Investing is a problem that has been solved

“Investing is a problem that has been solved.”

Dave Nadig, a veteran of the US ETF industry, said this on a podcast, and it has been stuck in my head ever since. I remembered this quote because I saw this poll on Twitter (Umm… X. What sort of name is that?). I’ve been thinking and writing about how to get regular people to invest for some time, and I have thoughts. Since I’m on the internet, I must subject you to them—that’s the rule.

So, is investing solved?

In my view, the answer is both yes and no. Is the core problem of saving, investing, and building wealth solved?

Yes.

So, I love these grand challenges. I think they focus the mind. And for a long time, investing was kind of this grand challenge and starting you know, going all the way back to the Fama-French and then all the amazing work that’s been done, you know, Jim Simons. All sorts of people over the years have teased apart what really makes markets work, to remove as much uncertainty from it. And while it is not still a science in the sense that I can tell you precisely what set of inputs is going to reveal what set of results. I feel like it is incredibly well-understood.

And the pieces that we don’t understand that get knocked down in the academic journals once a year are very small. The pieces – people are now talking about scraping five basis points of alpha from better trading strategies. Or timing strategies or you know, arbitraging sub-second price discrepancies and information flows. That’s the deep end of the pool, right? That is fundamentally a solved problem, the way that building a building is a solved problem and we’re just arguing about what you’re putting on the roof.

So, from that perspective, I just don’t think that there’s that much ‘interesting’ left in the core science of how investing works. It doesn’t mean it’s easy. It just means it’s largely solved.

— Dave Nadig.

Let me make this more concrete. Today, building a globally diversified portfolio is inexpensive. Take a look at this hypothetical portfolio of funds along with their expense ratios:

- Zerodha Nifty LargeMidcap 250 Index Fund: 0.25% (shameless plug 🙈)

- Motilal Oswal S&P 500 Index Fund: 0.55%

- Bandhan Bond Fund Short Term Plan: 0.30%

- ICICI Prudential Gold ETF: 0.50%

Disclaimer: These funds are not a recommendation!

If you invest 30% in India, 30% in the US, 30% in debt, and 10% in gold, your blended expense ratio will be just about 0.40%. That’s cheap. It will continue to get cheaper as the funds get bigger. So, the problem of building a globally diversified portfolio is solved. The problem that’s yet to be solved is getting people to think holistically about their personal finances and behave well with their money. In the grand scheme of things, investing is a giant distraction beyond a point. Most people have far bigger personal priorities than investing. I’ll explain them as we go along.

There’s lots of solved problems that are not easy. and the reason I put that out there was because I think the more interesting challenge, the real grand challenge, is human beings and how we interact with money and how we plan for a lifetime. So don’t try to solve that problem. It’s largely solved. You can go get some turnkey asset management program. As an advisor, you could get somebody’s model portfolio, or you could hire some, you know, three CFAs and do it yourself. But it shouldn’t be your primary focus. Your primary focus should be solving the much harder problem, which is actually working with human beings, right? The advice part of being a financial adviser is the hard part. That’s the part where you should earn the money.

— Dave Nadig

Just because investing is solved doesn’t mean it’s easy. Imagine these scenarios:

- You meet a friend who just invested in a monkey coin and makes 500% while your stupid “diversified” mutual funds and “blue chip” stocks are up only 10%.

- You get an unknown message on WhatsApp from a beautiful girl. She likes you and introduces you to a wonderful investment that promises to double your money every month.

- Your uncle, with the authoritative voice of a science professor, tells you that LIC policies are the best investment.

- Your parents ask you what happens if they have health issues. You are shocked and you have no answer because you aren’t prepared.

- There’s a raging bull market, and useless things are going up while your “fundamentally sound” investments look like flat horizontal lines.

- You want to buy a house but have no idea what a loan or interest is.

Fixing your personal finances is easy. Dealing with the insane amount of noise you’ll be bombarded with is difficult. Every time you have to make a decision, you will have to deal with fear, greed, and self-doubt. And if that wasn’t enough, you’ll have to be comfortable looking like a fool, because compared to your sensible investment portfolio, some useless thing will always do better.

