This week in fintech and health | Edition #1

Once upon a time, I used to publish a fintech newsletter. It was pretty good, if I may be vain enough to say so. Once upon a slightly later time, due to unspeakable and mostly embarrassing reasons, I let the newsletter fall by the wayside. But we’re starting it again. My colleagues have promised to keep this enterprise alive. Every week, we’ll write about the most important stories in fintech and health, which are our focus areas, as well as other developments from the larger startup ecosystem.

It’s been a slow couple of weeks in startupland if you leave aside Paytm and Byjus. Those stories have been done to death, and I have nothing useful to add. A slightly more interesting story was the comments by a Parliamentary Committee on the issue of concentration among UPI apps.

Here’s a quote from a report by the Parliament that Moneycontrol published:

“In this context, the Committee recommends that there should be a focus on the promotion of local Indian players in the fintech universe. Indigenously developed BHIM UPI is a good example of it; however, its share in the UPI market is very low. As India is focusing on ‘Make in India’ in other sectors.”

Why is the government concerned?

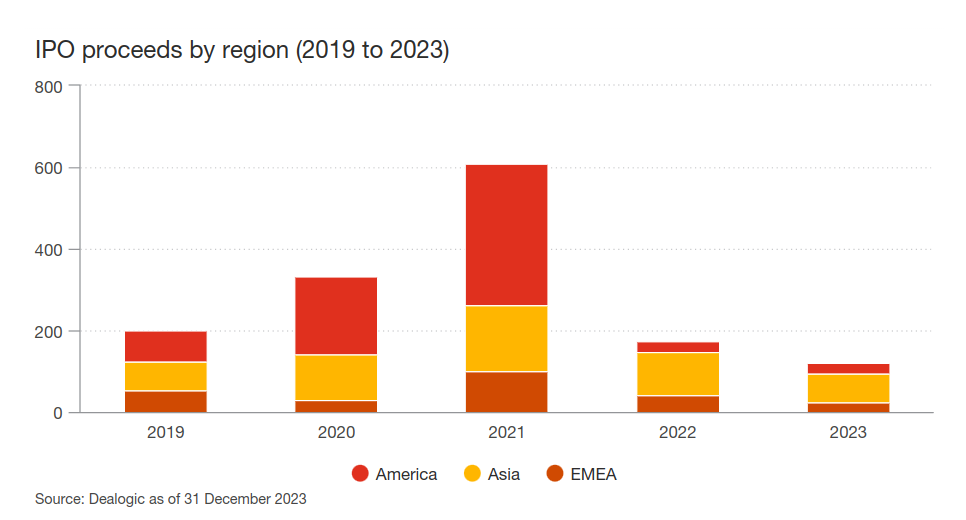

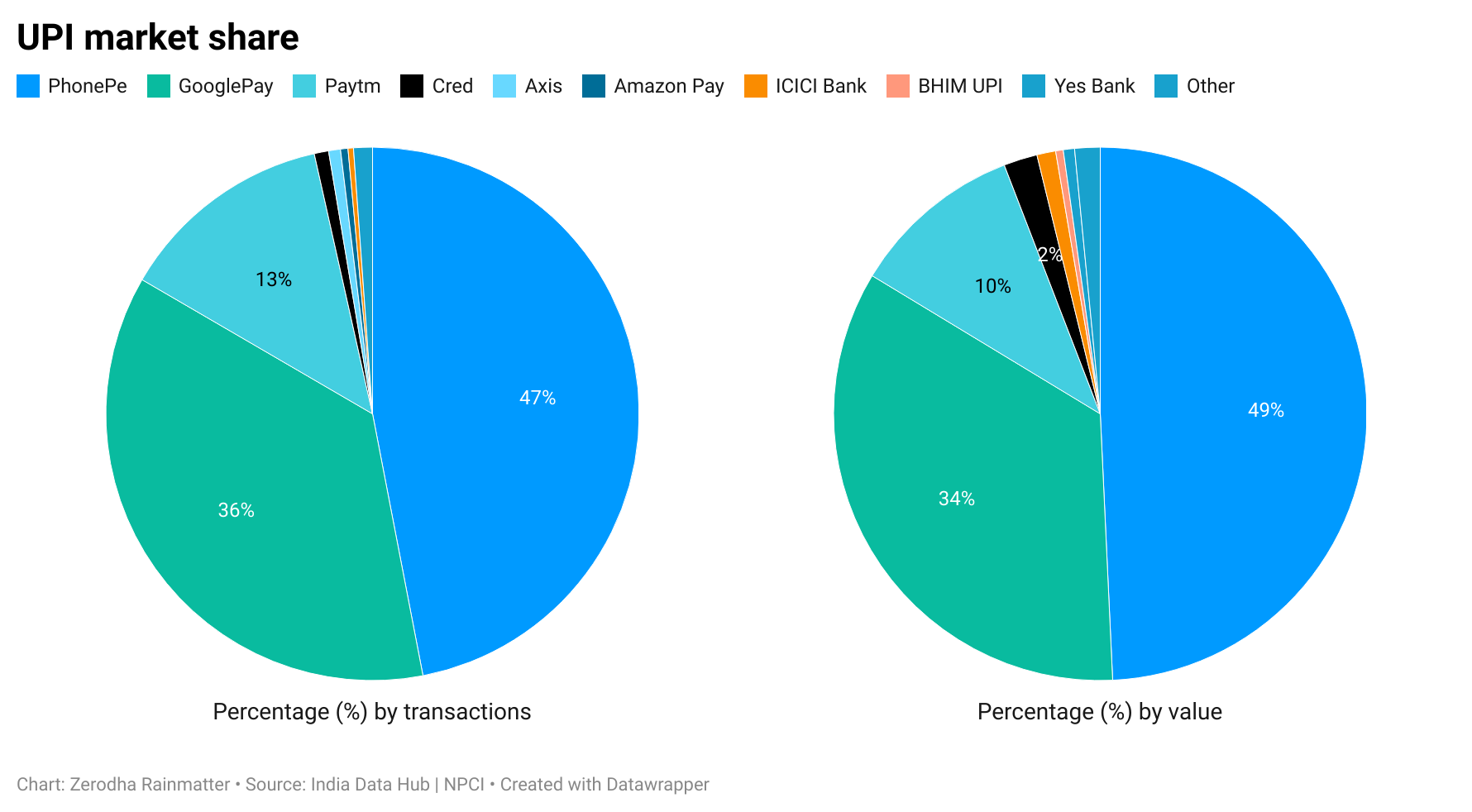

PhonePe and Google Pay account for 83% of all transactions. The majority owner of PhonePe is Walmart, which is a US-based company, and so is Google. The government wants more dominant payment apps that are home-grown.

I don’t care; tell me what it means!

There’s some historical context to the government’s comments. If you remember, in 2020, the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) imposed restrictions on the total volume of UPI transactions processed by a single app at 30%. UPI apps like PhonePe, which have a market share above 30%, had time until 2025 to comply.

When NPCI announced the move to cap market share in 2020, insiders and industry observers were left scratching their heads. How would an app go about complying with the regulation? A hypothetical solution was another app to gain market share, but that hasn’t happened.

Here’s Mohit, our resident payments expert, who always gives you more gyan than you asked for:

Since UPI transactions are free (with zero MDR in payment industry terms), building a standalone UPI app today will also require one to conceptualize revenue channels for the app.

But is there a UPI incentive scheme, right?

The government had announced an incentive scheme of Rs 2,600 crores in FY 2022–23 to be split between Rupay debit cards and small UPI peer-to-merchant transactions. This incentive scheme number might be two-fold for FY 2023–24. However, this is directed at banks acquiring the payments and not to UPI apps. Paytm was able to get a part of this incentive because the Paytm Payments Bank was acquiring all of its UPI transactions. Other UPI apps without a captive bank got nothing.

What about merchants building a better payment experience for their customers?

