The AI-shaped hole in personal finance

Caveat: This is a speculative post on what the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) means for one’s personal finances. The post has more questions than answers, so much so that you might even think, “What the hell is this fellow saying?” This is deliberate.

Given the inherent uncertainty associated with AI, any opinion on it has to reflect the uncertainty. Opinions filled with certainty would not only be wrong but also intellectually dishonest. Also, if you came here expecting tips on what AI stocks or funds to buy, I’m sorry. I have a lot of flaws, but being an astrologer is not one of them.

The old frameworks are dead, the new ones are struggling to be born, now is the time for questions

Get a good education, find a stable job, work for 40-50 years, save part of your salary, buy a home, and retire comfortably at age 65—this is the personal finance playbook for most people. We were using the tools of personal finance to transform the certainty of the present to prepare for the uncertainty of the future.

Even though the future was uncertain, we knew the variables and the range of possibilities to plan for. We had to worry about our health, career volatility, life events, and market volatility. The assumption at the heart of financial planning was that the future would look like a fuzzy version of the past—not the same but similar.

This assumption more or less held true for most of modern economic history.

What if it no longer holds true?

When you’re uncertain about both the present and the future, how do you think about money?

This is what artificial intelligence (AI) threatens to do today. Threatens being the operative word.

Suddenly, it looks like there’s about to be an AI-shaped hole in all our personal finances. We are possibly on the precipice of a technological shift that threatens to change, if not completely rewrite the predictable economic rules that underpinned modernity. We may be entering a time where we are forced to re-evaluate all our assumptions about money.

The ‘God-shaped hole’ is a modern interpretation of an idea most commonly attributed to the 17th-century French mathematician, physicist, and philosopher Blaise Pascal. The phrase describes the inner void we try to fill with status, material possessions, and distractions—a void that can only be filled by something transcendent.

“What else does this craving, and this helplessness, proclaim but that there was once in man a true happiness, of which all that now remains is the empty print and trace? This he tries in vain to fill with everything around him, seeking in things that are not there the help he cannot find in those that are, though none can help, since this infinite abyss can be filled only with an infinite and immutable object; in other words, by God himself.” — Blaise Pascal, Pensées

By “AI-shaped hole,” I am talking about a similar void that may be forming in personal finance due to the rise of AI. We’ve always relied on a simple equation: earn, save, and spend later, but now AI is threatening to upend this equation. Where there was certainty in how we thought about money, there’s about to be an “AI-shaped hole.” What or how we will fill that void is unclear.

Here’s how the economist Tyler Cowen described the rise of artificial intelligence in a recent post:

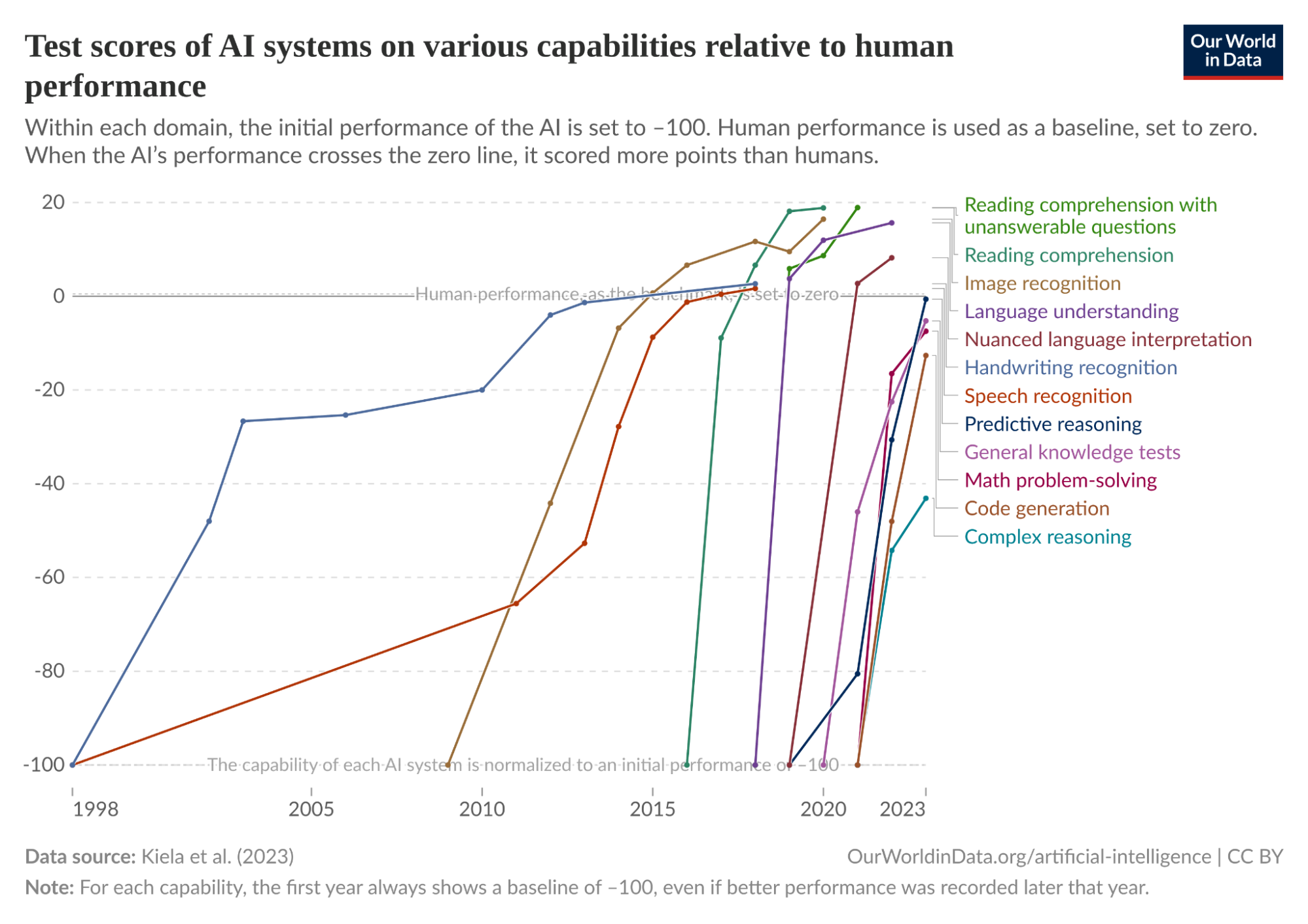

We stand at the threshold of perhaps the most profound identity crisis humanity has ever faced. As AI systems increasingly match or exceed our cognitive abilities, we’re witnessing the twilight of human intellectual supremacy—a position we’ve held unchallenged for our entire existence. This transformation won’t arrive in some distant future; it’s unfolding now, reshaping not just our economy but our very understanding of what it means to be human beings.

I get the tingling feeling at the tip of my appendix that Tyler will be right if AI progress continues at the current pace. I don’t know if it will. I’ve always been a shitty astrologer.

I often half-jokingly tell my colleagues that watching the AI chatbots do things after I give them a prompt is the closest thing I’ve seen to God. Even if development on these tools and technologies was paused at the current stage, they can still automate away vast swathes of white-collar jobs.

There’s a semantic problem with the term artificial intelligence. When people say AI, they mean everything from autonomous agents that can do anything, to self-driving cars, to Terminator-like murderous robots, to omniscient chatbots, to superintelligent systems that make humans look like glorified hunks of flesh. So ‘AI’ is a confusing term, to say the least.

Given the sheer range of tasks these technologies can already perform—or are predicted to perform—people’s imaginations run wild. AI is expected to do everything from coding, driving, and butlering to writing poetry, cooking, cleaning, cataloging libraries, teaching classes, diagnosing illnesses, advising on economics, drafting legal briefs, providing therapy, writing shitposts, ghost-writing books, giving stock tips, and even ironing clothes like an istriwala. What’s hard, at this point, is figuring out which of these futures is likeliest.

Having said that, I don’t think wildly positive or negative views are helpful. It’s important to think critically about what these technologies can do and the constraints on their development and then reason forward little by little. What’s more probable, at least in my opinion at this point, is a more measured rate of progress. But this is just a guess, not a prediction.

When making sci-fi-like predictions, people seem to ignore the real-world constraints on AI progress like limited data, regulations, talent shortages, hardware limitations, chip shortages, energy requirements, capital, and so on. Can all of this change? Of course. The question is how soon.

