Remembering Danny

The legendary Daniel Kahneman passed away yesterday at the ripe old age of 90. There aren’t a lot of people you can look up to in the world of finance, but he was a rare exception. I consider him one of my heroes.

He and Amos Tversky, his long-time collaborator, were true renegades who humanized the abstract and dreary world of finance. He won the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for showing that we humans don’t always make the best decisions in our self-interest. Until then, economists and finance guys wrote elegant and fancy theories with the assumption that humans are rational creatures who act in their best interest.

His work on human judgment and decision-making kicked off the behavioral revolution in economics and finance and upended conventional wisdom. His work was akin to taking a knife and tearing the fabric of reality; it showed us all that the worlds of finance and economics were stuck in a Truman Show-like simulation. The weird thing is that he was neither an economist nor a finance guy, but his work fundamentally reshaped both worlds.

I owe a debt of gratitude to Danny, as people fondly called him, because he’s shaped my worldview about finance profoundly. When I joined Zerodha about 7 years ago, I knew jackshit about finance apart from the fact that a thing called the stock market existed. This was a totally different world in which “stocks” were still stocks and not “stonks.”

As I started learning about the markets, I soon had a “yeno maga idu” moment. It’s a Kannada phrase that loosely translates to “What is this, bro?” The reason I had the moment was because the more I learned the basics of markets, the more I saw some of the smartest people do phenomenally dumb things. I couldn’t wrap my head around this. As I learned more, I stumbled onto the subversive and delightful world of behavioral finance, and my worldview of finance was turned upside down.

I have been thinking about what to write since yesterday night when a colleague shared the news that he had passed away. There will be countless well-deserved obituaries and summaries of his work, and I don’t have much to add. Then it hit me: There are two things that I always associate with Daniel Kahneman.

The first is a story from his childhood:

In one experience I remember vividly, there was a rich range of shades. It must have been late 1941 or early 1942. Jews were required to wear the Star of David and to obey a 6 p.m. curfew. I had gone to play with a Christian friend and had stayed too late. I turned my brown sweater inside out to walk the few blocks home. As I was walking down an empty street, I saw a German soldier approaching. He was wearing the black uniform that I had been told to fear more than others – the one worn by specially recruited SS soldiers.

As I came closer to him, trying to walk fast, I noticed that he was looking at me intently. Then he beckoned me over, picked me up, and hugged me. I was terrified that he would notice the star inside my sweater. He was speaking to me with great emotion, in German. When he put me down, he opened his wallet, showed me a picture of a boy, and gave me some money. I went home more certain than ever that my mother was right: people were endlessly complicated and interesting.

It’s a powerful story that captures in vivid detail the paradox of human nature: the same person can commit unspeakable acts of evil, yet also display extraordinary kindness. He brought this fundamental understanding of the complexity of humanity to everything he did.

The second is this brilliant quote:

Nothing in life is as important as you think it is, while you are thinking about it.

I always think about it whenever markets fall and people lose their minds.

I have a confession to make: I haven’t read Thinking, Fast and Slow. One shouldn’t speak ill of the dead, but that book is like Stephen Hawking’s’ A Brief History of Time. Everybody has it. Nobody has actually read it. Sorry Danny. Thinking fast and slow has been lying on my bookshelf like an unloved child, waiting for the slightest scrap of affection. There is much I’ve learnt from listening to his podcasts and reading his papers, but his book has only ever helped me fight my insomnia.

Despite its promise, the field of behavioral economics that Daniel Kahneman helped create has lost some of its sheen. Behavioral economics, like many of the social sciences, has been engulfed in a replication crisis. Researchers have been unable to reproduce the findings of many famous studies, including several of Kahneman’s own.

To make things worse, the field has seen several scandals due to outright fraud. All this has led critics to paint the entire field with a broad brush, calling behavioral economics a “pseudoscience.” Several people I admire talk about people like Richard Thaler and Daniel Kahneman in a disparaging tone. This is unfair, no matter their convictions. The true mark of humility is to treat even those you disagree with, with the utmost respect.

