Markets and macros | Youth unemployment, falling FDI, rising gold prices and more

We keep reading tons of interesting things, not all of which we share or write about. So, we figured, we’d share short summaries of what we are reading and tracking that you may find interesting.

Bad job

The International Labor Organization released the India Employment Report 2024, and it makes for a depressing read. The report notes that there were some modest improvements in employment numbers between 2000 and 2019, but COVID reversed much of this progress. Overall, despite whatever meager progress, India’s employment conditions are poor. It’s a 150 page report but here are few highlights that stood out to me:

- At a broad level, there has been a shift away from agricultural employment. The share of agriculture in total employment fell from 60% in 2010 to 42% in 2019. The share of construction and services rose from 23% in 2000 to 32% in 2019. Manufacturing employment was flat at 12-14%.

- Employment growth from 2000 to 2019 was stagnant. The increase in employment post-COVID is largely in agriculture. This shift, post-COVID, was due to the lack of employment opportunities.

- Nearly 90% of the workforce is informally employed, which is an indication of poor-quality employment.

- About 62% of unskilled casual agricultural workers and 70% of construction workers across India don’t earn daily wages.

- Rising employee productivity due to technological advancements is contributing more to economic growth than new employment. This is the opposite of what India needs.

- Gig work has emerged as a new form of informal work and has the same drawbacks: no social safety provisions like healthcare, insurance, retirement savings etc.

- India has a decadal window to take advantage of the demographic dividend, with 7-8 million youths entering the labor force every year.

- The quality of youth employment is a problem and can be seen by the fact that the gap between earnings from wage employment and self-employment is small.

- Unemployment rate increased with education level and was highest among graduates, especially women.

- One in three young Indians are not in education, employment or training. The proportion of women with such status, at 48.4%, is disproportionately higher than men at 9.8%.

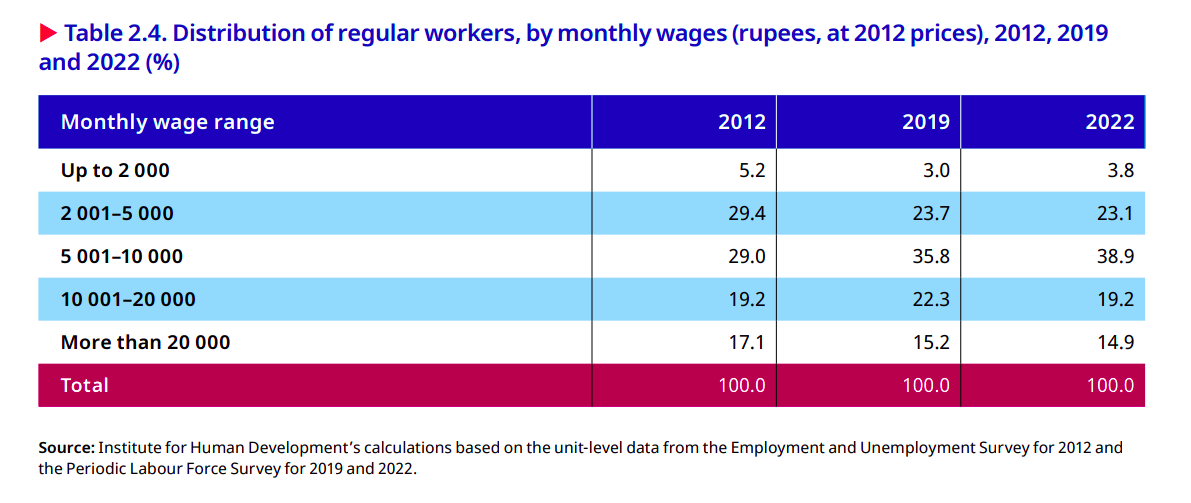

One interesting chart

The Chief Economic Adviser V Anantha Nageswaran made an interesting comment at the report’s release: that the government can’t solve all problems. Oh no!

US exceptionalism?!