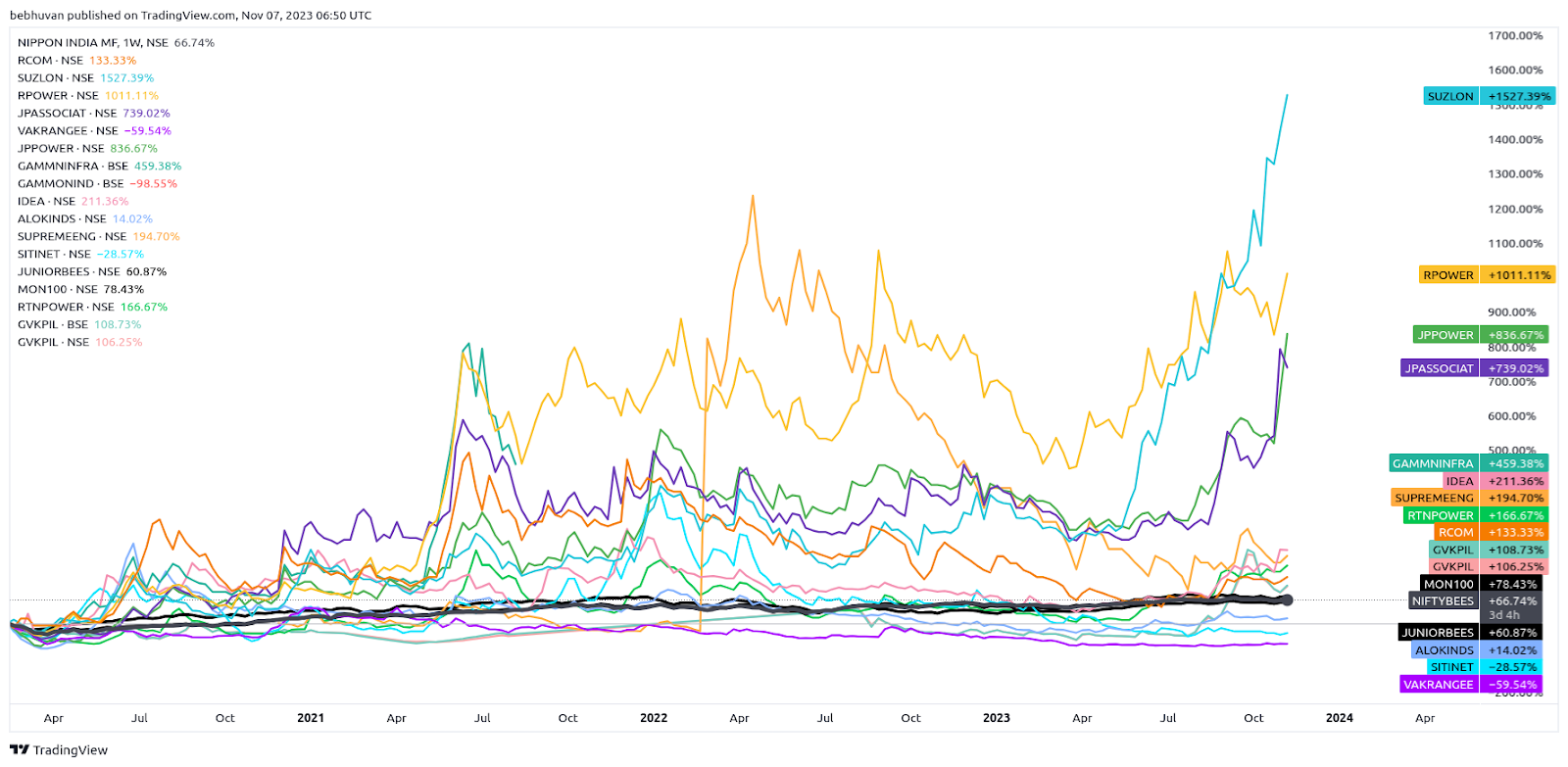

Here’s a dumb thought experiment: if you had picked the worst stocks (penny stocks) at the lows of COVID, you would’ve outperformed Nifty, Warren Buffett, and Rakesh Jhunjunwala (may he rest in peace). Imagine you had a friend who did just this; you’d look like an idiot whenever you discussed your portfolio in the next three years. And there’s a good chance you’ll feel like one, too. This is what makes investing both easy and hard at the same time.

