A People’s Republic?

This post is the second part of our series ‘Big Trouble in Brittle China’, which covers the many problems that are visiting the Chinese economy today. Click here for part one, where we began with China’s reliance on investments as a driver of growth.

Let’s recap.

China invests more than two-fifths of its GDP into its economy every year. This was the right thing to do a few decades ago, when it needed large sums of money to build things from scratch. With time, however, there are fewer places where urgent, large investments are needed. Nevertheless, its strategy remains the same. Alas, these investments are no longer successful in bringing it the sort of explosive growth China enjoyed for decades.

This week, we turn to the single defining characteristic of the Chinese economy in the eyes of the world – its status as the factory of the world. We’ll see why exports are no longer the engine for GDP growth they once were, and ask whether China’s own domestic markets could be its answer.

Two: China doesn’t make for the world as it once did

Don’t get this wrong: China remains the world’s sole manufacturing superpower. Almost a third of the world’s goods are made in China. But while Chinese manufacturing thrives, it no longer holds the same place of pride in the Chinese economy.

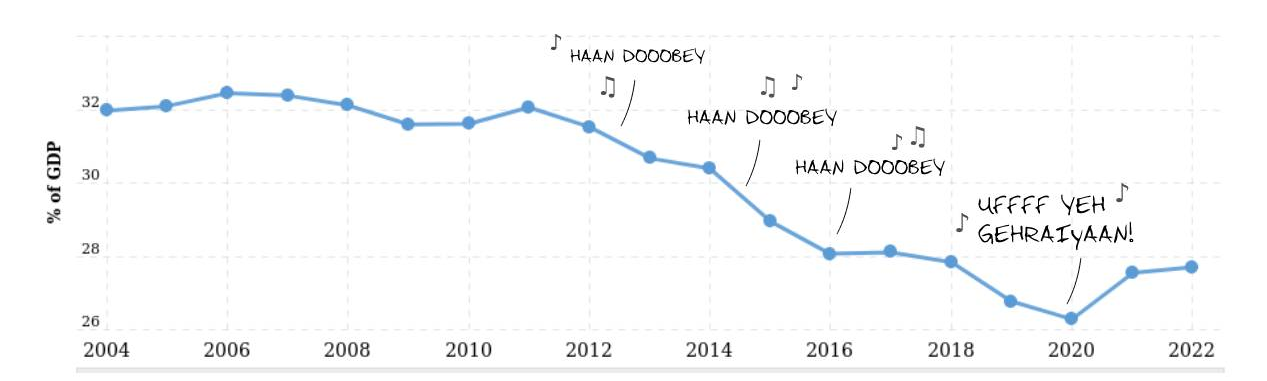

Chart by Macrotrends (link), defaced by us.

Chart by Macrotrends (link), defaced by us.

There was an era when the country’s entire economy was geared around making an ever-widening number of things to sell to the world. With an infinite supply of extremely cheap labour, heavy government subsidies, an artificially depressed currency and steady investments in logistics, there was no better place on Earth to manufacture at scale for foreign markets. By the mid-2000s, a fifth of everything China made was meant to be exported. These exports were worth more than a third of its GDP.

Then the year 2007 came about, and the global economy broke.

