What did we learn? (2025)

Another year ends. Time to look back, find lessons to learn, ignore those lessons, and make new mistakes in style.

See, we investors aren’t going to do sensible things. That’s not our style. We’ll keep doing dumb things, and we might as well accept it. But there has to be growth—even when it comes to doing dumb things.

Variety is the essence of life. There’s no point in doing the same dumb thing every year. Aim for effortful, thoughtful, intelligent stupidity over plain stupidity. Be okay looking stupid, but don’t be stupid like everyone else.

So let’s look at what happened this year, do our homework, and prepare to do more unique stupid things next year.

Here are the things that stood out to me this year in the markets.

1. The party’s over?

Since 2020, making money in the stock market was as easy as buying a random basket of stocks. Even spectacular stupidity got rewarded spectacularly. To lose money required a special kind of incompetence—the kind only possible with brain damage.

But the stock market has a way of teaching the same lesson over and over. Things are changing. The one thing I’ve been warning about for four to five years: making money in the markets won’t always be this easy. As valuations climb higher, future expected returns get lower. I never said timing the markets based on valuations is easy, but I’ve been saying this was coming.

This is the second year since COVID where returns were disappointing.

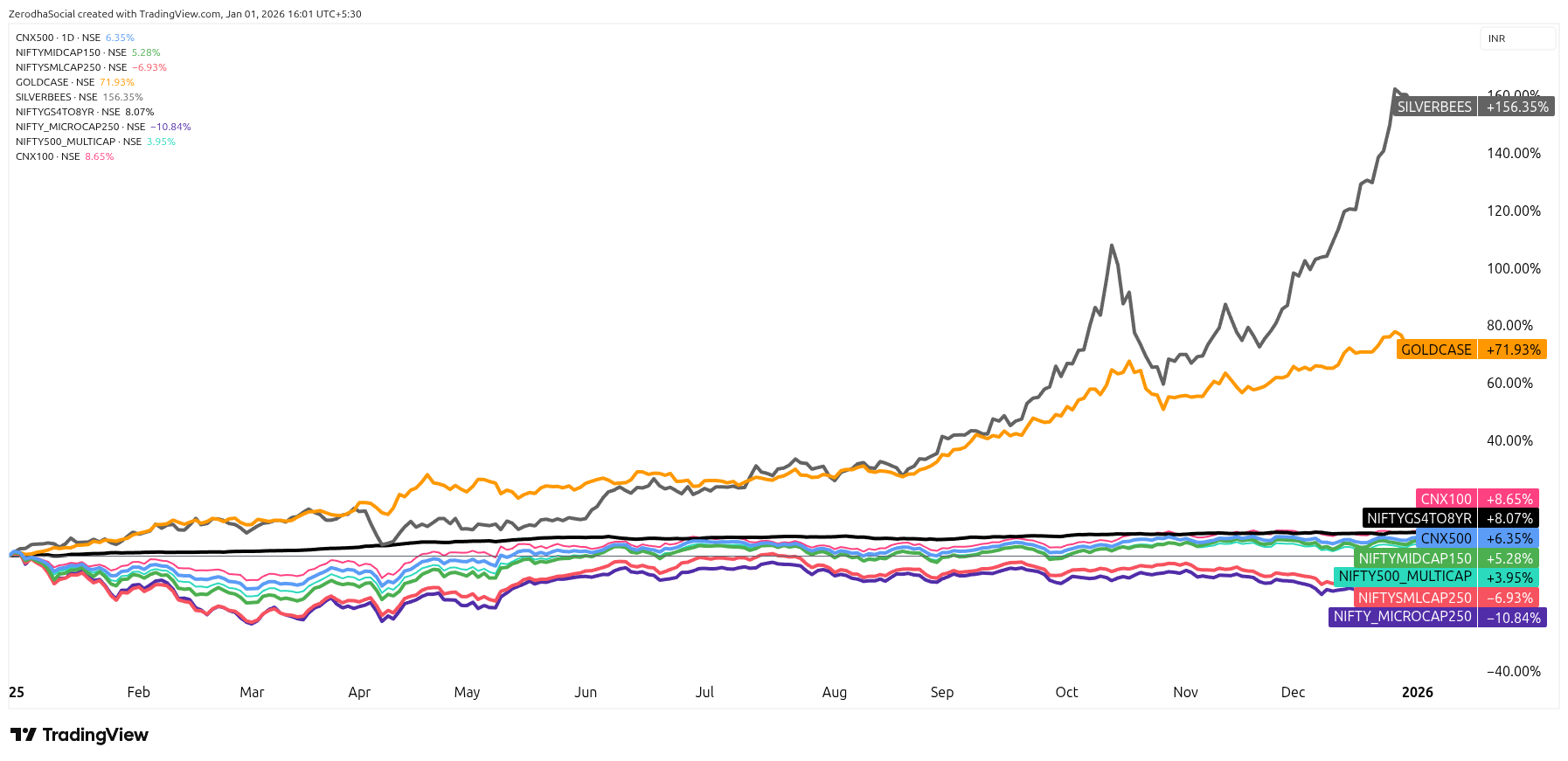

Nifty 500 returned ~6.3% this year. Government bonds? 8%.

There was this feeling among investors that 12-20% a year in equities is a god-given right, a fundamental right enshrined in the constitution. Turns out it’s not. It turns out that the stock market has the arrogance and audacity to underperform a fixed deposit.

Disgusting!

The Nifty multicap index which is a reasonable proxy for retail investors, was up just 3%. The Midcap 150 index was up 4%, the Smallcap 250 index was down 7.7%, and the Nifty Microcap index was down 12%. Considering the vertical rally in small and microcaps over the last 4-5 years, a lot of money flooded in. Turns out trees don’t grow to the sky. Turns out, in some spectacularly mind-bendingly world-endingly shocking news, stocks go down. How dare they?!

Meanwhile, commodities shined. Gold was up about 71%, and silver was up a mind-bending 156%. One of those once-in-a-lifetime rallies.

The big takeaway: what you expect and what happens are often opposites. Heading into 2025, many expected equities to do spectacularly well. The opposite happened.

2. Patience pays (even when trees stop growing)

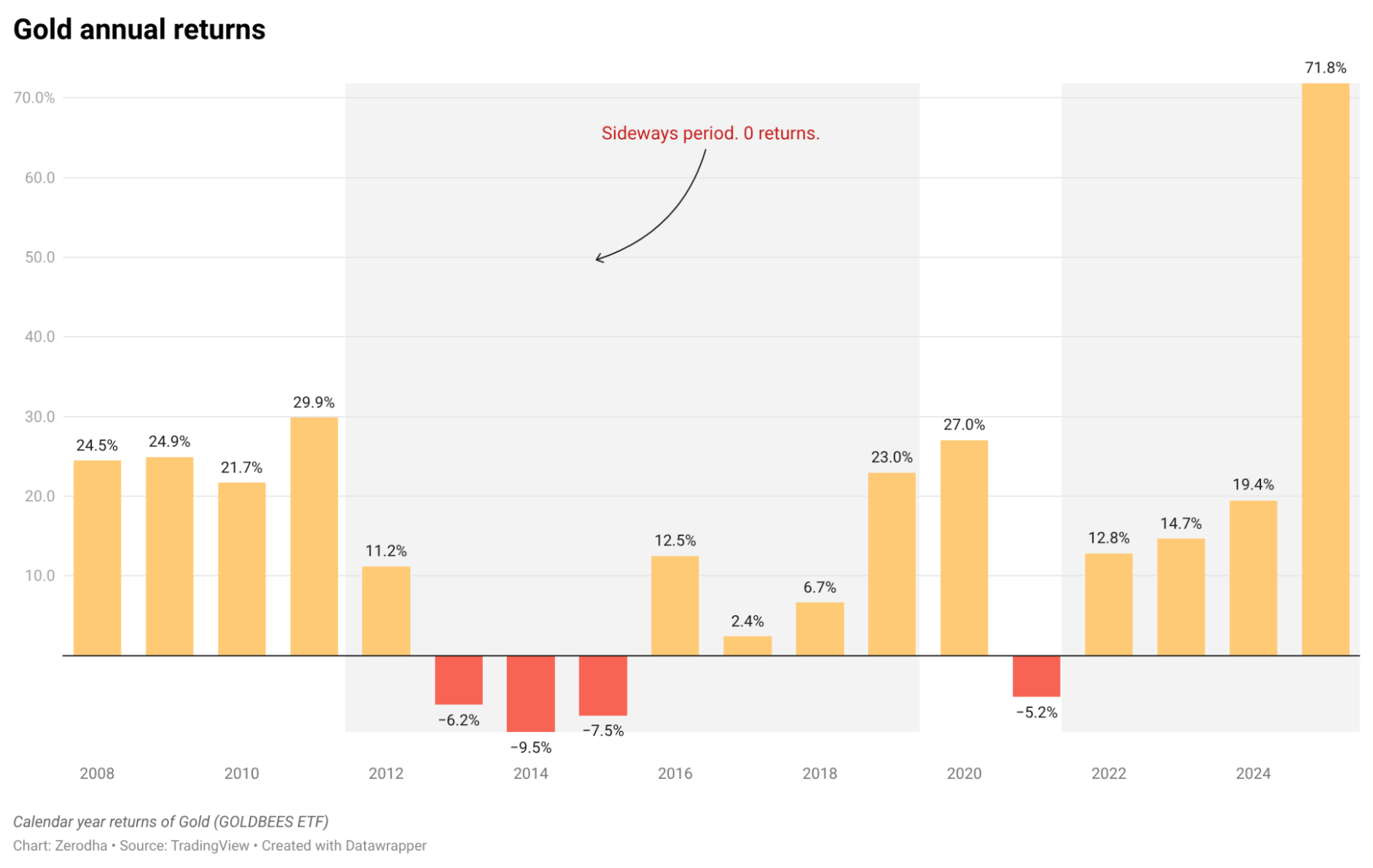

This extends the previous point, but gold illustrates it best. From 2012 to 2019, gold went nowhere. Stuck in a narrow range. Zero returns for close to a decade.

But since 2020, gold’s been on a spectacular rally, generating double-digit returns every year except for 2021, and since 2022, returns have gotten larger. But to realize these returns, you had to endure 8 years of nothing.

No asset class or strategy delivers positive returns every year. The only exception is Jim Simons’ Medallion Fund, but we mere mortals don’t have access to that. For normal people, expecting things to go up every year leads to heartbreak. Gold giving no returns for seven to eight years proves asset classes can go nowhere for long periods.

There is a patience premium for everything. I’m borrowing this term from Kathryn Kaminsky. She put it beautifully: there’s a premium to be harvested in asset classes going through drawdowns. If you stick to them like grim death—as Cliff Asness says—you can harvest that patience premium because most weak hands give up. They can’t resist the pain of underperformance. But if you stick around, the probabilities of doing well are much higher.

“I think the patience premium is really about the fact that many of these strategies tend to recover after drawdowns. There’s value in sticking with them over time, rather than looking at the bottom of the performance list and saying, ‘Well, that doesn’t work anymore.’ You recognize that these strategies are cyclical and are likely to come back given enough time.”

