Organic Mandya | An experiment in improving health and livelihoods

More Indians than ever are experiencing health issues. More Indians than ever are giving up farming because of the low incomes it provides, and are migrating to cities to do menial labour. These might seem like unrelated issues. One engineer, however, saw a common cause for these symptoms — farming practices that encourage mono-cropping grains, with expensive foreign seeds, subsidised fertilisers and pesticides, and free electricity. The solution, to him, could be organic or natural farming. But this had to be proven.

Modeling a sustainable farm

Madhu Chandan was up for the challenge. After training as an engineer in Mysore and working in the US, he had started a product company. He convinced his family to move from the US back to Mandya in 2014, to start his own one-acre model organic farm in 2015.

In this episode of the climate conversations, we went to Mandya to chat with Madhu about what he sees as the problem, and potential solutions.

Madhu began with a ‘fruit-and-vegetable model,’ planting more than 650 varieties over the two years he lived there. Realising that the fruit trees take years to bear fruit, and hence income, he then evolved his model to a ‘vegetables-and-greens’ one, which can start generating income sooner. At the heart of his farm is a pair of cows that not only provides milk, but more importantly, the dung and urine which goes into the making of organic fertilisers. The farm looked natural, with neatly organised rows of vegetables. Madhu pointed to a natural solutions for pests — flowers and pomegranates.

A combination of multi-cropping and organic fertilisers ensures the soil quality improves over time and needs very little water. This is in stark contrast to the mono-crop farms, which are fed with copious amounts of chemical fertiliser and pesticides, washed down with precious water, according to Madhu.

