We’re poor, but we ain’t broke

Humanity, to Noah Smith, is caught in a never-ending war against poverty, ‘the elemental foe’:

Humanity is at war — a war so old, so terrible, and so all-consuming that even World War 3 would be a minor skirmish in comparison. Whether or not we remember it, we are always on death ground. But our intelligence has given us an opportunity not afforded to other animals — the chance to conceive of our species as a single team, fighting not individually but as an army united against the implacable, elemental foe of poverty and desolation.

It is our highest task to push that foe ever backward, to build out the fortress of industrial modernity, to reclaim the Earth for the safety and comfort of beings that think and feel.

If humanity is at war with poverty, India is the bloodiest battleground.

Source: The Statesman

India emerged into independence in 1947 as a hollowed, tortured, starving land-mass; simultaneously one of the poorest and one of the most populous countries in the world. In the last half-century of British rule, we had seen plague and famine at biblical scales. One of the worst mass-starvations in history was a recent memory. Only five years ago, the people of Bengal were reduced to eating grass like cattle — not because it was nutritious, but because it took up the empty space in their stomachs.

The country was broke. The people were broke. The government was broke. In those early days, people lived on the mere dream that a free nation could change their fates. When the harvest was good, 65% of the country lived under poverty. When it was bad, we simply didn’t know how to measure how bad things were.

Mass starvation was always a failed monsoon away. Hunger had become an intractable problem. We made it through, somehow, eating wheat of a quality “fit enough only for pigs” received in charity from the United States. India was constantly on the brink. A single shock could become a humanitarian crisis. In 1965, when war broke out, Prime Minister Shastri publicly pleaded with the entire country to sacrifice one meal a week, if not more. It was only after the Green Revolution began, in 1967, that we learnt how to grow enough food to feed ourselves.

Source: The Hindu Businessline

Poverty dropped to around 40% in the 1960s. But then, it refused to budge any lower. Decades of social welfare programs couldn’t bring it down, nor could a famous ‘garibi hatao’ program. Instead, India simply learnt to cope with its stubborn poverty. Its ‘Public Distribution System,’ initially built to tide over World War II-era food shortages, became an evergreen feature of the Indian state, keeping the country alive, even if on the ventilator. By 1994, poverty was still at ~35%. It was only then, after four-and–a-half decades of penury, that our economic condition finally started to improve.

All of this is to tell you why you should be deeply proud that, according to the data for 2022-23, India has nearly eliminated absolute poverty.

What is poverty, round one: The numbers

Where do we draw the line?

How poor are we as a country?

To answer that, you first need to ask: what does it mean to be poor? Not having enough money? Sure. But nobody ever thinks they have enough money. Here’s what the World Bank says:

To be poor is to be hungry, to lack shelter and clothing, to be sick and not cared for, to be illiterate and not schooled. But for poor people, living in poverty is more than this. Poor people are particularly vulnerable to adverse events outside their control. They are often treated badly by the institutions of state and society and excluded from voice and power in those institutions.

Is it gut-wrenching? Yes. Does it help you figure out if someone’s poor? Not exactly.

Well, if one has no food or clothing at all, or lives on the street, they’re definitely poor. But what if they have some food, and some clothes, and have a place to stay, even if it isn’t very pleasant? What if they’re entitled to basic schooling and healthcare, but it’s all ten kilometres away and the quality is terrible? At what point do we draw the line and say: hey, you have enough now that we no longer think you’re poor?

There are many such lines, it turns out.

The World Bank has an ‘extreme poverty’ line: you’re extremely poor if you live on less than $2.15 (on a purchasing power parity basis) per day, on 2017 prices. That is, what you spend on an average day buys you less stuff than what an American could buy for $2.15 back in 2017. (Previously, the World Bank had drawn this line at $1.9 a day at 2011 prices. You might see references to that number as well, later in this post.) Right now, that’s roughly ₹65 a day.

India also uses its own ‘Tendulkar Line’, which comes close. In prices from 2004-5, you’d be poor if you lived on less than ₹447 a month in villages, and ₹579 in cities. Factoring in inflation, today, that’s around ₹1,630 in villages and ₹2,000 in cities.

