China’s Unreal Estate

This post is the third and final part of our series ‘Big Trouble in Brittle China’, which covers the many problems that are visiting the Chinese economy today. Click here for part one and here for part two, where we lay the context for China’s forays into real estate.

To recap:

For decades, China experienced a sort of economic growth the world has perhaps never seen. It did so through investment at an unprecedented scale – which it used to build a towering modern economy from nothing.

Its manufacturing industry was an early beneficiary of this investment, and it made China the factory to the world. It still is, with a third of global production concentrated in the country. But disaster struck in 2008, when the Global Financial Crisis forced people in the developed world to consume less. Exports, suddenly, were no longer a reliable source of growth. Despite being a manufacturing superpower, manufacturing alone could not create the level of growth that China desired.

As China grew richer, its own population – more than a billion people – should have emerged as an alternative to other advanced economies. But that never came to be. The country had diverted too much money away from its people and into its economy. The people saved whatever money came to them. They simply didn’t spend like others did.

China needed a new engine of growth. It found one in real estate.

Five: Real Estate

Although Chinese consumers spend relatively little compared to their global peers, there was one thing they would spend on freely: property. It was where they would put their abnormally high savings. A home was a place to stay, an investment and a marker of social status – all rolled in one. To young adults struggling with a fiercely competitive marriage market, a home was also a crucial advantage. A house, it seemed, was worth any amount of money. China, as a result, has one of the highest home-ownership rates in the world, with almost 90% of all Chinese families owning their own home.

The government, too, played its part. The real estate sector’s growth was shepherded by the People’s Bank of China, which ensured that sufficient money was made available to it. Meanwhile, local governments sought out real estate projects for the revenue windfalls they could generate. Chinese local governments don’t usually charge regular taxes on housing property. Instead, most of their revenue comes from leasing land to property developers. Local functionaries often get a cut of these leasing deals under the table. Because of this, towns and cities across the country were courting new development projects.

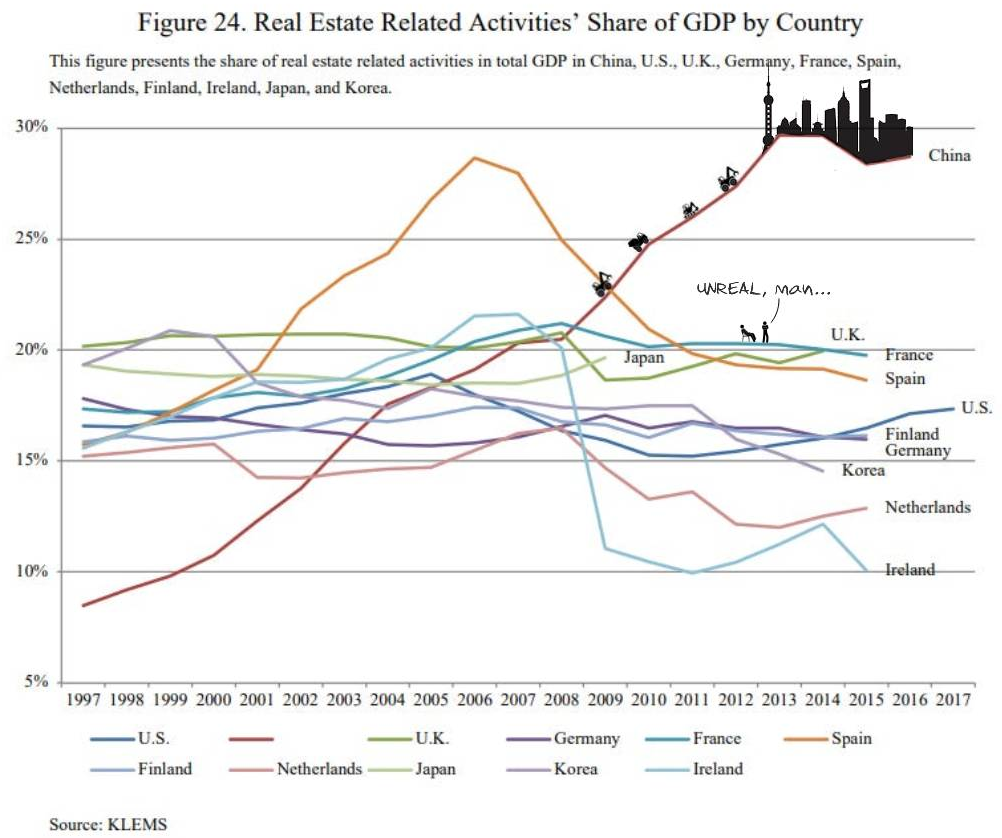

Real estate became the perfect business. It allowed you cheap credit, state patronage, an unlimited supply of customers, and a near-guarantee that prices would keep rising. Over time, the industry grew to almost a third of China’s economy: making Chinese real estate the most valuable industrial sector in the world.

