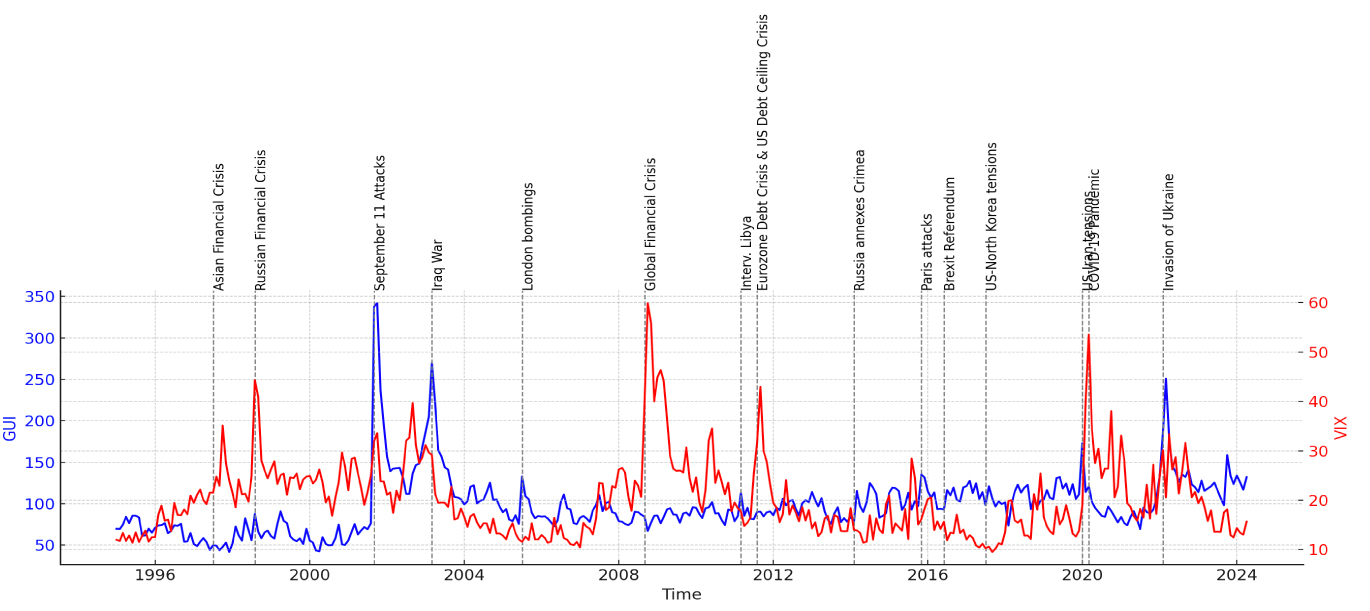

Guess what, the world is always risky. Excrement keeps hitting the proverbial fan at regular intervals so often that the fan is crusted over in excrement. Don’t believe me? Well, we have different indices to measure geopolitical uncertainty, trade uncertainty and policy uncertainty.

Here’s a chart of the World Uncertainty Index:

World Uncertainty Index:

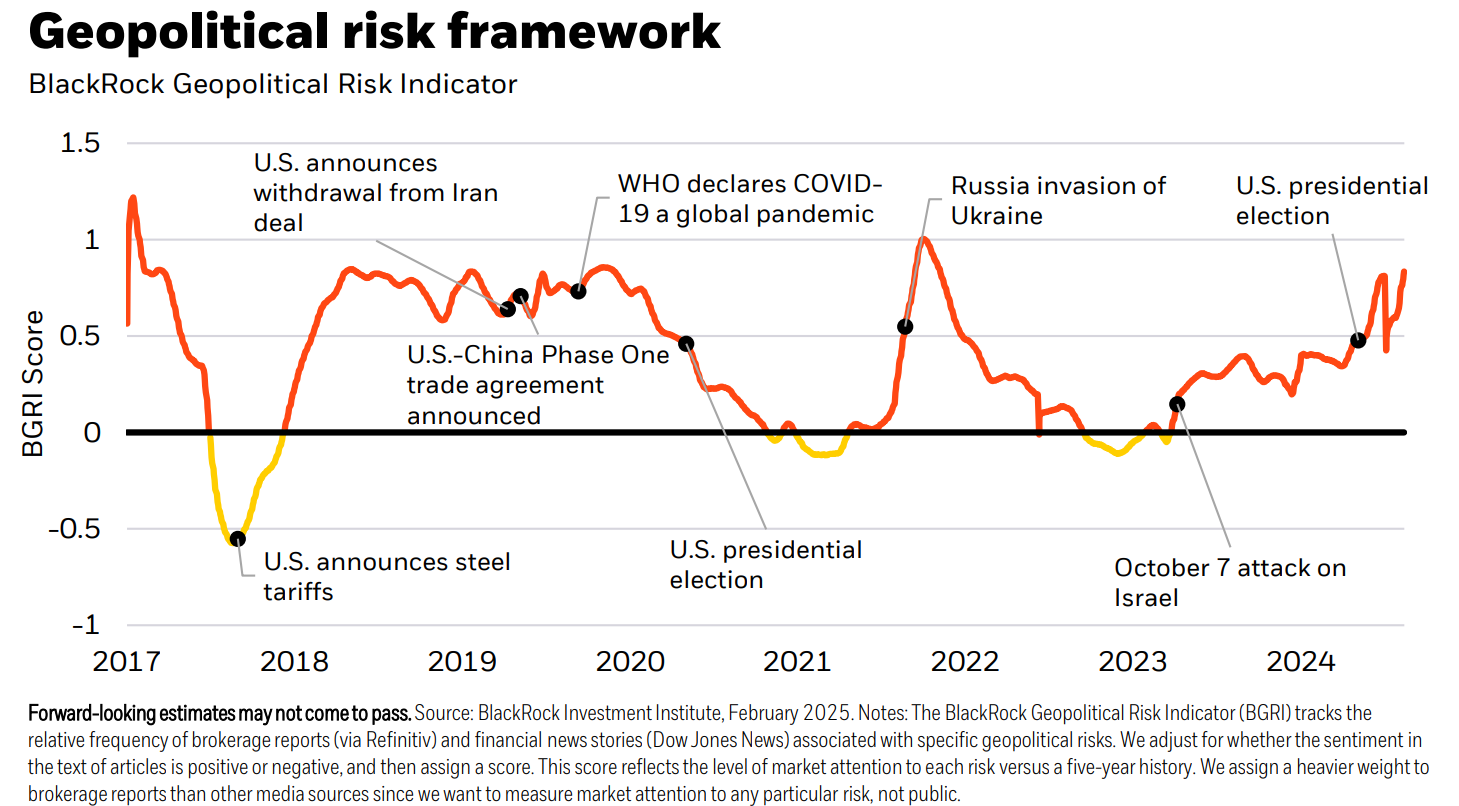

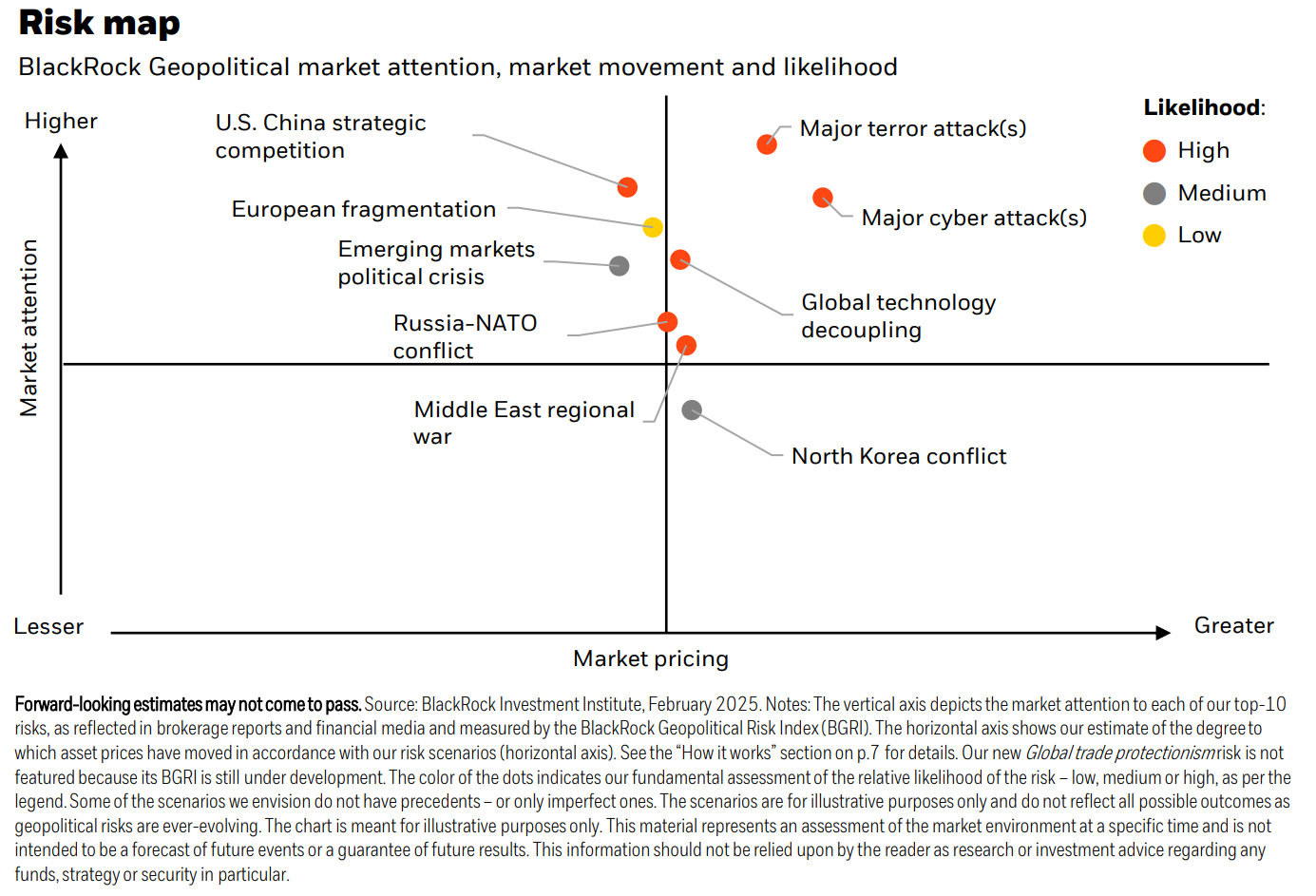

BlackRock quantifies geopolitical risk:

BlackRock

BlackRock

What do you notice?