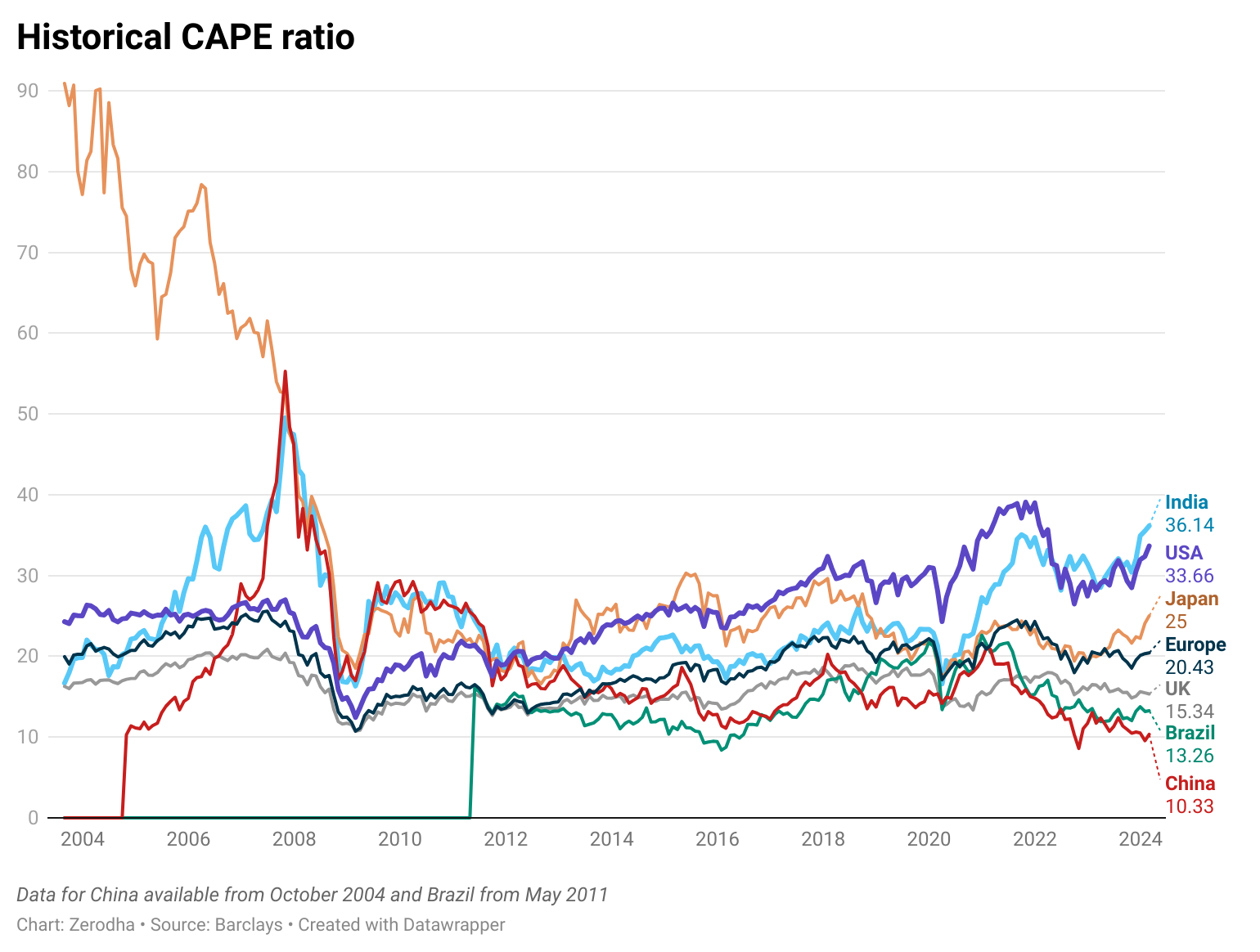

The Economist published an article looking at the puzzle of elevated valuations of US markets. Measured by the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio (CAPE), the US market valuations have never been higher excluding 2022 and the dot-com bubble. The article looks at some potential reasons why investors are paying more for US earnings.

- The US is the home to new-age tech companies while Europe and other markets are dominated by old economy stocks.

- US markets are more dynamic than Europe and emerging markets.