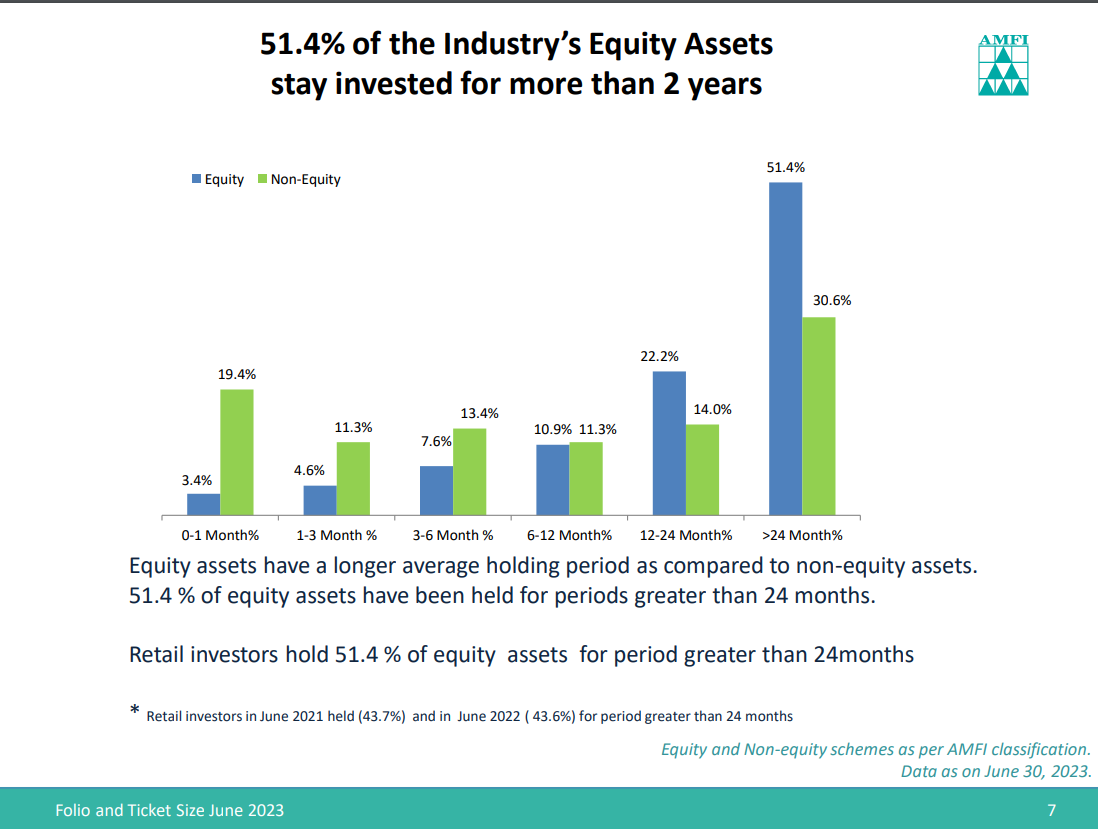

Knowing what to do and doing it are two different things. Modern financial markets are over 400 years old. Everything else in the markets may have changed, but the one thing that hasn’t is human behavior. Investors have and will continue to do stupid things. They’ll do them despite knowing they are wrong. It goes to show that trying to change human behavior is like going against gravity.

All this is just about investing. If something as uncomplicated as investing is this hard, imagine how hard all the other financial decisions you have to make might be.

There are two ways to see this:

- Humans are hopeless creatures that can’t make a good choice to save their lives.

- We are not useless. We just do dumb things sometimes because our brains were not built for the 21st century.

We’re hopeless creatures!