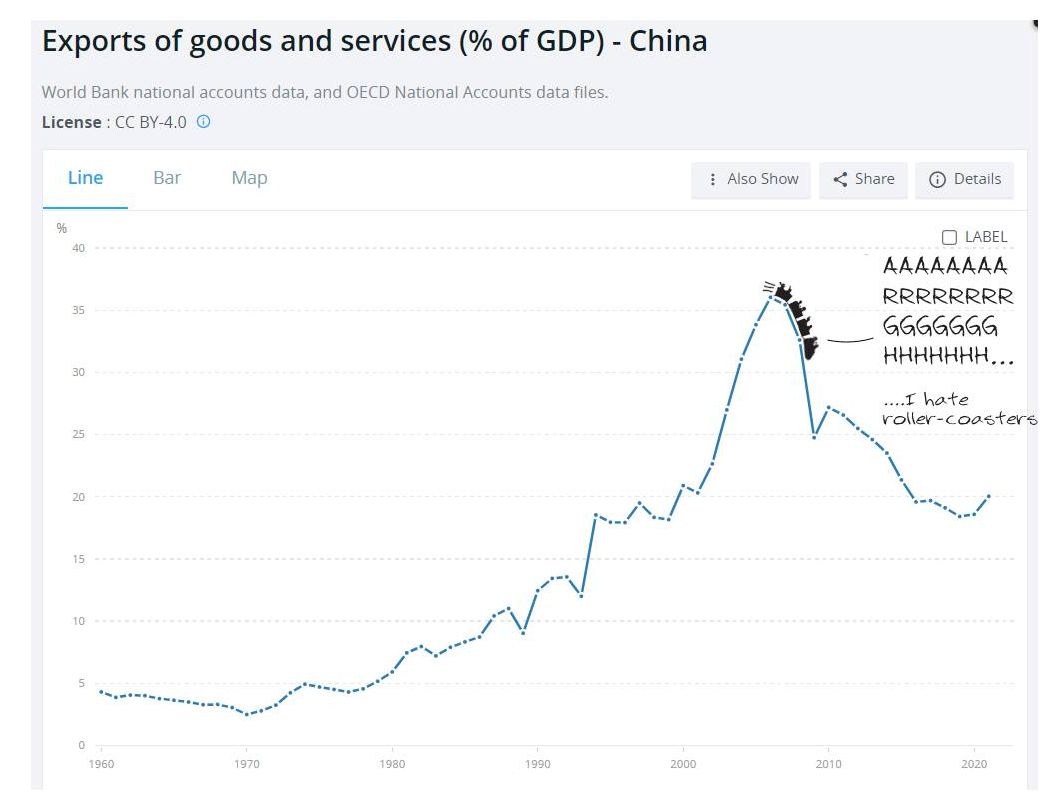

Chart by the World Bank (link), defaced by us.

Chart by the World Bank (link), defaced by us.

Suddenly, the developed world could import less from China. Exports fell off a cliff – dropping by 17% in the year 2009. 20 million Chinese workers lost their jobs. Even as the crisis eased, advanced economies – the most profitable markets for Chinese goods – saw patchy and uneven recovery. This placed a limit on the extent to which Chinese exports could recover.

They’ve never recovered to the same level. While China continues to manufacture at a relatively high clip, it increasingly does so for its own markets. The fraction of Chinese goods reaching foreign markets, today, is only marginally above what it was in the year 2000. Poorer South and South-east Asian countries now have the advantages that China once did, and they’ve taken over cheap exports – once a Chinese specialty – as China moves to more sophisticated, higher-value products.

To an extent, this was bound to happen – with or without a global crisis. It was unhealthy for 40% of an economy of China’s size to be exporting goods. The country had to correct its course at some point. Moreover, China had a way out. With over a billion people that were quickly growing rich, one hoped that China’s own domestic market would demand enough for this shift away from exports to barely matter. And they have softened the blow, to an extent.

China’s own consumers, alas, don’t quite behave like those from the developed world.

Three: The Chinese save a lot of their money

Imagine you’re an average Chinese person.