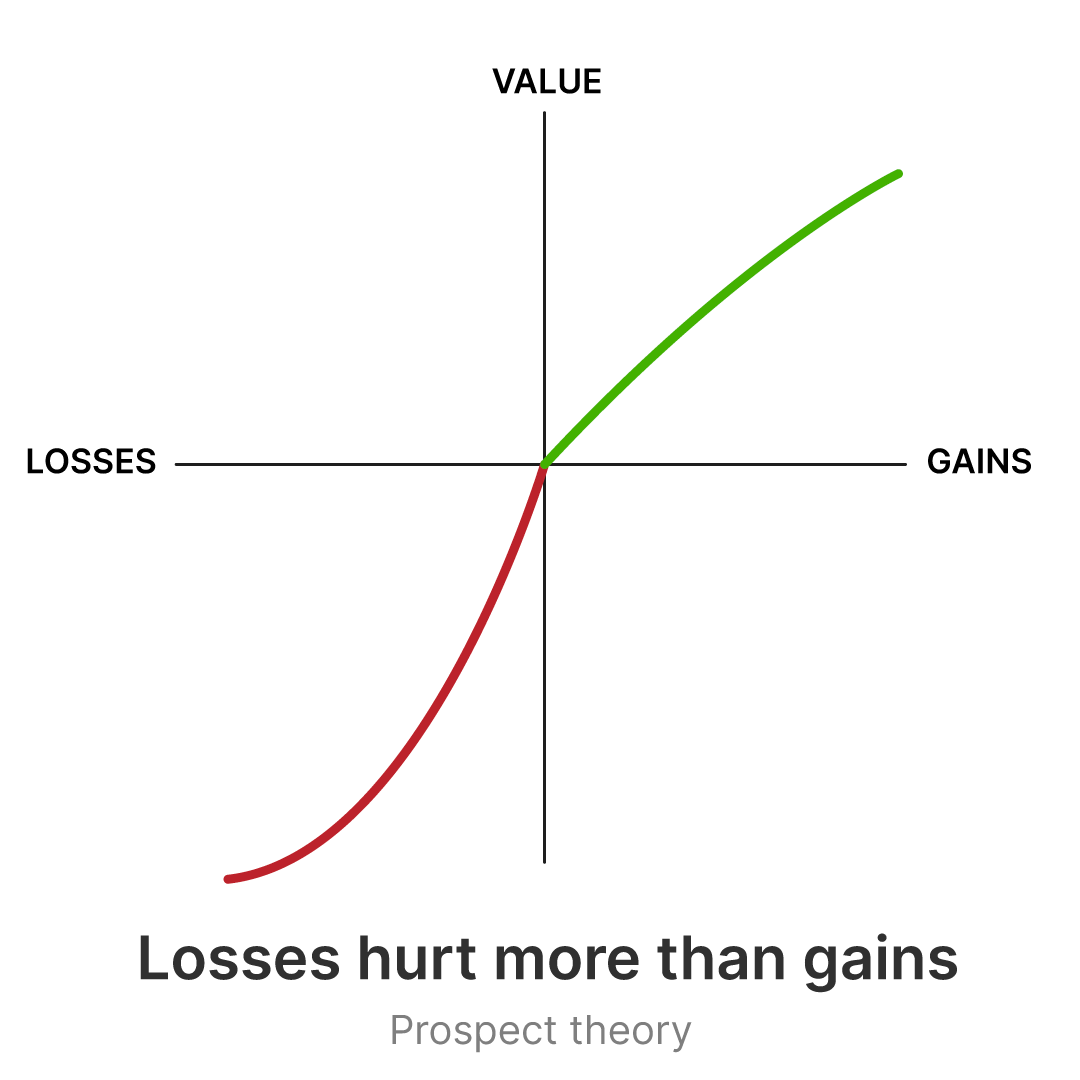

Despite all its problems, there are a lot of efforts to fix the issues that plague the field. Moreover, the replication crisis has been a blessing because it’s clearing away the underbrush. It’s not like everything in behavioral economics and finance is useless. Several of its foundational insights, like Daniel Kahneman’s prospect theory – including its observations on loss aversion – have stood the test of time.

The true measure of a man

If you measure a person’s worth by the amount of good they’ve done for others, Daniel Kahneman is right up there with the likes of Jack Bogle. To me, his greatest legacy is forcing financial services to put humans before finance. Every sensible financial advisor today tailors advice based on a person’s behavior, and investors are more familiar with their own shortcomings. That’s all thanks to Daniel Kahneman. If one were to quantify the benefits of this shift, it would be in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

It’s become fashionable to say that all “behavioral finance” is useless, but there are real-world examples that show otherwise. The field has also come a long way. There are now spirited debates inside the behavioral sciences about whether people are “biased” and “irrational” or if “deviations from rationality” can be explained by the evolutionary sciences. Personally, I am not a big fan of terms like “bias” and “irrational.” I even wrote about them recently.

There’s also a great deal of self-reflection about the lack of real-world applications and cohesive behavioral frameworks. That introspection is a sign that the field is on a good path. This has tangible benefits in the real world. Behavioral applications have become part of the policy toolboxes of governments and companies around the world. All of this is due to the behavioral revolution that Danny Kahneman unleashed.

Thank you, Mr. Kahneman, for making finance more humane. I will miss listening to your wisdom.

Another favorite quote of mine:

The idea that the future is unpredictable is undermined everyday by the ease with which the past is explained.

A few recommendations

Daniel Kahneman’s Nobel Prize lecture

A few good podcasts

https://open.spotify.com/episode/5JWPuUrAKxWY1DvVJBIZaw?si=IVxndVBzT4O4RklPlYlVMA

Let me congratulate you firstly in recognizing value in this man’s works and ideas. Not many people do. He was a man of another era. The great Jewish american and European intellectuals of the 20th century. I have been following him and his ideas on edge.com for many years now. I do have a brokerage account on zeodha and I admire its founder Kamath. Its refreshing to see so many good connections.

Agree Madhu, he’s a true giant. Edge is one of my favorite websites. It’s a goldmine.

You mean Edge.org right ?

Hey Bhuvan!

Great article! I have also not read Thinking fast and slow. But would like to know in which part of industry do people say it is useless. I follow behavioral scientist, one community I am aware about.

Thanks, Mihir. It’s mostly people from finance who have weird things to say about behavioral finance. Behavioral Scientist is a brilliant website. If you wanna keep track of what’s happening in this field, this twitter list is a good place to start.

Its such an honest eulogy! Thank you Danny for your time, wisdom and knowledge.

Thank you Bhuvan. You said it so succintly.