Chart by Rogoff & Yang, NBER (link), defaced by us.

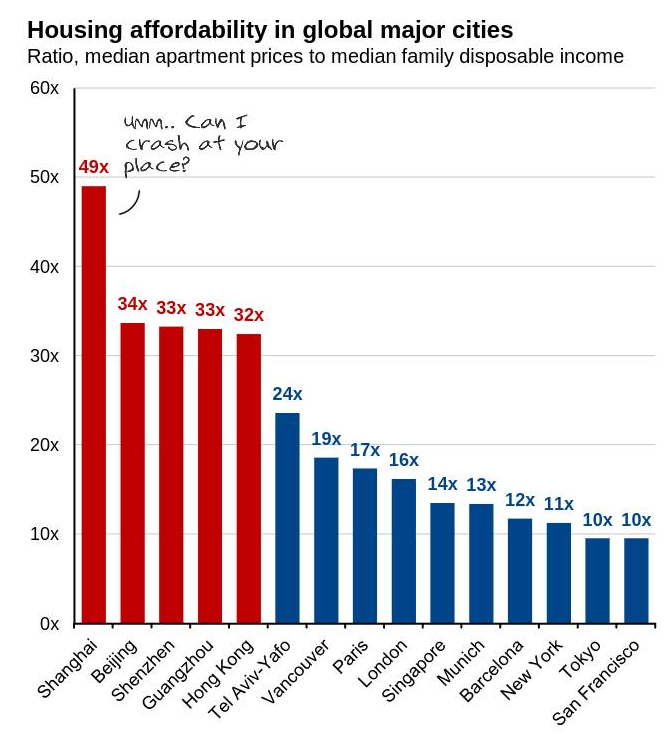

Eventually, though, even a booming industry couldn’t keep pace with demand. As migrants flooded China’s rapidly expanding mega-cities, they pushed up home prices. New age industries created a class of ‘super-earners’ that drove prices up for everyone else. Investors began scooping up any houses available on the market – a fifth of which they left vacant. Moreover, the government was auctioning land at ever higher prices, which reflected in what developers then charged customers. House prices have rallied almost steadily since 2003 – save for a few temporary blips – to a point where all the money one earnt over an entire lifetime couldn’t buy one a home.

Chart by JP Morgan (link), defaced by us.

The Chinese Government would occasionally take measures to combat such increases in prices – indirectly, by limiting the home loans one was eligible for, and directly, by fixing prices. But there are always ways to work around regulations. Informal social networks cropped up to collectively put up the funding one needed to buy a home. And people simply refused to follow government-fixed prices.

In fact, many rejoiced in the perpetually rising prices of Chinese homes. Owning a house, for Chinese society, looked like a sure-shot means of wealth accumulation. But although they couldn’t see it, these high prices were hiding something dark.

Six: The investments stop paying off

After decades of incredible, unprecedented growth, something had shifted in the Chinese economy. Real estate was beginning to look like a viable alternative to investing in the real economy. Even those outside the sector were getting into the game. Manufacturing firms, for instance, had started making real estate investments that bore no relationship to their core business.

What had happened was that the economy could not, for the moment, absorb more investment. The low-hanging fruit had been plucked. Finance, moreover, was actively being routed to a few firms in sectors that China had selected under its industrial policy. Meanwhile, property prices kept rising. To many people, it seemed far more profitable to speculate on real estate than to earn money the tired old way – of working hard to make new things and selling them for a profit. Banks, too, considered it much more safe to lend to real estate projects than to anything else.