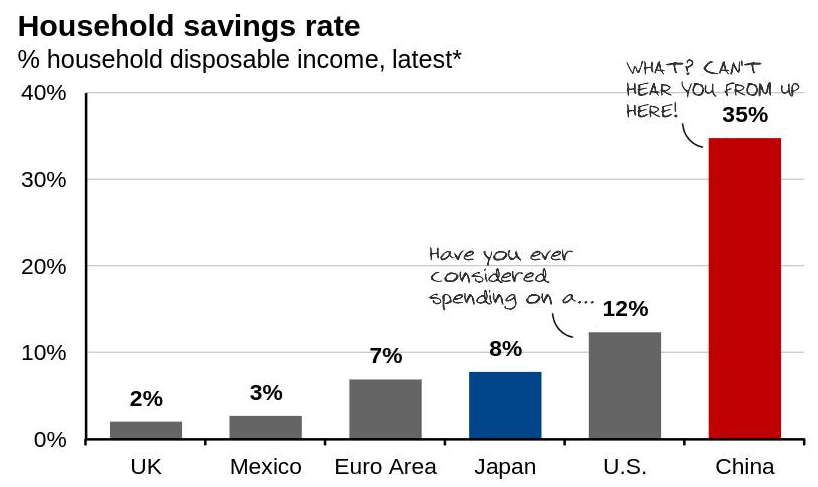

You’re expected to fend for yourself. Your entire culture tells you to plan for the future, to ensure that you and your family are secure. It has seen too much upheaval to simply trust that things will be alright. Despite its purported communism, Chinese social security is riddled with holes, and is coming under increasing levels of strain under its aging population. With the one-child policy sticking around for as long as it has, and fertility remaining stubbornly low, you can’t really bank on future generations to see you through your old age either.

What do you do if you have any money? You save it for a rainy day, of course.

And thus, China has one of the highest savings rates in the world.

Chart by JP Morgan (link), defaced by us.

Chart by JP Morgan (link), defaced by us.

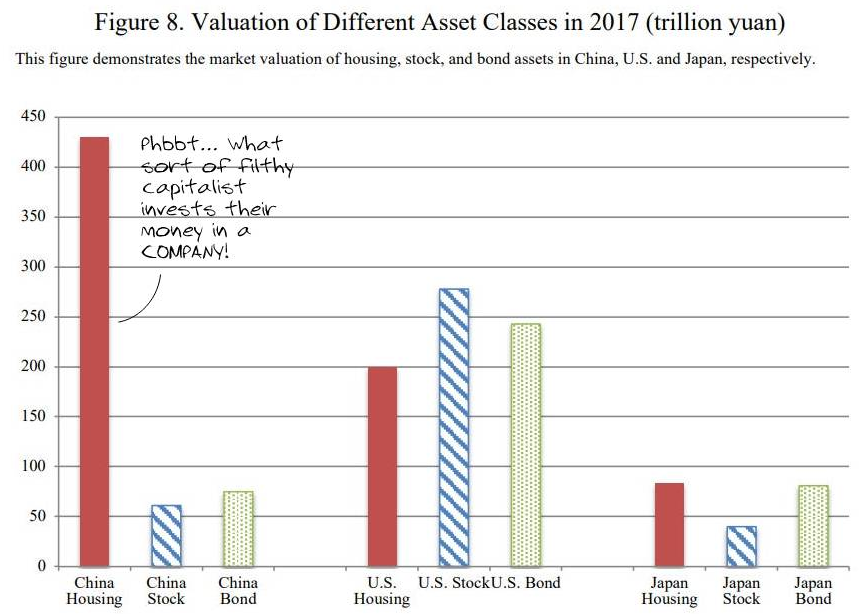

Moreover, ordinary Chinese people do not trust stocks and bonds. China’s companies see frequent and heavy-handed intervention from the Government, making it hard to predict the future of any one security. Chinese stock markets also lack a solid base of institutional investors, making them severely dependent on the whims of retail investors. As a result, they are far more volatile than other major markets.

Chinese stock markets, therefore, have earned a reputation of being casinos. The money the Chinese save goes into property. The money they gamble goes into stocks.

Chart by Rogoff & Yang, NBER (link), defaced by us.

Chart by Rogoff & Yang, NBER (link), defaced by us.

All this saved up money, unfortunately, further distorts China’s economy.

As we’ve seen repeatedly in countries across the world, it is a bad thing for too much money to be available too easily. China’s extraordinarily high savings rate created such a situation. We talked, last week, about China’s addiction to investment-led growth. The money to sustain this addiction came from savers. The savings of Chinese households created a giant pool of money for its financial system to give away. Over time, it got complacent, and gave money to projects that could no longer bring the returns China was used to seeing.

Four: China doesn’t make much for the Chinese

Not only do the Chinese spend less, relatively less money reaches them in the first place.