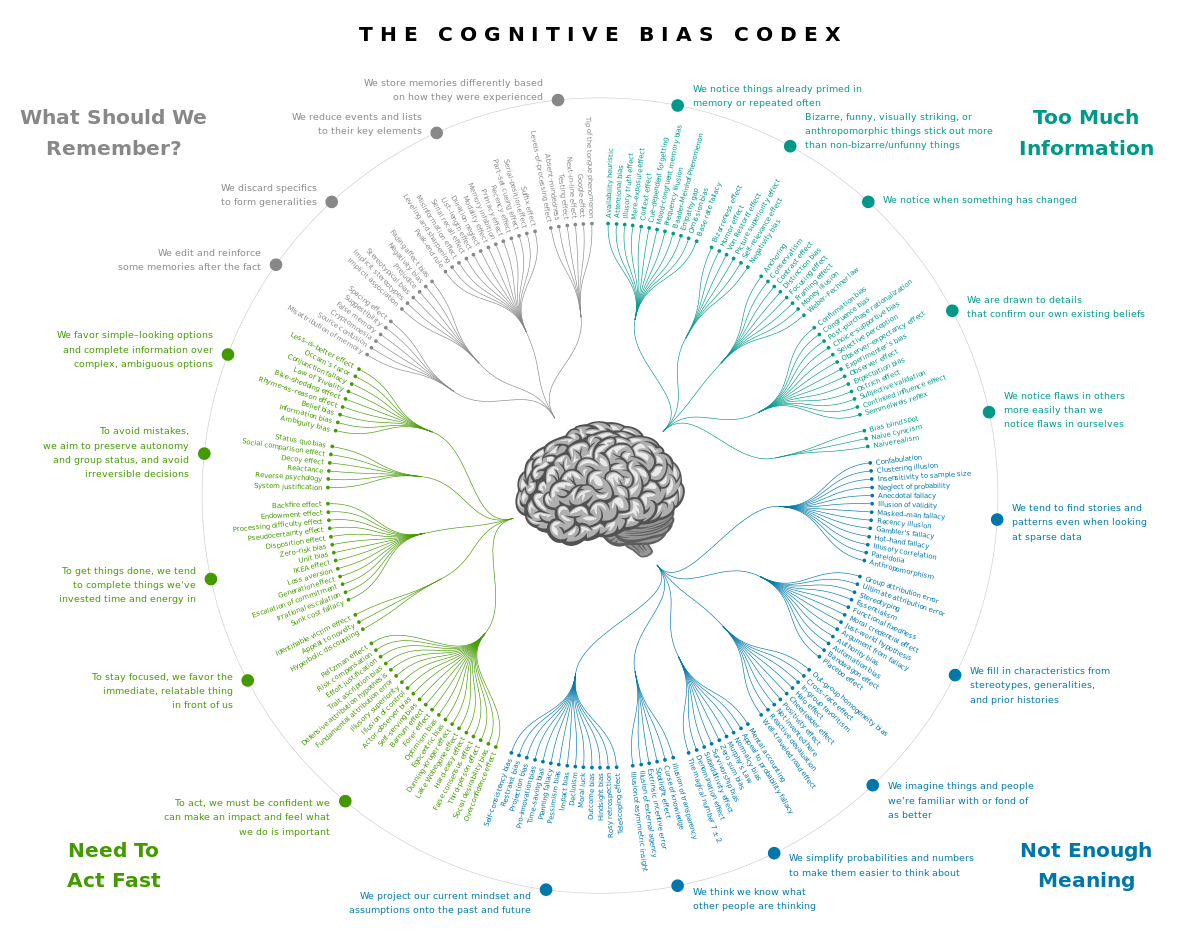

We’re biased: that’s the common answer you’ll hear. Until the 1970s, economists operated under the assumption that people are rational: they consider all available information, assess probabilities, and make rational choices in their self-interest. In 1974, Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman published a seminal paper showing that people don’t always make logical decisions. They showed that people rely on certain “heuristics” or shortcuts when making decisions. While these heuristics work well most of the time, they sometimes lead to systematic errors like availability, representativeness, and anchoring. These errors lead people to make mistakes when judging probabilities and making risk-reward judgments. Here are a few famous experiments:

The most often-cited examples of these fallacies are:

Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.

Which is more probable?

- Linda is a bank teller.

- Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

Tversky and Kahneman argue that most people get this problem wrong because they use a heuristic (an easily calculated) procedure called representativeness to make this kind of judgment: Option 2 seems more “representative” of Linda from the description of her, even though it is clearly mathematically less likely.

The anchoring and adjustment heuristic was first theorized by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman. In one of their first studies, participants were asked to compute, within 5 seconds, the product of the numbers one through to eight, either as 1 × 2 × 3 × 4 × 5 × 6 × 7 × 8 or reversed as 8 × 7 × 6 × 5 × 4 × 3 × 2 × 1. Because participants did not have enough time to calculate the full answer, they had to make an estimate after their first few multiplications. When these first multiplications gave a small answer – because the sequence started with small numbers – the median estimate was 512; when the sequence started with the larger numbers, the median estimate was 2,250. (The correct answer is 40,320.)

