A life well lived

One of my pet peeves with personal finance books is that investing gets all the attention. It’s not that investing isn’t an important part of personal finance, but beyond a point, it’s a giant distraction. There are bigger personal finance priorities than investing. Unless you’re an investing professional, spending more than a couple of hours on investments in a year is a waste of time. Watching funny animal videos on YouTube is a better use of the time spent finding the next best fund.

With this apprehension in mind, I started reading Balance: How to Invest and Spend for Happiness, Health, and Wealth by Andrew Hallam, and my apprehensions vanished by the second page. Rather than just focusing on investing, Andrew stresses the importance of having a holistic view of personal finance. This means having good relationships, taking care of our physical and mental health, living sustainably, and finding purpose in life.

Unlike most finance books, it’s an easy read, even if you have no clue about personal finance. By the time I was done reading, I had 11 pages of notes. Andrew shares some beautiful personal anecdotes and also cites tons of research to drive home his points. You might notice some of the studies cited in the book, like the marshmallow test, have come under scrutiny as the field of behavioral science grapples with a replication crisis. But that still doesn’t take away the message or make the book less readable.

Nothing in the book is new; it’s the same advice we would’ve heard from our parents and grandparents, but sometimes we need to hear it differently. What I loved about the book is that there’s no mention of investing until page 83 of a 230-page book. Regardless of whether you’ve already started your personal finance journey or are yet to, you should read this book. I enjoyed reading the book so much that I wanted to share some highlights that resonated with me.

Why?

The book starts with an anecdote about the need to ask ourselves why we’re doing something. This stuck with me because it’s not something we do. For most of mankind’s history, the biggest priority for humans was survival, and our brains evolved for that purpose. For our ancestors, running the moment they heard a rustling in the bush was the difference between surviving till dinner or getting eaten by a lion. We no longer live in such a world, and for the first time in human history, we have the luxury of thinking.

Despite that, most of our choices and actions are on autopilot. We rarely think holistically about our decisions: Why are we studying that course? Why take that job? Why buy that car? Is it because it’s the right thing to do, to show off, or because it makes us happy?

From my experience, when I keep asking, “Why. . . ?” they might start by saying, “It’s just the right thing to do.” But when I ask, “Why is it the right thing to do? Why do you do it?” eventually they say it makes them feel whole, purposeful, or happy. Plenty of people seek success, but they don’t define it holistically.

Asking ourselves such deep questions isn’t easy because such questions can force us to grapple with uncomfortable things, and sticking our heads in the sand is easier.

It’s about more than money

We’re all stuck in a rat race. We’ve lost our sense of self, and our jobs define our identities. Not only that, but we’ve forgotten about the things that matter for things that shouldn’t. The moment we put a rupee value on our definition of success, we’re setting ourselves up for a life of unhappiness. Ntihin had shared this poignant video with the team, and it perfectly captures the hollow lives we lead.

https://youtu.be/e9dZQelULDk

Success doesn’t just mean having a lot of money. I know this sounds like something that belongs in a BS post that goes viral on LinkedIn, but what I’m trying to say is that there’s more to life than just having a lot of money. This is how Andrew describes success in the book:

As I see it, there are four quadrants to a successful life:

- Having enough money

- Maintaining strong relationships

- Maximizing your physical and mental health

- Living with a sense of purpose

He uses the metaphor of a four-legged table. Even if one leg is off balance, the table collapses.

A waterfall of cash can’t cure hemorrhoids or toxic relationships.

Hedonic treadmill

If you have seen the movie Fight Club, then you’ll remember the scene where Brad Pitt, who plays the character of Tyler Durden says one of the most memorable things in modern cinema:

Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy shit we don’t need. We’re the middle children of history, man. No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our Great War’s a spiritual war… our Great Depression is our lives. We’ve all been raised on television to believe that one day we’d all be millionaires, and movie gods, and rock stars. But we won’t. And we’re slowly learning that fact. And we’re very, very pissed off.

It’s so true, isn’t it?

Don’t get me wrong; having good things in life is okay. But if you think that nice things will make you happy, you’re walking down a path of guaranteed misery. We buy the latest cars and gadgets thinking they’ll make us happy, but the moment we get those objects, the joy quickly wears off, and we move on to the next new thing. Research shows that we like the feeling of anticipation more than getting what we want.