Source: Wikimedia

Some lines are more ambitious. Aside from the Tendulkar line, we also have the ‘Rangarajan Line’: which, today, comes to around ₹1,940 in villages, and ₹2,820 in cities. Similarly, the World Bank, apart from defining ‘extreme poverty’, asks lower-middle income countries to judge themselves against a higher bar — a higher poverty line of $3.2 (again, adjusted for purchasing power parity), at 2011 prices.

If you want to know how poor India is, you need to know which line to point to.

At long last, data!

Once you’ve chosen the line you want to look at, though, it’s still hard to know how poor India really is. That’s a really tough puzzle to crack, honestly: you need to guess at how 1.4 billion different people live, after all.

If you want to be in the right ball-park, you need to collect gargantuan amounts of data, fit it into elaborate models, and then make assumptions which may or may not be justified. No matter how careful you are, you can make many different kinds of mistakes, which is why such exercises are extremely controversial. If you have the time to get into it, this is a great place to look.

For a long time, though, everyone’s biggest complaint was that we simply had no data at all. A good place to look for data is the ‘Household Consumption Expenditure Survey’ (HCES), which the government is supposed to conduct every five years. Only, no survey results had been released for more than a decade. Not because there was no survey, mind you — the government did collect the data in 2017-18; it just didn’t release any. We’re not sure why, but it might be because it contained a lot of bad news. (The government pointed to ‘data quality issues’, for its part.)

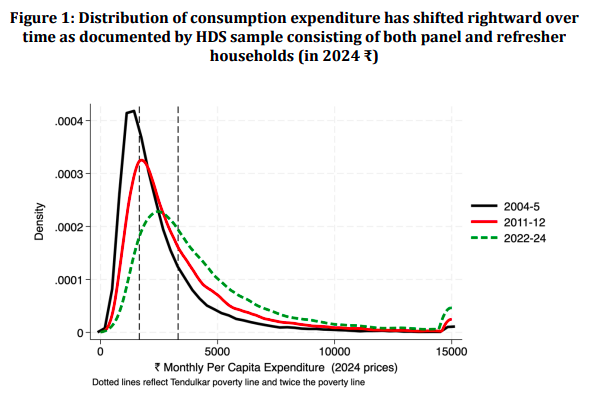

Now, though, we have new numbers. The government conducted another HCES in 2022 and 2023. This time around, the results were released. If early analyses are to be believed, what the survey says is astonishing. (though you should add salt to taste.) At some point in the last decade, we’ve practically eliminated extreme poverty.

The best news we’ve ever heard

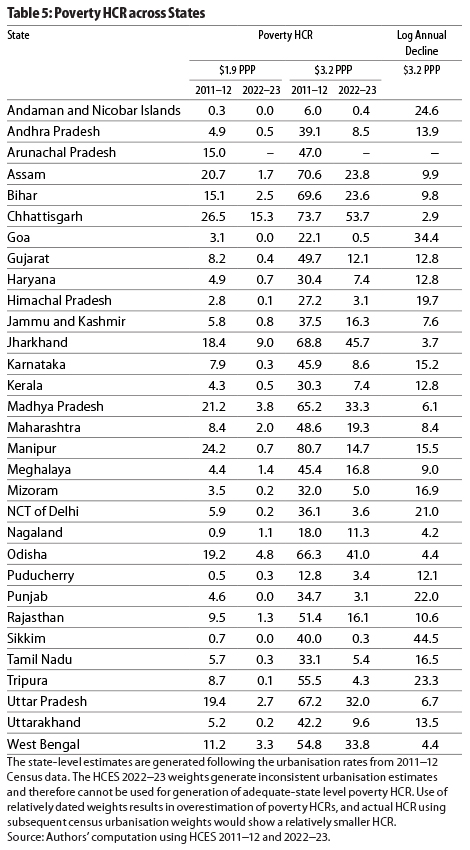

For the first time since we started collecting data (and perhaps for the first time in our history), almost all of India — more than 97% of our population — is above both the World Bank’s ‘extreme poverty’ line and the Tendulkar line.

In most states of India, extreme poverty is practically absent.

Across the board, Indians are consuming more than they did before.

How did we get here? For one, liberalisation just made our economy much, much larger. But the government has played its part as well.

