18.1 – Recap

We started chapter 1 with an introduction to financial modeling. I did talk about how financial modeling is always taught to students in a classroom program. An attempt to explain financial modeling in Varsity’s long-from approach was an interesting experience. The module took maximum planning and several rewrites, but I hope you recognize the complexity involved in this module 😊

As we approach the last chapter in this module, let us quickly recap everything we have learned so far in this module.

- As a first step, we discussed how to set up the excel sheet for building a financial model. We discussed format hygiene and how important it is to ensure cells are systematic across sheets. For example, column J represents Year 6’s data in sheet 1; then, we ensure column J is linked to year 6 data across all the sheets.

- We moved to import the historical data from the annual report. We copied mainly the P&L and Balance sheet statement. Just to let you know, there are multiple places where you can source these financial statements, including 3rd party websites. But the best source for getting this information is the company’s annual report. So always try and stick to the annual report. We also color-coded assumptions and calculated numbers.

- We set up an assumption sheet, where we dumped all the assumptions on one page. The page itself is divided into P&L assumptions and Balance sheet assumptions. We discussed two techniques of assumption – the growth driver by taking historical averages and the percentage technique.

- For some companies having a dedicated revenue model helps. A revenue model gives us granular insights into things that can impact the company’s revenue.

- We built the asset and debt schedule of the company. Asset schedule gives us insights into depreciation and CAPEX. The debt schedule gives us insights into the cost of debt. Both these sheets link back to the balance sheet.

- The Reserve schedule is another schedule we built, with numbers from both P&L and balance sheet.

- With all the schedules and assumptions in place, we make P&L and Balance sheet projections. At this stage, all the line items in the P&L and Balance sheet get projected. What remains are the cash and cash balance numbers on the balance sheet.

- We built the cash flow statement using an indirect method to get the cash balance. The final cash value flows back to the balance sheet, and if the calculations are correct, the balance sheet should balance at this stage.

- The financial model is said to have hit a milestone when the cash value hits the balance sheet to balance the balance sheet.

- After the cash flow statement chapter, we discussed the theory of valuations, and now, it is time to implement the valuation model and bring all the concepts together.

Over the last few chapters, mainly from chapters 14 to 17, we discussed theoretical concepts related to valuation. In this chapter, let us implement the discounted cash flow valuation (DCF) model within the primary model. The output from the DCF model is the share price of the company.

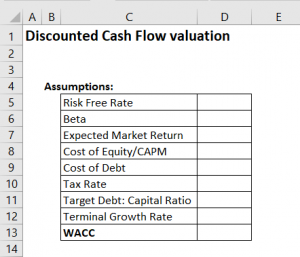

18.2 – Assumptions

From a format perspective, the DCF model sheet will look a bit different from the rest of the model sheets because we are not dealing with any historical data. However, as usual, we will start by indexing columns A and B and rename the sheet to ‘DCF valuation.’

To begin with, we will dump all the data we need to implement DCF.

I hope you’ve read the previous few chapters so that these terms don’t suddenly look alien to you 😊

- We can use the long-dated Govt securities (bond) yield as a proxy for the risk-free rate. The data is available for you on RBI’s website. As of today, I’ll take the 10-year bond’s yield as a proxy, which is at 7%

- The beta of the stock is pretty easy to calculate. I’ve explained it in this chapter here. Refer to section 11.5. I’ll assume the beta of the company we are modeling as 1.2. As you may know, a beta of 1.2 is high beta. But don’t worry; you can change these numbers anytime since this is an integrated financial model.

- The expected market return is the standard market expectation and can range between 10% and 12%. Let us go with 12% for now.

- The cost of Equity is derived from the CAPM formula discussed in the previous chapters. It is the risk-free rate plus the difference between the expected market rate and the risk-free rate multiplied by the company’s beta. It is easy if you look at the excel formula.

- The cost of debt is the rate at which the company borrows funds—assuming this to be 10%.

- The tax rate is 25%. Of course, you can change this to any percentage you think makes sense.

- The target debt-to-equity ratio is assumed to be 50%. While it’s nice to be debt-free, most companies cannot afford to be. They do end up taking debt to fund CAPEX, but a well-run company will aim not to cross the 50% threshold.

- The terminal growth rate is a super important assumption that we make. The entire DCF model relies heavily on this assumption. As discussed in the previous chapter, we will assume the terminal growth rate to be close to the long-term inflation number of the country, so between 4 and 5%.

- The weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is something that we will calculate in excel directly. But I do hope you recollect the discussion we had previously on WACC.

WACC is the weighted average return expectation of debt holders and equity holders (check highlights). We will use the WACC to discount the cash flows.