— Kathryn Kaminski

“The real magic skill is that despite some fairly horrific and none-too-short relative and absolute return periods, Buffett stuck with his style, and his risk level, like grim death. There’s no sign he ever backed off through multiple down years and drawdowns, including a horrific experience during the tech bubble when he underperformed by 76%.”

— Cliff Asness

3. The narrative apocalypse that wasn’t

2025 was weird. Indian and US markets diverged. Indian markets were in a bear market since roughly September 2024. But US markets started positive and stayed that way through Jan and Feb, while Indian markets kept falling until Feb.

Then came Trump’s Liberation Day on April 2. He announced sweeping tariffs on practically the entire world. Markets had a meltdown. The S&P 500 plunged 5% on April 3—the worst day since COVID. The next day? Down another 6%. By the end of April, the S&P had fallen 19%. Global markets lost trillions in value.

Suddenly, the narrative apocalypse began. Not just recession fears—full apocalypse mode:

The end of the global liberal order

- De-dollarization as the dollar collapsed (it did fall 11% in the first half—biggest decline since 1973)

- Tit-for-tat trade wars spiraling into global economic chaos

- Trump destroying the US economy

- “If the US sneezes, the rest of the world catches a cold.”

The doom was everywhere. Twitter was awash in macro porn. Podcasts debated whether this was 2008 or 1929. China and the US were trading tariffs that reached 145% and 125%, respectively. If you looked at sentiment in April, you’d have thought markets would be lucky to only fall 30% by year-end.

Then Trump paused the tariffs, markets rallied, and the Nifty 50, S&P 500, and Nasdaq hit all-time highs again.

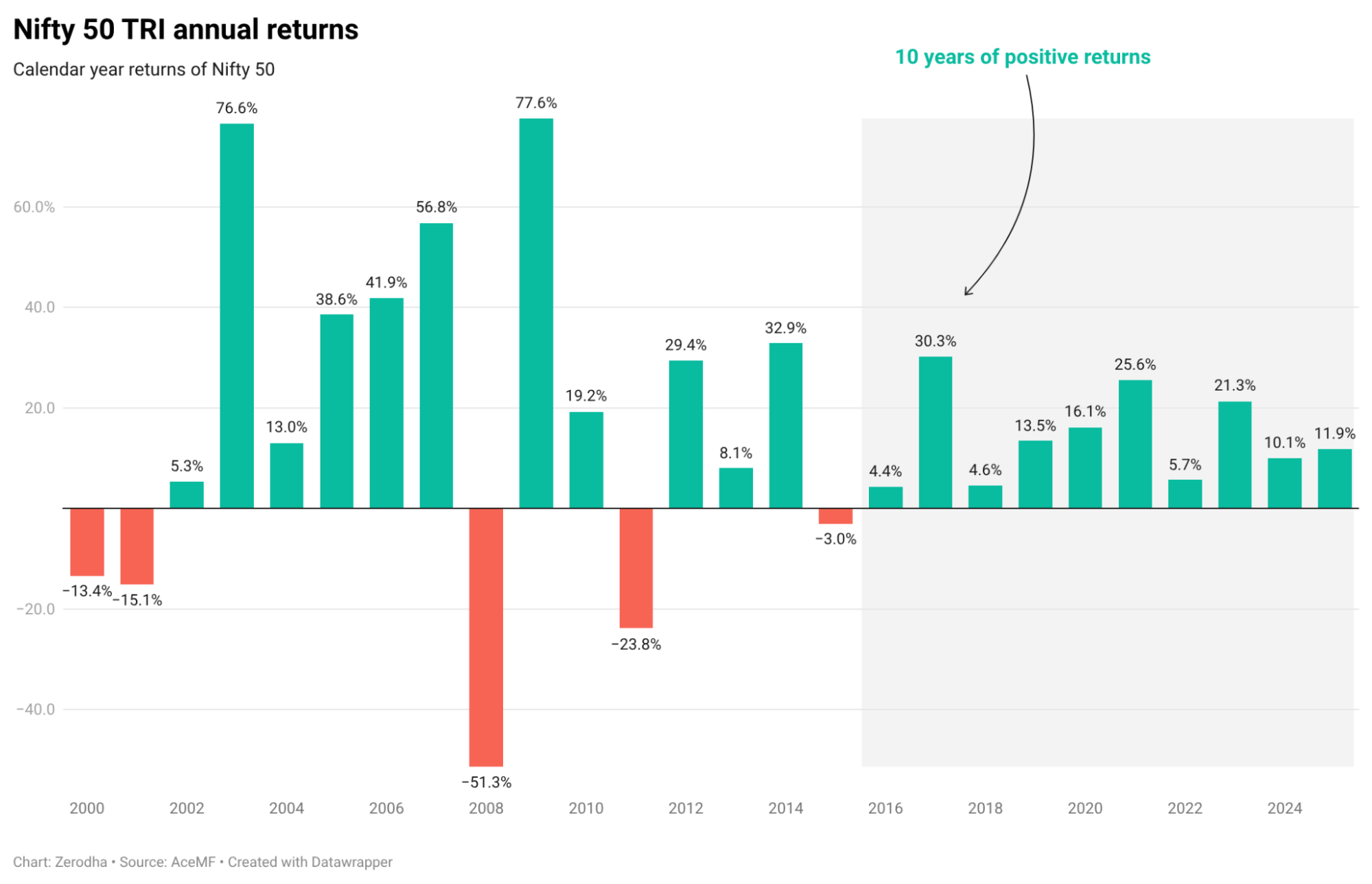

In fact, Nifty 50 has delivered 10 straight years of positive returns despite all the mayhem.

But 2025’s panic wasn’t just about tariffs. It was layered on top of bigger structural fears that have been building for years: US sovereign debt spiraling, conflicts in the Middle East and Ukraine, the India-Pakistan flare-up, the Taiwan question, US isolationism, the end of the “rules-based liberal order,” and the dawn of a multipolar era.

And that’s just geopolitics. Zoom out further, and you have the mega-trends that will reshape everything: aging demographics, climate change requiring trillions in green transition spending, AI potentially automating entire industries, and structurally higher inflation from defense spending and deglobalization.

These aren’t wrong. The world is changing. We’re probably at the brink of a very weird phase. Tech companies are throwing around trillion-dollar AI capex numbers like pocket change, racing to build a digital god in a box. Crypto morphed from a libertarian project into digital gold, then into the Trump trade—now it’s stablecoins and tokenization being pitched by the same people who mocked it five years ago. Climate change is real. AI is probably the greatest technological shift of our lifetimes. The sheer variance in possible futures—from complete devastation of knowledge work to total automation—is mind-boggling.

Here’s the trap: investors see these trends and think they can pick the winners. They study macro and imagine becoming the next George Soros or Ray Dalio, timing the market and generating alpha from these big structural shifts.

This is stupid.

Cullen Roche, CIO of Discipline Funds, put it perfectly:

“So much of this is about behavior. A lot of people study macro and think they’re going to beat the market and generate tons of alpha. Whereas I take it from the opposite view—macro is really about understanding the world for what it is so that as we navigate it and encounter the behavioral difficulties that are inevitable, we behave better because we feel more comfortable understanding these big-picture things that are incredibly confusing. It’s not about taking advantage of these things in an alpha-generating way. It’s about understanding the world so that we don’t behave badly.”

That’s it. Macro helps you not panic. It doesn’t help you make money.

The question isn’t “Are these trends real?” They are. The question is, “Can I pick which stocks, sectors, or markets will win from these trends?” You can’t. Very few people can

This reminds me of a Shakespeare quote I saw on Twitter:

“Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player, That struts and frets his hour upon the stage, And then is heard no more. It is a tale Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, Signifying nothing.”

Replace “life” with “macro narratives,” and the quote holds true.

The macro doom guys always say buy gold. They’ve been spectacularly right these last five years. To their credit, they nailed that call. But they’ve been horrendously wrong on everything else—namely the end of the world as we know it, much to their disappointment.

All they want is for the world to end one time so they can be right. Sadly, the world is not cooperating.

4. Boring worked. Again.

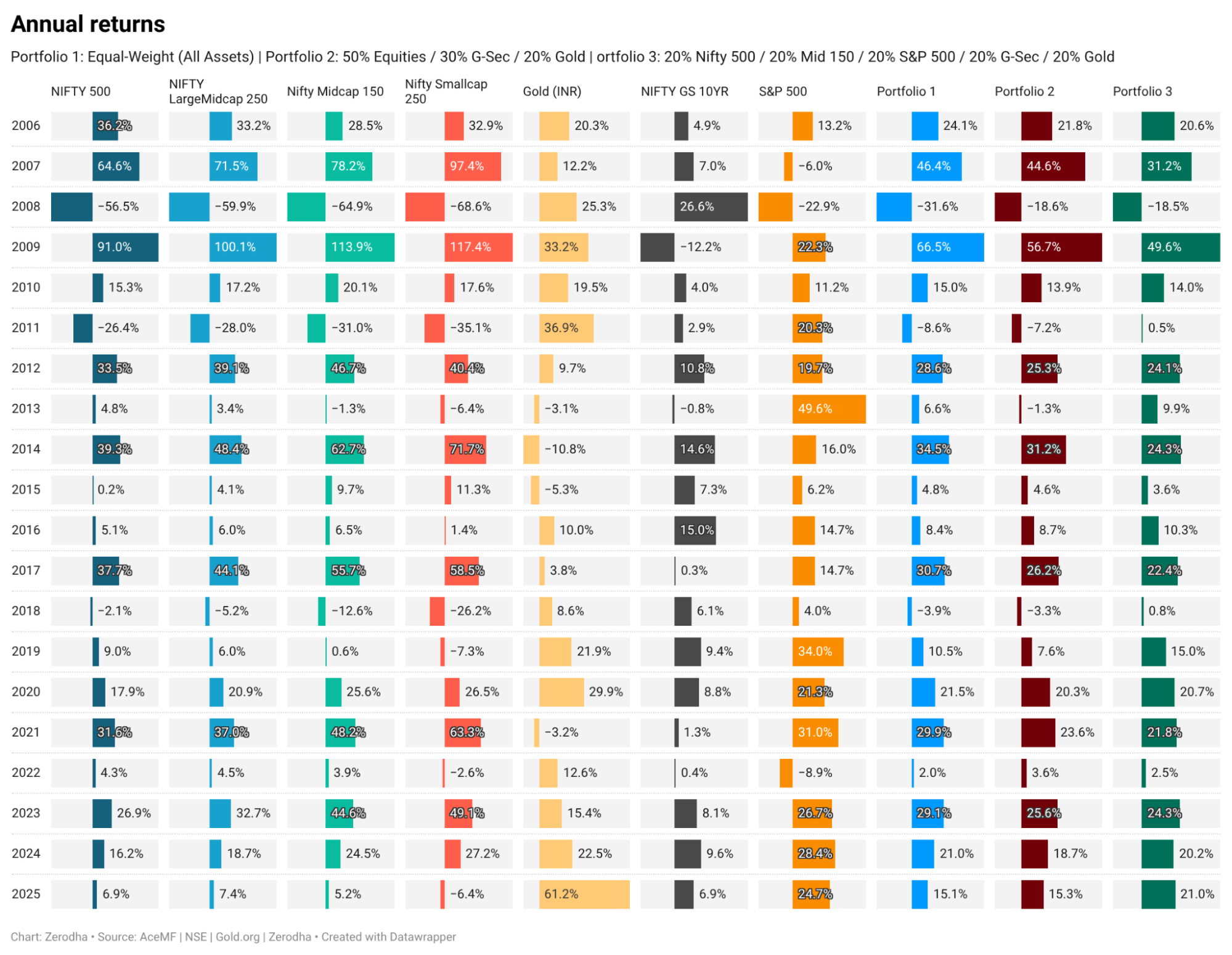

Every year I have this section, and the idea is simple: a well-diversified portfolio spread across different asset classes and rebalanced diligently has a higher probability of outperforming everything else. That held true in 2025.