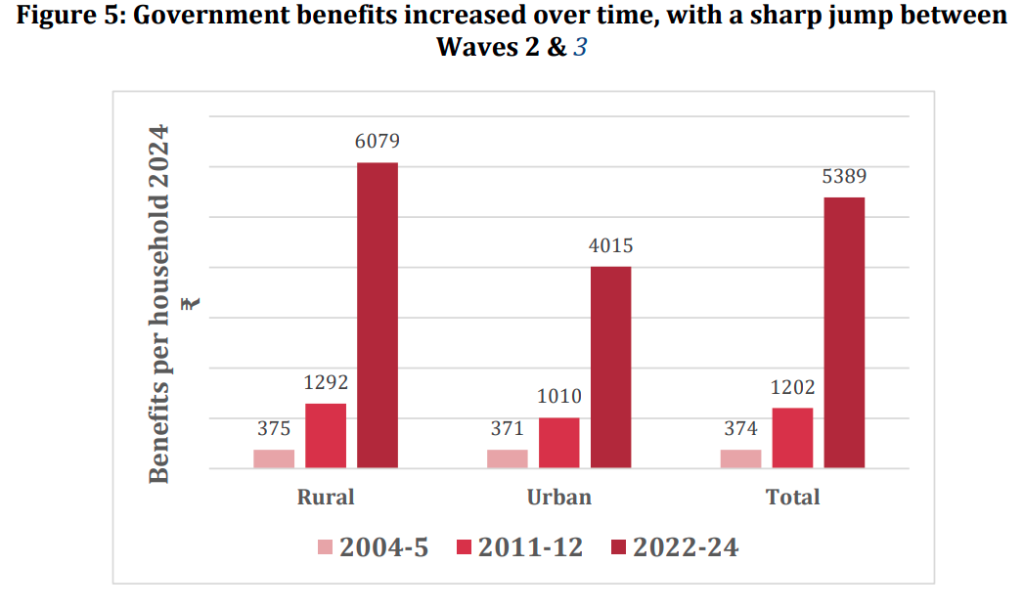

For all its flaws, the Indian government has waged a genuinely valiant campaign against poverty. Whatever else you may think of subsidies and welfare, it’s clear that the government’s many schemes — free grain, free housing, free piped water, free cooking gas, free toilet construction, and more — have made an actual difference in people’s lives. Our recent successes coincide quite neatly with a massive uptick in the government benefits people receive:

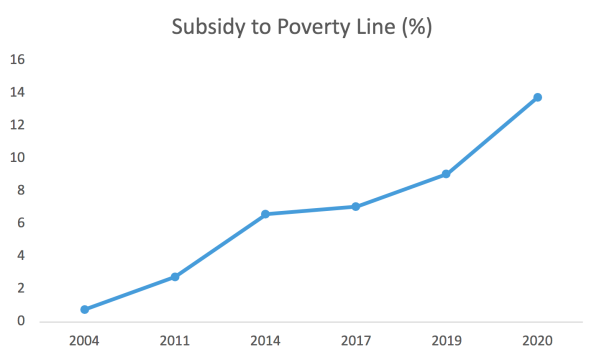

In fact, the subsidies the poor receive account for more and more of what they need.

Let’s not overstate what has happened. There are many Indians who still live just above the ‘extreme poverty’ line. Their lives are, for all practical purposes, just as desperate as the ‘extremely poor’. They’re at constant risk of falling back under the poverty line. India is still one of the poorest places in the world; a large part of our country still resembles Sub-Saharan Africa.

With all those caveats in place, though: in the last eleven years, we’ve done more to reduce poverty than in the thirty years that came before. This is, make no mistake, one of the most dramatic reductions of poverty the world has ever seen.

What is poverty, round two: Our poverty hits different

Is there more than one way of being poor?

Of every six ‘extremely poor’ people in 2011, roughly speaking, five have clawed their way out of poverty by now. That is remarkable in itself. But it’s not as though only their lives that have changed. When an economy goes through such a big change, the lives of everyone are affected.

Over time, there’s been a big shift in why people are poor. To understand that, though, we need to go back to our original question: what does it mean to be poor?