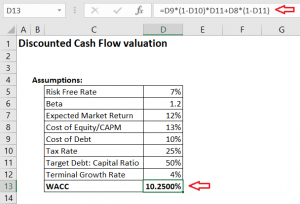

18.3 – Free cash flow to the Firm

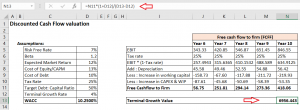

Once we have the assumptions in place, we have to calculate the free cash flow to the Firm (FCFF). Remember, we are calculating the future free cash flows to the Firm. Hence we have to deal only with data from year six onwards. We start the calculation with EBIT and take the tax shield effect on EBIT.

Of course, we have not calculated EBIT specifically in P&L, so we will have to quickly figure that in P&L. EBIT is earnings before interest and taxes; hence to calculate EBIT, we subtract all the expenses from total income, except the interest.

We multiply EBIT with (1-tax rate) to factor in the tax shield effect on EBIT. To this, we add back all the non-cash charges and deduct working capital and CAPEX charges to arrive at the free cash flow to the Firm. I’ve made these calculations in excel, and here is how my sheet looks now –

Notice that I’ve indexed columns E,F,G, and H to ensure I link columns J to N with years 6 to 10, just like in the other sheets. You are free to format this sheet in whatever way you think makes sense.

EBIT and depreciation numbers come from P&L. The working capital and CAPEX numbers come from the cash flow statement. I’ll provide the link to download the excel sheet at the end of this chapter, so please do download the sheet and check the cell linkages.

18.4 – Terminal Growth value

We now have the free cash flow to the Firm, projected up until the next five years, i.e., till year 10. However, this does not mean the company will stop generating free cash flow after five years. We assume that the company will not only continue to exist but will also continue to generate free cash flow. The rate at which the cash flow grows is called the ‘terminal growth rate,’ which is usually equivalent to the long-term inflation value of the country.

I want you to use a bit of imagination here. Fast forward to 5 years from now. From the 5th year onwards, you are looking outwards at eternity and imagining all cashflows that the company will generate. You need to sum up all the cash flow and bring it to the 5th year, i.e., the current year.

You can do this by applying the terminal growth value formula –

= 5th Year cash flow * (1+terminal growth rate)/(WACC-terminal growth rate)

I’ll not get into the technicalities of how the formula is derived. But that’s the formula to figure out the sum of all the future cash flows.

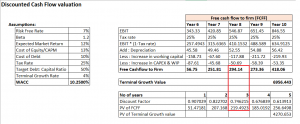

Here is the calculated value –

The terminal value is a big number and has an impact on the final valuation of the company.

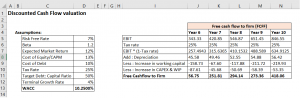

So, we have the next five year’s free cash flow to the firm numbers. We also have the terminal value number. We now have to discount all these cash flows and bring them back to the present-day terms, i.e., we need to calculate the present value of all the future cash flows.

For example, the free cash flow in Year 8 is 294.14 Crs. Year 8 is three years away from the present day. To calculate the present value –

= 294.14/(1+10.25%)^3

= 219.4923 Crs.

We can do this systematically in excel –

I first calculated something called a discount factor, which is –

1/(1+WACC)^(time)

The time for this particular example is three years. So the discount factor for year 3 is 0.746. I have to multiply the discount factor with the free cash flow to get the present value.

So 0.746 * 294.14 = 219.4923Crs.

Notice that I’ve also calculated the present value of the terminal growth value.

18.5 – Share price

We’ve come to the last bit, finally 😊

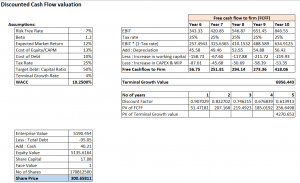

We sum up all the present value of the future free cash flow, i.e., from Year 6 to 10, along with the current value of the terminal value to arrive at the ‘Enterprise Value. We deduct the present-day debt from the enterprise value and add the present-day cash to give equity holders the free cash flow.

The present-day debt and cash value come from the balance sheet.

And, here you go –

The share price is Rs.300. What does this mean?

The price you see here is an outcome of the entire valuation exercise. We have made many assumptions here, and if these assumptions are made intelligently, then with some confidence, we can conclude that Rs.300 is the fair value of the stock. You can now compare the stock’s market value on the stock exchanges and decide to buy or wait. For example, if the stock is trading at Rs.425, then you know that it is overvalued compared to its fair value; hence you can avoid buying the stock.

If the stock is trading at Rs.225, the stock is undervalued, and you can go ahead and invest in the stock. Or if the stock is trading at Rs.300, it is said that it is fairly valued.

18.6 – Closing thoughts

The model we have built is integrated, meaning that any change in any number in this model will impact the share price.

For example, in the assumption sheet, I’ll change the material consumed as a percentage of sales for Year 6 to 60% from 65%. The share price will change to Rs.462 from Rs.300.

Or I can change the terminal growth rate to 4.5% from 4%, and subsequently, the share price changes to Rs.323. I encourage you to make these changes and see for yourself, which is the beauty of this model. All the sheets and numbers are linked, and any difference across the sheet will result in the final output.