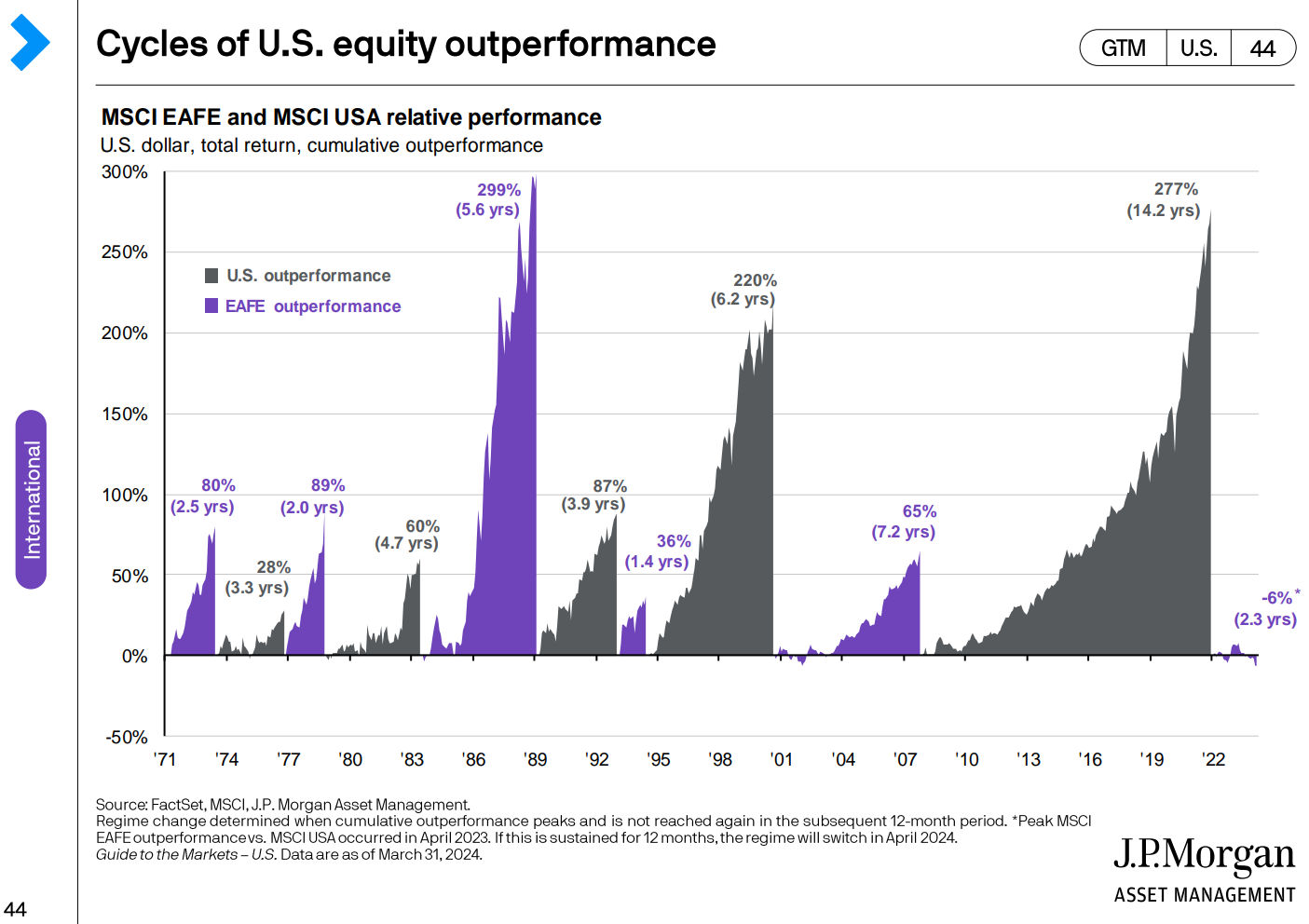

Whether the US markets command a premium is an old debate. Emerging markets have underperformed developed markets since 2010 but they don’t always underperform developed markets – in fact, emerging markets outperformed them from 2001 to 2010.

The post-2010 underperformance was due to several structural and fundamental risk factors, like falling earnings, return on equity etc.

- The CAPE ratio for Indian markets is also at elevated levels. But what does the CAPE ratio tell you? And more importantly, what doesn’t it tell you?

- There’s a strong relationship between the starting CAPE ratio and future returns. A lower CAPE means higher future returns and vice versa.

- The relationship between CAPE and future returns holds in Indian markets as well.

- In the US markets, CAPE has the strongest predictive power over 10 years. That means you can’t use it as a timing tool. In fact, trying to time markets based on CAPE levels is a guaranteed strategy to lose money.

- The relationship between starting CAPE levels and future returns is not ironclad. The strength of the relationship varies across time periods.

- A higher CAPE doesn’t always lead to lower returns but rather a higher likelihood of lower returns.

- At best, CAPE can help you get a sense of the future expected returns and then tweak your asset allocation.

Professors Rajan Raju and Joshy Jacob have published papers in the Indian context.

As an aside, emerging markets are trading at multi-decade discounts relative to developed markets. The valuation gap is so extreme that all the market outlooks from asset managers [1, 2] are predicting low returns for the US and developments and high returns for emerging markets. Alas, the RBI has blocked Indian investors from investing abroad. Sad.

A few more links:

CAPE Fear: Should Investors Be Concerned With Market Valuations?

Why Do US Stocks Outperform EM and EAFE Regions?

Goldman Sachs destroys one of the most persistent myths about stocks

Cognitively dissonant beliefs

I’m a huge fan of AQR Capital because they publish some of the best research on investing. I’m especially a fan of its co-founder, Cliff Assness, who often publishes some amazing perspectives. We often don’t notice it but many of the investment beliefs we hold are contradictory. Cliff recently published a piece on such beliefs and it’s a banger.