Look, things might be bad right now, but bad things happen all the time. Markets digest the bad stuff and go about their business. Many investors, though, have a hard time digesting the fact that it’s quite normal for the world to spin off the rails every once in a while. If you are waiting for when everything is sunshine and roses before you invest, I’m afraid you’ll always be poor. And the tragedy is, your poverty doesn’t make the uncertainty go away — it only enhances it. #Sad

What’s the less-dumb thing to do, then? You need to understand how geopolitical risk actually affects the markets.

Geopolitical risks flow through many channels. The evidence tells us that geopolitical uncertainty can affect investments by companies, reduce employment, reduce trade, lower economic growth and increase market volatility… for a while. But that doesn’t last forever. Over the long run, that economic and market volatility usually subsides. Companies adjust to their new reality, and their business kicks into high gear once again — and ultimately, it’s their earnings that you’re buying into. In fact, the vast majority of geopolitical events don’t even matter for long-term investors. They’re just distractions.

Think of it this way. Equities are risky; they’re volatile and can fall a lot. Not everybody can hold on to them. So, those that do have the grit to hold on will demand a premium to compensate for all the fear and heart-burn they face, instead of simply going for a risk-free asset like a government bond. This is why equities tend to beat risk-free assets over the long term.

The bottom line is: no pain, no premium.

Petty paranoia

The stupidity doesn’t end here.

Macro tourism and risk-aversion have an unholy love-child: paranoia about imaginary scenarios. When something bad happens, novice investors keep extrapolating linearly — as though things will keep moving in one horrible direction forever — until they end up at utterly illogical conclusions.

If the Indian economy hits a rough patch, the illogical conclusion people rush to is that we’re turning into Chad or Somalia. If Nifty is down 15%, the illogical conclusion is that we’re only 85% away from zero. If three people sneeze in Chennai, the illogical conclusion is that we’ve hit the next global pandemic — ChOVID-19 — and we’re all going to die!

That, however, is just the first stage of this ailment. Then comes the second stage of petty paranoia syndrome, where people search for things to confirm their paranoia. This is easy; the human brain is hardwired to overweight negative news. It’s not hard to find doomporn to confirm your preexisting notions either. One look at CNBC is all it takes.

We tend to catastrophise. We treat the worst possible outcome as plausible — maybe even the only valid truth — even when it’s clearly not.

Try this: ask a bearish investor for three reasons the market will fall. They’ll give you 30. That’s because they start with the assumption that things are bad, and then hunt for information that confirms this bias. And of course they’ll find them. There’s never a shortage of things to be worried about. Billions of things happen in the world on any given day, and statistically, a few hundred million of them will be bad.

If you can’t get over your inability to stop worrying about the worst, you’re better off investing in fixed deposits and gold. That’ll free up the mental space for you to worry about your future poverty.

Macro is about understanding the world

I’m not saying “macro is useless”.

All I’m saying is this: if you think you can make money by reading hysterical headlines or random reports and listening to frothing loudmouths on TV, I hate to break it to you, but you’re going to lose your money, and you’ll soon end up sleeping under a flyover. And the last I checked, the underside of a flyover is no Ritz Carlton.

Look, macro matters. But for every bit of insight it gives you, it also leaves you with enough nightmares to keep your bed moist for a month. One of the best articulations I’ve heard of this is by Cullen Roche, one of the most thoughtful finance writers I know:

So, to me, so much of this is about behavior. I think a lot of people study macro, and they think they’re going to become the next George Soros or Ray Dalio, and they’re going to use these ideas and beat the market and have some sort of high-fee type of hedge fund-type of allocation where they’re able to generate tons of alpha and that sort of narrative. Whereas I take it from the opposite view that to me, macro is really about understanding the world for what it is so that as we navigate it, and we encounter all of the behavioral difficulties that are inevitable across the investing environments that we’re trying to navigate, that we behave better, in essence, because we feel more comfortable because we understand a lot of these big-picture things that a lot of which are just incredibly, incredibly confusing.

A lot of it is hysteria that is based on either trying to drive eyeballs, or in a lot of cases, it’s based on just bunk, a lot of misunderstandings about things and the causality of them and the potential outcomes. And so, to me, so much of macro is just about understanding the stuff for what it is so that as we try to navigate the day-to-day trials and tribulations of the financial markets, that we’re not tripped up and prone to all of these behavioral biases that can result in really catastrophic mistakes for people at times.

I love this framing.

When you’re informed about the world, you aren’t quite as surprised by random events, which reduces the odds that you’ll make rookie mistakes. But that’s it. It’s not a good way to trade and make money. In fact, of all the different approaches of making money, macro has to be the hardest. If you just put a 200-day moving average [1, 2, 3], buy above and sell below, you’ll end up doing better than anyone that’s trading on macro bullshit.