You can make these changes when you think the difference is justified, which brings me to my next point.

Building a financial model is pretty straightforward. A seasoned modeler will probably create a good model in a few days. But what is essential is to keep the model up to date. Once you build a model, track the company closely, especially the management interviews and statements. Whenever new information comes, make an appropriate change in the model.

For example, during the following quarterly result announcement, the company may say they want to slow down their CAPEX spending. Immediately, tweak your model and adjust for a lower CAPEX spend, and accordingly, the share price changes and gets re-rated. Maintain a separate sheet in the workbook detailing the reasons based on which you made the changes. The sheet acts as your working notes.

One last thing before I end this chapter and module – the final output, i.e., the share price is Rs.300. That does not mean, Rs.300 is strictly the fair value of the stock. The share price is an output of a model we have built, and the model is undoubtedly prone to inadvertent errors. Therefore, you need to factor in model errors. I’d assign a 10% band as a modeling error, which means I’ll consider the stock’s fair price anywhere between Rs.270 to Rs.330.

I’ll be happy to buy the stock anywhere within this range, preferably at the lower end, as it gives me some margin of safety.

I hope you enjoyed reading through this module as much as I enjoyed writing this for you.

You can download the excel sheet from here.

Key takeaways from this chapter

- The stock’s beta represents the stock’s riskiness with respect to the market and can be easily calculated.

- We use the CAPM equation to figure out the cost of equity

- WACC is a blended cost of capital that we use to discount the cash flow

- Free cash flow to the Firm is calculated by starting with EBIT

- You can calculate the discount factor to calculate the present value easily

- Enterprise value is the sum of all the present value of future cash flow

- As and when new information flows, one needs to update the model

- The final share price is just an indicator of fair value. It makes sense to factor in model errors and assumes a fair value price band rather than a since price as the fair value of a stock.

Hello Karthik Sir,

It\’s been a while now, I am using Zerodha Varsity, to enhance my financial literacy, I have even completed few cerficiations from the Varsity, thanks to you and your team to making such difficult concepts very easy, was just curiuos to know will the modules such as sector analysis and financial modelling will be interaged to Varsity applicantion, as it becomes convenient to understand and keep a track on our progress

Hi Krish, yes, the idea is to bring this into the app. We will do it soon 🙂

Also, happy to note that Varsity has been helpful to you!

All the content on this website is amazing! Can you make a module/video on AI for finance?

Do keep an eye out on our Youtube channel 🙂

Hey Karthik,

Thanks for the amazing module!

One question – what is the key difference between using an integrated financial modeling technique for valuation vs the DCF technique for valuation discussed in chapters 14 & 15 of the \”Fundamental Analysis\” module? Is it just that in FA module, we projected the the FCF with assumed growth rate (18% for first 5 years and 10% for next 5 years) and here we are deriving the growth rate via assumptions?

Thanks Vishal. Think of the Financial module as a technique to develop deeper, granular view on the financial statements, while FA gives you deeper insight into the business as such.

Hello sir,

I just wanted to thank you for this amazing module, clearly you have put immense effort into writing this module and you have done an amazing job with it.

btw i got a value of 178.84 from my model

Thanks Shlok, I\’m glad you are liking the module. Happy learning!

Sir I am recently see this module and want to comment for uploading PDF for this module. But after seeing these comments from 2022, have no hope for the PDF now. Really surprising and also disappointing as I have a very good and genuine image of Zerodha. Hope you serve better without giving false assurance like this. Thanks and looking forward your response.

Hi sir,

Thanks for the wonderful explanation. Just curious to understand while calculating terminal cashflows, we are not considering any release of WC that means, we are forecasting that company will continue to invest in WC at the same pace even if the growth is moderated to 4%?

Yeah, thats sort of true. The thought process is that the company hits a steady state and continues that way 🙂

If i calculate PE ratio based on share price and profit projections of my model it shows a PE very less than market PE…why its so…do i need to adjust it to make it to market PE levels using PE formula…pls clarify…

Yeah, some parameters will be off. YOu need to check that. Also, if you have faith in your model, you may stick to it and not change 🙂

If i use 5yr historical data and forecast upcoming 5yrs and calculate dcf and it comes out 500rs does that means companys present worth is 500 or its the worth after 5yrs…pls clarify…

It is 500, as of today and not 5 years forward.

Which company\’s Financial Model is this, asking cause it would help to better understand when to make which schedule for beginners

Think of it as a generic manufacturing company 🙂

How to calculate the share price?

We have explained it in the model.

Sir right now !! I am stuck at cashflow because of mismatch..

But I read through valuation concepts.

Right now we have assumed various things like let cost of debt be 10%, but if i want to calculate it how can I?

and I dont understand this target Debt to capital ratio ?

Thats the point of an integrated model Harsh, you can change these parameters and see how the valuation changes. Target debt to equity is basically an idea ratio of debt and equity in the company\’s financing structure.