Consider two people:

- Manish, 27, works the night-shift in a boutique hotel in West Delhi. His father was a small-time entrepreneur with a string of failed businesses, but he made enough to put Manish through a half-decent English-medium education. All seemed well, in fact, until Manish’s mother contracted cancer and died after a bitter, year-long struggle — leaving him heartbroken and severely in debt. His net worth is negative ₹1,14,000.

- Meena, 31, is a mother of two children, who lives a few kilometers down the Ganga from Begusarai, Bihar. She was born into a community of leather-workers, and was the first in her family to step inside school — although she dropped out a few months into the third standard. Her husband works in Ludhiana, but hasn’t sent money back home in months. She’s borrowing to survive. Her net worth is negative ₹48,000.

Objectively, who’s poorer between the two? Easy: Manish. His net worth is way lower. Whose situation looks more hopeless, though?

That’s a harder question, isn’t it?

Things look bad for Manish. He needs to get back on his feet, shake off the pain of losing his mother, and work his way through his debt, bit-by-bit, until it finally disappears. It’ll probably take him years before he feels financially secure.

But things are desperate for Meena. Her problem isn’t simply that she’s in debt today. It’s that she’s sinking deeper into debt every day, and it feels like there’s nothing she can do. Without a flash of good luck, it’s unclear how she’ll ever break out.

Why are people growing poor?

There are two reasons someone might be poor: accidents of birth, and accidents of life:

- You could be cursed with an ‘accident of birth’ from the very beginning. Maybe you’re born in a place that has no real economy. Perhaps you simply never went to school, and never learnt any skills that could earn you money. Maybe you were born into a caste, gender or religion that cuts you off any opportunities around you. These ‘accidents of birth’ can keep you in chronic poverty, with no real way of getting out.

- Life might not be too bad until some event — an ‘accident of life’ — pushes you down. You might get laid off, or fall horribly sick, or have a bad accident, or lose a bread-winning member of your family. A relative’s wedding may unexpectedly go way over budget, or you may have an unplanned child you can’t afford. These circumstances can push you into poverty. But, often, ‘accidents of life’ aren’t permanent. You may suffer from transient poverty; once things are better, you might still get back on your feet.

In a stagnant economy, people find it hard to improve their lot in life. If you’re born with major disadvantages, overcoming them is simply too big a challenge. Most never manage to break out. Poverty, then, usually comes from ‘accidents of birth’. If you’re poor, it’s most probably because you never had a chance to be anything else.

In a booming economy, though, opportunities to escape poverty keep popping up. Many people latch on to these opportunities and drag themselves out, overcoming the accidents of their birth. Karma, however, is still a b!tch in the best of times. Terrible things keep happening, pushing people into poverty. Most of this poverty, though, is transient. There’s a constant churn at the edge of the poverty line, with people constantly falling in and out.

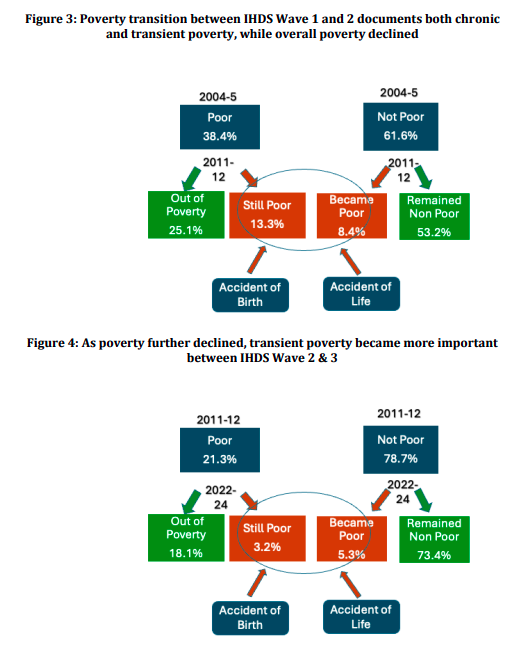

Over the last twenty years, India has seen its poverty morph, from chronic to transient:

As many ‘chronically poor’ Indians make their way out, most poor Indians today — 62%, in fact — are poor because of the accidents of their life. They’ve ‘fallen’ into poverty. If things go well, they might get out again.

Why does this matter, though?

Understanding this shift should shape how we think about poverty as a country.