Despite all the macro doom, boring multi-asset portfolios performed really well.

What does that tell you? One of the easiest ways to lose money is to go by the noise. As Mahatma Gandhi once famously said, “You live by the noise, you die by the noise.” Of course, he didn’t say that, but it’s true.

When it comes to investing, your ability to stand still when the entire world is going mad is the real superpower. I get it’s a cliché. I don’t mean buy and hold forever and never do anything. But activity in your portfolio and results are inversely proportional. The more you tinker, the more decisions you make, and the more trades you make, the higher the odds of generating poor returns—or worse, losing money.

I’ve been working at Zerodha for a decade. The stupidest way I keep seeing people lose money is by making investment decisions based on binary macro headlines:

- GDP bad? Sell stock.

- Inflation bad? Sell stock.

- Donald Trump farts? Sell stock.

- Kim Jong-un rattles his saber? Sell stock.

- Famous hedge fund manager reveals he’s wearing pink underwear? Sell stock.

This is the dumbest way to invest.

5. Know your market history

Given the sheer macro noise pollution this year, one thing got reinforced: the importance of knowing market history.

There’s often a misguided assumption that history helps people make money. That might be true. I often think about what historian Margaret MacMillan said in a lecture: History doesn’t give us answers, nor does it tell us what’s going to happen, nor does it offer a blueprint for the future. But it enables us to ask better questions.

“History can be helpful because it allows us to formulate better questions. It won’t necessarily give us clear answers or tell us exactly what to do. But if we don’t ask good questions, we have no hope of finding good answers. What history can do is help us think through scenarios—if we do a certain thing, what is likely to happen?”

— Margaret MacMillan

William Bernstein wrote about this beautifully. Knowing a bit of market history tells you you’ve seen this movie before. You get a sense of how things might play out. It shrinks the scope of possible futures and helps you sense the pattern. It helps you figure out a range of options based on the prevailing vicissitudes of the crowd.

“I’m old enough to remember what things looked like—not just in 2000, but also in 1974, in 1979, and in 1982, when BusinessWeek famously wrote about the ‘death of equities.’ There weren’t many people back then bragging about being 100% in stocks. The trouble with bubbles is that they can run for a very long time. I think the phrase that captures this best is “I can tell you what will happen—I just can’t tell you when.”

— William Bernstein

History didn’t predict the April 9 tariff pause. But knowing market history gave you the pattern: policy-driven sell-offs recover faster than fundamental crises. Trade wars, tariff threats, political chaos—markets have survived all of it. The better question wasn’t “Will markets crash?” It was “Is this a temporary policy shock or a permanent structural break?” If you knew your history, you would have recognized the playbook and wouldn’t have panic-sold into a 19% drawdown that recovered in two months.

6. If you can’t pick stocks, shut up

A few months ago, there was bitching and moaning about active mutual fund managers investing in “overpriced” IPO stocks. This debate always makes me laugh. Think about the absurdity.

Most people invest in active mutual funds because they can’t pick stocks. Put another way, they’re incompetent—if they picked stocks themselves, they’d lose money. That’s the entire logic of giving money to an active fund manager: because the manager is better at the task than the individual retail investor. The active fund manager is the superior creature. The average individual investor is the inferior creature. Those are the facts.

When you give money to someone who’s smarter than you and knows how to manage it, you should let them do their job. That’s the whole point of picking an active fund.

You can’t suddenly go from being incompetent to being an expert on valuing private companies just because the active fund manager picks an IPO stock. This is what happened recently with the retail investors crying, “Oh, the active fund manager is investing in overpriced stocks.”

Remember, the same retail investors had absolutely no skill picking stocks. Now, suddenly, they’re an expert on valuing IPO companies. I’ve come up with a short rule: If you can pick stocks, pick stocks. If you can’t pick stocks, give money to an active fund manager and shut the %*#@ up.

7. The IPO delusion

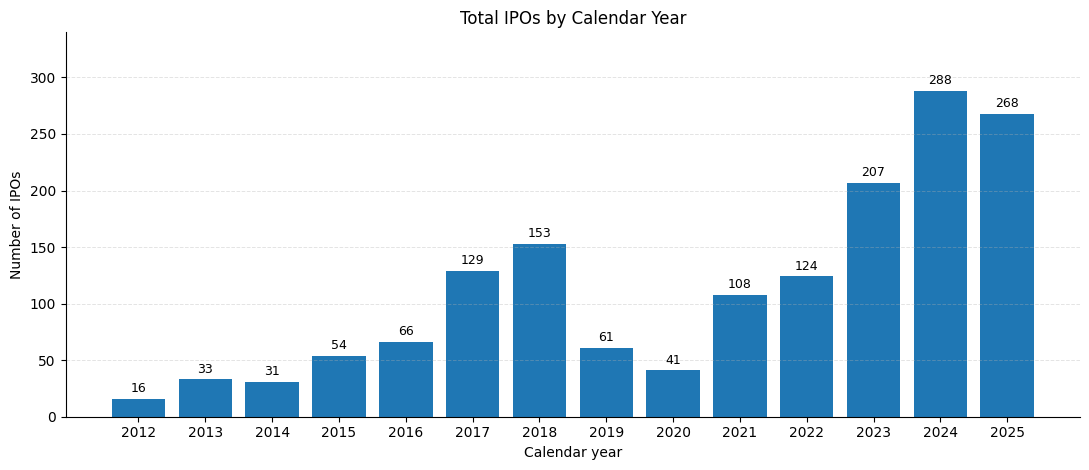

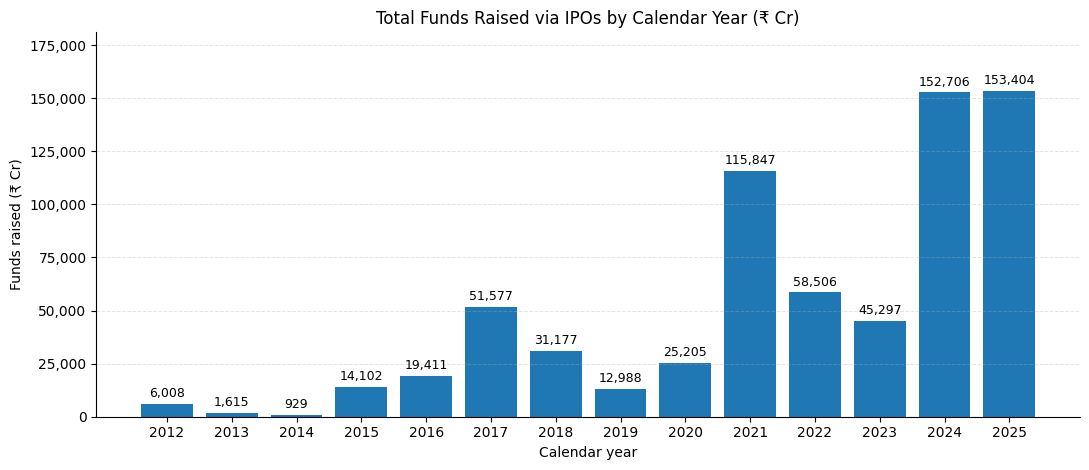

2025 was a banner year for IPOs. Companies raised ₹1.53 lakh crores—nearly identical to 2024’s ₹1.52 lakh crore. Two consecutive years of heavy issuance. The IPO machine was running full tilt.

Retail investors love IPOs. There’s this widespread delusion that you can get rich betting on IPOs. Apply for every IPO, get that listing gain, rinse and repeat. Easy money, right?

Wrong.

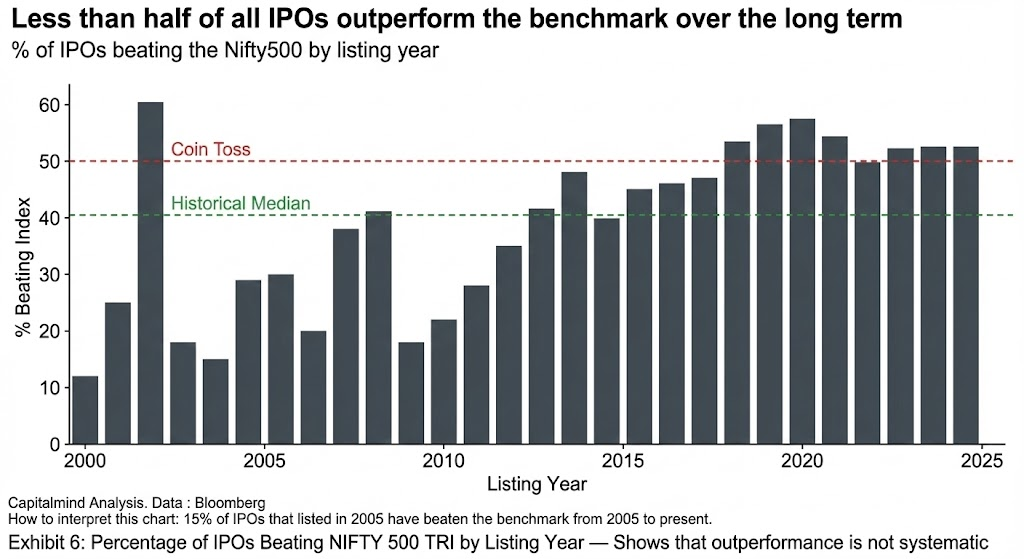

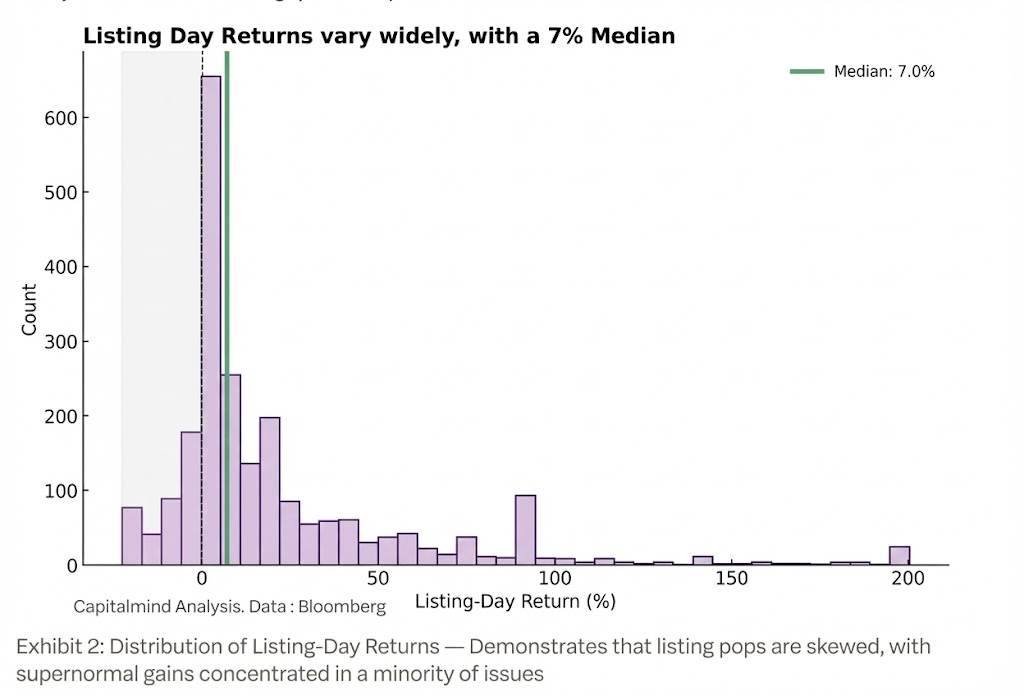

The folks at Capitalmind ran the numbers, and they’re brutal. Only 40% of IPOs beat the Nifty 500 index long-term. That’s right—less than half. You’d have better odds flipping a coin.