No worries, sir you have already given us so much..

Happy learning 🙂

That was a great module sir, thanks for it

Btw from where I can download the PDF for this (for revision purpose)

Because When my net go Down then i think of study and if i had a pdf downloaded then i can use that free time to revise these concepts 🙂

Thanks Harsh. Unfortunately we dont have the PDF version for this just yet. Will try and do it sometime soon.

Hi,

wanted to know if i want to buy stocks or select stocks for long term or getting a multibagger. Is this the only way to find the price range of undervalued stock? can the valuation go wrong as well?

This is one of the ways, not the only way. Yes, the valuation can go wrong, hence you need to put enough checks and balances in place to ensure your financial model is as realistic as possible.

Thank You Karthik Sir for such a wonderful module.

Happy learning 🙂

Hi Karthik,

I hope you are well at the time of writing this comment. I wanted to know that are there any other chapters coming up in the series? Also, can you create a pdf file too like the other modules have? I personally really like this initiative that zerodha has taken to increase the financial awareness through your varsity program. Thank you so much to you and the team who is making such a quality content for all of us. Excited to next chapter in the series!

Thanks Chirag. All well 🙂

No more chapters in this module. Is there anything specific you are looking for? Will be happy to include that.

If a company acquired a subsidary wouldn\’t it change our forecasting as the new company will have impact on multiple line items of all financial statement.Amar Raj Batteries acquired a subsidary in 2023,so the trends for 2023,2024 different from before that.Since we use year on year growth,wouldn\’t it present us with a skewed picture.Also how to forcast in such scenarios for the next 5 years if 2 years ago a subsidary is added and financials are different.

Yes, it would. Hence you need to factor in the consolidated reports for this.

Sir,

Is thre a firm giving out dcf calculation models for each Indian firm.Thanks.

Dont think so, but please do check Screener or Tijori finance once.

Hi karthik,

Fantastic work like always!

I have gone through Fundamental analysis module and then jumped to this module. DCF analysis explained in FA module is quite different from what you have shown in this module.

With the help of FA module learning, I have prepared an excel sheet for myself. By just feeding few values from annual report, i will get all the financial ratios and also the checklist qualification and the DCF analysis.

when I started this module, I made up my mind that I will use the FA excel sheet to compare companies from sector as that excel is not time consuming and I will do detailed interated financial modelling (extrapolating past 5 years to next 5 years) for the stocks that I filtered out through financial ratios (with the help of my excel sheet).

But now, since the DCF analysis explained here is quite different from FA module, I\’m just confused to proceed further.

I agree that DCF analysis through IFM, will be close to accurate because we are extrapolating each entities and arriving at FCFF. If I use the DCF analysis method from FA module to save time, will that be useful for me in any sorts or that is just out dated and won\’t yield appropriate results?

Please help me on this.

Hi Gautham, both are more or less the same. This one here is a bit more nuanced as it covers from a financial modelling perspective. But if you find the method explained in FA easier, the please do use that, your results should not vary much.

Legendary Stuff brother….Big standing ovation for you for doing this for all the enthusiasts. Cheers

Thanks! Happy learning 🙂

Hii Karthik,

Can you please confirm the below:

1. How did we arrive at the cost of debt at 10%. By taking the rolling average of interest paid being paid?

2. Will the tax rate be fixed at 25??

3. Target Debt: Capital Ratio will be fixed at 50 or will this differ from company to company or sector to sector?

4. And can we create a model for any company similar to what we have created in this module. Or are there any exception for this model not being applicable anywhere?

Thank you Karthik for a great learning experience.

1) You can get this from the debt schedule or yes, by taking the average of the interest (cost of debt) as stated by the company in its annual report.

2) No, this will change

3) This is an assumption. This will change from company to company.

4) Overall direction remains the same for most companies, except for maybe banks and NBFCs.

Sir, I kindly request you to share with us the excel for few more imaginary or real company finance modelling along with valuation to educate us. This will help me to practice and verify whether my calculations are correct, as I am very new to this whole subject. Thanks a lot for the great effort. Regards Suba

Suba, noted. Will try and do, thanks 🙂

Hi Rangappa Sir, Thanks for this DCF module. For excel sheet can you please provide any real example of a company share so it would be helpful to corelate. Also is there any easy way we can fetch following data of any company i.e. P&L, cashflow and Balance sheet etc to this excel.

Why dont you use this model and build on a real company? Pick a simple company to begin with.

Please include a PDF document for integrated financial modelling. Thank you.

till when can we expect a pdf for this sir? its been years since this module came out. would help a lot if you share it soon.

Will take it up soon.

please provide pdf for this module sir. rest the course is really good and thanks a lot for helping out there. hope to get the pdf soon.

Sure, noted.