Many large merchants offer products and services to their customers through their apps. Since they are already generating revenue from their existing products, one may argue that building a UPI experience within their apps would be beneficial to their customers. It is interesting how the value-add that UPI offers—a standardized payment experience across the board—is also one reason a new entity cannot add incremental benefits for their customers, as existing UPI apps have already solved the payment journey quite well.

So, without the possibility of incremental revenue and low prospects of creating incremental value-add, apart from tweaks on the user interface, perhaps the creation of the next big UPI app will need a big landscape change.

So does that mean that starting in 2025, when PhonePe and Google Pay have to comply with the regulation, they will start refusing transactions until other apps become big enough? Only time will tell.

Why is this story interesting?

I’m going to be wildly speculative here. In the past decade or so, large swathes of economies in both developed and developing economies have become concentrated. This has become a political talking point in developed economies, as well as, to a limited extent, in emerging economies as well. There has also been a growing trend in the number of fines and other remedies imposed by competition regulators, most notably in Europe.

The same concerns are also reflected in the actions of financial regulators around the world, who have become increasingly assertive. 2020 was a good example of regulators becoming concerned about competition. In November 2020, Jack Ma, the founder of Alibaba, gave a fiery speech accusing the Chinese government of stifling regulation. The Chinese regulators responded in a brutal fashion by torpedoing the $35 billion IPO of Ant Group and forcing Ma to step aside. In December of the same year, the NPCI imposed a 30% market cap restriction on UPI apps. This was followed by a Chinese crackdown on ed-tech companies and tech companies.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has also been methodically closing regulatory arbitrage opportunities, trying to increase competition in its own way. I see the regulatory restrictions on credit on prepaid, fintech lenders, the shelved plan to offer a new payments license, as well as the move to cap UPI app market share in the same vein. If you look at the regulations from a ten thousand-foot view, you see the same story: the days of a light-touch approach to regulating finance are over.

NoJus

Ok, we’re going to give you just a little bit of Byjus and only the interesting aspects. Dinesh has been following an underappreciated aspect of the story. By now, you would have read the news that the beleaguered edtech giant is looking to raise $200 million through a rights issue at a pre-money valuation of $20 million. This is a stunning drop of 99% from its previous valuation of $22 billion. That means if the existing investors don’t participate in the right issue, they will be diluted. There were news reports that investors wanted to introduce anti-dilution clauses to protect their shareholding. Dinesh explains what these clauses mean.

Startup investments are risky, and investors try to have some clauses to lessen the damage if things go south. If a startup raises funding at a lower valuation than its previous round, it’s called a “down round.” As you can imagine, down rounds are bad for investors because the value of their investments falls. To protect their investment value in case of down rounds, VCs can have anti-dilution clauses in shareholder agreements.

There are two types of anti-dilution provisions: full ratchet and weighted average. Here’s how ChatGPT explains it 😉:

An example of full ratchet

In a startup, an investor initially purchases 1 million shares for $1 per share. When the startup faces difficulties and issues new shares at $0.50 to attract more funds, the Full Ratchet anti-dilution provision kicks in. This provision adjusts the investor’s original share price to $0.50, effectively doubling their shareholding from 1 million to 2 million shares without requiring additional investment. This mechanism ensures the investor’s ownership percentage is protected, despite the company’s lower valuation in the subsequent funding round.

An example of weighted average

In the same scenario, if the company had a weighted average anti-dilution provision instead, the adjustment to the share price would be less severe. Using a formula that takes into account the total number of shares before and after the new issue and the prices at which they were issued, the investor’s share price is adjusted to approximately $0.955. This causes the investor’s share count to rise to around 1,047,120, rather than doubling. This method dilutes the investor’s ownership, but in a more equitable manner, balancing the interests of new and