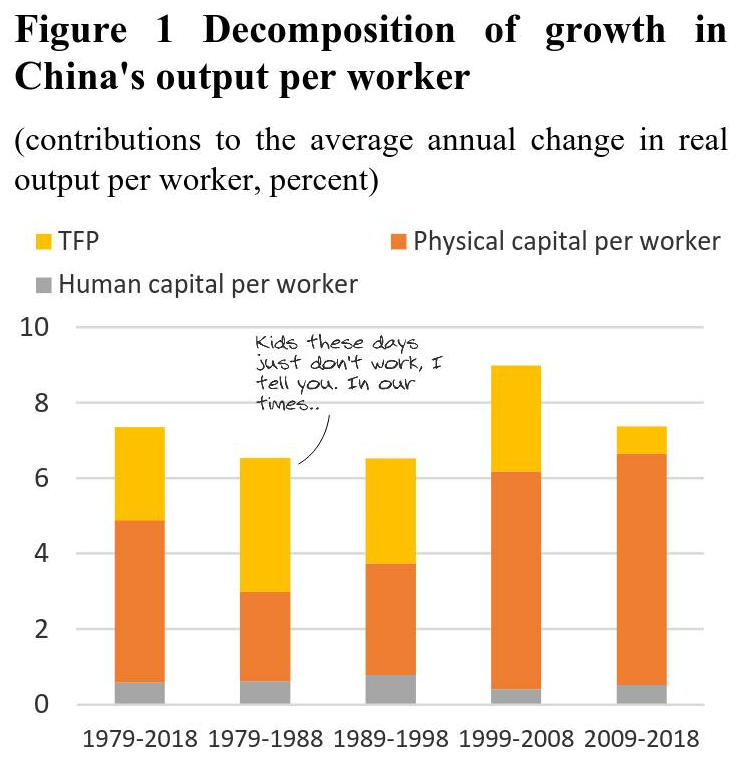

For a growing portion of the Chinese economy, earning money was slowly becoming less about doing useful work, and more about finding the right bet to take. Productivity growth dropped. The economy stopped creating value the way it once did. Economic output became a simple matter of spending a lot of resources and eking out an upside.

Chart by World Bank (link), defaced by us.

This is a problem. Countries generally advance by pushing up their productivity, as they learn to squeeze more out of the people and resources at their disposal. If anything, China needs this more than others. Its population is rapidly growing older, and many may soon be in no position to work. The others, the workers that remain will have to provide for the entire economy, for which they will have to get to very high levels of productivity. Unfortunately, China does not appear to be taking this path.

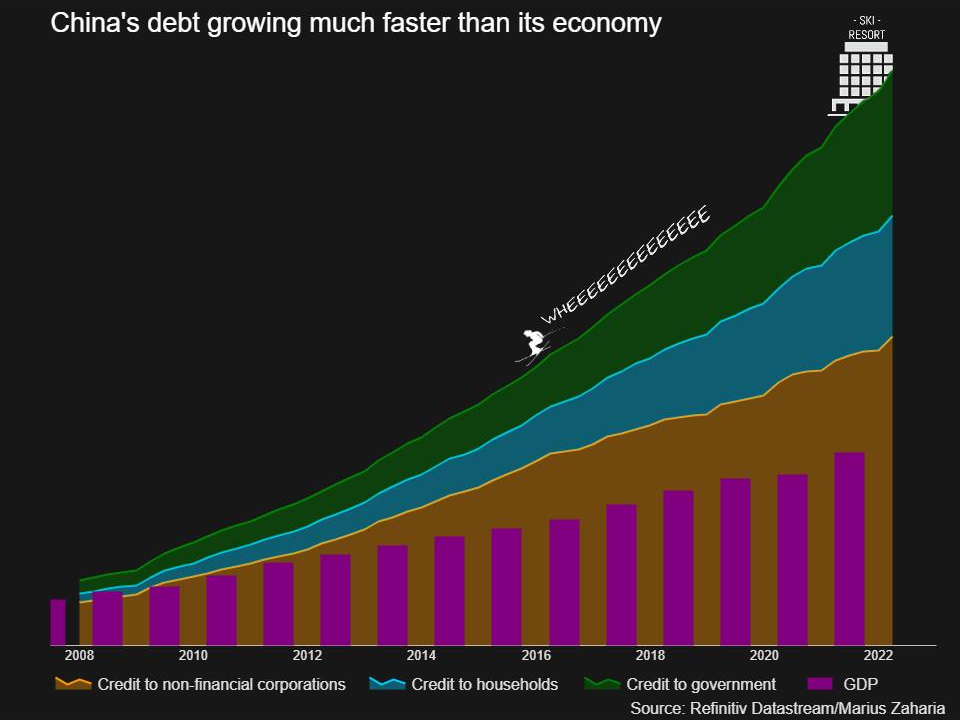

The amount of money being poured into the economy, nevertheless, has remained astounding. It kept China’s GDP growing at a brisk pace. This money was borrowed, as it had always been. But every year, that borrowed money gave less bang for the buck. The country’s GDP simply wasn’t keeping pace with the debt it was taking on.

Soon, its debt burden grew to thrice the size of its economy. Worse still, a lot of additional debt – particularly that taken by local governments – remains hidden under fancy accounting trickery.