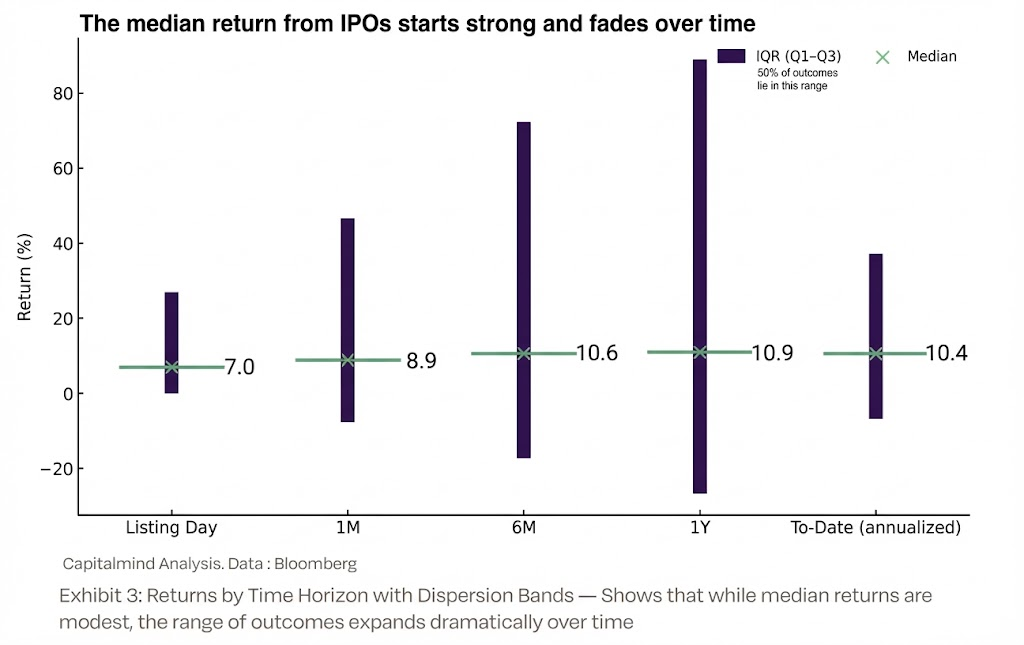

But wait, what about those juicy listing gains everyone brags about? The median listing gain is 7%. Seven percent. That’s it. And here’s the kicker: those gains evaporate faster than your New Year’s resolutions. A few months later, most IPO stocks are trading below their listing price.

The data gets worse. When IPO issuance is heavy—like in 2024 and 2025—future returns tend to be poor. It’s a supply-demand thing. When companies are rushing to raise money, they’re timing the market. They know valuations are elevated. They’re not idiots. They’re selling at the top.

And large IPOs? They’re the worst. Smaller IPOs (under ₹200 crore) tend to outperform larger ones. The big, hyped IPOs tend to do poorly

The lesson: IPO investing for retail investors is mostly pointless. You’re not getting special access. You’re not getting a sweetheart deal. You’re getting what’s left after institutional investors cherry-picked what they wanted.

8. Stock picking is harder than you think

Picture this: You discover the stock market. Read the news for eight minutes. Suddenly you come across “technical analysis” and “fundamental analysis.” You decide fundamental analysis is easier than being a grown man drawing random lines on a chart.

You discover companies file annual reports. You go to Tijori Finance. In 77 seconds, you skim the financials. Sales up, margins up, profits up. Stock is good. Repeat for 15 stocks.

Now you’re now a smart, informed investor.

Then you check your WhatsApp groups. All your stocks are already being discussed by retired uncles, aunties, and that one random person nobody knows. Your ego hits lifetime highs. You voice-type your “thesis,” dump it into ChatGPT, and ask it to confirm your bias. ChatGPT, being the willing sycophant it is, agrees enthusiastically.

Six months later, twelve of your stocks made money. You crack open a beer to celebrate. Then you check the Nifty 500: up 22%. Your portfolio: up 16%.

What the hell just happened?