For one, the transient poor pose a measurement problem. All poor people don’t live the same way. If you’re poor because of an accident of your birth — if you were born poor; if your parents were poor, as was most of your family — poverty is probably baked into your lifestyle. Where you stay, what you eat, what you wear, all of it probably reflects your circumstances. You’ve simply never learnt to live any other way.

On the other hand, if you’ve fallen into poverty, that might not be readily obvious from how you live. It’s hard to change your lifestyle as fast as your financial situation. Research shows that most people calibrate their lifestyles to match their long-term incomes. In the meanwhile, you might borrow to make it through, or you might take unacceptable risks to put money together, but you probably won’t live like someone that’s always been poor.

This is a problem, because we use consumption data to understand who’s poor. If you’re poor but spend like someone that isn’t, the data won’t tell us the difference. It’ll simply say you’re not poor. We have no way of peering behind the numbers to see if your spending is sustainable, or if you’re flailing desperately to make ends meet. Because of this, there’s a good chance we aren’t catching a lot of India’s poverty.

There’s also a bigger problem — a policy problem. The challenge with a good policy is that as soon as it is successful, it becomes outdated. Despite our successes, we’re increasingly doing the wrong things.

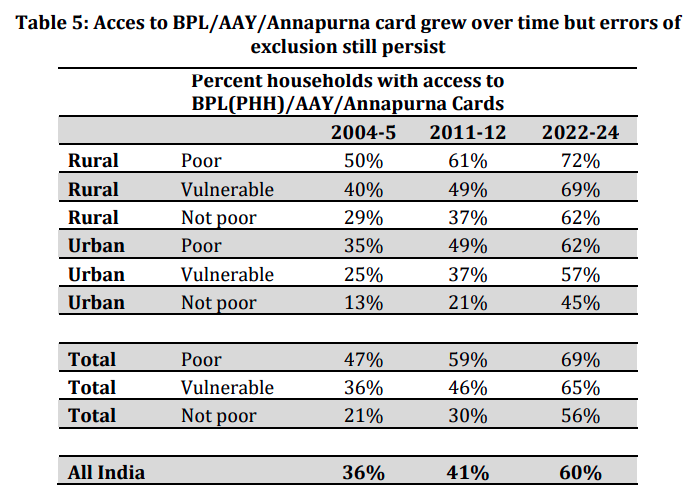

Traditionally, we’ve tried to find specific poor households (you might have heard of ‘BPL’ cards, for instance), and send benefits their way. Sounds great in theory. Only, this requires you to go to every single household in India and see how poor they are. This costs money and time. We’ve done it before, through the ‘Socio Economic and Caste Censuses’ we’re supposed to have every decade. Only, the last one happened in 2011.

Think about it: we don’t know who’s poor today. We only know who was poor thirteen years ago. That’s what we’re basing all our schemes on. This could have worked in an India where the same people stayed poor for decades. But in a more dynamic country, where people keep shifting in and out of poverty, our approach is meaningless. There’s basically little connection left between the people who are actually poor, and who our government designates as poor.

We need to change our approach. We need to stop people from falling into poverty, rather than pulling them out of it. For the first time in generations, most Indians actually have something to lose. Our fight against poverty is no longer one of simply giving things to people who don’t have any. We now need to insulate people from the shocks of life, rather than merely compensating them for the circumstances of their birth. Insurance, retirement plans, unemployment benefits, healthcare, end-of-life care — as India transitions, this is the new anti-poverty armoury we’ll have to move to.

What is poverty, round three: Whose line is it anyway?

The poverty line is a national contract

So, we have a poverty line, and most of India has climbed above it. Does that mean Indians are no longer poor? Of course not; that’s absurd. Then what does it mean?

For that, we need to return to our old question: what does it mean to be poor?

Poverty is relative. There are poor Indians, sure; but there are also poor Americans, and poor Swedes, and poor Japanese. It hardly matters that the circumstances of all their lives are very different. It hardly matters that most poor Americans live like upper middle-class Indians. All these people are ‘poor’ because they are poor compared to those around them.

See, there are two purposes a poverty line serves:

- Monitoring: A poverty line is a point of reference. Over time, it tells you about how society is changing. When you pick a line and see how people move against it over time, you learn about how people’s living conditions are changing.