That doesn’t mean these AI models aren’t impressive. Two things can be true at the same time: the current AI systems can reason like humans, write amazing poetry, code, help with your finances, generate Hollywood-grade videos, pass legal and medical exams, and assist in discovering drugs. At the same time, they exhibit bizarre blind spots and logical inconsistencies. The current state of AI defies simple characterization.

Ultimately, all AI technological advancements boil down to two simple questions for normal people: Is it going to take my job first or kill me in my sleep first? Everything else is a waste of time, best left to the hyperventilating idiots on Twitter and LinkedIn.

If one looks at the available data points at the moment, there aren’t many signs of AI displacing jobs yet. The word “yet” is doing an 800-pound deadlift in the preceding sentence. All the talk about AI and job losses reminds me of Robert Solow’s famous quip: “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” It might be the case with AI as well. Things may change, but they haven’t yet. It doesn’t mean they won’t.

Or, it could simply be the case that existing employment stats aren’t catching the crisis that’s already here. Journalist and author Brian Merchant put it nicely in a recent post:

The AI jobs crisis is not the sudden displacement of millions of workers in one fell swoop—instead, it’s evident in the attrition in creative industries, the declining income of freelance artists, writers, and illustrators, and in corporations’ inclination to simply hire fewer human workers.

The AI jobs crisis is, in other words, a crisis in the nature and structure of work, more than it is about trends surfacing in the economic data. The AI boom, driven by OpenAI and Silicon Valley’s relentless talk of AGI and promotion of enterprise AI software and AI influencers enthusing over endless productivity gains, has been a powerful enabler of corporate automation and cost-cutting imperatives.

The reality is most of the stories that we hear about AI displacing jobs are anecdotal. It doesn’t mean AI isn’t replacing jobs. At the same time, it also doesn’t mean AI is replacing all jobs. It’ll be a while before we have a clear idea about the societal impact of AI.

As I was writing this post, I met an experienced lawyer who mentioned AI can almost entirely automate the creation of IPO filings, shareholder agreements, etc. He then said something scary: this grunt work is the pyramid on which the rest of the legal profession is built. David Solomon, the CEO of Goldman Sachs, said something similar recently.

The other possible reason why employment indicators aren’t flashing red is because adoption of new technologies and innovation diffusion both take time.

Discussions about the impact of AI are incomplete without the comforting assertion that technological progress destroys jobs but also creates new ones. You’ll often hear examples such as cars eliminating horse-carriage drivers while creating jobs for mechanics, factory workers, and gas-station attendants; spreadsheets eliminating bookkeepers while creating roles for more complex financial analysis; and computers eliminating typists and filing clerks while spawning entire new industries in IT, software, and data analytics.

The pattern seems clear: technology destroys jobs, but it also creates new ones. This narrative isn’t wrong, but it’s incomplete and context-dependent. It really depends on what scale you’re talking about.

All these discussions about technological shifts are at a macro level, but I’m talking about the micro level because that’s what ultimately matters to us. All those big, grand pronouncements that technological shifts always create new jobs are meaningless to individuals. It’s a bit like saying GDP always grows; however, at the same time, if GDP is going up, it doesn’t mean you will be better off. A little bit of nuance is required in thinking through these things.

When people handwavily say that ‘technology creates new jobs,’ they’re often glossing over the fact that the new jobs might pay less, require different skills, be located elsewhere, or offer less security than the ones they replaced. The aggregate statistics showing job creation tell us nothing about whether the disrupted individuals are better or worse off.

This is why the distributional effects matter so much more than the macro-level reassurances. Your personal financial planning can’t rely on the promise that ‘new jobs will be created somewhere, for someone, eventually.

History can be a useful guide in thinking about the future. However, using it deterministically to seek answers is often the wrong way. As historian Margaret MacMillan put it, and I’m paraphrasing a little, history is not an oracle that gives clear answers. What it can do instead is help us ask better questions about what’s happening in the present.

Before I talk about AI and personal finance, I want to share a little about how I think about the rise of AI. My default assumption about AI is what I call “disruption by default.” I’m operating under the assumption that these AI technologies will fundamentally reshape humanity.

What am I basing this assumption on?