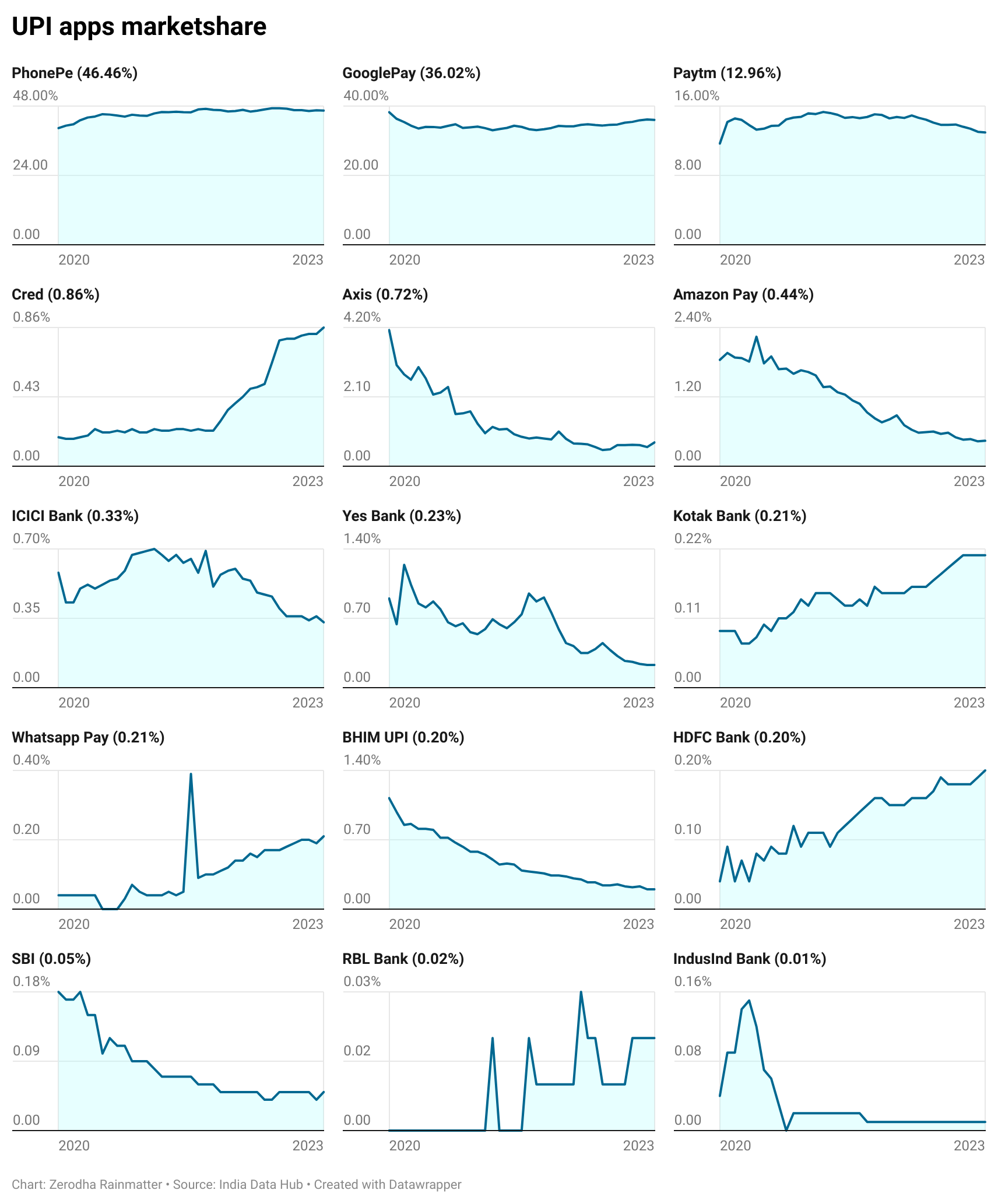

Extended VC winter

VC distributions, or the money they are giving back to their limited partners (LPs), seem to have hit a 14-year low. If LPs don’t get back money, they can’t reinvest, which makes life difficult for some VCs.

Limited partners are disappointed with how much capital is coming back to them from their venture managers. And they’re less inclined to re-up with VCs that haven’t returned much cash. LPs are closely monitoring a metric called distributed to paid-in capital (DPI), which measures how much capital a manager returned relative to what was invested.