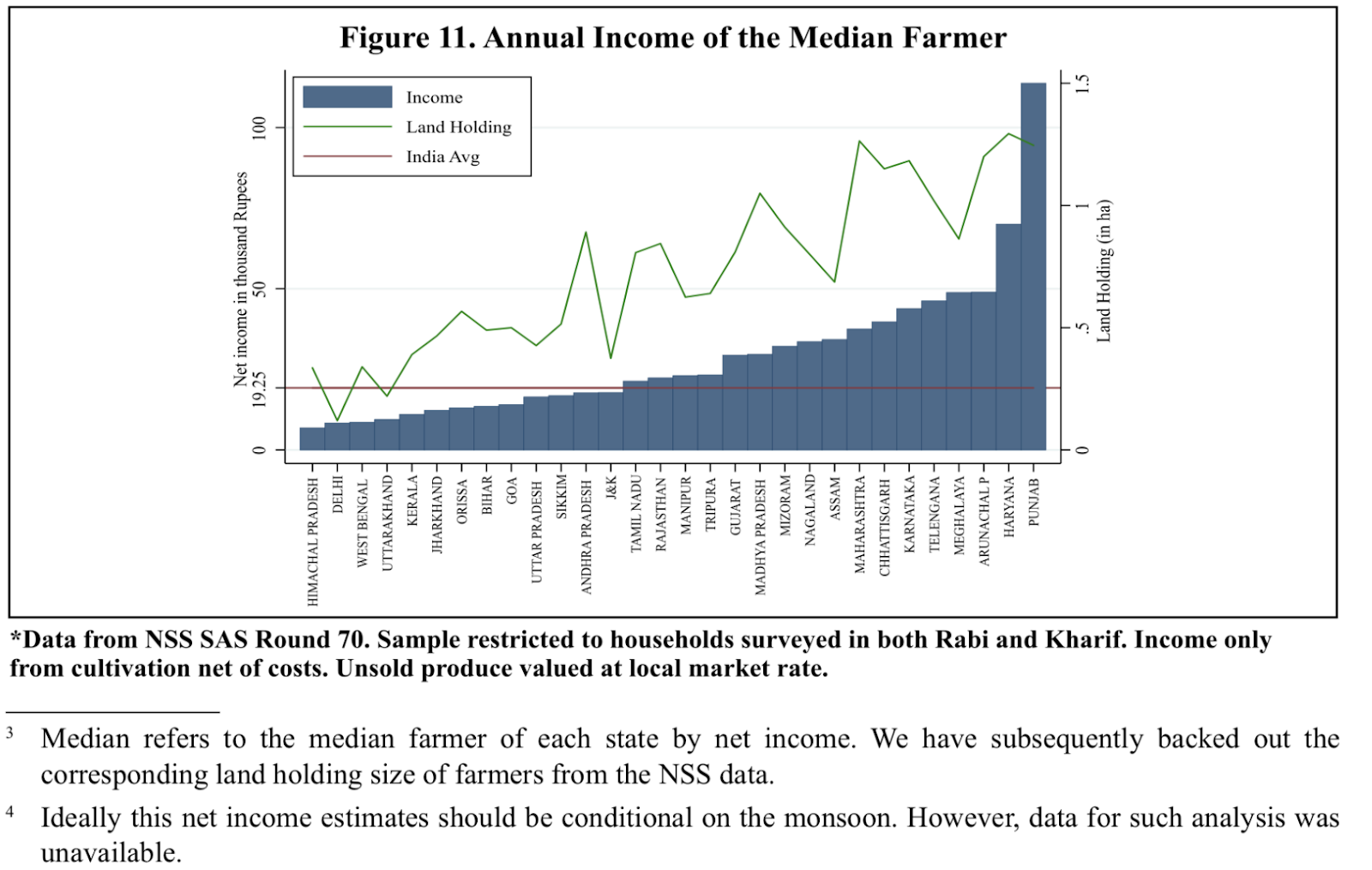

The green revolution needs an update. Even the Indian government budget has highlighted disquieting trends — lack of exit, land and water issues etc. It also highlights the issue of low farmer incomes, showing the disparity across states.

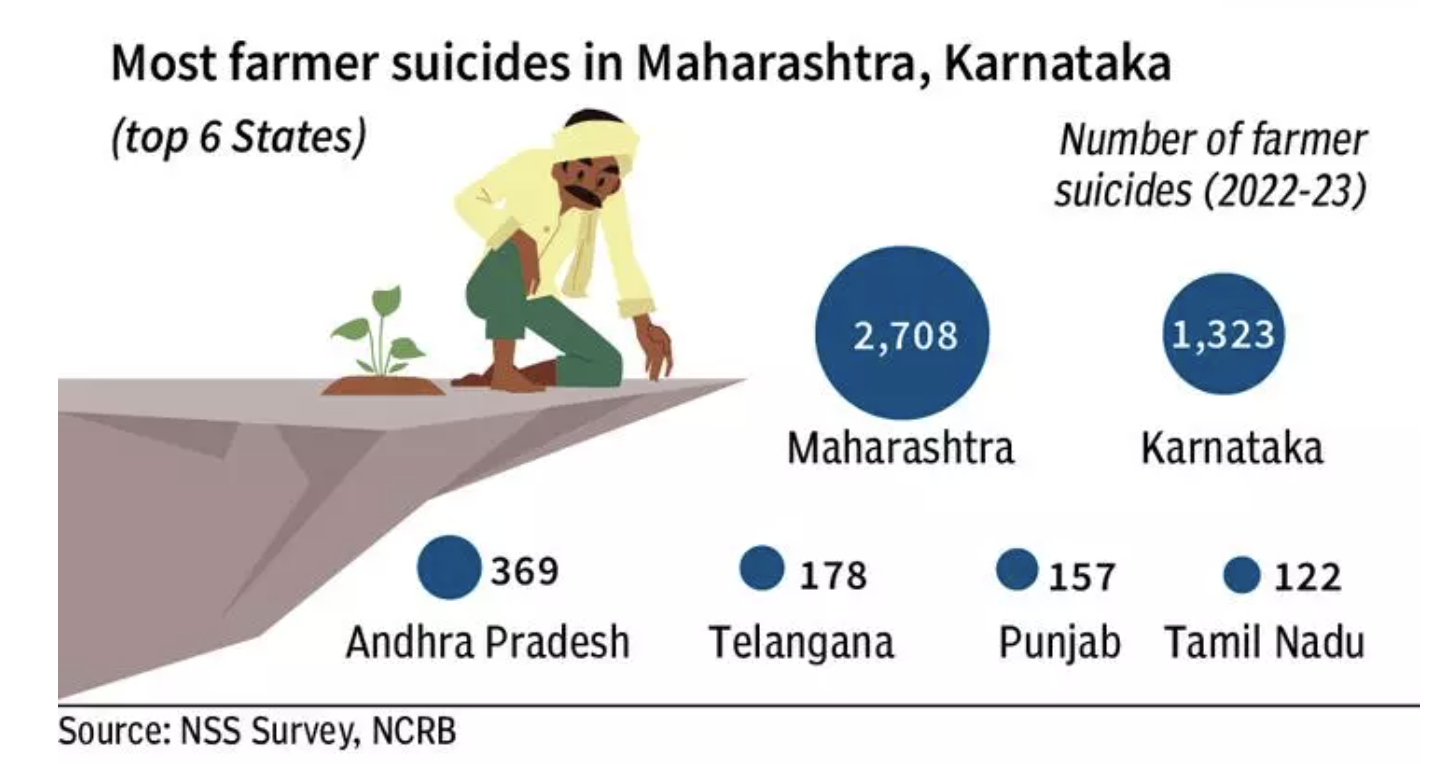

The low incomes, combined with heavy debt, lead desperate people to commit suicide.

The low income and loss of life was, to Madhu, the most distressing issue, and he wanted to address it as urgently as possible. His models lead to farmers’ earnings increasing progressively to more than Rs. 1 lakh a month.

FPOs help with awareness and economies of scale

After settling on the organic model, Madhu started showing it to farmers around the state, conducting free workshops. The farmers didn’t need a lot of convincing. Madhu started an impromptu group, and inspired by his riveting talks every Monday, more and more farmers joined the group. Eventually, it led to the formation of a Farmer Producer Organisation — Mandya Organic Farmers Co-operative Society.