Chart by Reuters (link), defaced by us.

This has happened before. Countries like Spain and Japan have seen severe property bubbles fueled by debt, which, when they burst, hurt their growth prospects for years. This was something China was desperate to avoid. And so, it took measures. They were perhaps a little too abrupt.

Seven: The Government hits the reset button

In 2020, the Chinese government put down “three red lines”. One, the total liabilities of a builder could not cross 70% of their assets. Two, the total debt of a builder could not cross their total equity. Three, the builder’s short-term debt could not cross the cash they held. Companies would be graded by their performance on these metrics. Their performance would decide the amount of money they could borrow.

Chinese real estate companies had, to this point, lived on debt. They thought prices could never fall, and so, they borrowed and built far more than they had demand for. When these criteria came into force, they pulled the carpet from right under these companies’ feet. Two thirds of China’s 50 largest builders defaulted on their debts. Bond markets crashed, with debts of US$ 65 billion being left unpaid. Evergrande, the most valuable real estate company in the world until recently, became the poster-child for this collapse, falling head-first into a long and painful liquidation. Many others have only avoided bankruptcy by a whisker, in part because Chinese banks aren’t recognising bad loans just yet.

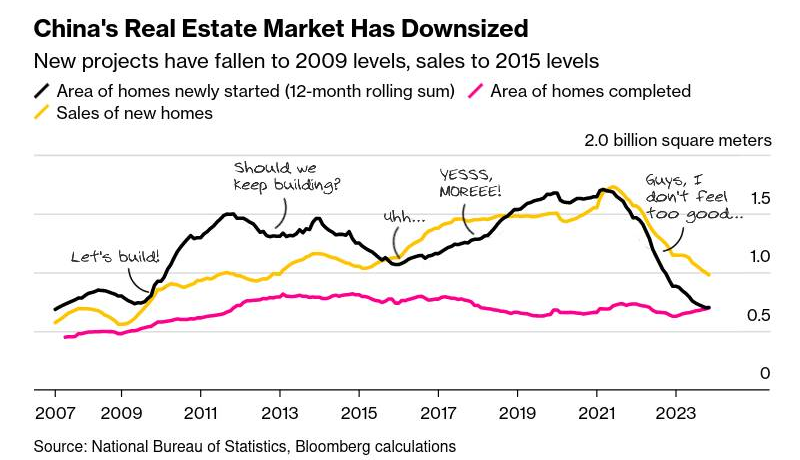

The sector cratered abruptly. With severe financing headwinds hitting the industry, people became afraid of putting down new deposits and down payments for new homes, afraid that developers would not have the money to complete construction. Those that had just done so, on the other hand, were laden with mortgage payments for houses that would never exist – precipitating a nation-wide mortgage boycott.

Chart by Bloomberg (link), defaced by us.

For the first time in years, property prices fell – and they fell relentlessly, for two straight years. Last December, for instance, prices were 20% lower than they were a year ago. Some think they’ll fall another 10% before they plateau. Buyers are now waiting for the industry to bottom out before making purchases, adding to its woes.

In time, it appears, China’s crackdown may cost the country as much as US$ 1.3 trillion. Authorities have back-tracked, to some degree, attempted a slew of measures to stop the bleed.

