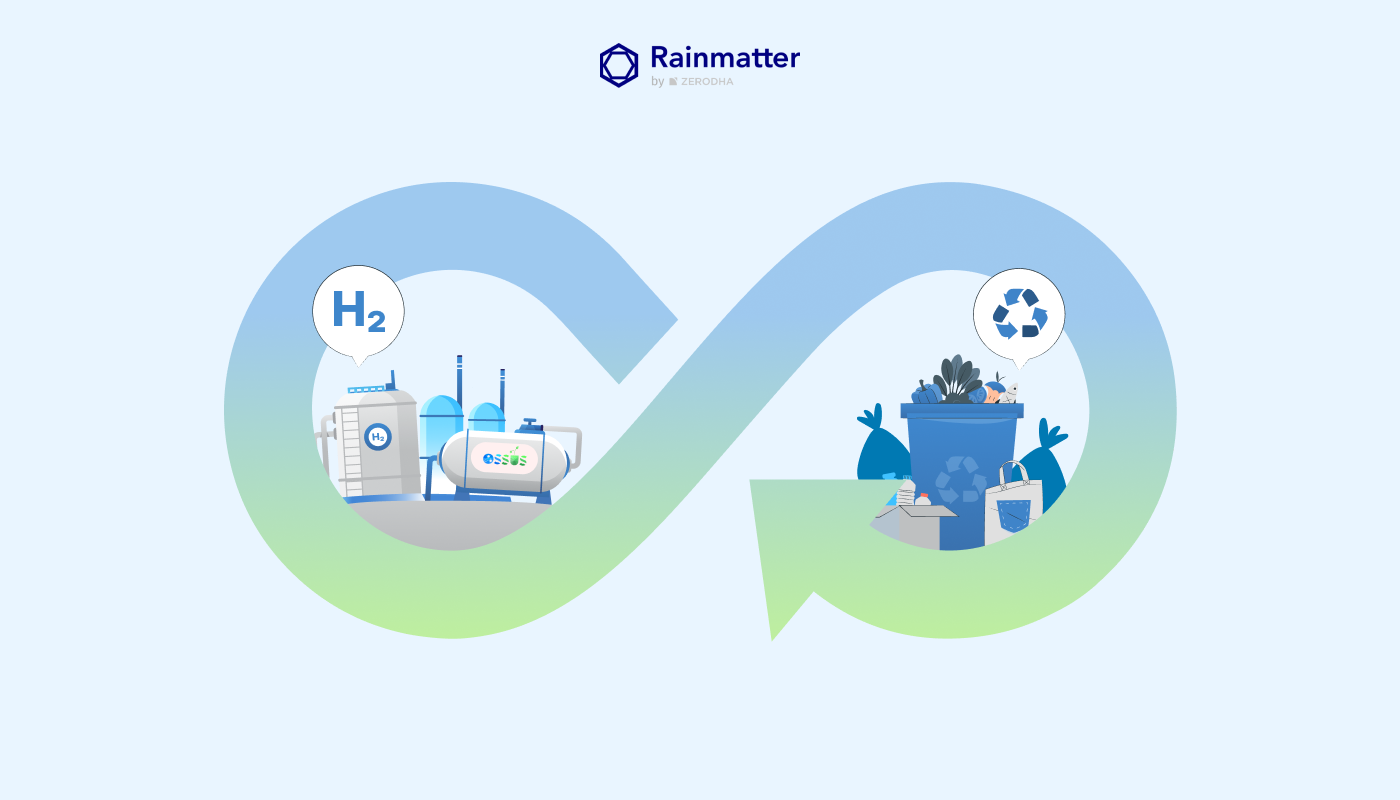

Ossus: Green hydrogen from first principles

Hydrogen has been hailed as a possible solution to the world’s energy needs for a hundred years. While its role as a fuel is still being debated, hydrogen is also a key ingredient in a range of industrial processes such as petroleum refining, manufacturing ammonia for fertilisers, methanol production, treatment and production of metals. India’s industrial processes use about 5 million metric tonnes per annum (MMTPA), most of which is produced using an age-old process called steam reforming of natural gas and naphtha. Basically from fossil fuels.

Defining green hydrogen became political

The world figured out a better way: by splitting water in an electrolyser. The problem is that this process uses too much energy. Hence, the focus on renewable energy like solar and wind to make ‘green hydrogen’. Europe had some additional factors in the green hydrogen definition –

- Being generated by dedicated new renewable energy capacity (additionality),

- Is in the same location as hydrogen production (deliverability), and

- Ensuring temporal alignment between renewable electricity generation and hydrogen production (temporal matching).

(source: JMK Research’s March 2024 paper titled India’s $2.1b leap towards Green Hydrogen page 23).

India’s definitions –

https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1950421

The regulation disparities hinder global comparisons of Indian projects and affect market access (exports) for Indian hydrogen not meeting these criteria.

The definitions highlighted the difficulties with adopting green hydrogen separate from the cost factor. These include the transmission and infrastructure. India’s National Green Hydrogen Mission (NGHM) aims to solve for some of these with a budget of US$2.4 billion. However, Indian players had yet to start production of any green hydrogen.

Bio-renewables have potential

In 2016, a young PhD student, Suruchi Rao was working on generating methane from organic waste. She teamed up with Kamar Basha to develop a process by which bio-organisms generate electricity. The duo applied for and received a bunch of grants to develop their idea. Eventually they patented their process and set up a start-up with initial funding from Shell.

The breakthrough innovation allows the world to think about green hydrogen in a different way rather than just focusing on splitting water. The advantages are many – from a cost that’s less than half to avoiding the transmission issue.

Like Ossus, there are many other startups around the world that are working on similar innovation such that the definitions are being broadened.

Watch the latest episode of The Climate Conversations.

Evolving business model

Ossus’ alternative model to generating hydrogen was significantly cheaper, on-site, and cleaned up the effluent water as a by-product. It was received well by some big names such as Tata Steel and ONGC which have set up the Ossus bio-reactors at their sites. Ossus decided to focus on the ‘hard to abate’ industries – oil refineries, petrochemicals and steel production.

At this stage, Ossus met Nikhil Kamath who eventually invested in the company through Gruhas. Rainmatter also invested. Shell remains a small shareholder.

As Suruchi explained the episode, Ossus’ business model has evolved after raising capital: the company was putting in the capex to charge for the hydrogen, but it’s now considering allowing the client to pay for their own capex and paying a lower price for the hydrogen.

The company’s third co-founder focuses on the patent strategy as the company has ambitions to produce 10 percent of India’s target by itself in the next year. Rao predicts revenue to cross 2500 crores next year and a billion dollars in the next few.

Exactly what India needs. Young founders with breakthrough ideas and lofty ambitions.