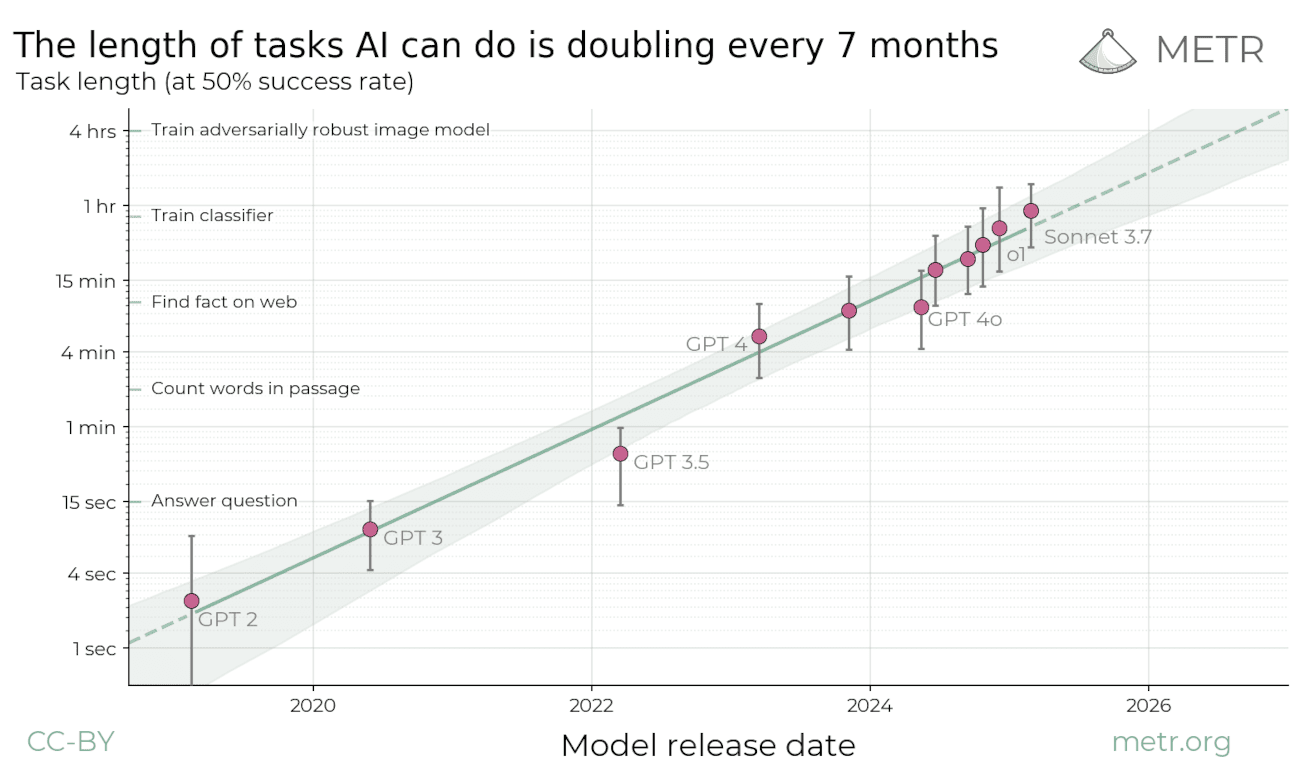

Simple linear extrapolation. I’m assuming the current rate of progress will continue.

Isn’t it hypocritical to extrapolate linearly when I said that’s a mistake just a few paragraphs ago?

At this point, you might question my stupidity, chew some paan, spit at my digital avatar on the screen, and say, “Even idiots know that progress isn’t linear.”

You might ask, what’s the basis for my linear extrapolation?

If you are expecting a sophisticated answer, I don’t have one.

We have to be honest and accept that our mental models for thinking about artificial intelligence either come from movies, sci-fi novels, futuristic predictions, or our own vivid imaginations. To say anything else would be a lie of the highest order.

I’ve been binging interviews with AI experts over the last few weeks, and the dispersion in their views is ridiculous. You can drive a fleet of Boeing 787s through that dispersion. To assume that people within the AI industry know what they are talking about would be a big mistake.

It’s important to think about the incentives of AI experts:

- Executives from big AI companies have to make grand predictions because they need a boatload of money. Pumping grand visions is the way to loosen VC purse strings.