The apple of my FDI

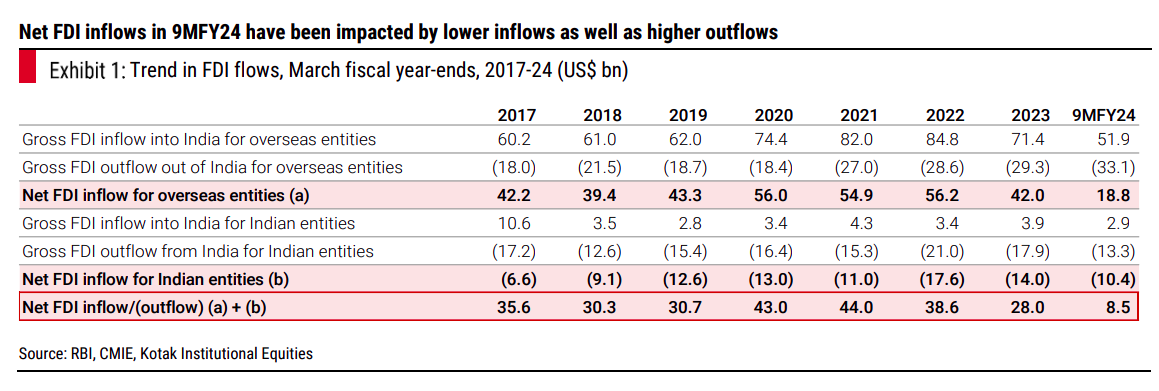

Kotak Institutional Equities published a report with a heartbreaking report titled “India is not yet the +1 in China +1”. Despite all the buzz around the India growth story and the government initiatives and incentive schemes to attract large investments, the money is yet to make its way home.

The short of is that there’s been a sharp drop in inflows and sharp rise in outflows.

What’s happening?

- The fall mirrors global fall in capital flows.

- Judging by the increased IPOs, investors might be cashing out their investments.

- The fall in FDI is across the board, especially in services.

- India’s share of global FDI has fallen from a high of 6.2% in 2020 to 2.2% in 2023.

- China has seen a dramatic fall in FDI while the US, Canada, Brazil, Mexico and Poland have gained.

Also, check out this podcast where Pranjul Bhandari, the Chief India Economist at HSBC Securities discusses why FDI is falling. This podcast showed on my Twitter feed and I haven’t heard it yet. But I had watched an interview of hers in which she had said that it takes time for all the policy initiatives the government had undertaken to attract global capital to start bearing results.

Gold is glittering…finally!