Kahneman and Tversky may or may not have assumed people were irrational, but soon this became accepted wisdom in the behavioral sciences. I discovered behavioral finance in 2016. By then, academics had a short list of 300 biases. Soon, the notion that people are irrational led to the belief that people had to be saved from themselves, and nudges became popular.

No, we’re not hopeless

Not everybody agreed that humans were irrational. To call people irrational, you first have to define irrationality. There must be something you compare people to. Behavioral economics exposed the stupidity of assuming god-like rationality. The flaw in behavioral economics, however, was that particular behaviors were still judged as being biased or irrational. Behavioral economists implicitly continued to see certain optimal choices or behaviors as a benchmark. Deviations from this ‘ideal’ way of behaving were considered biased and irrational.

Evolutionary theorists, in contrast, proposed alternative hypotheses about human behavior. They argued that the human brain is the result of millions of years of evolution. If we were so bad at making decisions, we wouldn’t have survived and outlived other hominids for 200,000–300,000 years. Evolutionary theorists argue that our so-called “biases” are context-specific adaptive survival mechanisms. What seems like a bias when compared to perfect behavior becomes a survival mechanism when looked at from an evolutionary lens.

“Reality is a powerful selection pressure. A hominid that soothed itself by believing that a lion was a turtle or that eating sand would nourish its body would be out-reproduced by its reality-based rivals.”

― Steven Pinker

Take ‘risk aversion’. Numerous studies have shown that losses hurt twice as much as gains. This loss-averse behavior looks irrational in isolation, but consider why we inherited it. Our ancestors lived in a hostile environment where death was always around the corner. Imagine seeing a coiled object near a tree. Running away thinking it was a snake cost less than poking it to find out if it was actually a snake and getting bitten. In other words, being risk-averse or not dying was more important than being clear-eyed about reality. So, our brains naturally evolved to be more sensitive to losses than gains.

There’s an evolutionary explanation for our preference for high-calorie foods as well. For much of humanity, food scarcity was the norm, and our brains were energy-hungry compared to other body organs. One hypothesis for why people don’t save and invest is that our ancestors didn’t live long enough, and there was no point in thinking about the future. The biggest priority for our ancestors was survival and reproduction, which meant that being present-biased was a good thing.

It’s not that humans are uniquely irrational. Our so-called biases can be seen in other species as well. In one famous study, researchers simulated an environment where capuchin monkeys had to exchange tokens for food. The monkeys, much like humans, showed ‘irrational’ loss aversion. This leads to an obvious question: If all of our behaviors can be explained by evolution, are we perfect?

Of course not.

Just because evolution can explain our behavior doesn’t mean we’re perfect. Famed and author Robert Sapolsky once said this about the complexity of understanding human behavior:

When a behaviour occurs—whether it’s wonderful, appalling, or ambiguously in-between—we ask the biological question, ‘Why did that behaviour just happen?’ This inquiry encompasses a variety of questions. What happened in the individual’s nervous system one second before that led to that good, bad, or ambiguous behaviour? What were the sensory inputs seconds to minutes earlier that triggered those neural responses? What were the hormone levels hours to days earlier that made the organism more or less sensitive to certain sensory stimuli?

It’s folly to judge human behavior without considering the evolutionary, biological, social, and cultural context. Without understanding the interplay of these factors, all human behavior will seem irrational. One of the most vocal critics of Kahneman’s and Tversky’s heuristics-and-biases approaches is Gerd Gigerenzer, a German psychologist. In reality, though, their views are much closer to each other than they’d care to admit. Gigerenzer argues that modern behavioral economics is based on illogical foundations. Many of our so-called biases are non-existent or rational when considered from an ecological perspective. That is, these behaviors are adaptive mechanisms that humans evolved over millions of years.

For example, behavioral economics suggests that people are bad at assessing probabilities. Gigerenzer and others argue that historically, humans never had to calculate probabilities in the cold and clinical manner required today. The notion of a ‘50% chance of a coin landing on heads’ feels foreign to our minds—so distant from our evolutionary adaptations that it often eludes our grasp. However, if the same concept is presented in terms of naturally occurring frequencies, such as ‘a coin lands on heads 5 out of 10 times,’ the cognitive bias disappears.