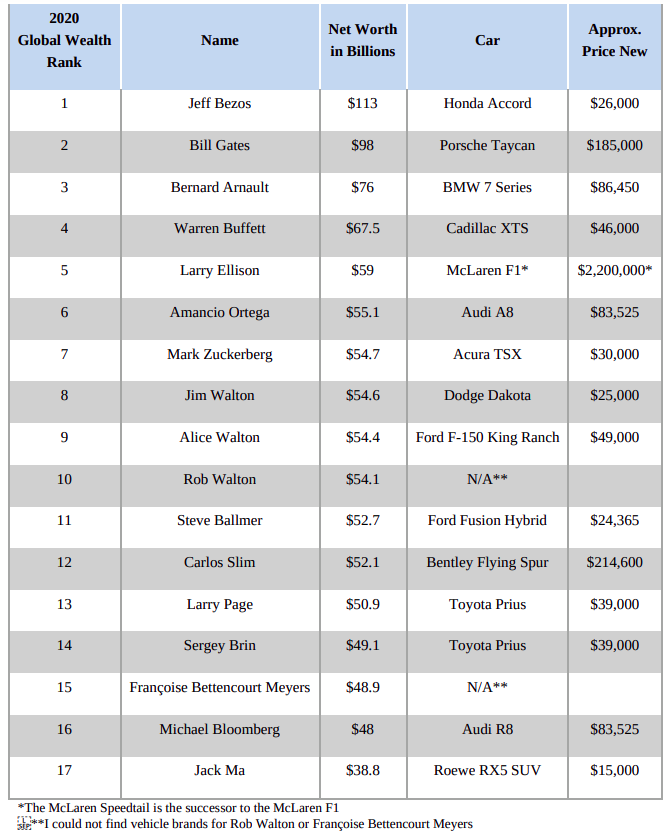

The issue with chasing material possessions is that they can quickly spiral out of control. I was talking to someone who runs a debt relief startup, and he was explaining how young people borrow at exorbitant rates, as high as 40%, to buy the latest gadgets and are unable to pay back the loans. The downside of having expensive things is that they are also expensive to maintain. The book has a nice section about the cars the rich drive. I googled and found that some of these people, like Bill Gates, have fancy car collections. I assume the cars listed here are the cars they drive publicly, but the point remains. Fancy things are nice to own but a pain to maintain, especially when you’re pretending to be rich.

He proposes a simple test whenever you want to buy something:

- If it’s a costly item like a car, would you buy it if no one could see it?

- The next time you’re with friends, will you talk about your experiences or the stuff that you bought?

This doesn’t mean we should never buy anything and live miserable lives. More often than not, the things we buy don’t make us happy. Some things do make us happy. Andrew shares the story of his friend, who couldn’t go cycling with him because of a health issue. He bought an expensive e-bike because it allowed him to enjoy cycling with his friends. Despite the cost, the new bike was worth buying.

Speaking from his experience, he says that spending on experiences makes us much happier, and the research bears this out. So the next time you have to choose between buying a fancy gadget you don’t need and going on a vacation with friends or family, you know what to do.

Think about the people you love or respect.

Now consider whether you would love or respect them less if they didn’t have a car (and weren’t constantly bumming rides). And what if they owned a high-status car? Would you love or respect them more because of what they drove? I hope these questions answer themselves.

We all have our insecurities, and this often manifests in a need to be seen as rich, good-looking, thin, smart, etc. We end up throwing money away to deal with these insecurities. This is why astrology, cosmetics, health supplements, and motivational speaking are billion-dollar industries despite mountains of evidence that they’re useless. Andrew cites a funny yet tragic study to drive home the point. Researchers found that the neighbors of lottery winners are more likely to go bankrupt because they borrow money to upgrade their lifestyles.

Does more money make you happy?

This is a question that has vexed philosophers and people who post threads on Twitter for years. It’s one of those “Is there a god?” types of questions. The closest thing to an answer we had was a couple of famous studies. Nobel laureates Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton, in a famous study, found that money does make people happy, but only until ~ $60,000 (Rs 49.6 lakhs) to ~$90,000 (Rs 74.4 lakhs). After that, it plateaus. Matthew Killingsworth, in another study, found that happiness continues to increase above $75,000. So they both teamed up to test this and published a study earlier this year. They found that Daniel Kahneman was right that happiness didn’t increase beyond a certain level, but that applies only to the 20% of the least happy people. In other words, if you’re already rich and miserable, more money doesn’t help.