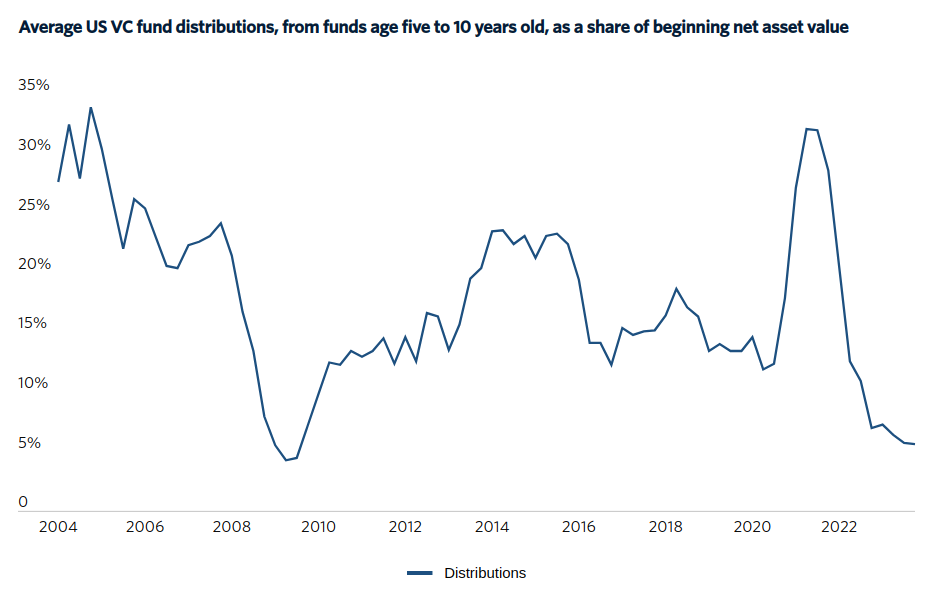

This is because 2023 was a terrible IPO market globally barring India.

Global IPO count — PWC

Trendlines

Finance

With the democratization of AI tools, it’s become easier to create deep fakes. Check out some of these videos that can be generated with simple text instructions with OpenAI’s Sora model. 404 Media published a scary story about an underground marketplace called OnlyFake, where you can buy realistic-looking fake IDs for a few dollars.

These technologies will have profound implications for financial services because deep fakes can bypass the Know Your Client (KYC) process financial firms have in place to verify and onboard clients. Pair this with this tweet from Nithin and his fake AI persona.

SEBI is planning to regulate platforms that sell trading algorithms. — Moneycontrol

The Definitive History of Private Credit. — Wall Street Fintech

Western firms watch China VC opportunity slipping away. — Pitchbook

Sebi wants PE/VC shareholders out of IPO pricing decisions. — Moneycontrol

Here are the fintech startups that could go public in 2024. — Techcrunch

Health

A brutal and damning NYT piece on the hype vs reality of cultivated meat startups. Despite billions flowing in these companies, the reality is light years away from the hype.

A daily “polypill” can reduce blood pressure and cholesterol and reduce deaths due to heart attack and stroke. — Stat News. Pair this with: Exercise is the best medicine for depression.

That’s all for this week. Please let us know your thoughts in the comments.

Hi,

The below piece is incomplete and the example is not well explained. Can you take a shot to explain this better.

An example of weighted average

In the same scenario, if the company had a weighted average anti-dilution provision instead, the adjustment to the share price would be less severe. Using a formula that takes into account the total number of shares before and after the new issue and the prices at which they were issued, the investor’s share price is adjusted to approximately $0.955. This causes the investor’s share count to rise to around 1,047,120, rather than doubling. This method dilutes the investor’s ownership, but in a more equitable manner, balancing the interests of new and

In the graph US Distributions, are u saying that in every year capital has been returned so should i add up the number for every year to measure the return on 100 invested in year 0. What happens if a capital was paid back in year 1-5.

In the IPO proceeds graph, you have used very similar colors for America and EMEA, for someone like me this becomes an issue, can you try and change this for future graphs

Well getting news on my curious topics like fintech & health is something that I am looking forward for more …by any chance

Is there a way I can subscribe to this newsletter so that I can get it in my mail box…

Thank You for putting this together.