Risk profiling | A key part of personal finance that few understand

Personal finance content tends to focus on ‘investment risks’. Inflation risk: that your money will not keep its purchasing power. Interest rate risk: that your loan repayments can increase while the value of your portfolio decreases at the same time. Market risk: that your portfolio’s current valuation can free-fall because some random oil squabble affects the market mood.

These are all external factors that you need to know, analyse and work around. Inflation, interest rates and markets will always fluctuate; a good financial plan takes these into account. But once market risks are handled, it’s how you react to them that matters.

The biggest risk to a good financial plan is you.

Kind of like life. Even if you’re talented and hard-working, things will suck more than once in your lifetime. It’s how you react to these times that matters.

Obviously, the financial services industry knows this. So it tries to make a ‘risk profile’ on you. This is important enough that regulators mandate it for pretty much every investment transaction — whether you go to a full-fledged professional investment adviser, a limited-scope mutual fund distributor, a fintech platform or even directly approach a financial product provider.

The problem, however, is that different organisations might measure slightly different things, or just measure the same thing badly. Your experience could be very different from place-to-place, and from time-to-time. More importantly, your risk profile may not do what it’s supposed to.

So, what is risk profiling supposed to do?

As I’ve also done in my Money Mindful basics series, let’s dissect this crucial aspect of personal finance and the financial planning process.

What’s a risk profile?

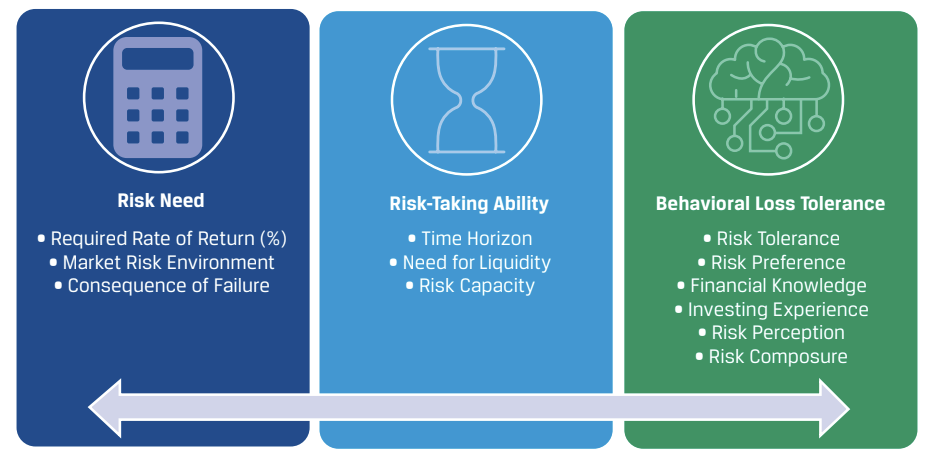

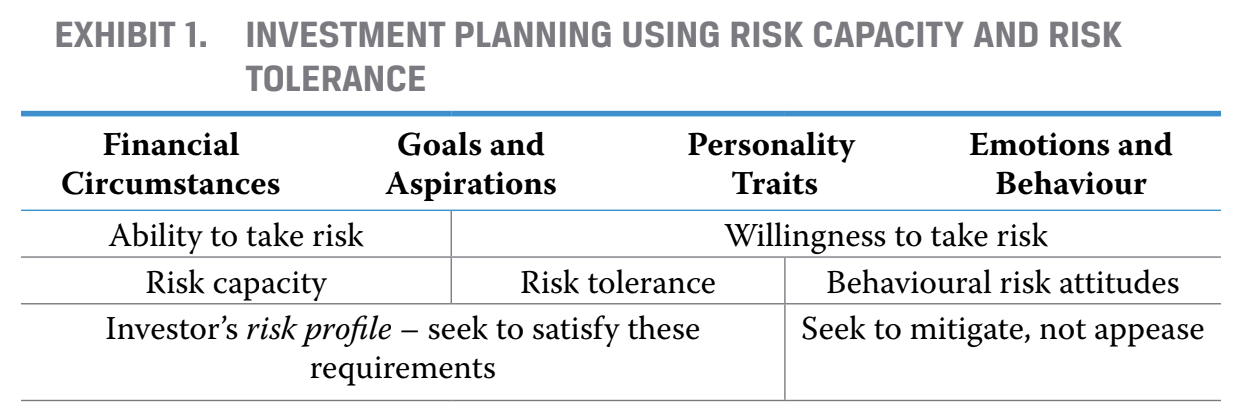

After decades of arguing about terminology, the industry now broadly agrees that the term ‘risk profile’ encompasses three distinct aspects:

- The need to take risk, which is calculated based on the gap between where you are (in terms of finances) and where you want to go (i.e. your goals). This calculation of a ‘required rate of return’ is sometimes separated out completely from your risk profile, as it’s part of the goal-setting or financial planning process anyway.