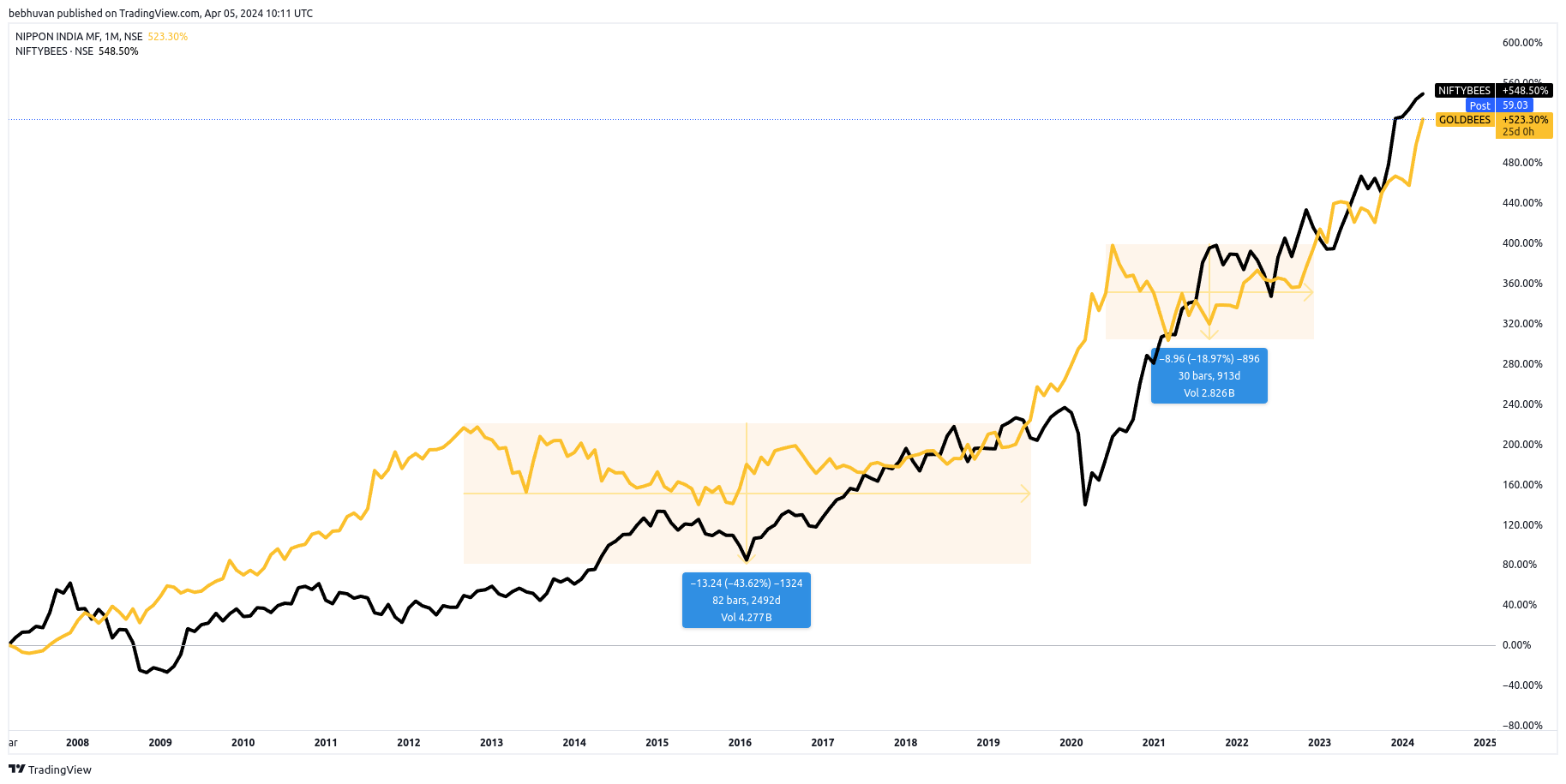

Gold hit a lifetime high. I’ve compared the GoldBeES ETF since inception with NiftyBeES. Both have more or less done the same. Gold is also the most frustrating asset class because it does nothing for years—I’ve highlighted those. For example, it traded sideways from 2012 to 2019.

It’s also a weird asset class because, unlike equities, it has no cash flows. It’s also a controversial asset class because no two people agree whether gold deserves a place in a portfolio.

- Most people think gold is an inflation hedge but it’s an imperfect hedge at best [1, 2].

- Some people argue that gold is as volatile as stocks and there’s no diversification benefit.

- Does it help diversify? Yes, but it reduces returns, as it should. However, Pim van Vliet of Robeco Quantitative Investments suggests that using low-volatility stocks, along with bonds and a modest allocation to gold, allows you to both have your cake and eat it.

This tidbit was prompted by this interesting thread on gold by Jared Dillian.