- People in smaller AI companies have to make big predictions because they also need to raise more money. Dull visions don’t get funded!

- For academic researchers, the incentive is to get published and secure grants. Boring and incremental findings don’t get published or funded.

Looking at the predictions of economists gives you a sense of the profound uncertainty around AI:

- Nobel laureate Daron Acemoglu predicts that AI will increase US GDP by 1.1% to 1.8%.

- Economist Tyler Cowen predicts that AI will increase growth by about 0.5%.

- Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, predicts economic growth of 10%+

- Goldman Sachs predicts that AI could increase global GDP by 7%.

Who are you going to believe?

When smart people can’t agree whether we’re seeing an incremental technological change or a civilizational transformation, how can I claim to have answers? The pronouncements that AI experts make are indistinguishable from what you’d see in movies like The Matrix, Terminator, Transcendence, and Her.

Starting with the mental frame of widespread disruption has been helpful for me because it’s liberating. It’s a bit Stoic—I’m making peace with the worst-case outcome and reasoning from there. By assuming the worst, I can think about the uncertain future a little better. Or that’s what I’ve deluded myself into thinking—a useful delusion.

I would rather assume that AI will wreck my personal finances than think that AI is a fad. This is Pascal’s wager but for personal finance.

Pascal’s wager argues you should believe in God because it’s the safer bet: If God exists and you believe, you gain eternal happiness. If God exists and you don’t believe, you face eternal punishment. If God doesn’t exist, belief costs you little either way.

So believing in God is the rational choice since the potential infinite reward outweighs the small cost of belief. It treats faith as a risk-reward calculation.

This is the uncertainty around which we may have to plan our personal finances.

I want to be absolutely clear that I am saying probable—i.e., I’m making a probabilistic guess and not a deterministic prediction.

AI has exponentially increased the range of potential futures. These possible futures are also having furious sex and making more babies.

Welcome to a brave new world.

Instead of being an AI optimist or a pessimist, it’s better to hold both the possibilities in your head simultaneously. In other words, we must all be good Bayesians, start with a reasonable view of AI, actively look for evidence, and then keep updating these views.

This is the way.

“The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” ― F. Scott Fitzgerald

I’m sorry, I have no answers

The goal of this post isn’t to provide concrete answers because there are none. Anyone claiming to know exactly what AI will do to your finances is either trying to sell you something, lying, or worse yet, trying to scam you.

Instead, I have two goals:

- To stake out a thinking space I can return to as AI continues to evolve and its impacts become clearer.

- To encourage you to start thinking about AI, its impact on your finances, and the range of possibilities and choices available to you while assuming the worst.

I understand that this post might feel like a waste of time because I’m not giving you clear answers. I’m sorry about that. It would be disingenuous for me to make confident claims when we have no idea about how these technologies evolve. At best, we can make reasonable guesses.

Having said all this, I wanted to share a useful heuristic to think about AI I picked up from the economist Tyler Cowen. In a recent talk, he said that we all will have to be like dog or horse trainers trying to figure out ways to get these AI tools to do the things we want them to:

There’s some very good news here. The first is no one is really an expert. So you might think, “Oh, this is intimidating. This is terrible. There are all these geniuses out there who know this and I don’t.” But this is all so new. So you might today know zero—I doubt that’s the case, by the way—but even if you know zero today, you’re not really very much behind. You’re at the beginning of this, so you can catch up to the frontier.

I would guess if you apply yourself with two or three months of work, you’re right there doing what the top people are doing in terms of using this. You don’t need to be a computer programmer. I don’t even think that helps.

My hypothesis—this has not been tested, but having met many people, I believe this to be true—is that learning how to work with AI is like being a dog trainer or a horse trainer. It’s an alien being. You have to try to understand it. You’ll never understand it fully. Mostly, it wants to obey you, but not entirely. You have to learn how to teach the thing.

Let’s say I’m not a dog trainer, you know. My wife and I have this dog. We got it from our daughter two years ago because she had babies—the dog and the baby were a problem. So the dog was sent to us. I don’t really know the dog. The dog’s fine, the dog’s great, but I don’t know anything about dogs. So if you just brought a dog in to me here and said, “Tyler, train this dog,” I’ve got nothing. I’m an idiot.