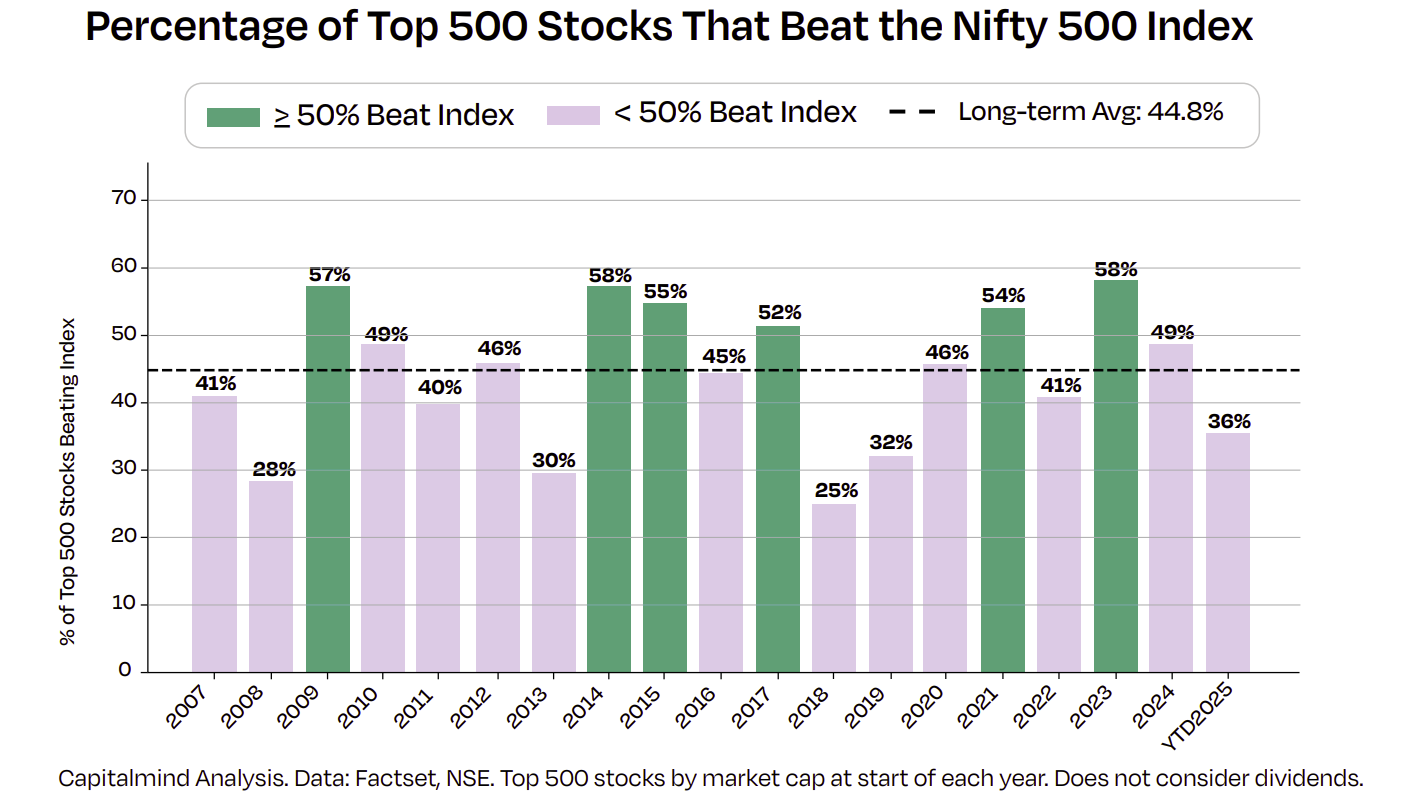

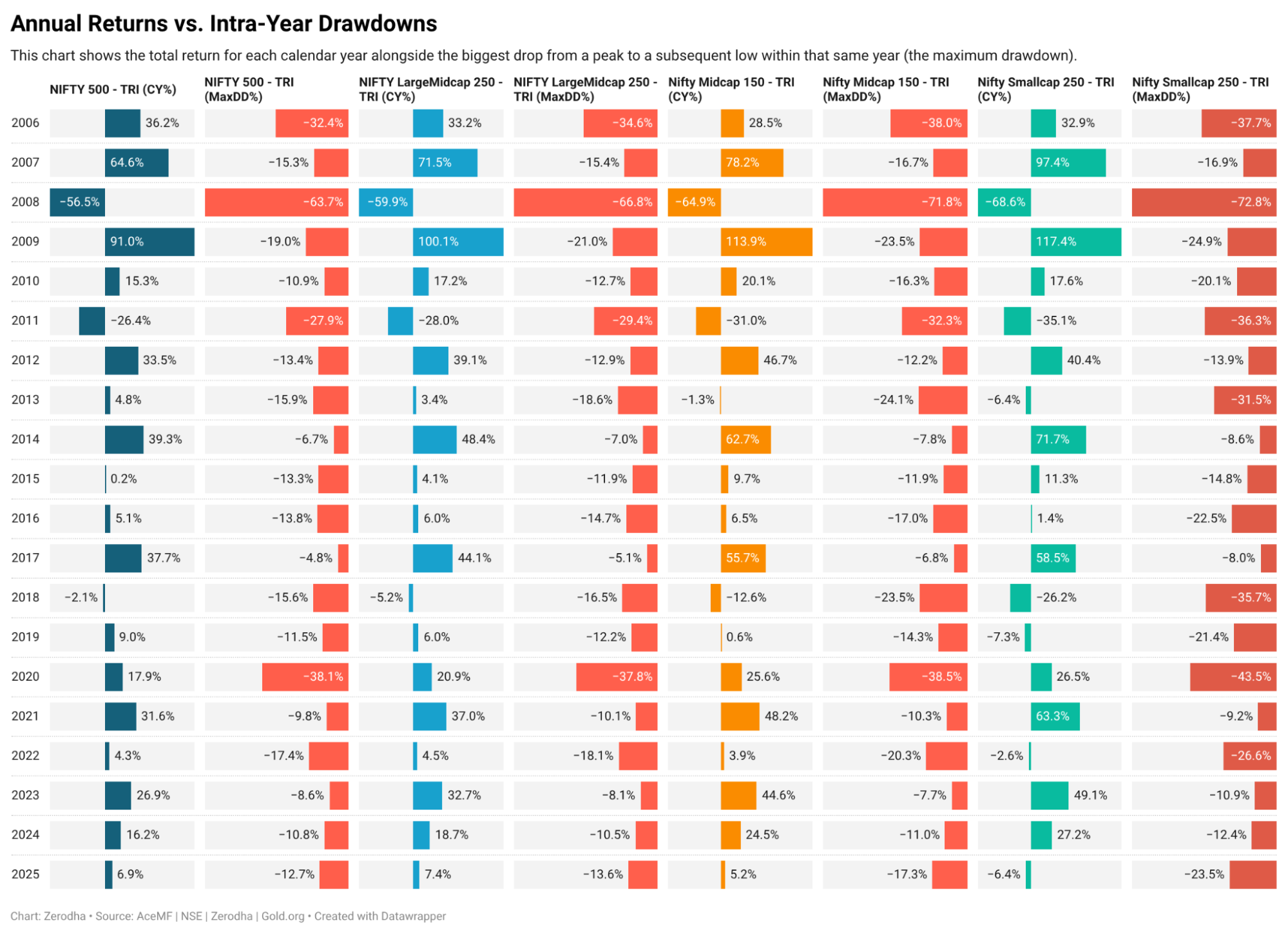

In a typical year, only 45% of stocks beat the index, according to this analysis by Capitalmind. Fewer than half the stocks in the index beat the index itself. Some years are worse: 2008 saw 28%, and 2018 saw 25%. From 2016 to 2020, beat rates were stuck at 25-36% for four straight years. Even in “good” years, only three out of 18 years saw more than 55% of stocks beat.

The problem is that the index isn’t the typical stock—it’s a cap-weighted outcome where a handful of stocks drag the whole number up. The median stock almost always trails the index. To beat it, you need to land in the top 40-45% of all stocks. Every year. Consistently.

Good luck with that.

“But I’m a long-term investor!”

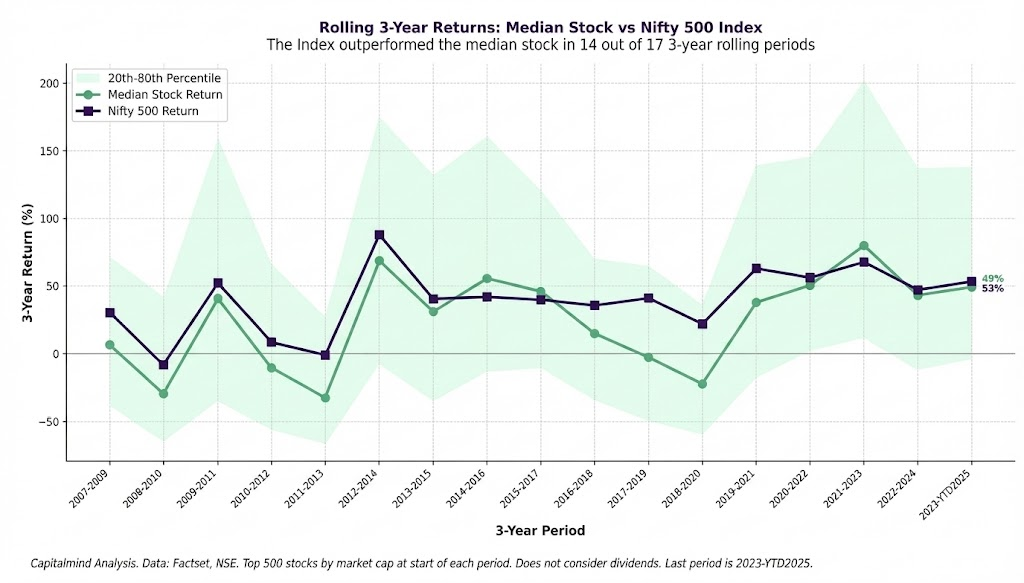

Adorable. Over rolling 3-year periods, only 42% beat the index. This is worse than the annual figure. Underperformance compounds. You’re not catching up. You’re falling further behind while congratulating yourself on being patient.

Here’s the absurdity: the top 10 stocks over 3 years returned a 508% premium over the index. Top 20? 392%. Top 50? 260%. These stocks went to another dimension. Returns are concentrated in a tiny cluster of outliers you can’t identify in advance.

The top 10 performers of 2019-2021 weren’t the top 10 of 2016-2018. Winners keep rotating, and they don’t persist. Only 47% of winners continue winning in the next period. Then just 22% in the period after that.

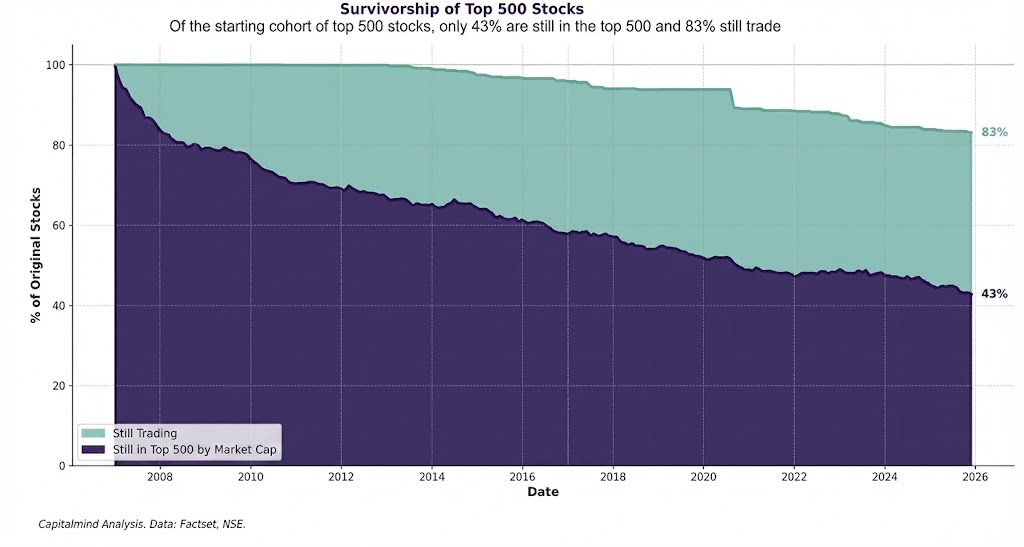

Meanwhile, the index self-heals like Wolverine. Of the 500 stocks in the top 500 in 2007, 43% are still there, 40% became irrelevant, and 17% are dead. The index ejects failures and promotes winners automatically. You have to decide when to sell. The index does it without emotion or Twitter confirmation bias.

The chart shows this attrition in real time. By 2012, only 70% of the original cohort remained in the top 500. By 2018, barely half. Today, 43%. The decline is relentless and one-directional. The index isn’t passive. It’s a systematic strategy with simple rules: add stocks that grow large enough, remove stocks that shrink. Weight by market cap, which means let winners run. This looks like doing nothing, but you can almost call it a momentum strategy with automatic rebalancing. When you pick stocks, you’re not just competing against 500 companies. You’re competing against a portfolio that quietly ejects its failures & promotes its successes. An active investor has to decide when to sell; the index does it automatically, without emotion. — Capitalmind

This isn’t a retail problem. SPIVA data shows most professional fund managers—people with Bloomberg terminals, research teams, and six-figure salaries—underperform their benchmarks. If the pros struggle, what chance do you have?

Assuming stock picking is easy means you’re either unfamiliar with the evidence or smoking something. Roughly 55% of stocks lose to the index annually. Over three years, 58% lose. The investors who beat the index long-term respected the difficulty from the start.

9. Markets go sideways for decades

The one thing I’ve been crying about for 4-5 years: making money in the stock market isn’t as easy as it was post-COVID. In the last five years, markets went up in a straight line, and everybody ended up looking like geniuses.

Among investors, there’s this sense that making money in markets is easy. But this sense betrays not only stupidity but also historical ignorance. The problem with Indian markets is that we have limited historical data. Clean data only goes back to 1980 with the Sensex. But if you look at markets like the US, with 150-200 years of clean data, you’ll notice there have been long periods of zero to negative returns.

History may not repeat, but it rhymes. There is no ironclad rule that markets always generate positive returns year on year.

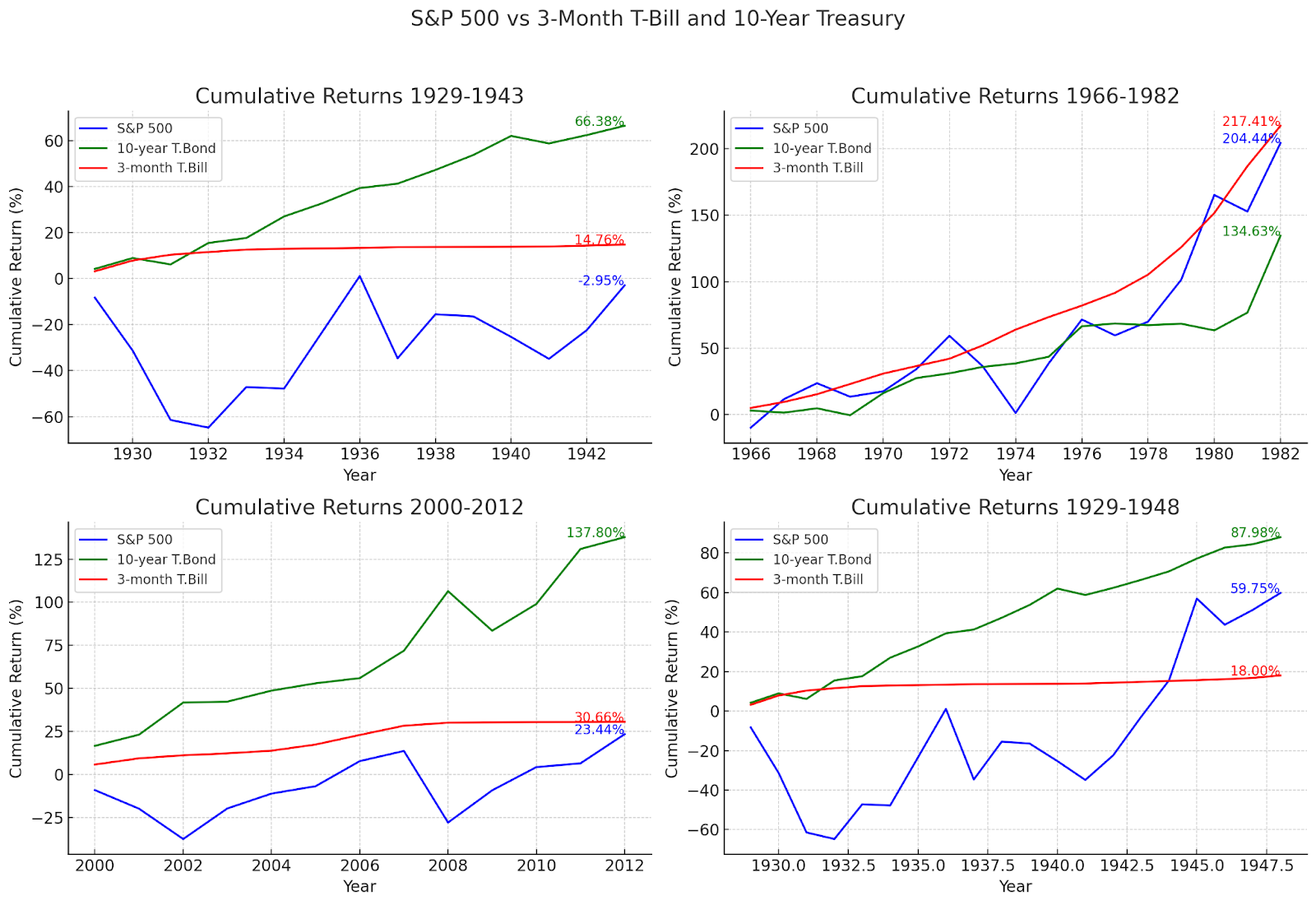

Just to give you some sense of how bad things can be:

- 1929 to 1943: S&P 500 underperformed 3-month T-bills for 15 years

- 1966 to 1982: S&P 500 underperformed 3-month T-bills again for 17 years

- 2000 to 2012: S&P 500 underperformed both 3-month T-bills and 10-year Treasury bonds

- US small-cap stocks: Underperformed large-cap stocks by 2.8% per year since 1926

- Gold, 2011 to 2019: 7-8 years of 0% returns

We’re talking periods of almost a decade to two decades. That’s how bad it can get.