Gigerenzer’s biggest contribution is salvaging the reputation of heuristics. While Kahneman and Tversky argued that heuristics may lead people to make errors, Gigerenzer argues the opposite. Gigerenzer distinguishes situations of risk from situations of uncertainty. In a risky situation, like roulette, for example, it’s possible to figure out all possible alternatives, calculate probabilities, and make the optimal choice. Even in simple everyday situations, it’s impossible to do this. Would you choose to wear a sweater today by mapping every single weather event possible and tabulating their respective probabilities? Of course not. At most, you might Google the day’s weather forecast. In the real world, most situations we deal with are not risky but uncertain. In uncertain situations, it’s impossible to figure out all the alternatives and probabilities.

According to Gigerenzer, in situations of uncertainty, the rational thing is not to build complex models but to do the opposite. He advocates for the use of heuristics, or simple-and-fast rules, to make quick decisions. You might decide not to wear a sweater today, for instance, because you generally don’t wear a sweater in late February. It’s that easy. There’s no need for a fancier model. Such rules are ideal for making decisions in situations of uncertainty. The goal of heuristics isn’t to make optimal decisions, because those can only be known in hindsight.

To demonstrate the usefulness of heuristics, Gigerenzer gives the example of how a player catches a ball. When a fielder has to catch a ball, they don’t need to make complex calculations involving Newtonian physics or differential equations. They just have to fix their gaze on the ball and run in such a way that their gaze remains constant. This is an example of a ‘gaze heuristic’. Gigerenzer has demonstrated the utility of other heuristics, such as:

- Take the best heuristic: When deciding between two alternatives, you make a choice based on just one important characteristic.

- The 1/n heuristic: When choosing to allocate between different asset classes, in the absence of an optimized model, equal-weighting is a reasonable approach (there are caveats to this, of course).

I’m confused. Are we rational or irrational?