- Norm-setting: At the same time, a poverty line is also a social contract. In picking one, a nation basically says: “Here is where we, as a polity, make our last stand. This is the lowest quality of life we consider acceptable. If anyone falls below this, we consider it our moral responsibility to pull them out.”

As people make their way past the poverty line we’re looking at — the Tendulkar line, for instance — it’s no longer a helpful point of reference. There’s simply nothing underneath it to measure.

Then, does it still serve a normative purpose? Is this where we make our last stand?

Is this the right line?

India drew its Tendulkar line at a point where people can barely subsist. It was calculated to allow people a diet of about 1800 calories a day (at least in cities), along with some limited spending on health and education. Below this, one would scrounge through an animal-like existence, barely subsisting, at the very brink of starvation. The Tendulkar line hovers around athe World Bank’s extreme poverty line — what the world considers the absolute floor for human living conditions.

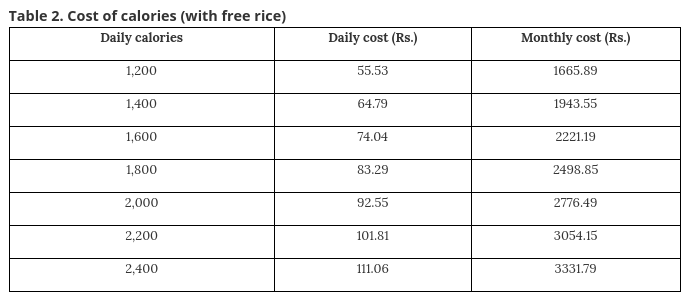

It barely manages to ensure even that much, in fact. If you take a standard meal of daal, rice, bhindi and some onion, this is what it would cost every month:

At the Tendulkar line, today, you’re essentially inching slowly towards starvation.

(Bhindi is the most expensive part of Ghatak’s and Kumar’s hypothetical ‘meal’, making up more than 40% of the cost of the plate. Without it, you’d probably get more calories for cheap. But then, you have to ask yourself: are we the sort of nation that considers bhindi a luxury item?)

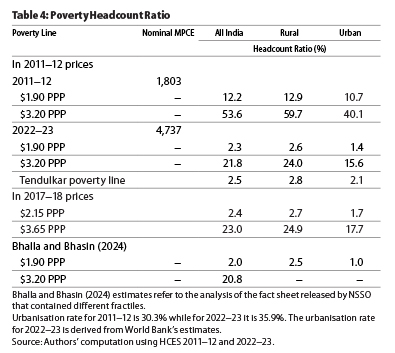

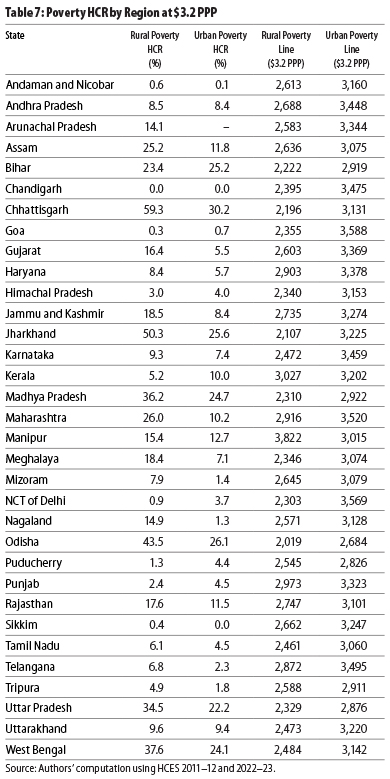

If our current poverty line doesn’t help us measure much of anything any more, and points to a life at the very edge of human dignity, perhaps it’s time for a new national social contract. A better reference point, perhaps, is the World Bank’s suggested poverty line for lower middle-income countries: $3.2 per person per day, at 2011 prices. At this updated line, this is how Indian poverty looks:

Here, we still look very poor. This doesn’t feel nearly as nice as low single-digit poverty figures. But reality stays the same; we’re just measuring different things. We don’t grow poorer by setting the bar higher. We just show more self-respect as a country.

We can now afford to aim higher

Fighting poverty is perhaps humanity’s oldest goal. I have no idea what our earliest genetically human African ancestors cared for, but I’m sure of one thing: they hoped that everyone in their tribe had enough to eat. We’re finally there.