You can choose to interpret the studies however you want. To me, they show that the relationship between money and happiness is complicated. The book has wonderful and quirky stories to illustrate the point.

- A fit and happy person who’s been living in his car for the past 27 years yet saves $1100 a month.

- An American who moved to Thailand, living comfortably on social security payments, living a lifestyle he can’t afford in America.

- A nomad family with homeschooled children lives a beautiful life where they travel, save money, and help the community by volunteering.

- A teacher who accepted a 50% pay cut because her new high-paying job kept her away from friends and family.

When they have $500 million, they’re only slightly psychotic,” says Janice. “But once they hit $1 billion, most of them are completely crazy.” She adds, “Many of them lose control of their lives. Their relationships are built on impressing other people with their fancy homes, yachts, airplanes, cars, and collectibles. It’s isolating because they have trouble establishing or maintaining real relationships with people who will love and respect them for who they are as people.

This highlights the relative nature of money. You could make a lot of money and still be miserable because you live in a wealthy neighborhood and have rich friends. You could live in a tiny house and be perfectly content, like most of our grandparents. Letting money influence our actions and choices is a recipe for unhappiness.

This applies to the types of jobs we choose, and Andrew talks about it in the book. The highest-paying jobs aren’t always the best ones. I’m not going to spout nonsense like “follow your passion.” From my experience, I get that we don’t always get to work in places we like and do things we want to. Life can be long, messy, and a nightmare. But you can do other things, like learning, doing, or creating things, that increase the odds of doing something you love.

As an aside, this is also a broader critique of modern society, but we’ve let market-oriented thinking infiltrate all aspects of our lives. We live under the tyranny of “price signals.” We’ve forgotten the value of our community and decency. Our societies today run on cost-benefit analyses, and that’s a tragedy of our time.

This isn’t one of those money means nothing screeds. I understand that money is messy and evokes strong and often toxic emotions. I’ve seen that personally in my life. What I’m trying to say is that you cannot put a number on a life well lived.

Relationships

In a widely shared piece In 2017, Dr. Vivek H. Murthy, the Surgeon General of the United States, wrote:

This may not surprise you. Chances are, you or someone you know has been struggling with loneliness. And that can be a serious problem. Loneliness and weak social connections are associated with a reduction in lifespan similar to that caused by smoking 15 cigarettes a day and even greater than that associated with obesity. But we haven’t focused nearly as much effort on strengthening connections between people as we have on curbing tobacco use or obesity.

In May 2023, he reiterated the importance of social connection in a public health advisory and used the phrase “epidemic of loneliness and isolation.” There’s a ton of research showing a strong link between social connection and overall well-being, but there’s debate about the direction of causality.

In the book, Andrew cites the Harvard Study of Adult Development, which has been studying the factors that contribute to people’s physical and mental well-being. The study began in 1928 with 724 participants and has now grown to include 1330 descendants of the original participants. This is what Robert Waldinger, a psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital, professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, and the director of the study, said in an interview talking about the study:

We started wondering whether we could look back at our participants’ lives in middle age and see what the biggest predictors were of who’s going to be happy and healthy by age 80. We thought that cholesterol level or blood pressure at age 50 would be more important. They were not. It was satisfaction in their relationships, particularly in their marriages, that was the best predictor of a happy and healthy life.

At first, we didn’t believe it; we were wondering how this could be possible. We thought, “It makes sense that if you have happy relationships, you’ll be happier, but how could the quality of your relationships make it more or less likely that you would get coronary artery disease or Type 2 diabetes or arthritis?” We thought maybe this isn’t a real finding, maybe it’s by chance. Then other research groups began to find the same thing. Now it is a very robust finding. It’s very well established that interpersonal connectedness, and the quality of those connections, really impact health, as well as happiness.

When we think of personal finance, the focus tends to be on the “finance” and very little on the “personal.” The book has a beautiful chapter on the importance of investing in good relationships. I use the phrase “invest in relationships” deliberately because it is an investment, and you need to make an effort to nourish them. Over the years, the finance world in the west has woken up to the importance of good relationships. There are increasing studies and a growing number of financial advisors talking about the importance of healthy relationships on life outcomes. Financial planners are stressing its importance as part of their planning process.