- The ability or capacity to take risk, which is based on factors such as time horizon and liquidity, which are also fairly objective.

- The willingness to take risk, (also called ‘risk tolerance’ or ‘appetite’) which is a psychological aspect that tries to measure how willing you are to take risks or how much uncertainty you can tolerate in pursuit of your goal. These are personality traits, and are hence apparently quite stable over time.

You can go deeper into each of these:

On top of this, we’re all human. We have shorter-term ‘behavioural biases,’ such as emotional ups and downs, as well as ‘cognitive biases’.

Ideally, a financial adviser must know all three aspects of one’s risk profile before recommending a course of action.

How risk profiling is done

In health or medicine, one can do pathology tests and take X-rays to see inside you. Unfortunately, we can’t yet look inside you to find the risks you should be comfortable with. So, the finance industry simply asks you questions.

While these ‘risk profiling’ questionnaires of different organisations look similar from afar, they are not. They differ widely based on what and how they measure. At one extreme, old-fashioned practitioners believe that risk profiling, as a whole, is hard to do objectively; it’s best done through a subjective, maybe structured, discussion between an investor and their adviser.

At the other end are those who try to measure your risk tolerance objectively using a ‘psychometric’ test, since it’s supposedly a personality trait. A psychometric study combines psychology and measurement. Such practitioners may or may not use another questionnaire to assess your risk capacity.

And then there’s the rest of the world, which uses questionnaires with just 5-6 questions. These claim to be based on finding ‘revealed preferences,’ but mostly have no underlying philosophy of what they are trying to measure. They try to categorise you on a 5-point scale from ‘ultra-conservative’ to ‘ultra-aggressive’, and then try to match you to their own product offerings. There are practical issues with these tests:

- Ideally, a risk profile should include questions about at least two separate aspects (capacity and tolerance). In practice, I have seen questionnaires that mix up questions on both of these, alongside the need to take risk.

- They aren’t based on any evidence on how we can know how one will behave in the future.

- They are worded ambiguously (i.e. badly).

- They simply average the scores from very different questions rather than resolving inconsistencies (for instance, someone having low capacity and high tolerance, or vice versa, may simply be assigned a ‘moderate’ risk profile).

- They don’t follow a standardised scale when presenting results.

The result is that an investor can get very different ‘classification labels’ of ‘conservative’, ‘balanced’ or ‘growth’ from different tests. As a result, they get different recommendations for asset allocation from different firms. We don’t really know where the differences came from. While in developed markets like Australia, the labels carry risk/return expectations so investors can get somewhat comfortable with (or ask more questions about) what they are getting into, this is not the case in India.

Goal-based financial planning processes should ideally assign different risk profiles to different goal buckets. In practice, however, investors are given a single risk profile, with no explanation of how it aligns with different time and liquidity constraints.

A philosophical dilemma

I have been sceptical about risk profiling questionnaires my whole career. I struggle to understand their underlying philosophy, and I’ve always refused to be responsible for them. I’ve never trusted them to actually deliver on their promise of predicting behaviour — especially panic.

Recently, when I spoke with Professor Terrance Odean of UC Berkeley, I asked him for his views on risk profiling. He quipped: “How do you know they have a lower risk profile? Because they take less risk.”

Here’s what he had to say on the topic:

Professor Odean teaches personal finance. And he’s of the view that objective calculations of one’s need and capacity for risk, combined with some subjective assessment of their financial comfort (which comes from knowledge and experience) should be enough for an asset allocation recommendation.

Yes, investors may panic. But that’s what the financial industry generally, and the financial advice industry specifically, is there for: to educate, to guide, to coach. Shouldn’t we put more effort into educating investors to invest better, and training advisers to coach better?

Conclusion

Risk profiling includes at least two distinct aspects – risk capacity and risk tolerance (ignoring the need for risk, which should be considered separately anyway). Capacity is a function of your financial situation while tolerance is supposedly a psychological personality trait. Beyond this, our investing decisions are hit by other shorter term challenges — both emotional and cognitive — that we all suffer from. These aren’t addressed in profiling exercises, though they should.

Whenever you interact with the financial industry, pay attention to the risk profile questionnaire. Ask them the philosophy behind their questions — what they are trying to measure, whether they’re using a well-regarded external tool or if they’ve developed this questionnaire internally, what research supports it, how they use the results, how they map the result with their asset allocation recommendations etc..

After all, the whole point of the risk-profiling exercise is to reduce anxiety for you. If it’s not doing that, let’s keep asking questions.

In the meantime, you should discuss with your adviser how much of a coach you want him or her to be. The onus should be on their skill — not a questionnaire.