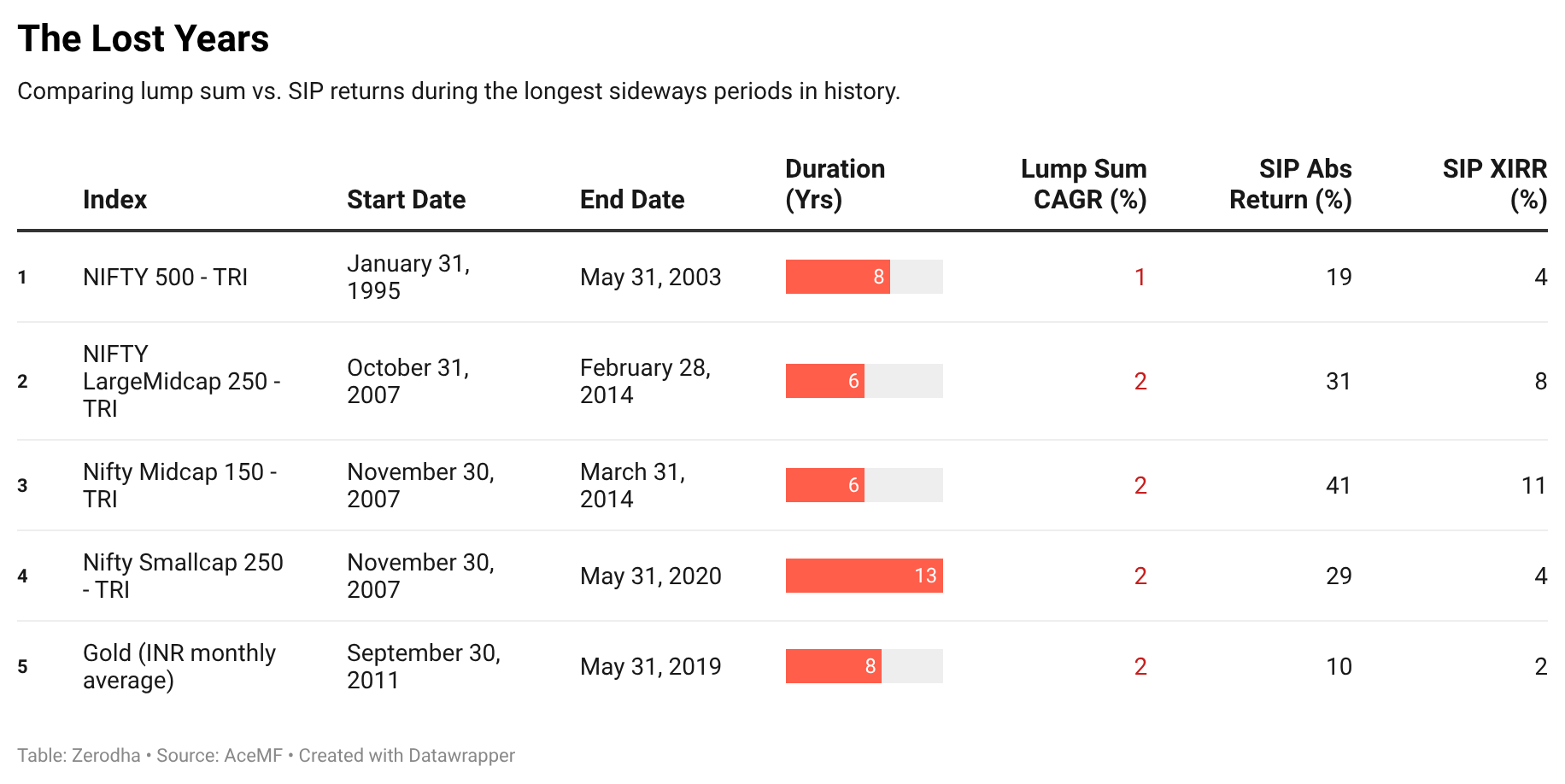

Even with limited data in India, we’ve had rough periods:

- Nifty 500, 1995 to 2003: 0% returns for 8 years (yes, this IS total returns data, including dividends)

- Large mid-index, 2007 to 2014: 6 years sideways; SIP was better at 8%, but debt funds would have been 6-7%

- Nifty Midcap 150, 2007 to 2014: 0 returns for 6-8 years

- Nifty Small Cap Index, 2007 to 2020: 0% returns for 13 years. How’s that for “small caps always generate higher returns”?

To be a good investor, internalize that really bad things can happen when you expect them least, and these bad periods can last longer than you realize.

The reason you earn a premium for investing in equities over fixed deposits and government bonds is you’re getting paid to deal with this uncertainty for prolonged periods. That’s the biggest reason for the equity risk premium. If you can’t handle the uncertainty and don’t want higher expected returns than debt and government bonds, you have no business in the stock market.

The last 5-6 years have been an aberration. Making money has been easy, but these periods don’t occur often. Don’t get used to it. The other thing most people don’t know is that even in good years, things get rough. A 10-15% fall is almost guaranteed even in good years. But when things get bad, they get really bad—see 2008 and 2020.

10. Valuations are high—timing is impossible

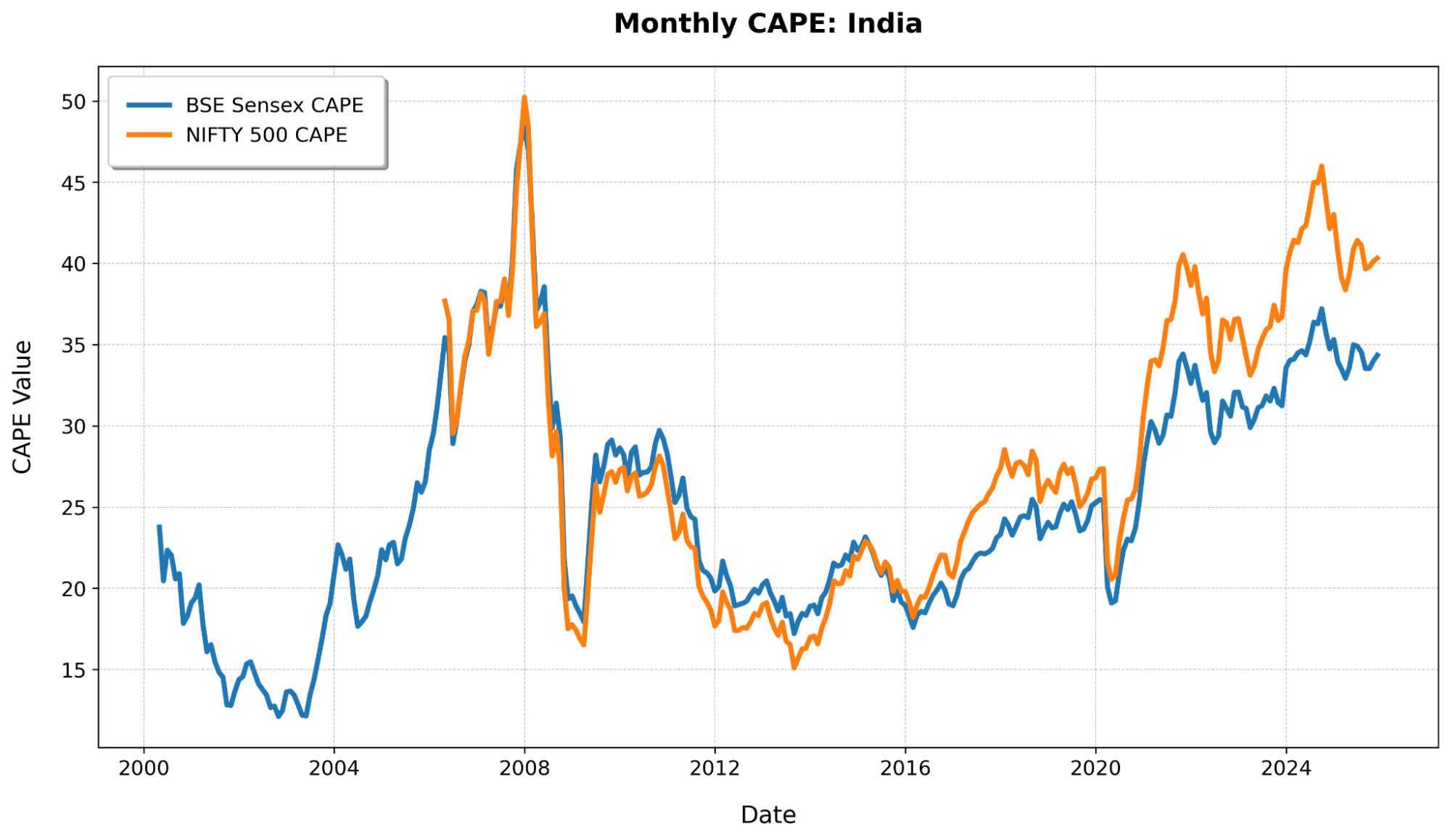

No yearly post is complete without looking at market valuations. For various reasons, I don’t prefer the P/E ratio of Nifty—there are issues with that data. But luckily, Professors Rajan Raju and Joshy Jacob of IIM maintain data calculating the cyclically adjusted price-to-equity ratio (CAPE) for Indian markets. It’s a popular measure created by Professors Robert Shiller and John Campbell.

The funny thing about valuations is just because they’re high doesn’t mean the market has to crash. The stock market can remain overvalued for longer periods, and it’s hard to appreciate all the structural reasons that elevate valuations.

My way of looking at valuations is dumb and mechanical. If your starting valuation is high, future expected returns tend to be low. If starting valuations are low, future expected returns tend to be high. There’s enough evidence this relationship holds more or less true, but over a very long period.

That doesn’t mean you can use valuations to time the markets. In fact, it’s the stupidest way to time markets. You’re better off looking at horoscopes, kundalis, or bird droppings—your hit rate will be much better.