To return to Noah Smith again:

… Poverty is the default condition, not just of humanity but of the entire Universe. If humanity simply doesn’t build anything — farms, granaries, houses, water treatment systems, electric power stations — we will exist at the level of wild animals. This is simply physics.

Look at pictures of the other planets in the solar system — sterile desolate rocks and poison gases baked by radiation. That is the natural state of most planets. Then look at animal existence in the wild places of the world — a constant desperate struggle for survival, where populations are kept in equilibrium only by starvation and predation. That is the natural state of most life. Then look at how humans lived for the vast majority of our history — indigent subsistence farmers forever skating on the rim of famine. That is the natural state of preindustrial humanity.

Poverty is the rule; wealth is the exception.

This is the first time in our history that we have beaten absolute poverty. This is the richest India has ever been. It’s nice to imagine that we were once infinitely richer; that our ancestors lived like the Americans or Singaporeans of today. Unfortunately, that’s just never been true.

Source: Wikimedia

Yes, India was once relatively wealthy. And today, it is relatively poor. In absolute terms, though, most Indians have always been impoverished. Even before the British arrived, when India made up a quarter of the world’s economy, roughly one-fifth of India lived in absolute poverty. Our mental picture of our past — ornate palaces and temples, manicured gardens, people decked in gold from head-to-toe — has little to do with how ordinary people have lived at any point in our history. Much like how pictures of the Ambani wedding bear no resemblance to my sewage-stained 2BHK in interior Bengaluru.

But think of what this means for our moment in time.

We are the first generation ever to see an India where absolute poverty isn’t the norm. From the first hunter-gatherers that found their way into the subcontinent sixty-five thousand years ago; through wave after wave of migration; through the rise and fall of the Indus valley; through the Kushans, the Mauryas, the Guptas, the Cholas, the Mughals: through all of history, recorded and unrecorded, there is only one generation where almost nobody in this land lives a desperate, animal-like existence. And you, dear reader, are a part of it. You are living through a civilisational achievement.

All this means, though, is that we can finally join the rest of the world in aiming higher.

References

Look, I’m an idiot. I just read what other people say and then vomit it out, because internet ink is free. Don’t trust me; go to the experts. Here is everyone I borrowed from to write this piece:

- Bhalla & Bhasin, India eliminates extreme poverty

- Bhalla & Bhasin, Poverty in India over the Last Decade

- Bhalla et al., Raising the standard: Time for a higher poverty line in India

- Bansal et al., Inferences on Consumption Inequality and Poverty Headcounts

- Desai et al., Rethinking Social Safety Nets in a Changing Society

- Ghatak & Kumar, Determining how many Indians are poor today

- Rangarajan & Dev, With new consumption survey, the need for new indices

- Srinivasan, Poverty Lines in India: Reflections after the Patna Conference

- Subramanian, The Household Consumption Expenditure Survey 2022-23

Hmm.. the headline is misleading. Because you don’t say what you mean by absolute broke. Perhaps it should say “we are poor, but not spending the whole day on the brink of starvation trying to survive like animals in the wild”. From one pov, I guess it’s something to celebrate— the civilisational moment where we have graduated from wild animal state — but that seems to be an unacceptably low bar.

I appreciate you for getting together the different data points and giving an overall context. It would have been good if the implication of living on the edge of the poverty line had been explored a little more.

A very good article, on the whole, except that the start and either end do not represent the body.

Thanks for writing in, Veda!

”Not spending the whole day on the brink of starvation trying to survive like animals in the wild” is a fair characterisation for what I meant by ’broke’. I do still think this is something worth celebrating, though, because of how incredibly hard it is to even achieve this low bar.

It’s a tragedy that all achievements feel banal once you’re there. Human progress is a treadmill. There’s no finish line. Our world would have felt like a utopia to most people in history. Now that we’re here, we’re all just jaded and vaguely grumpy all the time. As we will be, indefinitely. Anything that feels utopian to us, today, will seem unexceptional to whoever lives there.

Which is why, in my view, it’s worth taking a moment to savour this point in time, even as we set our sights higher. The beginning and the end aren’t meant to represent the body, they’re to ground it in the fact that we’re capable of great things. 🙂