So that’s in a way the world we’re all in. We have to learn how to train the dog. If you learn how to train the dog—call it a horse; you can’t really train a cat—so dog or horse, you can be many, many times more productive.

Tell me about the money!

Humans are not rational animals but rather extrapolating animals. When things are stable, we expect stability to continue, and when things are chaotic, we expect chaos to continue. This is why when the stock market is rising, people expect it to go to the moon, and when it’s falling, people expect it to crash to hell.

Right now with AI, we’re stuck somewhere in between—a liminal moment where we can see the sparks of the end of predictable stability of our careers, finances, and entire worldviews, and the beginning of a future that could unfold in unimaginable ways.

We often act only after something bad has already happened. This is why most people buy insurance after health issues. With AI, this tendency of ours to be lazy is unhelpful. We all need to understand what AI can do, think critically about the range of potential outcomes, map them to our specific life circumstances, and then make our choices.

Don’t wait for the shock.

Acting after the shock constrains the space of possibilities and actions you can take.

AI technologies are advancing at such a rapid clip that today and tomorrow have stopped being similar. But if there are a few things I want you to take away from this post, it’s this, in order of priority:

First: Nobody has any bloody clue what they’re talking about. You need to be okay with that.

Second: Don’t stick your head in the sand and assume these tools are just fancy autocomplete tools—that’s a mistake. It might turn out to be true that AI is just another hyped-up technology. But as someone who follows the zeitgeist, I’ve seen many people with that view in early 2022 completely change their minds by late 2022. Starting with the assumption that AI is a gimmick is a mistake.

Third: Understand how these tools work. Use them to figure out how good they are. Until you actually pay $20 to get a subscription to one of these tools and push them to the limit, you’ll never understand what you’re competing against. This post is an amazing place to start.

Fourth: Extreme views might not be helpful. It’s easy to think about extreme positions both on the optimistic and pessimistic sides. I’d rather take the middle path by using these tools regularly, following the technological progress, and updating my priors.

Finally: The simple fact is we don’t know how to plan our personal finances based on AI’s impact. But if this question of “What will be the impact of AI on my personal finances?” doesn’t remain active in your head, then you will be in for a rude shock later. It’s better to keep this question open in your mind rather than looking for concrete answers when there are none.

Despite all this seeming like doom and gloom, I think the traditional personal finance tools are still useful. It’s just that they have to be paired with a deep sense of curiosity and intellectual humility about the future that is to come.

All the traditional financial tools that we use to manage risk like precautionary savings, alternative income streams, making cost-of-living adjustments, visualizing the worst and planning for it, having adequate insurance are still useful. It’s just that one shouldn’t overestimate their utility in thinking and adjusting to this seemingly massive adjustment on the horizon.

The financial guidance in this post is deliberately light because it reflects the genuine uncertainty inherent in thinking about the world after AI. Providing specific tips would be unethical of me.

That said, AI progress will ultimately either have a good or a bad impact on your personal finances. What Finance 101 teaches us is that when outcomes are certain, you can take more risk, but when things are uncertain, you need to increase your financial defenses.

This means:

- Higher precautionary savings in the form of a larger emergency fund, more savings, and more investments.

- Adequate life and health insurance. This is critical.

- Contingency plans to reduce living expenses if needed. Have a Plan B, C and D.

- Figure out ways to monetize your human capital or earnings potential through reskilling, alternative careers, or new income streams.

When facing this level of uncertainty, the logical thing to do is not to try and predict specific outcomes but to build large financial buffers to survive a range of potential negative scenarios.

The AI-shaped hole isn’t just about technology—it’s about the collapse of the certainty that our financial plans have always relied on. We’re all grappling in the dark now. The question isn’t how to fill that hole, but how to plan around it.

Perhaps the most honest approach is to accept that we’re planning for multiple possible futures simultaneously, staying alert rather than comfortable and adaptable rather than optimized. In a world where the rules might change faster than we can learn them, maybe the best financial strategy is learning to be comfortable with fundamental uncertainty.

Because ready or not, the future is already here. It’s just not evenly distributed yet.