I stress on this because hey, I get it. I know the allure of macro. I listen to macros guys regularly. But there isn’t one episode that goes by where I don’t come off with the feeling that the end of the world is imminent, and that I need to sell everything and buy gold. Listening to the macro masturbators, distant possibilities seem like urgent worries. WW-III? 10 mins away. Nuclear Armageddon? 5 mins away. Another terrible Salman Khan movie? 1 day away!

When it comes to investing, it’s important to know what you can do — but knowing what you can’t is even more important. As the old Charlie Munger quote goes, avoiding stupidity is easier than seeking brilliance.

The stock market is NOT the economy!

There’s another common comment I saw: the Indian economy is bad and that’s why the markets are falling. Sounds intuitive right? If the economy does well, companies do well, and the market as a whole does well. If the economy is in bad shape, then the stock market will naturally do poorly too.

However, like many pretty-sounding stories, it’s wrong.

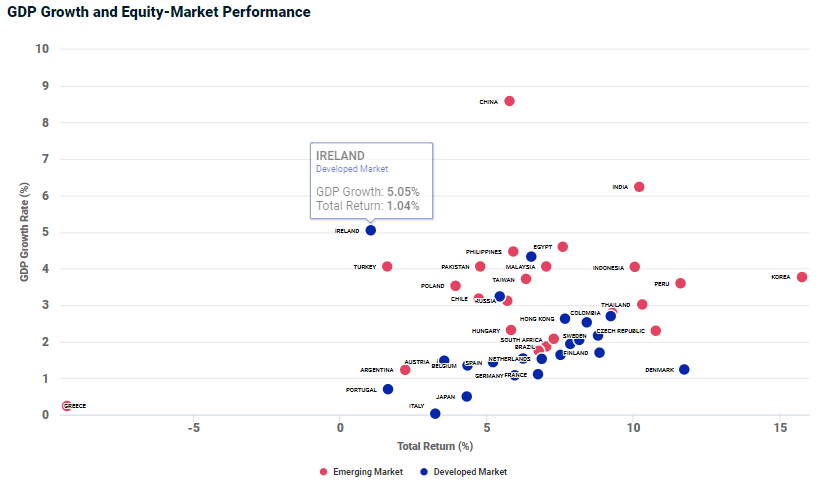

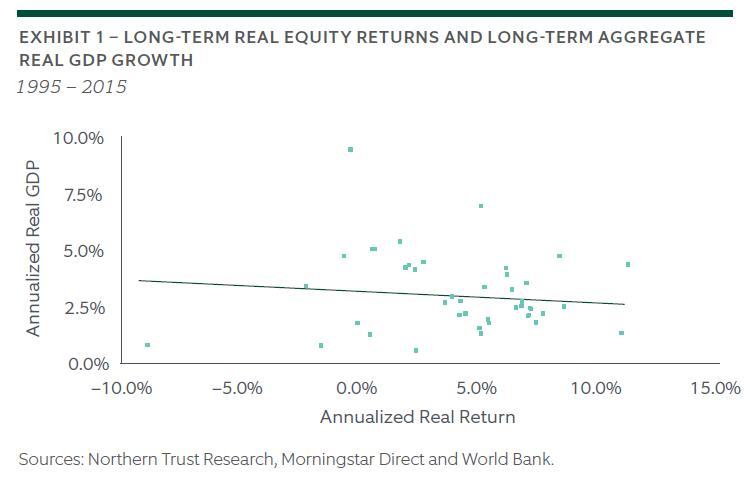

There’s enough evidence to show that there’s no relationship between a country’s economic growth and market performance. Consider this: even if you had perfect foresight and knew about a country’s GDP growth rate for each of the next twenty quarters, there’s no guarantee that you’d make money. In fact, you’ll probably get all your bets upside-down. Because here’s something even more counterintuitive: countries with high growth often have lower stock returns than countries with lower growth rates:

In the developed markets group, the high-growth countries returned 12.0 percent in the following year, while the low-growth countries returned 13.1 percent, although they did so with higher volatility (21.2 percent versus 19.1 percent). In the emerging markets group, high-growth countries provided both higher returns (12.9 percent versus 12.6 percent) while exhibiting lower volatility (34.9 percent versus 38.9 percent).

Dimensional’s researchers then asked what would happen if economists had perfect foresight, which simply doesn’t exist in the real world. With perfect foresight, one could buy the stocks of countries with high economic growth rates and avoid (or short) the countries with low economic growth rates. Dimensional found that the low-growth countries in the developed markets group returned 13.2 percent versus 11.2 percent for the high-growth countries. However, it did find that in the emerging markets group, the opposite was true.

Why? It’s all about expectations:

- Countries with higher growth rates attract more capital. This pushes up returns and valuations, which lowers future expected returns.

- Markets are forward looking. They’re pretty good at pricing the future expected growth rates. So, next year’s good or bad GDP prints are more or less already baked into stock prices. Unless there are unexpected surprises, stock prices don’t tend to move much. The same applies to most other economic datapoints.