As things stand today, we’re at historic highs in terms of the CAPE ratio for Indian markets. In fact, we’re at only the second-highest level since 2008. That means it’s a reasonable bet that future expected returns for Indian markets will be much lower than what you’ve seen in the last five years.

Remember, at the bottom of COVID, market valuations were abnormally low, and they more than made up for that with spectacular returns since.

So if you have this arrogant expectation that it’s your god-given right to get 15% in Indian equities no matter what, and this right has been enshrined in the Indian constitution, I hate to break it to you: you’ll probably underperform a government bond.

11. Things change—always

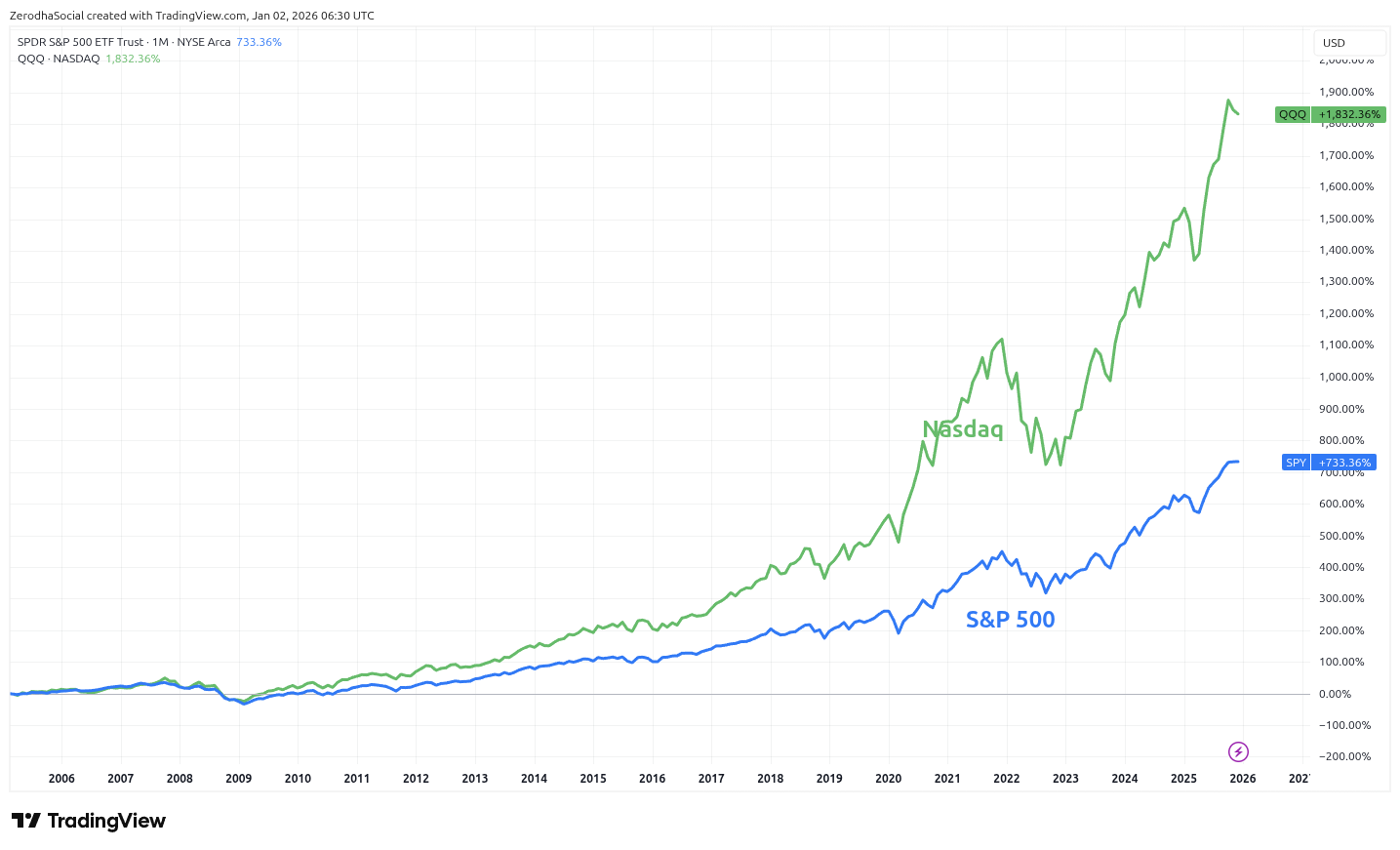

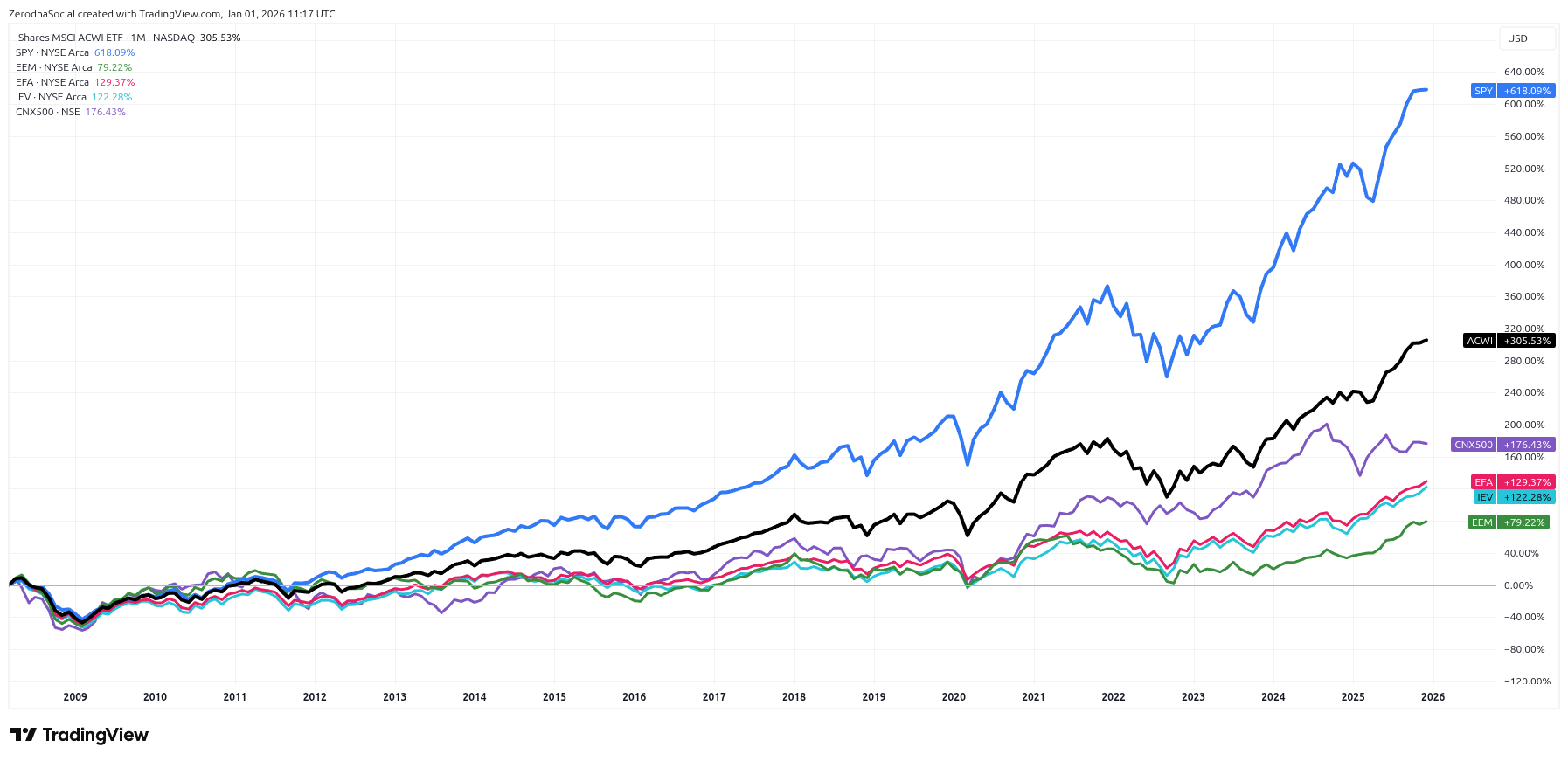

Since 2008 roughly, the only game in town across the world was US markets. The S&P 500 beat everything by a mile and more. Nothing came close. Even Indian markets, which did phenomenally well in the last five years, didn’t come close.

SPY – S&P 500 ETF | ACWI – MSCI All Country World Index ETF | EEM – iShares MSCI Emerging Markets ETF | IEV – iShares Europe ETF | EFA – iShares MSCI EAFE ETF |

But look at the one-year chart, and things suddenly flip. Due to various reasons—which probably nobody knows—the US market is now materially underperforming the rest of the world: emerging markets, Europe, and others. Whether this underperformance continues, we don’t know.

If you’d gone by the headline narratives that the US market is outperforming everything because of the MAG-7 stocks, you would have noticed that this year, the rest of the world has been beating the daylights out of the US markets.

And look at Indian markets in dollar terms—our returns are basically zero.