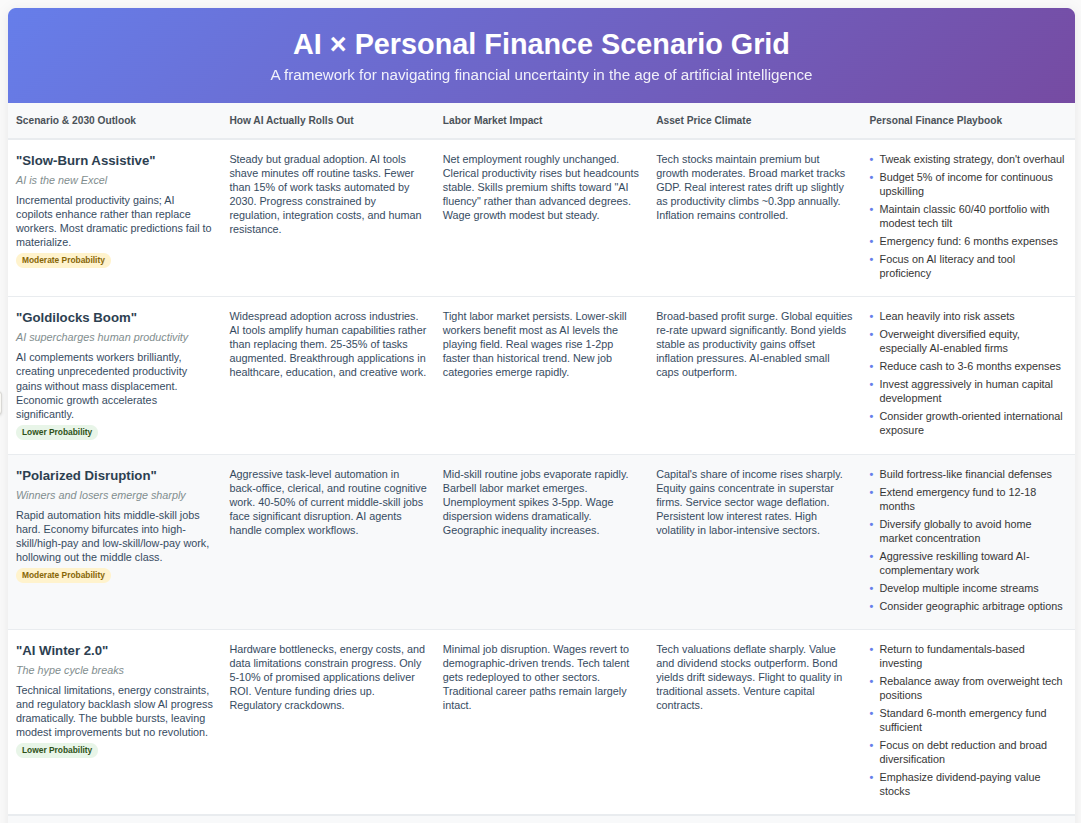

Considering all of this is about AI, here’s a scenario grid and checklist that Claude/ChatGPT gave me to prepare 🥲

i am really worried about my current and future situation.

Graduated in 2022 but yet no success in tech entry. After trying hard in govt job exams for 2 year. Last year i got into coding from a offline bootcamp because they tech and make placements like college do.

This is the only hope but Ai is like a bother who wants every share of my portion. Right now i am doing MERN stack for Frontend and fullstack web development but now realising Java full stack combination is relatively more secure than others.

The lowest entry pay is like 8-9k upto 20k, average 11-13k.

I can never dream about buying own home in near future, currently planning to buy a bike for travelling and in case the company layoff me then to survive the bike EMI on Zomato or Blinkit. Best bike is Honda Sp 125. Perhaps my knee ACL ligament reconstruction surgery, right now doctor wants 2L , so in 2 years it would be like 3-4L with 9m rehab. I could go trekking or sprinting in confidence, who knows.

Tech is field highly saturated and stabilizing from the boom. Companies want star performer now , average won’t cut it. I don’t think average fresher without sending 1-3k resume would land a job.

With the pace of sprinting inflation after 2019 .

Let’s see what Life surprise life has got for me !

Savings? marriage? healthcare? home?

hahahahahahaha……..

Hey bhuvan,

Good article but honestly, it did not provide any insight on how AI will assist in personal finance domain. The words, expressions, visions, views, paraphrases are all imaginations (ofcouse imaginations are the projections of past experience/data) rather than the actual meaning I wanted to fetch from this post.

Anyways, good luck !!