Hi Karthik

Why would we need to incorporate tax shield in EBIT? EBIT anyway is \’before\’ interest and tax, so like we were adding all non cash expenses to PAT to arrive at FCFF, we would not need to do the same when we are using EBIT to calculate FCFF

The actual tax outflow reduces and PAT increases hence. Have explained in the chapter I guess.

Thank you soo much sir!!! Recently the companies that have changed there financial year are ACC Limited, Amubja cement. I have come across these 2 companies till now while selecting a company to build my first financial model.

sir it would be great if i can get your email id its much more convenient to ask you doubts on email directly.

Devansh, you can share your queries here itself, I respond to all queries here 🙂

sir this financial model contains financial year starting from April and ending in March. Now few companies have changed there financial year ending in December to ending in March, and therefore there report contains data for 15 months period. so will there be any problem if I input 15 months data in one column and rest other columns with 12 months data?

No, the structure of the model remains the same right? Which means the way in which you build a financial model remains the same. Also, which company are you talking about? Indian FY is from 1st April to 31st March.

16.2 : FCFF = EBIT *(1-tax rate)+ Depreiciation + Amortization + deferred taxes – working capital changes – investment in fixed assets (CAPEX).

1. While calculating FCFF in above excel sheet, deferred taxes were not added

2. Is enterprise value is of current year (5th year) and aslo enterprise value and Market cap same?

3. what does terminal growth value number (6956.443) signifies?

4. Is FCFE and Equity value same if not What is FCFE in above excel sheet

1) Yes, thats becuase you cant really forecast deferred taxes.

2) Yes. Market cap is based on market\’s perception and Enterprise value is based on the book value.

3) It signifies the cash the company will generate through its life.

4) If you divide FCFE by number of shares, you get equity value on per share basis.

What is the difference between the value of the share we derive by using the Cashflow, NPV and FV values we used in FA module VS this module? Which method tends to be more precise?

I personally prefer cash flow basis as its based on the actual cash in the company.

Sir, is the valuation link I sent few days back accessible? Any comments?

Please upload pdf of module so that we can read without straining eyes and mark important information

We will, thanks Jay.

I have approved your request sir. This is the first time, I shared something like this on Google drive. So had no idea that restrictions had to be modified too. Just found that out.

Sure, thanks. Will try and go through it.

I\’m resharing the file sir. I don\’t know why the previous link was not accessible. But if you can, please consider downloading the file in your hard disc in case the link doesn\’t work again.

Valuation Model Link👇

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1KkQgzRTxDMWoXvQNPlgZ-YR7NQwWz5ro/view?usp=drive_link

Link To The Valuation Story👇

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Q6dLRnXDVrBo2JLrf1Pw8ddAKDo4HzqP/view?usp=drive_link

(I understand that this request is a big ask considering your busy schedule answering all these questions and making those videos among your other work. But I thought if I keep admiring at my own model, I won\’t be able to find any flaw. Also I have no people to ask either since I live in an environment where people consider equity investing as gambling. So I thought the best person to judge this is the person I learnt from, hence my request.)

Sure Sathish, will try my best to check. But still no access, I\’ve sent a request for permission to access the file. Thanks.

Hello Karthik

Thanks for the reply.🙏

Can I know the reason for suggesting the model in FA ?

Also in FA we are considering the terminal value from 10th year whereas in integrated financial modelling we are considering from 5th year. Why so? And from both the models, I get different values.

Varun (Bengaluru)

You can choose either 5 or 10 years, and yes, both will give different results. There is no right or wrong answer to this. However, 5 years the predictability factor is better than 10 years, so maybe that leads to better DCF model as well.

Sir, I requested for your valuable feedback on my valuation model I uploaded last week. I\’m eagerly waiting for your reply. Any comments?

Sorry, I forgot to inform you that I dont have permission to access that file. Maybe you can reshare, i\’ll check when possible. Thanks.

Hello Mr Karthik,

Your clear explanations in the Integrated Financial module were very helpful. However, I noticed a difference in the DCF model presented there in Fundamental Analysis compared to the one in Integrated Financial Modelling.

Could you clarify the reasons behind these differing approaches and which model is generally more reliable? Understanding this would solidify my grasp of DCF modeling.

Thanks in advance

Varun (Bengaluru)

Both are similar Varun, I\’d suggest you consider the method in Financial modelling 🙂

I tried 2 times to post the valuation link. After I click \’post comment\’, the comment vanished. Maybe the system took it for a spam since it had 2 links?

Yes, comments with links are for moderation. I deleted one of you comments and approved the other. Will check as and when possible.

Thanks for considering. This is the valuation model I did for Vinati Organics with latest data from Q2FY24. Also please refer to the second link for the explanation on the valuation projection, in case the model is not clear.

Valuation model link👇

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1KkQgzRTxDMWoXvQNPlgZ-YR7NQwWz5ro/view?usp=drive_link

Explanation link for the model(In case it is not clear)👇

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Q6dLRnXDVrBo2JLrf1Pw8ddAKDo4HzqP/view?usp=drive_link

(If you feel that this is a bad projection, please feel free to comment Sir. It would help me to learn better)

Hi Karthik, thanks again for providing these materials which are truly amazing!