You and your stuff

What’s the real-world impact of all the stuff we buy? I don’t know about you, but I didn’t think or care until the last couple of years. I was a proud member of the mindless consumer club. You may be confused right now about why I’m talking about this stuff in an article about a personal finance book. This is what makes this book good. It has an entire chapter in the book on how our mindless consumption habits are destroying our environment. Andrew also gives actionable tips to reduce the environmental impact of our consumption habits. Things like buying local, avoiding single-use plastics, wearing out our clothes and shoes, and resisting the urge to keep buying, etc.

This goes back to my initial point: we rarely think holistically about our actions and choices. While money is in the background of many of our choices, our focus is more on the money than the outcome of spending that money. I say this as a hypocrite who’s trying to be less hypocritical. He mentions this superb video showing how stuff is made and the real-world impact of consuming all that stuff.

https://youtu.be/9GorqroigqM

If you prefer a better version of this, then this George Carlin riff is, in my view, the best critique of mindless consumerism.

https://youtu.be/4x_QkGPCL18

Andrew explains why more doesn’t always mean better lives with beautiful anecdotes and stories. The idea that buying more stuff makes us happy and improves our lives is ingrained in our psyche. This fuels the engine of capitalism; our entire lives are organized around a drive for more stuff, and I say that as a card-carrying member of the club. Kate Soper is a professor of philosophy at London Metropolitan University and the author of Post-Growth Living. Last year, she published a fantastic essay destroying the idea that more is always better, and she illustrates the flawed promise of mindless consumerism better than I can:

The presumption, however, that more sustainable consumption will always involve sacrifice rather than improve well-being needs challenging. Our so-called “good life” is, after all, a major cause of stress and ill health. It is noisy, polluting, and wasteful. Its work routines and commercial priorities have forced people to plan their whole lives around job-seeking and career. Many are condemned to unfulfilling and precarious work lives in the gig economy. Even those with more secure employment will frequently begin their days in traffic jams or suffering other forms of commuter discomfort, and then spend much of the rest of them glued to a screen engaged in mind-numbing tasks. A good part of their productive activity is designed to lock time into the creation of a material culture of fast fashion, continuous home improvement, urban sprawl, speedier production, and built-in obsolescence. Our consumption economy’s markets profit hugely from selling back to us the goods and services we have too little time or space to provide for ourselves.

A life of gratitude

One of the things that stuck with me deeply was the importance of having gratitude. Andrew had a bout with bone cancer, and this is what he had to say when a reporter asked him about it:

This brings me back to the reporter. She said, “Now that you’ve had a life-threatening illness, I suppose it makes you value life more.” I looked straight at the camera and said, “No. It doesn’t matter how high someone’s IQ is supposed to be. If they need their own life-threatening illness to recognize that one day they’re going to die, then that person is an idiot.”

Perhaps the word “idiot” wasn’t fair. Perhaps, if I had tempered my judgment just a bit, I could have shared what I believed to be the most important message: We’re all going to die. Our friends and loved ones are going to die. That’s why we should live with gratitude, being thankful for our lives and the lives of our friends and loved ones. It’s easier to do this when we remind ourselves daily that we’re all here temporarily.

Your life is like a dark hourglass. It gets tipped at birth, and nobody knows how much sand they have left. That’s why we should live with the knowledge that every day is precious. If we’re going to emulate the lifestyles of others, who do we choose to follow, and why?

The research bears this out as well. Being grateful makes us happier, less stressed, and more resilient.

These are just a few things that stuck with me. The book has plenty of actionable advice on how to give forward, save, spend, invest, manage debt, pick careers, and set your kids up for success. This is a wonderful book that I enjoyed reading, and I’m sure you will as well. This book is now my default choice whenever people ask me to recommend books on personal finance and investing.

Very nice information..

Wonderful

GREAT GREAT GREAT ARCTICLE. UNBLIEVABLE EXPERIENCE.

THANK YOU VERY MUCH.

I just loved the article. Too good. The parts about wanting something and later not liking it are very generic. I have read the same pattern from the book ”The Molecule of More” – Dopamine. The sooner we realize this the better it is for us.

Thank you.Worth reading personal finance article. Food for thought.