There is a cost to having so much of a country’s GDP being pushed into investments. See, an economy carries a finite amount of money. When governments and corporations free up money to invest, it comes at the cost of the ordinary consumer. Chinese businesses pay workers less than they do elsewhere. State-owned enterprises, instead of paying dividends to the government, retain and reinvest their profits. Because of this, the income of Chinese households has grown far slower than the country’s GDP. While the money that is thus freed up can be pumped into the economy, it comes at the cost of regular Chinese people.

On top of that, as we just saw, the little disposable income that consumers have is saved up – and reinvested in the economy.

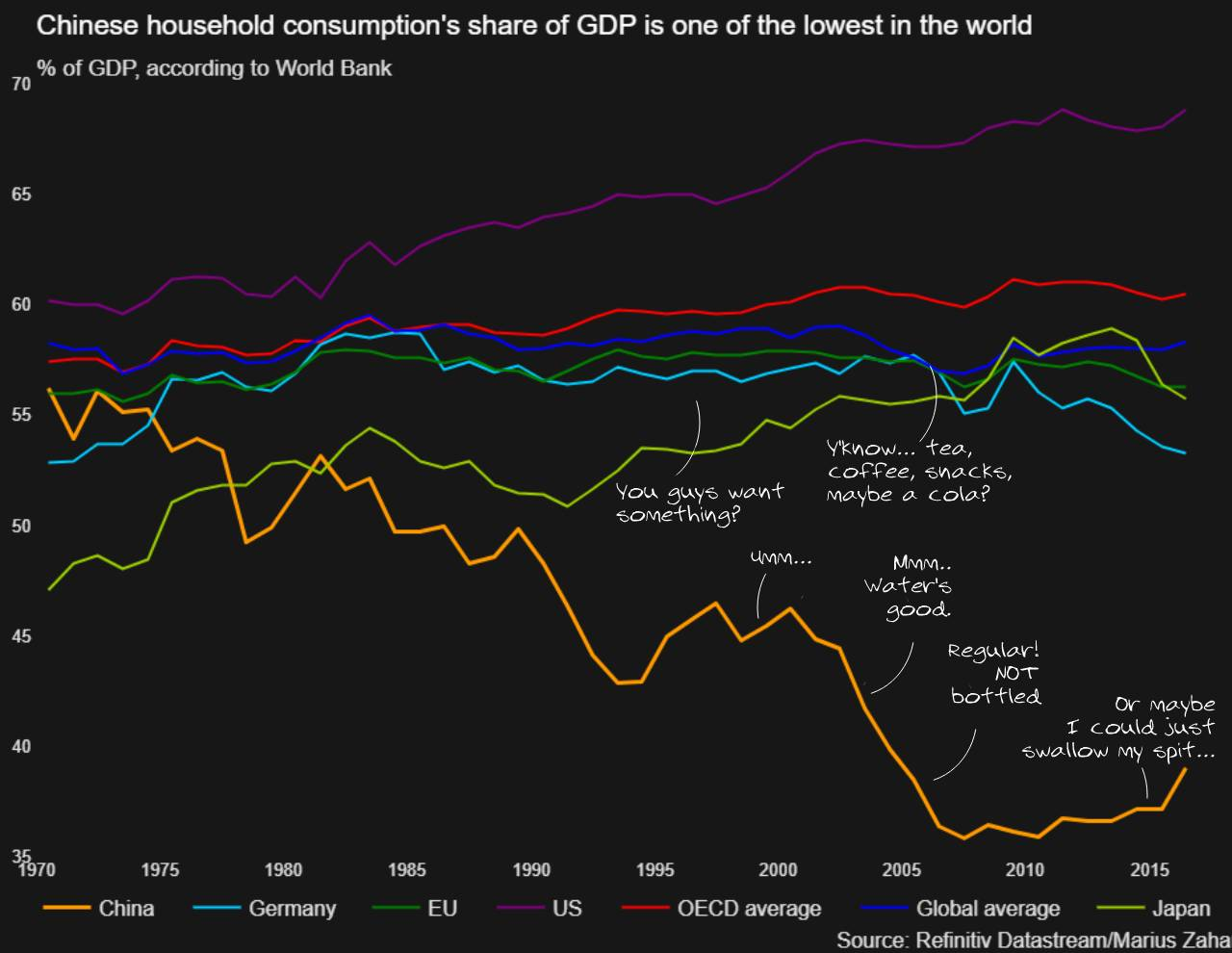

All of this means Chinese consumers buy surprisingly few things for an economy of its size.