Question –

After getting done with the \”science\” part which is building a comprehensive model, what all should one read to cover the \”art\” part. Like you mentioned, this is what would separate different models, so how should we ensure that the assumptions and growth rates we take in our model is based on good research and best incapsulates the future? What all should we read/know to make good judgements here?

Its the annual report that you need to be reading, Phil. The art part gets better as and when you start understanding the business better.

1. Professor Aswath has uploaded his equity risk premium data for countries in his website. For India, this comes to 7.81% of equity risk premium, and 3.21% of country risk premium, which adds up to a total risk premium of 11.02%. That is huge and my result will hardly show undervalued readings if I calculate with huge risk premiums. Any solutions Sir?

2. I have worked in the past 1 month to value many companies using your teachings and Professor Aswath\’s model. I would like to show one of my valuation models to you if possible.(Its just a single screenshot) I will be happy if you could see and comment on it😊. Is there some place where I can sent it?

(Its just a single screenshot. But if you are caught up with work, I totally understand. Thanks)

1) That sounds fairly aggressive, but that its Prof.Damodaran, so it must make sense 🙂 No solution as such, unless you want to specifically lower the risk premium.

2) Can you upload the sheet on Google drive and share the link? I\’ll see if i can go through it. Thanks.

This content really helped. Thanks a ton!

Happy learning, Sanket!

Enjoyed reading and working with my excel through each chapter. I had many doubts about building a Cash flow statement, equity section of the balance sheet and CAPEX, which were clarified by this. Many many thanks for keeping the reader attracted throughout the module.

Happy learning, Sai!

Thanks for the reply sir. Finally after some modification, I found out that if I calculate the terminal value using a seperate WACC with a small risk premium,the model works out fine. I did this because I\’m assuming that we only expect smaller returns during a stable growth premium. Moreover I did try to replicate some of Mr.Aswath\’s model and found that he also uses a seperate WACC for stable growth calculation. Also if we look at his last Zomato valuation model, even that had a seperate WACC for stable growth. I tried doing this for both your teachings in DCF model in fundamental analysis module and this integrated module, and both showed similar and good results.

Since I\’m doing all this on my own, I dont want to overassume things and do this in a wrong way. And so as always your opinion means a lot to me and will provide value. So is it fine if I use a seperate WACC for terminal growth calculation keeping a 2% risk premium above risk free rate?

Absoultely, Sathish. That should work either. I\’ve not seen the Zomato valuation but since its coming from Mr Damodaran, I\’m fairly certain its the best out there 🙂

I do have a couple of questions Sir.

1.In Mr.Aswath Damodar\’s book, sometimes, the terms \’stable growth rate\’ and \’terminal value growth rate\’ are used interchangeably. Can I take it that both are same?

2. If that is the case, his argument is that the stable growth of a company can never be greater than the economy\’s growth and so the simplest way to set a stable growth rate is a risk free rate. Here I\’m trying to value Deepak Nitrite. Only if I keep the terminal value growth rate to around 6-7% is my intrinsic price output reasonable enough to somewhere around current market price. Is this fine, or should I taper it down?

Thanks.

1) Yes. Essentially, the terminal value growth rate is considered stable and factored nearly at the long term inflation value of the country.

2) Not the economy;s growth, but the inflation value. You can try to taper it down a notch below.

FCFF calculation formula had deferred tax added to it, but I couldn\’t find deferred tax added to FCFF calculation in this particular screenshot of share price calculation. I guess you have mentioned about this somewhere but couldn\’t find it. Is it because WACC has been factored for the tax rate and so we shouldn\’t add it?

Thanks

Yes, we take the effect of tax separately. I must have explained the concept of tax shield separately I suppose.

Hi Karthik,

How did you assume the following:

1. Debt-equity ratio of 50%?

2. Expected market returns of 15%?

3. Cost of debt of 10%?

What are the reasoning which goes behind the above assumptions?

Like you mentioned, terminal growth rate is taken as long term inflation rate for a mature business/market. Can it be higher for a growing/new industry?

Hi Phil,

1) Thats the target Debt to Equity for most companies, hence that assumption. YOu can watch the management interviews to get a sense of what ratio they like to maintain.

2) YOu can model this based on historical returns and expected

3) Based on finance charges.

Such a nice feeling!Finally reached the final output:The Share price of the company.The journey was very interesting all the way.Not to mention that Your writing skill is outstandingly well.I find all the writing very easy to understand thus keeping me on the track while learning.I thank you from the bottom of my heart.Grateful.I want you to provide us the Advance Level of this modelling system if possible in the coming future.It will also be an enjoyable learing to me as always.

Thanks for the kind words, and I\’m so glad that you could do the complete modelling. Happy learning, Ujjal 🙂

How to use dcf method for banks as they generate a negative cash flow ?