- A country can grow without the benefits accruing to owners of capital. That growth may instead show up in the form of higher wage growth.

MSCI

Why this disconnect? First, increased globalization means that domestic stock markets may be more exposed to global growth drivers than domestic ones. It’s also possible that stock markets had already priced in expectations about future economic growth. Finally, supportive monetary policies around the global have driven capital flows into riskier assets like equities, potentially severing the link between the real economy (proxied by GDP growth) and stock market performance and valuations. — MSCI

I know, I know. One of you will now smugly point out that Indian equity returns and nominal GDP returns are broadly the same. Check-and-mate! You’ve schooled me on my Western bias! But if you’re one of these smug people, ask yourself this: do you really want to bet your life’s savings on a single data point from a statistical outlier?

Keep your politics in your pants

Many comments ascribed political reasons to the stock market. The current market fall was all the doing of XYZ leader or ABC party. <Insert your pet issue> zindabaad!

As investing mistakes go, mixing politics with investment choices isn’t just a rookie mistake, it’s also unoriginal. Make unique mistakes if you have to. What’s the point of making mistakes that have already been made? Not only do you burn your money that way, you also broadcast how bland your personality is.

There are numerous things that move stock prices in the short run. Politics is one of them. Jumping to conclusions on why the market will go up or down based on one among a thousand factors is plain silly. To do that, you need to patiently eliminate the effects of every single other factor. And let’s face it, none of us are smart enough.

And then there’s this other thing: politics is to the mind what lemon juice is to the eyes.

Look, you should be politically informed, for two reasons:

- It’s important to be an informed citizen for the health of our democracy blah blah.

- More knowledge helps you become a more nuanced political shitposter on twitter. If you’re looking for all that sweet, sweet engagement, you can’t have stale shit-takes.

Investing isn’t one of them.

On a serious note, investors overestimate how much politics impacts the markets. Zoom out and think about the long term history of the Indian market. From 1980, the BSE Sensex has delivered returns of about 15-16% CAGR. Over this span, India had 11 prime ministers across four parties.

Do you seriously think that that one politician or party you hate can buck this trend? Do you really think they’re impactful enough to turn India into Zimbabwe or Chad in just 5 years’ time? While there have been brief ups and downs, by and large, the Indian economy and markets have chugged along steadily for the last four-and-a-half decades, regardless of who is in power. It would take serious skill to reverse that trend.

As Ben Carlson rightly points out, the ability of politicians to move markets is vastly overstated. Don’t believe the news — there’s only so much they can do. It’s not that policies don’t matter at all, but policies usually take time to implement. They play out on the scale of years. To base financial decisions on short-term political noise is investing suicide.

For better or worse, politics is an emotionally charged subject for many people. That’s understandable. But their likes and dislikes for a party then colours their perceptions about the markets, the economy and the investment decisions they should make. That’s where they go wrong. Letting emotions guide your investments is a time-tested strategy to attain generational poverty. Works 100% of the time.

A little knowledge is a dangerous thing

Going through all those comments, and listening to the “experts” explain the bear market, reminded me of a few classic quotes:

“An empty vessel makes the loudest sound, so they that have the least wit are the greatest babblers.” ― Plato

“The problem with the world is that the intelligent people are full of doubts, while the stupid ones are full of confidence.” ― Charles Bukowski

“Light travels faster than sound. This is why some people appear bright until you hear them speak.” — No idea who said this

You know there’s an issue when you can’t distinguish the sounds coming from someone’s mouth from those coming out of their behinds. I mean, if you used the bullshit people manufacture as manure, you’d end up with a dead garden.

This line by the brilliant Iain McGilchrist stuck with me:

“Not ignorance, but ignorance of ignorance, is the death of knowledge.”

People are prone to bull-shitting. In most cases, it’s harmless. In the markets, sadly, it’s not. The problem, today, is that anyone can post exaggerated nonsense on social media and gain a following. None of it has to be true — if it can bait people into a reaction, it’ll get ‘engagement’. If people said the stuff you see on “popular” twitter accounts out aloud in real life, they’d have 2-3 teeth left.

There are two people that I follow on Twitter that can charitably be described as… interesting characters. One apparently once bought some stock that went down a lot during the dot-com bubble, and has coasted on that ‘success’ for over two decades. Now, he psycho-analyses market movements like he’s super-Freud. The other is a social media critter that has been predicting Nifty’s fall to 8000 for about a decade.

Both have more followers on social media than many famous movie stars.

Kill me.

Two factors make everything worse. One, money is an emotional object that rouses the worst emotions in us. Moreover, we’re not rational creatures, but rationalising ones. Knowingly or unknowingly, we self-select for people that say what we want to hear.

There are few things dumber than leaving your brain behind and investing based on what some Tom, Dick and Harry said. Two things come to mind:

- A few weeks ago, all the 10 people on Indian finance Twitter soiled their underpants because Sankaran Naren, the veteran fund manager at ICICI Prudential Mutual fund, said that investors should stop their SIPs in midcap and smallcap funds.

- A colleague said he had sold his equities because some other famous investor was bearish.