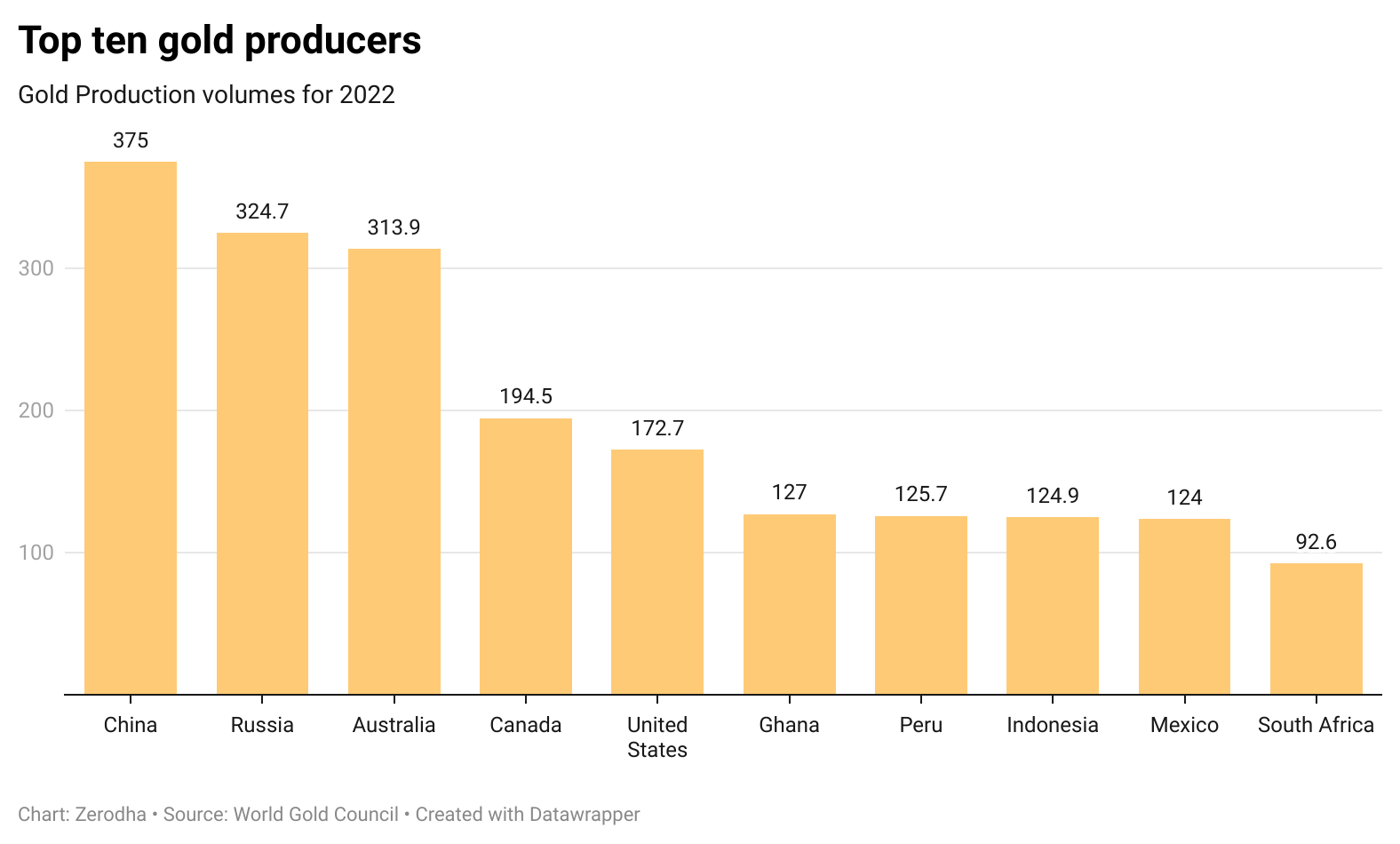

Also, I was curious about the largest producers of gold and what it’s used for. Team anti-democracy is the biggest beneficiary of rising gold prices 😬