Hi Karthik,

I can also sense now that to make a last DCF model the values and the calculations we did to derive FCFF doesn\’t required data from sheets from Assumptions sheet, and schedule sheet… So can I assume that these sheets are also required but has different objective like Asset schedule sheet is giving me assets projections and so on…

Secondly, how you come up with 10^7 while calculating no. of shares in a company ?

Yes, Abhishek, each sheet has a different purpose in the entire module.

10^7 = 1 Crore.

So, that target debt : Capital ratio 50% is nothing but a weight … and that is equal for both 50% ….

Yeah, thats right.

can we take last 5 years ebit to calculate the FCFF?

Yes, you can.

Hi Karthik,

Under WACC I didn\’t get why you have taken D8*(1-D11) in this why 1-D11 ? I get the debt part which is effective cost of debt but in equity what\’s the weight of equity ?

Thanks 🙂

Debt + Equity = 1

So 1-debt = Equity.

Hi Karthik!

What about a company who is in development phase and neither has started any commercialisation of products yet (Just incorporated) ? Has just done with product R&D and entering the market to raise funds ?

Will the same DCF model works ? Or it\’s not suitable for such companies ?

Please tell

DCF works, as long as there is positive cashflow, otherwise you will have to look at other things like relative valuation techniques.

Hi Karthik!

I have been reading Varsity since I was in 6th grade (2016). You and Nithin are the reason I got this knack for finance and the markets. Today I have cleared my CA Intermediate exams and got accepted to EY in the Valuations Domain, in which they accepted only 8 candidates in the whole of Mumbai.

I used to ask questions on the same page where now I am writing this. Karthik you are a genius. The way of teaching these concepts is so ingenious. I mean a 14 year old boy learning Fundamental Anaylsis and being able to read the whole Annual Report and able to draw conclusions is just because of you.

Again Thank you so much Karthik for these wonderfull modules! Wishing you the best!

Ram Agrawal

https://www.linkedin.com/in/ramagrawal19/

Thanks for letting us know, Ram. Super happy to know that you;ve joined EY and happy to note Varsity has played a small role in your journey. I wish you progress more. Good luck 🙂

Sir, I have no financial background. If you tell us, the company you used to build this model, I will understand the terms tracing them with the figures. Kindly understand that Fundamental Analysis was easier to learn because you mentioned the company. Because of difference in the terms among companies, when you don\’t know the company in the main model, nothing is useful to learn.

This is a dummy compnay 🙂

Sir, now that we have completed this module’s (?) chapters, could you please tell us which company you used for main model?

Let that be an unknown 🙂

Loving very much the study with varsity

This module is still not available on app, When this will be available on app and certificate for that

We will put it up soon, Gaurav.

5th Year cash flow * (1+terminal growth rate)/(WACC-terminal growth rate)

Sir in this terminal growth value formula, it says 5th year cash flow, but the formula in the excel illustration takes 10th year into account, which is represented by the cell N11. I\’m a bit confused here. Could you clarify? Thank you.

Its from the 5th year to 10th year onwards, so 5 years in all 🙂

Sir,

Why here not given a pdf format material ?

Will update soon, Rahil.

Dear Sir,

Varsity is one of theeee best I have come across with such high precision…

Requesting you please upload PDF for Discounted Cash Flow Analysis (DCF)

We will do that in a day or two, Mohiuddin.

Hi Kartik Sir,

First of all thankyou for sharing insightful content that you have shared on financial modelling if possible can you kindly make more content on advance financial modelling as it would provide great help for further learning.

Sure Vishal, will try and do this.

pls provide pdf for this module

Hi Karthik,

I have already learned the Fundamental analysis module in which the buying price of a company was calculated and none of the items in the p/L and balance statements were projected.Can you please tell if it is enough if I select a company with those learnt in Fundamental analysis module?

Also,all the Integrated Financial Mdelling modules are bit complex and requires long hours of learning.It would be very helpful if the pdfs are shared soon Karthik.

YEs, just basic FA itself is good enough. This is for people who want to make extra effort to figure out valuations. PDF, yes, I will try and put that up.

heartfelt Gratitude

I completed my model building and was completely satisfied with the result.

Happy learning 🙂

the chapters on valuations are verbose and explained meticulously. A big thank you for the same.

I couldn\’t find the link to the excel sheet. Could you please help

thanks

Thanks, Rishika; glad you like the content. The download link is right above Key takeaways section 🙂

Why is this course not available on mobile app? :\’) I would have added its certificate to my previously earned varsity certifications.

We still need to upload it, Kapil.

Hi sir,

Can you please make a module like fundamental analysis of how to analyse banking industry balance sheets.

Thats been on the cards for a long time, will try and do something about this.

Hello sir, could you recommend a few companies with relatively simple financial statements that I could start analysing? It\’ll be really helpful.