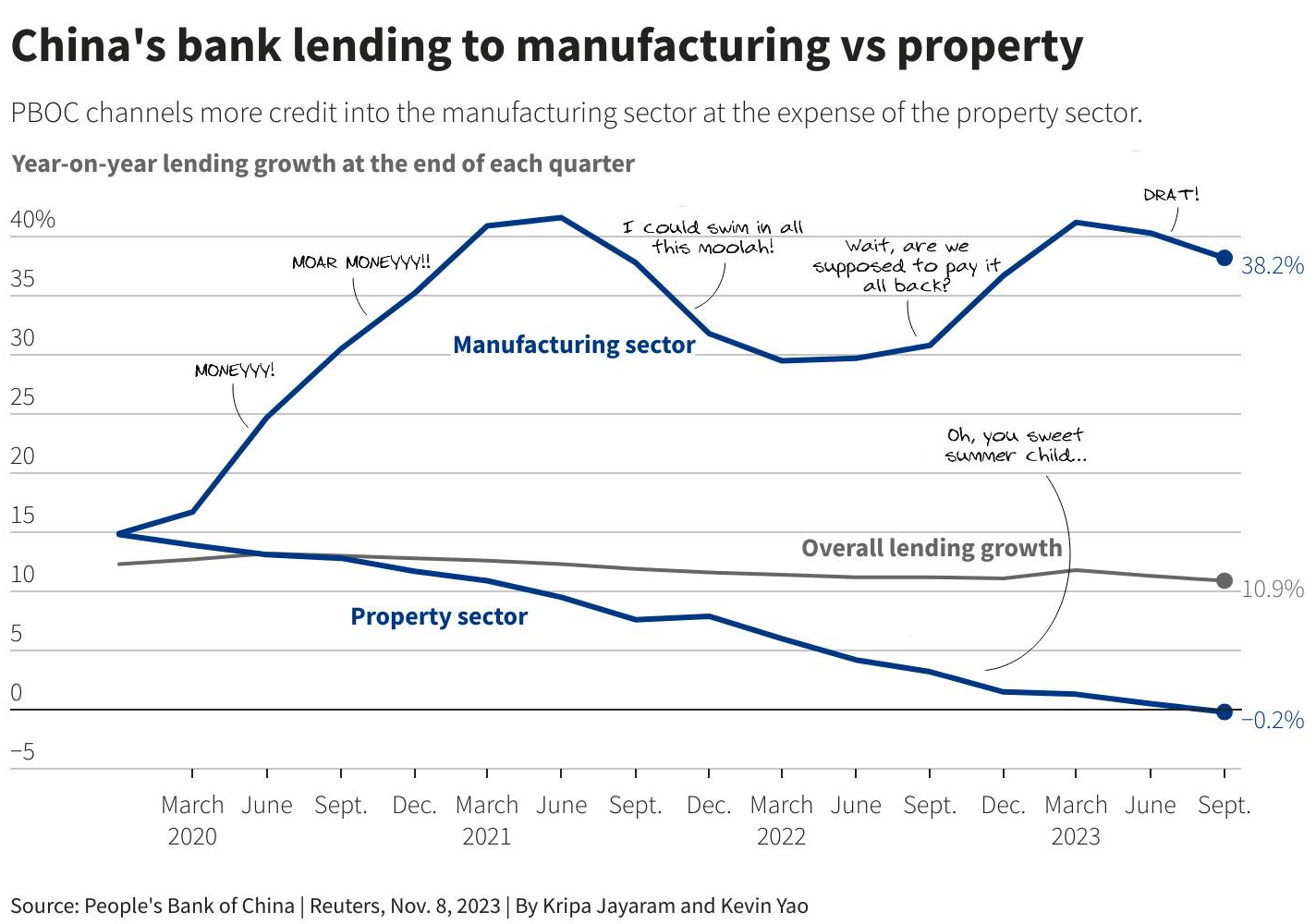

At the same time, however, China is making a larger push to rebalance its economy. Chinese banks have made an abrupt switch, ramping up lending to the country’s manufacturing sector by almost 40%. More recently, the Chinese government announced an allocation of US$ 1.45 billion for schemes to bolster its manufacturing sector. The country is betting on high-end technology – electric vehicles, solar panels, advanced semiconductors and the like – for the next wave of its export-led growth.

Chart by Reuters (link), defaced by us.

This is working, to a degree. Last year, for instance, China emerged as the world’s largest automobile exporter, leaving behind South Korea, Germany and Japan, that have long dominated the industry. Still, the success of an industry is not the same as the success of an entire industrial regime, and the Chinese are as vulnerable to Murphy’s law as the rest of us. Whether these industries can usher a new era of growth remains an open question.

Where do we go now?

Given China’s economic woes, deleveraging and reducing the role of the real estate sector is, at least in broad brush strokes, good advice.

Even so, its measures have caused pain. In one swoop, China hacked through an industry that made for a third of its GDP, and its impact is visible on the country’s economic performance. This, in turn, has created marked uncertainty in the lives of the 24 million people that work in the industry. Housing, moreover, is not only important as an economic product: people’s lives and dreams (and 74% of their savings, on average) are bound in it. When the industry collapsed, housing prices fell, and that has dealt a psychological blow to the average Chinese person.

Is this bitter medicine, though? Or is this a severe economic blunder? Is the Chinese economic miracle over, or are we at the precipice of a new chapter?

The answer to these questions will hinge on several matters. China will have to successfully manage a major economic pivot, fight many political fires in doing so, and over the long-term, learn to empower its own citizens. Through this transition, it will have to brave economic setbacks, endure poor optics and make difficult compromises. It’s a tall order, but one should be wary of betting against a billion and a half people trying to make their lives better.

For the moment, however, there is a wildfire blowing through China.