Look, you can’t outsource your conviction in investing. It terrifies me how easy it is to dupe people into throwing their hard-earned money by pretending that they’re directly getting buy and sell calls from ‘famous’ investors. It’s important to listen to knowledgeable people and learn from them. But outsourcing your thinking, judgement, common sense and conviction to some mouth-breathing idiot, regardless of their supposed “expertise,” is ridiculous.

It’s tragic; people spend more time choosing the colour, print and fabric quality of their underwear than they do in analysing their investments. What an upside-down world we live in!

What is Japan?

No investing post or video is complete without a “what about Japaaan?” comment. And sure enough, I saw those this time as well. For people who write about finance, like me, there are few things that can unravel your psyche with such precision.

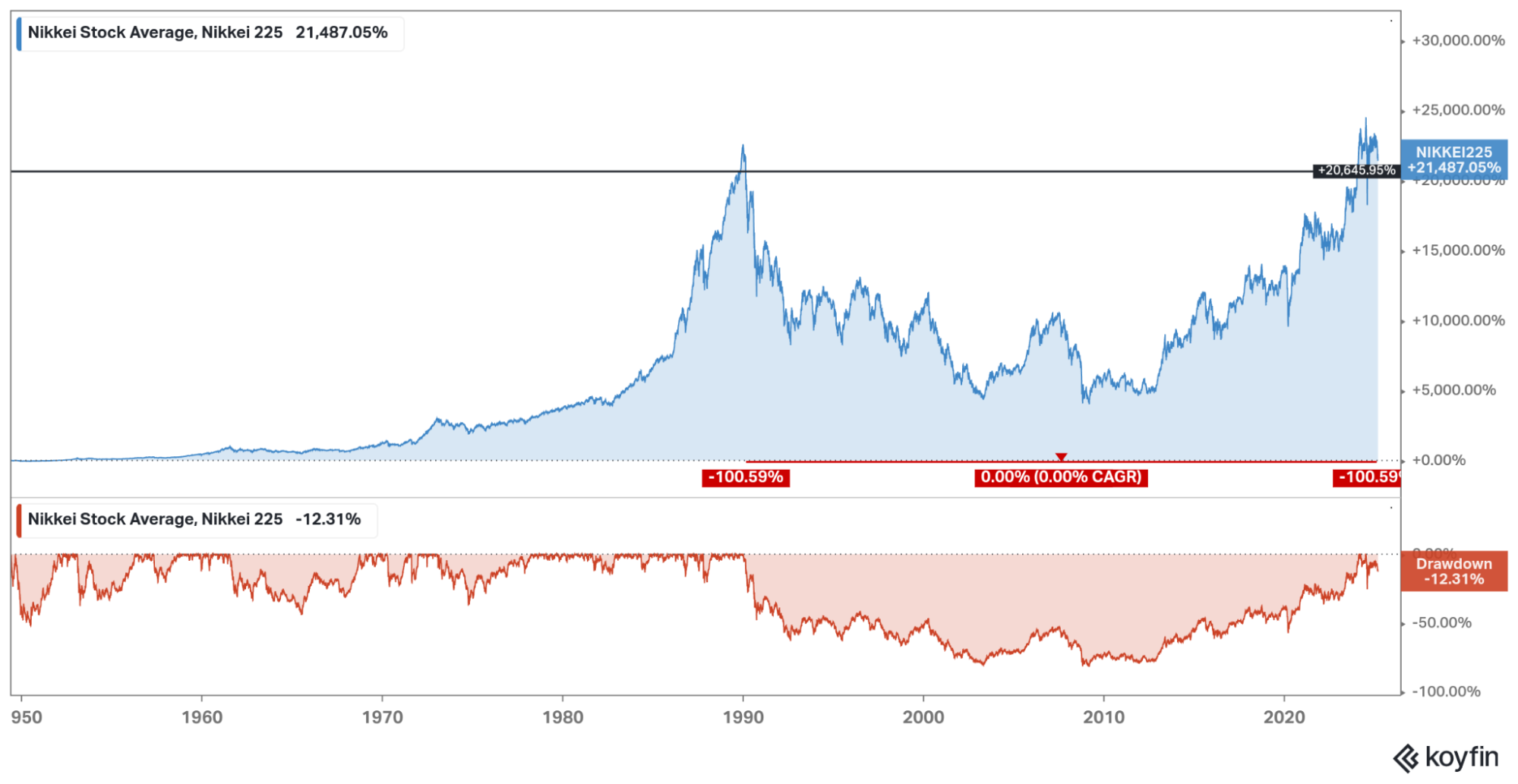

Now, the odds are that you’re young and have no idea what the comment means. Let me explain. In the late 1980s, Japan saw one of the greatest asset bubbles ever, which then burst spectacularly. It took over 35 years for the Nikkei index to reclaim its 1980s peak. And ever since then, it’s become everyone’s go-to example for when the market didn’t recover in the long term.

Nikkei drawdown

So whenever you write a post asking people to think long term, one annoying prick always comments “what if India becomes Japan?” Grr.

Hey, you, annoying prick. Screw you. Let me ask you some hypotheticals.

What if lead from your pipes is leaching into the water you drink? Stop drinking water.

What if the food you eat is laced with cyanide? Cease eating at once!