Chart by Reuters (link), defaced by us.

Chart by Reuters (link), defaced by us.

Of course, with over a billion consumers, the Chinese domestic market is still the envy of the world. And in the years before the pandemic, it was even growing at a healthy clip. But for its gargantuan manufacturing sector, it is no substitute to advanced economies. It has never been deep enough. If China wants to manufacture at its current scale, it has to look for markets abroad.

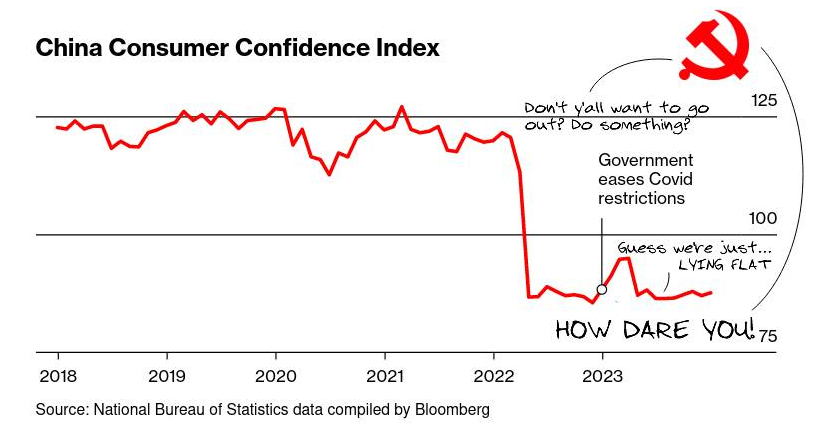

This was true before the COVID-19 pandemic. The country’s zero-COVID policy made things far worse. With brutal, unending lockdowns, and little Government support for livelihoods, Chinese consumers have been an exceptionally pessimistic lot off late. Easing COVID restrictions hasn’t made much of a dent. Prices have fallen for the last four months, and – as we explained here – that is not a good thing.

Chart by Bloomberg (link), defaced by us.

Chart by Bloomberg (link), defaced by us.

Chinese policy-makers are worried. Only a few days ago, its Government proposed a year-long program to boost consumption in the economy.

But this isn’t a new problem. It was a concern fifteen years ago as well, when the global economy had crashed and export markets could no longer be relied on. Back then, instead of wooing people to buy consumer goods, it gave them the one thing they would willingly splurge on: houses. Next week, we’ll see what that choice has meant for the Chinese economy.

The map of China used shows India’s area as part of China.

Please change the map or take down the post.

How can such a big company share such map which shows India’s integral area as part of other country.

Hi Ketan, thanks for pointing this out to us. We have replaced the image.

India’s consumption growth has slowed even as govt capex boomed. Isn’t this somewhat similar to what has happened in China at a much bigger and graver scale?

Hi Sarthak, thanks for writing in!

I don’t think one should compare the two – India and China are in very different phases of development. There was a time when heavy state investment was the right thing for China, and it reaped massive dividends by doing so. That period ended. When it was coming to a close more than a decade ago, key Chinese policy-makers – including Wen Jiabao – were calling for a re-balancing of the economy towards consumption. Alas, it is difficult to pivot away from something that has worked beautifully for decades. It didn’t, and now finds itself in a crisis.

Perhaps India will face the same tough choice some day, but I don’t think we’re there yet. If there’s a lesson to draw here, it is to stop being fixated with simple, high-level, one-size-fits-all recipes for economic growth. Those don’t exist. If you lose sight of the specific problems you’re dealing with, you’ll make mistakes.