Look for business which are not complex. Ideally they should have one of two products. Something like Hawkins, Bata, or maybe Exide batteries. These companies are good to learn the concepts from.

hi sir,

if possible kindly provide the download pdf option like provided in some above modules.

I am a non financial background person and i have read your fundamental analysis module which was so easy to understand thanks to you.

Thanks ad regards.

Sir, new modules are available on app or not like there are I think 11 modules on Varsity app and on page there are 13 , so other two whene will be available on it?

This is not available yet.

Sir please can you upload the PDF of INTEGRATED FINANCIAL MODELLING MODULE🙏🏻🙏🏻

We will some time for that, Muthu.

Hi Sir,

I could not find the pdf of the module. could you please upload it?

Hi Sir,

I could not find pdf for model here. could you please upload it?

We are yet to prepare the PDF.

Name of the company in the main model

There is no name 🙂

Karthik sir, is all varsity modules are completed (or) can we expect further new modules in varsity

I\’m not sure for now, Muthu. Currently focusing on adding video content.

Hi karthik

Can you give pdf link of this pls

Will try and put this up soon.

Sir I am recently see this module and want to comment for uploading PDF for this module. But after seeing these comments from 2022, have no hope for the PDF now. Really surprising and also disappointing as I have a very good and genuine image of Zerodha. Hope you serve better without giving false assurance like this. Thanks and looking forward your response.

Pradeep, we had uploaded a PDF, but had to delete it as few chapters got updated. But thats a slip, we will do this soon.

I am pretty much interested on the education course you publish in YouTube and i request you for the financial modeling video to be published on YouTube as i am keen interested to watch.

Also I like to thank Varsity team for educating us.

Thank you

Thanks, Mayura. I\’m glad you liked the videos on youtube as well. I\’ll try and put up some content around FM.

Sir kindly please make a pdf version available for download

I will do, Leo. Give us some time, please.

Kartik sir, when will Hindi edition published?

Hi Sir,

What\’s difference between DCF calculated in Module 3 (Fundamental Analysis) vs Module 13 (Integrated Financial Modeling). Kindly advice which one to follow. I\’m looking to calculate valuation of a stock price.

Its the same; this one is more detailed.

Current DCF Model is bit complex than the DCF model introduced 4years ago. Luckily have pdf copy of FA statting earlier model and maintaining excel sheet with different co\’s, also created new DCF model on multiple co\’s.

Ex- Old DCF for \”PUDMJEEPAPR\” Co is showing intrisic value =Rs. 60.

Current DCF model showing intrinsic value=Rs. 29 ,while today\’s CMP=Rs.44

It would be helpful if you can compare two models (old&new) to understand merits & demerits of both models.

Thanks!!!

They both are similar, Abhi. This version is elaborate and in greater detail.

Hi Rangappa Sir , Finally today skimmed this module also , like always great work

Can you please upload a pdf link for this whole integrated Financial Modelling module also , because it is easy and more interacting when we have a physical copy in hand .

Thnx again for your valuable and everlasting content on varsity

Thanks, Vaibhav. Glad you liked it. We will work on the PDFs soon.

Sir, first of all I\’m very grateful to you for this module. Your writing skills….I\’m now fan of it. What you can teach through your writing, can\’t be learned from videos. I enjoyed a lot. Thank You, Sir!

One thing I needed to ask, whether this is enough to learn Financial Modeling or I need something more. And if I need extra learnings, please guide me for that. I\’ll be highly grateful to you, Sir!

Thank You.

Thanks for the kind words, Mohammed. The model that we have discussed here is a basic model, which serves as a good starting point.

I was reading up Damodaran Sir\’s book too simultaneously. A couple of consolidated queries from your work and his book. The main issue is not all annual reports use similar terms. They might be a little basic so please bear with me:

Q1. What is book value of debt? Does this just imply total liabilities in the balance sheet?

Q2. In the book, they talk about (Principal repaid- New Debt issued) while calculating FCFE. Will this be equal to interest charges in your equation? Also if I were to be locating this in our balance sheets, does it go by any synonym?

1) Book value of debt is the total value of debt in the books. You can even divide this with total outstanding shares to get a sense of debt per share :). Of course, not a standard ratio this one.

2) Principal repaid – new debt issued is simply the outstanding debt on books.

Btw, which book are you reading?

In Section 18.3, we are calculating FCFF ad EBIT. I understood calculation, but want to know are we calculating FCFF & EBIT from past values and for how many year??

For Ex- Calculating FCFF and EBIT for \”infosys\”, So we are calculating FCFF & EBIT values from past 5 years and adding it in 6 years onwards as per pic in section 18.4? Becuase we don\’t have EBIT & FCFF values for next 5 years.

Also, I didn\’t find excel sheet.

Thank you so much for educating!!!

Yes, you can calculate the EBIT historically and extrapolate to the future years. Adding the excel, forgot to link it 🙂

Excel sheet link not working

Ah, I think I forgot to upload. Please check in a bit.