What if, as soon as you step outside your house, you slip on the stairs, fall down, crack your skull open and die? Never leave your house.

Shall I keep going?

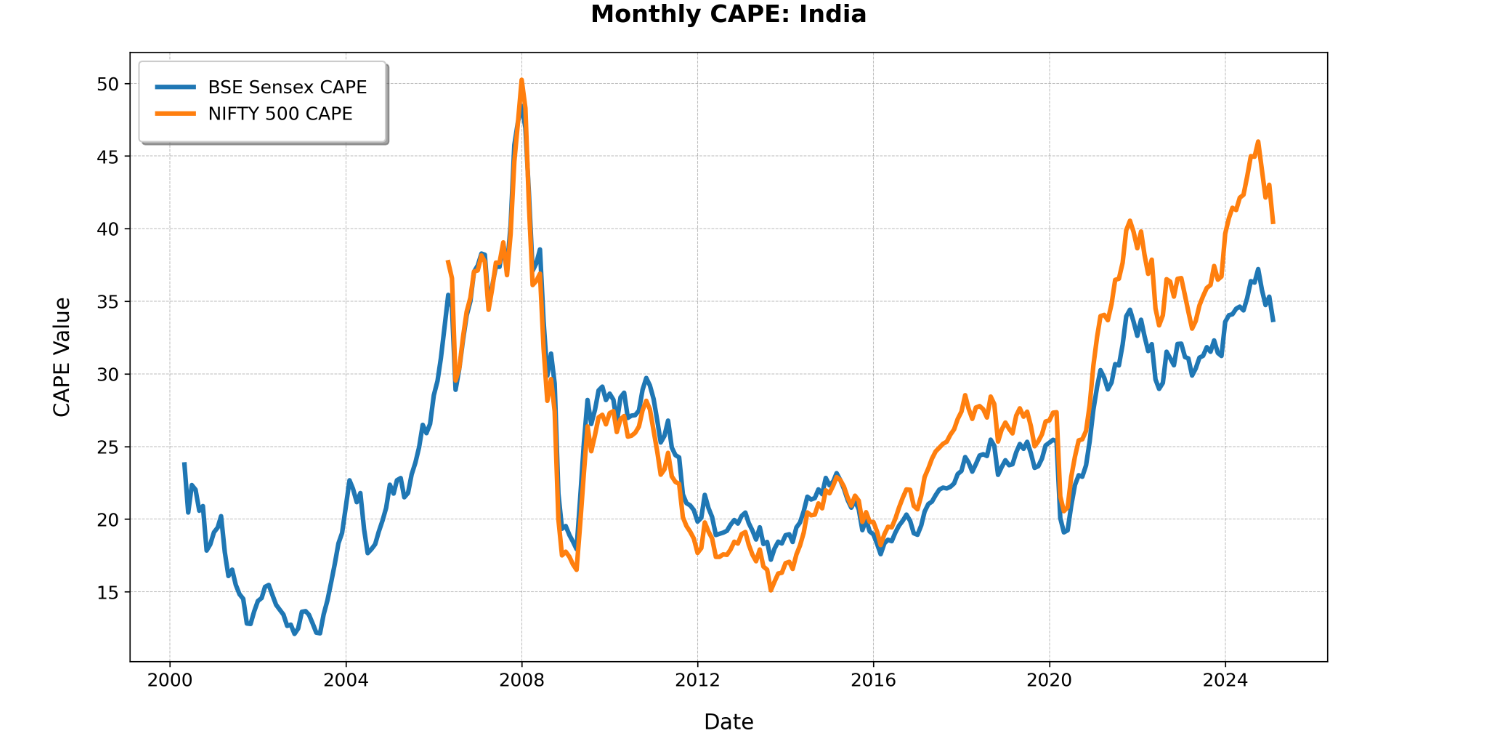

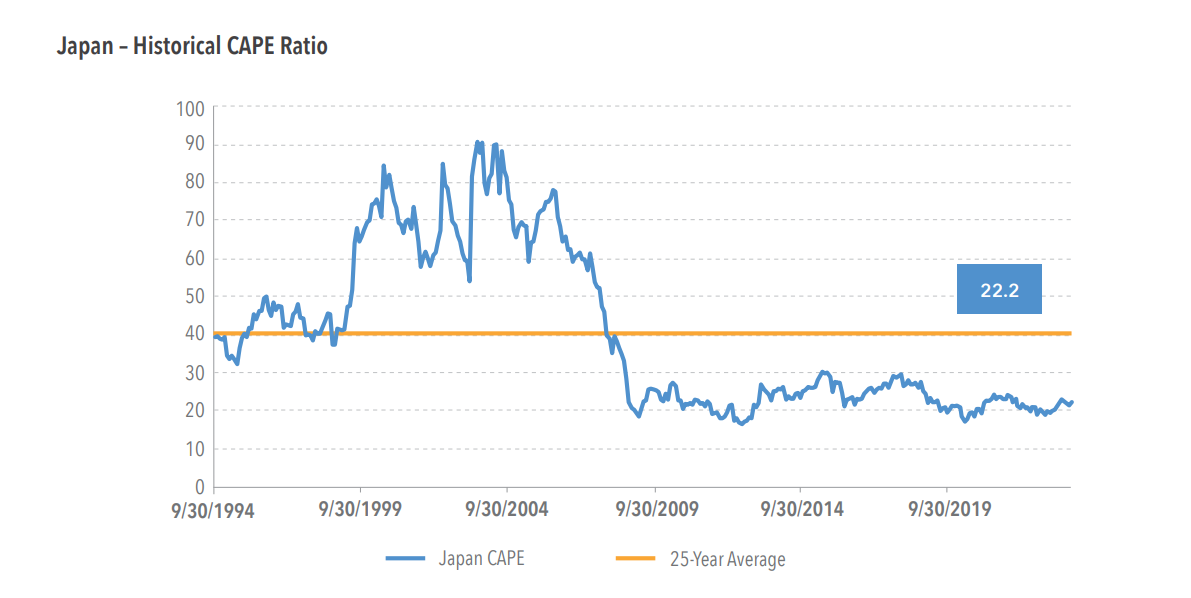

Look, the Japanese valuations had gotten absolutely bonkers. And high valuations in the present pull returns from the future. That’s about as close to an iron-clad law we have in finance. That is why it took three decades for them to reset.

Our valuations are nowhere near as crazy, no matter how ridiculous they seem!

India CAPE Ratio

Know your history!

Let me leave you with three of my favorite quotes on how to think about history:

“There’s nothing new in investing, only investment history you don’t know.” — Larry Swedroe

“I really don’t like the term Black Swan and the reason why I don’t like it is because you only see black swans in the history you haven’t read. What we’re looking at financially is not any different than what we’ve seen before.” — William Bernstein

“Nothing in life is as important as you think it is, while you are thinking about it” ― Daniel Kahneman

Sooo true!

The problem with investing is that we make decisions with money, and money is an emotional object. Money is not just coins, pieces of paper or numbers on a screen. That’s the form factor of money. Money is really a receptacle of our fears, hopes, dreams, anxieties and aspirations.

Every investment decision we make is tinged with these elements. Nobody invests to make money. They invest to go on that vacation, save for their kid’s education or marriage, or to retire in Goa by a beach-side shack. Every bet we make with money has an objective with a different emotional intensity.

When markets rise or fall, so do the odds of you being able to hit your goal. By extension, so does the emotional intensity of what you experience. This is what makes investing hard — it’s not your inability to pick stocks or funds. As paradoxical as it sounds, that’s the easy part.

In my experience, the one thing that helps you deal with market volatility is knowing some financial history. What history teaches you is that there is nothing new under the sun. What you consider a massive rise or fall is an event that has occurred a million times before. History shrinks your ignorance and arrogance. It removes your blinders and normalises a lot of things that you otherwise consider unprecedented.

Knowing that bad things happen, and can happen frequently, is essential to surviving in the markets. And surviving is key. You can only make money if you stick around long enough.