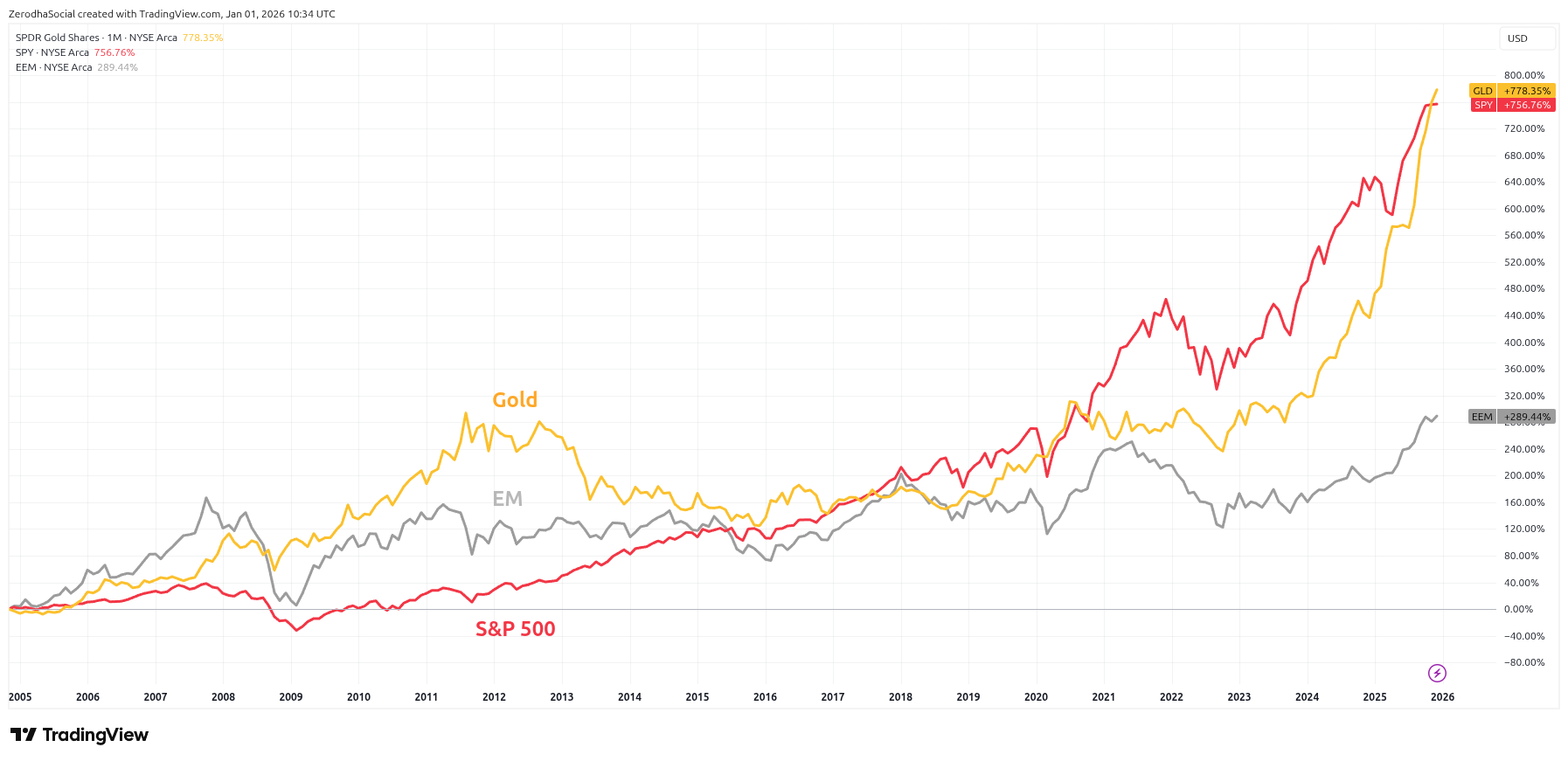

Here’s another interesting chart comparing GLD (a gold ETF in the US) with SPY (the S&P 500 ETF). You can call this cherry-picking, but I’ve taken this from the inception of the ETF in 2005. Gold, despite all the narratives that it’s useless, a shiny pet rock with no dividends and no returns, has managed to outperform the S&P 500.

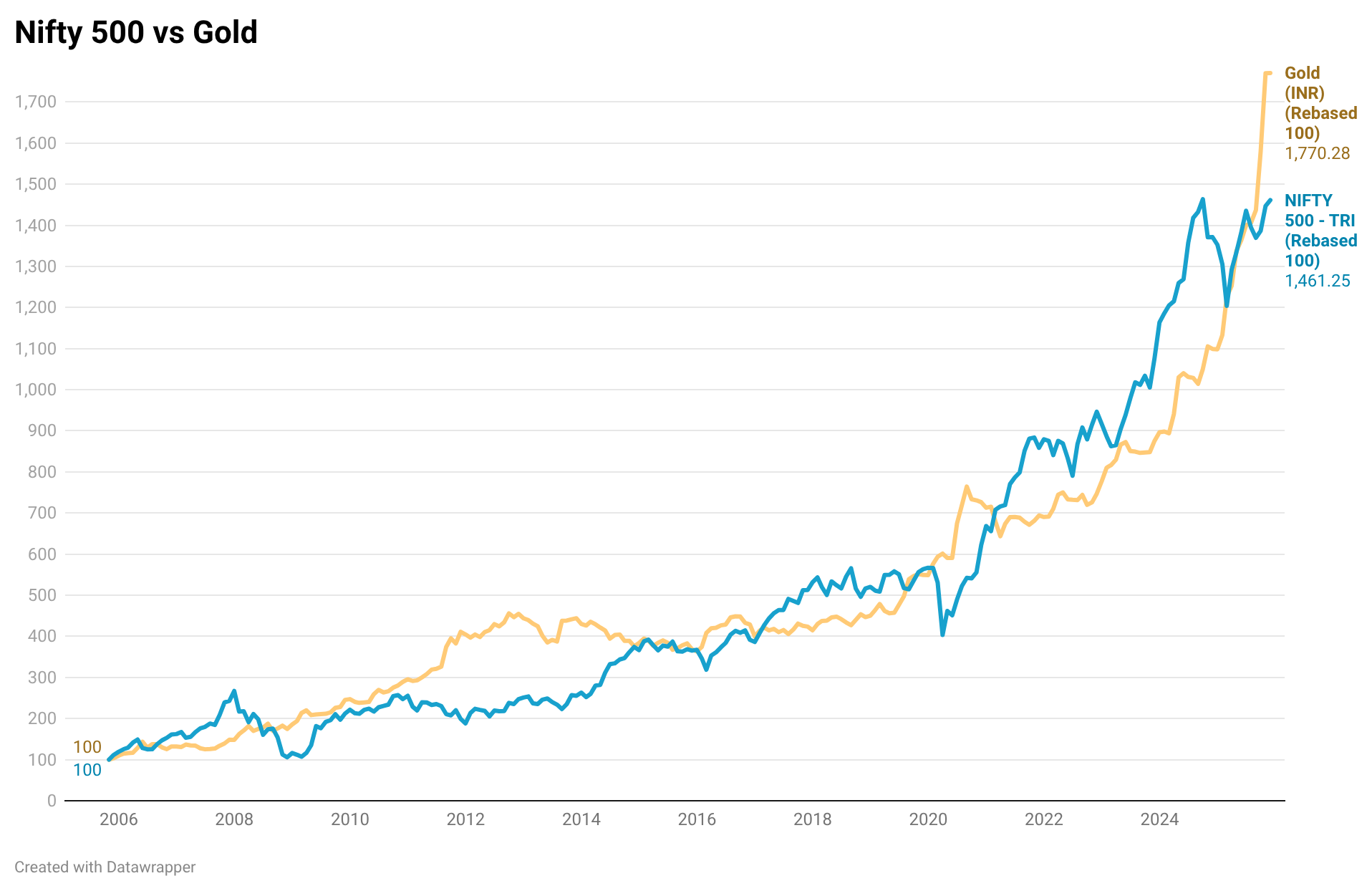

This is a funny chart for me because the dominant narratives about gold don’t square with reality. I looked at the same thing in Indian markets. Using clean gold data from 2005 from the World Gold Council, gold has outperformed Nifty 500 TRI by a fair amount, thanks to the recent rally.

Don’t go by headline narratives. If you look underneath, a lot of things seem weird and different.

12. On having a philosophy of money

I’ve been thinking increasingly about the idea of a philosophy of money for a long time, and I recently wrote a semi-structured post. My thesis is this: the biggest reason people have money-related disasters is they lack a philosophy of money. I know “philosophy” sounds douchey, but bear with me. I mean it in the colloquial sense—a framework, a set of guiding principles.

The paradox is that people develop complex philosophies for life, but when it comes to money, they have nothing. We spend more time choosing underwear than thinking about financial decisions. Then we gamble life savings based on WhatsApp tips or some loudmouth on YouTube. The same creature that went to the moon buys penny stocks based on random tweets.

Most people have a thin, unconscious philosophy borrowed from family and society—never questioned, never examined, but running the show anyway.

A philosophy is your operating system. It’s the foundational layer beneath all your thoughts and decisions. When you face a tricky moment, this is what you reach for. Your financial philosophy should be an extension of your life philosophy. If you’re deliberate about life, be deliberate about money. If ethics matter in life, they should matter in money decisions.

Having a philosophy of money is important because money is not just a piece of paper. It’s a container for all our emotions, hopes, fears, and desires. These emotional aspects don’t play well with logic and rationality. Realizing that is the first step. Having a philosophy shrinks the scope of money in your head. It reduces the mental space money occupies and leaves room for other things that matter.

What does this look like in practice?

My own philosophy is to seek resilience over return maximization. I come from a typical middle-class family, which means money was always a source of problems and deprivations. So for me, avoiding financial shocks carries more weight than generating “maximum returns.” Being financially bulletproof became core to my philosophy. My first priority is resilience rather than wealth, and that means being able to absorb whatever random, chaotic things life throws at you.

Your philosophy won’t look like mine. It shouldn’t. But having some coherent framework that extends from how you think about life to how you think about money is what separates deliberate financial decisions from spectacularly dumb ones.

13. The golden age of fraud

The legendary short-seller Jim Chanos once called this “a golden age of fraud.” He was talking about corporate accounting shenanigans, but the phrase applies to individual investing too.

Social media has made investing exponentially harder. Pre-internet, the contagion vector for stupidity was limited—your friends, neighbors, and maybe colleagues. Now you can import stupidity from anywhere in the world with zero barriers. Twitter, WhatsApp, YouTube—your entire feed is a looking glass into humanity’s worst financial instincts.

We’ve never had this many financial gurus. Anyone can be one. Bare minimum effort—now even less thanks to AI—and you can build a profitable business scamming people. Selling courses, pump-and-dump schemes, fake advisory, and phishing scams. The career opportunities for aspiring fraudsters have never been higher.

Take Avadhut Sathe. SEBI raided his Karjat Trading Academy in 2025 and found he’d collected ₹546 crore from 3.37 lakh investors selling “courses” that were actually illegal investment advisory. He paraded a homemaker claiming she made ₹1 crore trading options—she’d made ₹4.2 lakh. Meanwhile, Sathe himself had lost ₹6 crore in his own trades. But the courses kept selling. The grift worked beautifully until the regulator showed up.

The surface area for infection has never been wider. It’s never been easier to feel FOMO because someone’s flaunting P&L screenshots. It’s never been easier to get jealous of perceived riches or someone’s lifestyle. It’s never been easier to jump on a narrative because lines are going up and yours isn’t. It’s never been easier to believe the guru promising double the returns with half the risk—or better yet, double the returns with zero downside.

We’re saturated with information we can’t possibly process rationally. The internet has accelerated mob dynamics. Starting a pump-and-dump has never been simpler. We saw it with crypto and meme stocks in the US. We’re seeing it in Indian small and microcaps—pumps happening in real-time on Twitter, WhatsApp, and Telegram.

Doing the logical thing in this environment requires superhuman fortitude. The noise is everywhere. The gurus are infinite. The scams are sophisticated. And you’re just one tweet away from doing something spectacularly stupid.

The only defense: know what you don’t know, stick to boring fundamentals, and mute the noise.

So, what did you learn?

Thanks Bhuvan for such a comprehensive walk through.

The key take away for me is the old school advice of diversification as per risk appetite and following a philosophy without diverging to much due to noise of other market or societal events.

Wishing you the best and looking for more such.

Best,

Aviral Singh

Hello Bhuvan,

Thanks for insight and understanding. As a common salaried person without much knowledge on how to pick stocks. Can you guide me some steps to choose good stocks or mf or investment strategies?

Very nice article and lots of information! Good closing on 2025 !!

Regards,

Kavitha

Hi,

I always look forward to this. Keep up the good work.

Hi Bhuvan,

I enjoyed reading this article. I guess my favourite sections were Philosophy of Money and the part where you showed how 3 Portfolios have performed over the years.

Since I am still young and figuring out my own ”Philosophy of Money” and most importantly haven’t really seen a bad period in the market (I started investing since 2021) those two sections made me think a bit more harder about how I deal with money and investments

Thanks,

Buvan (Yes, we have the same name)