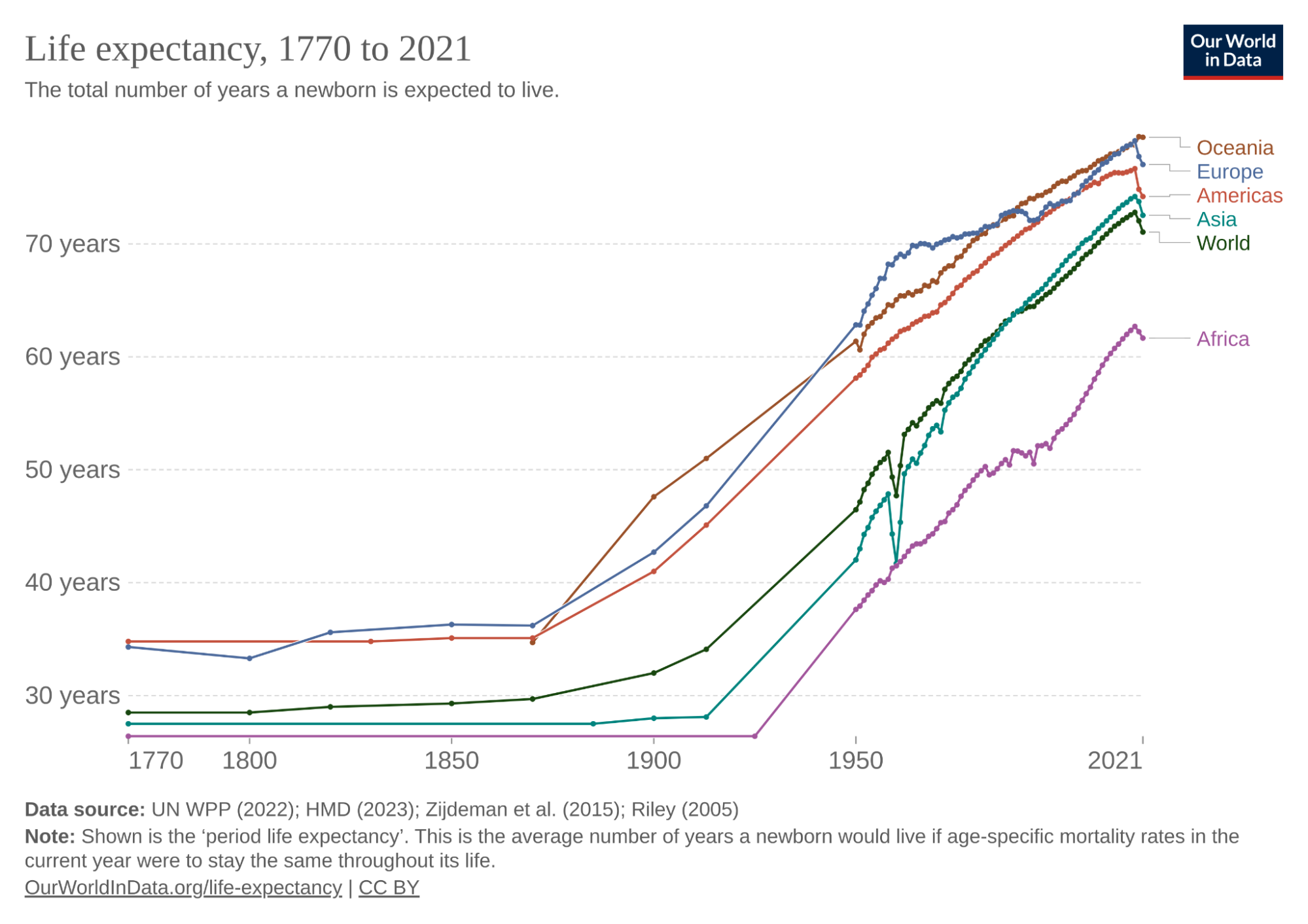

When measured against pure logic, we all look biased, but that’s unfair. As some researchers put it, we’re facing the complexity of the 21st century with a stone-age brain. The world, even a few thousand years ago, was harsh. Most of us didn’t live long enough to think long-term. The average global life expectancy was 30 years in the 1990s, and it’s more than doubled to 70 years today.

William Bernstein, who’s written best-selling books on finance and history, once said, “Human nature turns out to be a virtual petri dish of financially pathologic behavior.” I disagree with him. It’s not that we are pathetic creatures. We just need different tools. Even evolutionary thinkers agree that not all of our evolved traits are helpful in the 21st century.

Sometimes you find yourself in an environment where your brain and your body have evolved for a past environment, but you’re now currently in a new one. Us for example, we evolved in a very different environment than we live in today. And so we now sometimes experience an evolutionary mismatch between the environment that we evolved in and the environment that we inhabit today. And so that leads to some maladaptive outcomes. And then there are several other constraints on natural selection, but there’s actually even more interesting things to be said here I think. One of them is that sometimes mechanisms evolve and they produce errors as part of their design.

What are these ‘different tools’, though?

Similar to the heuristics I mentioned above, we’ll have to use simple rules that can help us accomplish our goals. There are no perfect solutions, and it’s important that when it comes to personal finance, you don’t let perfect be the enemy of good. Before you get down to making decisions, understand the holistic nature of personal finance and the importance of “personal” over “finance.” So, to be clear, none of us are stupid. The next time someone calls you biased, feel free to punch them by accident.

A few things you should know:

-

- Understand that your future earning potential is your biggest asset. When you are young, you should spend as much time making yourself as valuable as you can. The return on your human capital (future earning potential) will be far higher than your investments.

- Money is the single biggest source of stress for people. A lot of financial anxiety is the result of poor spending habits and terrible beliefs about money. Having a good relationship with money is critical.

- Basic financial literacy is a life skill in the 21st century. Just having basic knowledge of savings, spending, borrowing, and investing can help you get rich slowly.

- Money is important, but it’s not the only important thing in life. Think about your personal finances in a holistic way. Your physical health, mental health, and good relationships are far more important.

- You cannot deal with your insecurities by spending money.

- Spending is a skill, just like saving.

- You can have anything, but not everything. Everything in life is a trade-off. Choose what’s important.

- Having good personal finances means looking at the big picture and thinking about others in your life as well. Think about how your personal financial decisions affect others, like your parents and partners. For example, if you don’t have adequate life insurance, what does this mean for your loved ones?

- Everything, from saving to investing to insurance, can be as simple or complex as possible. Simple doesn’t mean bad—the choice is yours. If you choose simple, here’s how to take care of your personal finances.

- The mostly iron law of finance is that activity and results are inversely proportional. The more you tinker, the lower your return will be.

- You can’t put a number on everything. The peace of mind you get from knowing that you have adequate insurance, savings, and investments is priceless.

Now I understand that these are not tools in the strictest sense of the word. In upcoming articles, I will write about specific tools and hacks that you can use to manage your personal finances.

Man, what an in depth article! love reading! Keep`em coming! Also appreciate your efforts to distill all the thoughts into a power packed blog 🙂

too big an article, sirji