There are now:

- 12,000+ farmers under the Co-Op Society

- 7,000+ farmers in 300+ Organic Farmers Clubs spread across 270 Villages

- 4,500 women members (Farmers-cum-Micro-Entrepreneurs) across 200 Villages

Mandya Organic Farmers Co-operative Society undertakes a number of initiatives like free training programs, organises farmer markets, donates cows to marginal farmers, rejuvenates lakes, plants saplings, and more.

Building a processing and marketing organization

The next challenge was convincing farmers that their perishable organic produce could fetch high enough prices. This was pretty crucial, as improving farmer livelihood was one of the main reasons for this grand experiment (apart from the health benefits of reducing chemicals in our food system).

Organic Mandya was actually formed as a marketing wing to support the Mandya Organic Farmers Co-Operative Society.

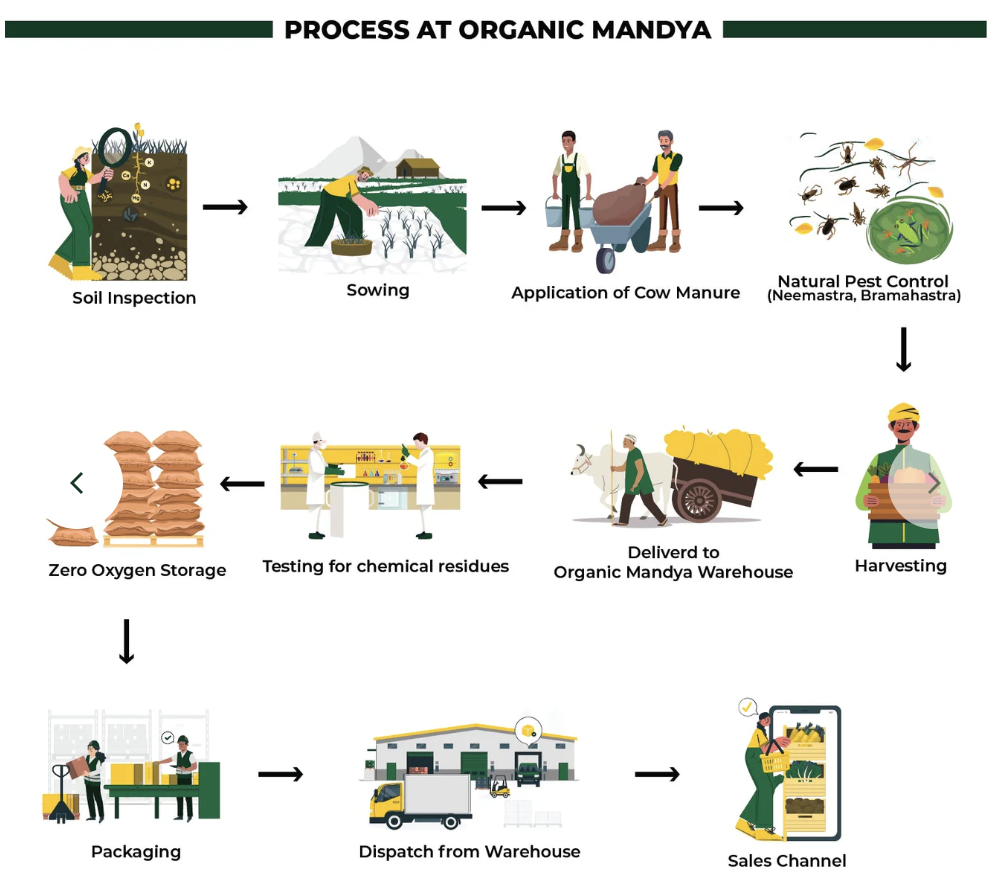

The company raised about 14 crores (~ USD 1.8 million) capital from Rainmatter to build a collection and processing unit. As the video shows, the unit cleans and packs the produce. It also has a dairy unit that pasteurises and packs milk, apart from turning it into curd, butter/ghee and paneer. The buttermilk is donated to the needy.

The company’s first physical store on the highway started on a disastrous note, but then recovered. There are now nine stores around Bengaluru. Customers can also buy through an online store. There is even a prime-like membership scheme, which offers a 30% discount in exchange for a nominal membership fee.

Can it scale?

Organic farmer markets seem to cater to the well-off. The question is whether they can be scaled enough to not only ensure the country’s food security but also increase farmer incomes.

Madhu believes it’s his job to set the example, but it’s the government’s job to make it into policy.

The example has been set. Recognizing his achievements in Agriculture, the Central Government nominated him as a Management Committee Member of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR). Harvard Business School has a case study on Organic Mandya.

Madhu tried to influence government policy by standing for the local elections himself. He didn’t succeed, but is still optimistic that consumer demand will lead to policy action soon.

We hope so too.