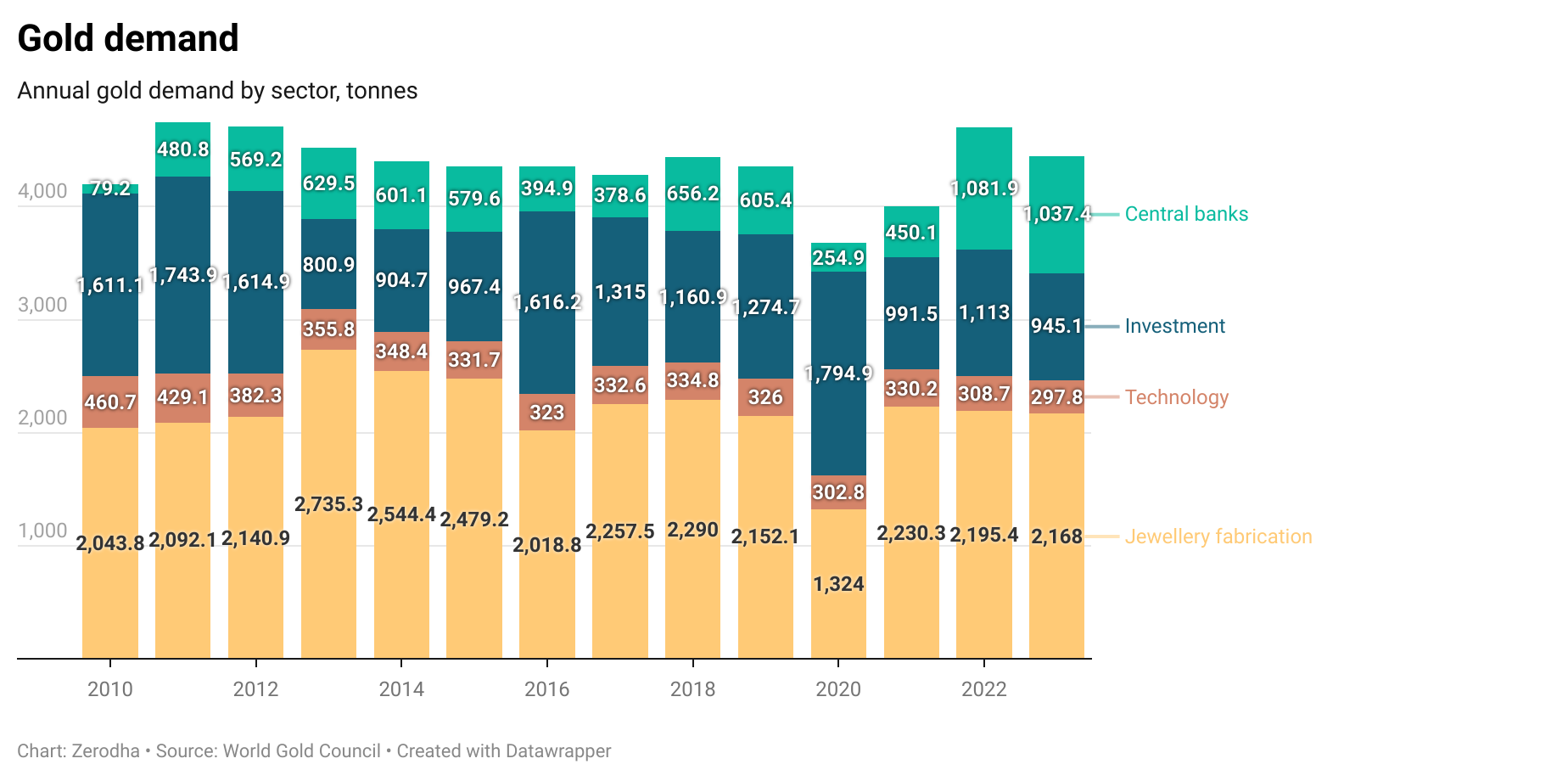

The biggest use case for gold is hoarding. Excluding technology, all the other use cases are in one way or another buying and holding. It’s interesting to note that central banks have increased gold purchases post-COVID.