Why do we make all these mistakes despite knowing deep down that they are wrong?

Stay tuned for my next rant.

Takeaways

- Don’t take all-or-nothing calls. Trust me, you’re not that smart. It’s humbling to accept that you are not smart but financial success is downstream of humility.

- If you think the markets are overvalued, rebalance. Sell equities and rebalance into debt. Unless you’re skilled at market timing, taking in-or-out calls is dangerous.

- Are you a trader or investor? As dumb as this question sounds, if you don’t have a clear answer, you’re in trouble. The skills required to succeed in trading are not necessarily the same as those you need for investing. Know what game you are playing.

- The loudness of a person and their knowledge is inversely proportional.

- Lazy investment choices and decisions can only end in one way—tears!

- Wherever you feel like doing something, don’t! Sleep on it!

- Before you make a financial investment, ask ChatGPT if it’s a good idea. Trust me, it’s better than most other idiots that claim to be experts.

So, what do you think?

I appreciate your critique of the ”sell everything” crowd, but I believe it’s overly harsh—especially when viewed through the lens of your own data and the realities many investors face. Your previous post, a brilliant analysis, highlighted speculative excesses like F&O volumes at 60x the cash market, making a clear case that we hit a peak late last year. For many, selling then wasn’t panic; it was a rational response to the evidence.

As Nitin noted on X, markets swing between extremes. After a 30-60% Q1 crash, those who avoided the frothiest bets likely still hold long-term gains. But if the pendulum swings further, those gains could vanish. Holding on risks turning a reasonable win into a loss.

Consider Zerodha’s readers: many juggle long-term debt like mortgages (or worse, high-interest loans), face potential income disruptions from macro shifts or AI, and hold portfolios that, while hefty at 10x their annual income, don’t exceed 3x their obligations.

For them, selling now—locking in gains and awaiting a better entry—could be the only prudent move.

Contrast this with the extremes: Bogle’s ”SIP and forget” ignores today’s volatility, while traders betting the house on expiry-day OTM puts gamble recklessly. There’s a wiser middle ground—like the 200 DMA you mentioned—that balances risk and reward for those paying attention.

Dismissing the ”sell everything” call overlooks the context your own work provides. For many, it’s not dogma—it’s prudance.

testt

test2222

Helloo

Amazing content like always