Hot cocoa 🔥

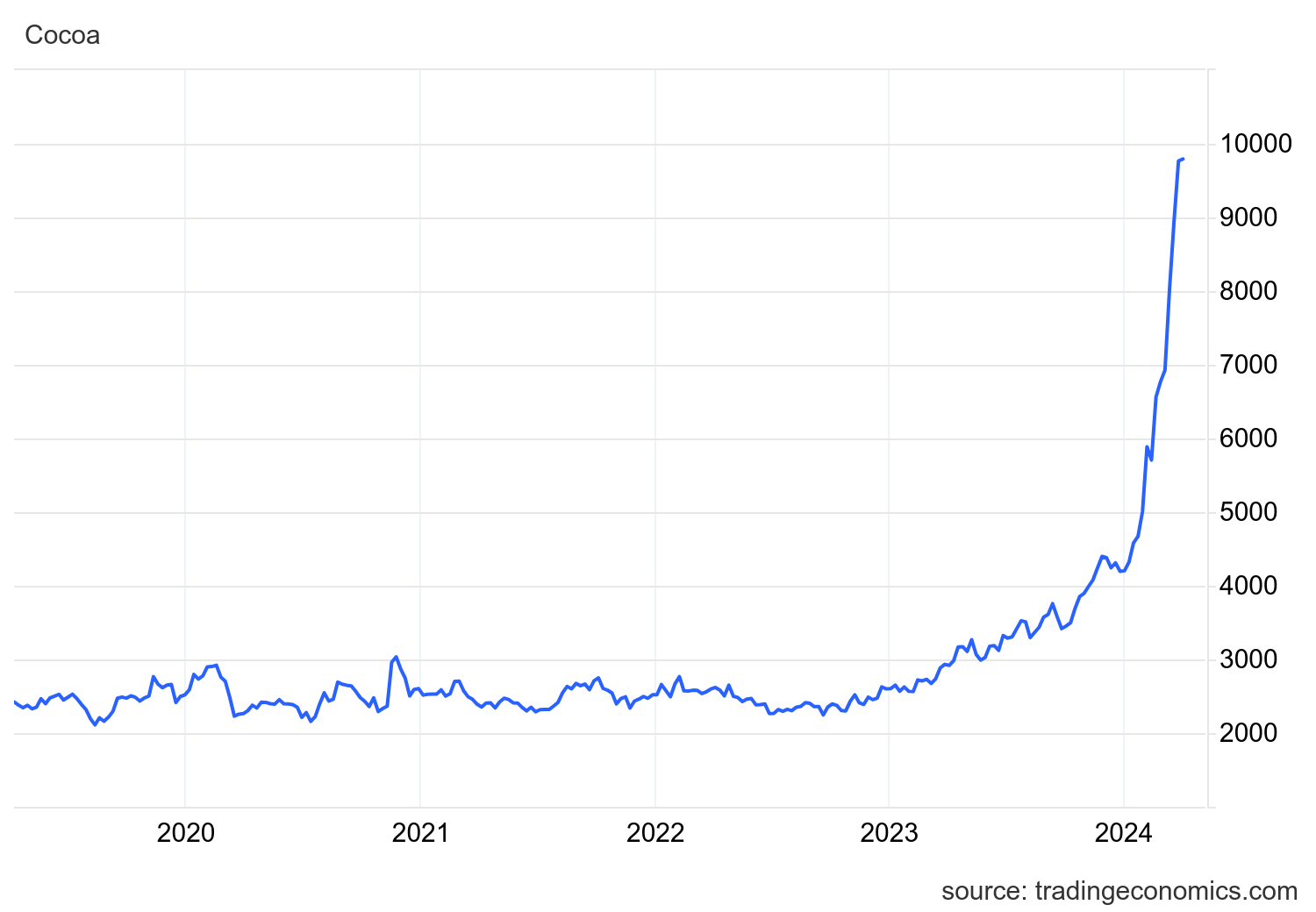

This is not the chart of Bitcoin but Cocoa, the main ingredient in chocolates. Given this dramatic rise in the price of cocoa beans, you will soon have to pay more to satisfy your sweet tooth.

Why are prices rising?

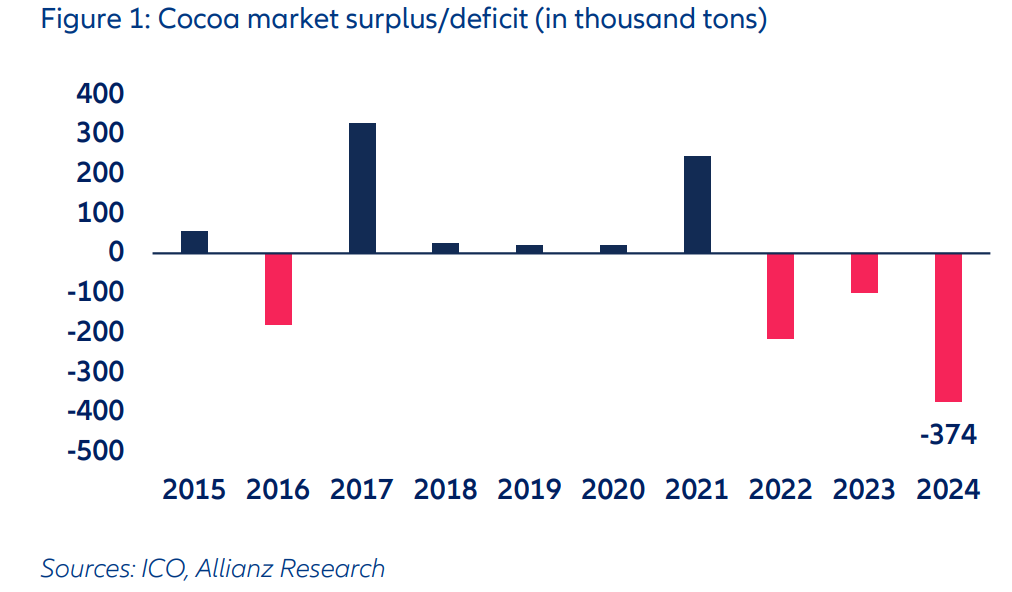

In a previous post, I wrote about how a drought caused by global warming is affecting the Panama Canal, a key route for global shipping. Global warming is the culprit with cocoa as well. Extreme weather conditions are leading to unseasonal rains and scorching heat waves in West Africa, which accounts for 75% of global cocoa production. This is the third year in a row that cocoa production has been in a deficit.

To protect margins, confectioners are likely to explore cost-saving measures such as reducing the cocoa content of their products, substituting cocoa for cheaper alternatives or reducing quantities (i.e. shrinkflation). Alternatively, they may simply increase prices or implement a strategic shift towards premium, high-margin products to counterbalance rising input costs.

AllianzThere are also deep-rooted structural issues at play, including chronic underinvestment in cocoa farms. Today, the crop is still largely cultivated by smallholder farmers, many of whom struggle to make a living income and lack the means to reinvest in their land — which translates to lower yields over time. “Cocoa is a market where the grower produces a very high-value good but receives a very low share of the actual value chain. As a result, replanting rates are very low and cocoa trees are ageing,” said Tracey Allen, an Agricultural Commodities Strategist at J.P. Morgan.

Shashank Mehta, founder of Whole Truth Foods sent an email to his customers announcing a price hike for a few of his products. In the email, he shared a few interesting insights:

- Big chocolate companies haven’t raised prices because “45-50% refined sugar. And barely 15% Cocoa (including derivatives). At best.”

- The big FMCG companies have also locked in cocoa producers with 12-18 month contracts. This means cocoa producers are jacking up cocoa prices to smaller buyers.

Thank you for reading.